Royal Studios and the Creation of the Hi Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

Jeff Dewbray Music Artists Covered

JEFF DEWBRAY MUSIC ARTISTS COVERED Al Green Frank Sinatra Paul McCartney B52's Florida Georgia Line Police Bachman-Turner Overdrive Frankie Vallie Rare Earth Backstreet Boys Garth Brooks Rascal Flatts Barry Manilow Georgia Satellites Rascals Beatles Gin Blossoms Ray Charles Ben E. King Grand Funk Railroad Rick James Big & Rich Honeydrippers Rick Springfield Bill Withers Hootie and the Blowfish Robert Palmer Billy Idol INXS Sam & Dave Billy Joel J Geils Band Sam Cooke Billy Ocean James Taylor Santana Billy Paul Jason Mraz Simple Minds Billy Ray Cyrus Jerry Lee Lewis Sir Mix-a-Lot Black Crowes Jim Croce Smash Mouth Blake Shelton Jimmy Buffet Soft Cell Blues Brothers Joe Cocker Spin Doctors Bob Marley John Legend Steely Dan Bob Seger John Mellencamp Steppenwolf Bobby Brown Johnny Mathis Stevie Wonder Bobby Darin KC & The Sunshine Band Stone Temple Pilots Bobby McFerrin Kenny Loggins Sugarloaf Brain Setzer Kings of Lean The Box Tops Brooks & Dunn Kool and the Gang The Cure Bruce Springsteen Lenny Kravitz The Four Seasons Bruno Mars Lionel Ritchie The Grass Roots Bryan Adams Loggins & Messina The Human League Buster Poindexter Looking Glass The Isley Brothers Cheap Trick Lou Bega The Kingsmen Chuck Berry Louis Armstrong The Knack Commodores Luke Bryan The Righteous Brothers Contours Lynyrd Skynyrd The Rolling Stones Counting Crows Mambo Kings The Spinners Darius Rucker Manfred Mann The Temptations David Lee Roth Maroon 5 The Trammps Dean Martin Marvin Gaye Tom Cochrane Dishwalla Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Tom Jones Dobie Gray Modern English Tom Petty Don McClean Monkees Tommy Tutone Duran Duran Nat King Cole Train Earth Wind & Fire Neil Diamond UB40 Eddie Floyd Nine Days Van Halen Elton John NSYNC Van Morrison Elton John w/Kiki Dee Otis Redding Village People Elvis Presley OutKast Walk The Moon. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Gender on the Billboard Hot Country Songs Chart, 1996-2016

Watson. Manuscript. Gender on the Billboard Hot Country Songs Chart, 1996-2016 Jada Watson (University of Ottawa) [email protected] In May 2015 radio consultant Keith Hill revealed that country radio programmers have strict rules on how many female artists can be included in airplay rotation. Referring to females as the “tomatoes” of the country salad, Hill’s remarks have sparked debate about gender-representation in country music. This paper examines gender-related trends on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart between 1996 and 2016, aiming to investigate how female artists have performed on the charts over this two-decade period. Analyzing long-term trends in frequency distribution, this study uses statistical results to unpack assertions made about women’s marginal status in country music. Keywords: country music; gender; Billboard charts; radio Introduction: #TomatoGate In a 26 May 2015 interview with Russ Penuell of Country AirCheck on the subject of country radio scheduling and ratings, consultant Keith Hill spoke candidly about how female artists factor into the format’s airplay rotation: If you want to make ratings in Country radio, take females out. The reason is mainstream Country radio generates more quarter hours from female listeners at a rate of 70 to 75%, and women like male artists. I’m basing that not only on music tests from over the years, but more than 300 client radio stations. The expectation is we’re principally a male format with a smaller female component. I’ve got about 40 music databases in front of me and the percentage of females in the one with the most is 19%. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Sam Phillips: Producing the Sounds of a Changing South Overview

SAM PHILLIPS: PRODUCING THE SOUNDS OF A CHANGING SOUTH OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How did the recordings Sam Phillips produced at Sun Records, including Elvis Presley’s early work, reflect trends of urbanization and integration in the 1950s American South? OVERVIEW As the U.S. recording industry grew in the first half of the 20th century, so too did the roles of those involved in producing recordings. A “producer” became one or more of many things: talent scout, studio owner, record label owner, repertoire selector, sound engineer, arranger, coach and more. Throughout the 1950s, producer Sam Phillips embodied several of these roles, choosing which artists to record at his Memphis studio and often helping select the material they would play. Phillips released some of the recordings on his Sun Records label, and sold other recordings to labels such as Chess in Chicago. Though Memphis was segregated in the 1950s, Phillips’ studio was not. He was enamored with black music and, as he states in Soundbreaking Episode One, wished to work specifically with black musicians. Phillips attributed his attitude, which was progressive for the time, to his parents’ strong feelings about the need for racial equality and the years he spent working alongside African Americans at a North Alabama farm. Phillips quickly established his studio as a hub of Southern African-American Blues, recording and producing albums for artists such as Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King and releasing what many consider the first ever Rock and Roll single, “Rocket 88” by Jackie Breston and His Delta Cats. But Phillips was aware of the obstacles African-American artists of the 1950’s faced; regardless of his enthusiasm for their music, he knew those recordings would likely never “crossover” and be heard or bought by most white listeners. -

