Immigrants, Nurses, Soldiers, and the Transformation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2005 $2.50

American Jewish Historical Society Fall 2005 $2.50 PRESIDENTIAL DINNER 'CRADLED IN JUDEA' EXHIBITION CHANUKAH AMERICAN STYLE BOSTON OPENS 350TH ANNIVERSARY EXHIBIT FROM THE ARCHIVES: NEW YORK SECTION, NCJW NEW JEWISH BASEBALL DISCOVERIES TO OUR DONORS The American Jewish Historical Society gratefully STEVEN PLOTNICK HENRY FRIESS JACK OLSHANSKY ARNOLD J. RABINOR KARL FRISCH KATHE OPPENHEIMER acknowledges the generosity of our members and TOBY & JEROME RAPPOPORT ROBERTA FRISSELL JOAN & STEVE ORNSTEIN donors. Our mission to collect, preserve and disseminate JEFF ROBINS PHILLIP FYMAN REYNOLD PARIS ROBERT N. ROSEN DR. MICHAEL GILLMAN MITCHELL PEARL the record of the American Jewish experience would LIEF ROSENBLATT RABBI STEVEN GLAZER MICHAEL PERETZ be impossible without your commitment and support. DORIS ROSENTHAL MILTON GLICKSMAN HAROLD PERLMUTTER WALTER ROTH GARY GLUCKOW PHILLIP ZINMAN FOUNDATION ELLEN R. SARNOFF MARC GOLD EVY PICKER $100,000+ FARLA & HARVEY CHET JOAN & STUART SCHAPIRO SHEILA GOLDBERG BETSY & KEN PLEVAN RUTH & SIDNEY LAPIDUS KRENTZMAN THE SCHWARTZ FAMILY JEROME D. GOLDFISHER JACK PREISS SANDRA C. & KENNETH D. LAPIDUS FAMILY FUND FOUNDATION ANDREA GOLDKLANG ELLIOTT PRESS MALAMED NORMAN LISS EVAN SEGAL JOHN GOLDKRAND JAMES N. PRITZKER JOSEPH S. & DIANE H. ARTHUR OBERMAYER SUSAN & BENJAMIN SHAPELL HOWARD K. GOLDSTEIN EDWARD H RABIN STEINBERG ZITA ROSENTHAL DOUGLAS SHIFFMAN JILL GOODMAN ARTHUR RADACK CHARITABLE TRUST H. A. SCHUPF LEONARD SIMON DAVID GORDIS NANCY GALE RAPHAEL $50,000+ ARTHUR SEGEL HENRY SMITH LINDA GORENS-LEVEY LAUREN RAPPORT JOAN & TED CUTLER ROSALIE & JIM SHANE TAWANI FOUNDATION GOTTESTEIN FAMILY FOUNDATION JULIE RATNER THE TRUSTEES VALYA & ROBERT SHAPIRO MEL TEITELBAUM LEONARD GREENBERG ALAN REDNER UNDER THE WILL OF STANLEY & MARY ANN SNIDER MARC A. -

Ellis Island—The “Golden Door” to America

Lesson 3: Ellis Island—The “Golden Door” to America OBJECTIVES OVERVIEW Students will be able to: This lesson tells the history of Ellis Island, how and why it was • Identify the peak period of developed, and the experiences of those immigrants who passed immigration through Ellis through it. In the activity, students write the story of an immi- Island. grant passing through Ellis Island in 1907 or of an immigration • Explain what countries sent inspector working on the island. most of the immigrants in this period. • Describe the experience of an immigrant or immigration inspector by writing a fiction- NOTES al story. When students complete the activity, ask volunteers to read their stories. Consider posting the best