A Period of Rapid Evolution in Bass Playing and Its Effect on Music Through the Lens of Memphis, TN

A period of rapid evolution in bass playing and its effect on music through the lens of Memphis, TN Ben Walsh 2011 Rhodes Institute for Regional Studies 1 Music, like all other art forms, has multiple influences. Social movements, personal adventures and technology have all affected art in meaningful ways. The understanding of these different influences is essential for the full enjoyment and appreciation of any work of art. As a musician, specifically a bassist, I am interested in understanding, as thoroughly as 1 http://rockabillyhall.com/SunRhythm1.html (date accessed 7 /15/11). possible, the different influences contributing to the development of the bass’ roles in popular music, and specifically the sound that the bass is producing relative to the other sounds in the ensemble. I am looking to identifying some of the key influences that determined the sound that the double and electric bass guitar relative to the ensembles they play in. I am choosing to focus largely on the 1950’s as this is the era of the popularization of the electric bass guitar. With this new instrument, the sound, feeling and groove of rhythm sections were dramatically changed. However, during my research it became apparent that this shift involving the electric bass and amplification began earlier than the 1950’s. My research had to reach back to the early 1930’s. The defining characteristics of musical styles from the 1950’s forward are very much shaped by the possibilities of the electric bass guitar. This statement is not taking away from the influence and musical necessity that is the double bass, but the sound of the electric bass guitar is a defining characteristic of music from the 1950s onward. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1638 HON

E1638 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks August 7, 1998 After a successful tenure as Commander of also served as a member of the Indiana Fiscal In honoring the memory of Gibby I feel there the 88th in Minnesota, he moved on to the Policy Institute and he was a council member are a few things that I must call attention to, Pentagon. He was assigned to the Assistant for the Boy Scouts of America. a few memories that, as I am sure, everyone Deputy Chief of Staff Operations, Mobilization Wally Miller is survived by his wife, June; who knew Gibby will agree with me on, must and Reserve Affairs. In addition, General children Beth Ingram, Aimee Riemke, Tom, be mentioned. One of these was Gibby's fas- Rehkamp was named to the Reserve Forces Michael Miller, stepsons Ben, Andy Camp; cination with sports. Gibby was truly a sports Policy Board (RFPB). The RFPB is rep- mother Connie Conklin Miller; sisters Beverly fanatic. He seemed to enjoy it most, though, resented by members of all of the uniformed Stevens, Barbara Miller, brothers V. Richard, when he could share his excitement and en- services. Members of the RFPB are respon- R. James Miller; and five grandchildren. thusiasm with others. He was very successful sible for policy advising to the Secretary of In closing, I can only begin to enumerate on in spreading his love of sports in many dif- Defense on matters relating to the reserve Wally Miller's long and distinguished list of ferent ways, whether it be by working for an components. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

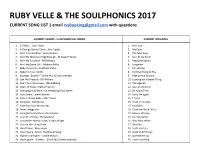

SONG LIST | Email [email protected] with Questions

RUBY VELLE & THE SOULPHONICS 2017 CURRENT SONG LIST | email [email protected] with questions CURRENT COVERS - In ALPHABETICAL ORDER CURRENT ORIGINALS 1. 25 Miles - Edwin Starr 1. Heartlite 2. A Change Gonna Come - Sam Cooke 2. My Dear 3. Ain’t It Funky Now - James Brown 3. The Man Says 4. Ain’t No Mountain High Enough - M.Gaye/T.Terrell 4. Soul of the Earth 5. Ain’t No Sunshine - Bill Withers 5. Medicine Spoon 6. Am I the Same Girl - Barbara Acklin 6. Longview 7. Baby I Love You- Aretha Franklin 7. Mr. Wrong 8. Baby It’s You - Smith 8. Coming Home to You 9. Bootleg - Booker T. & the MG’s (instrumental) 9. Feet on the Ground 10. Can We Pretend - Bill Withers 10. Looking for a Better Thing 11. Can’t Turn You Loose - Otis Redding 11. The Agenda 12. Chain of Fools- Aretha Franklin 12. Soul of the Earth 13. Champagne & Wine - Otis Redding/ Etta James 13. Its About Time 14. Cold Sweat - James Brown 14. Used Me again 15. Comin’ Home Baby - Mel Torme 15. I Tried 16. Darkness- Tab Benoit 16. Tried on A Smile 17. Fade Into You- Mazzy Star 17. Just Blink 18. Fever- Peggy Lee 18. Close the Book On Us 19. Georgia On My Mind - Ray Charles 19. Broken Women 20. Grab This Thing - The Markeys 20. Call My Name 21. Grapevine- Marvin Gaye/ Gladys Knight 21. Way Back When 22. Groove Me - King Floyd 22. Shackles 23. Hard Times - Baby Huey 23. Lost Lady Usa 24. Hava Nagila- Jewish Traditional Song 24.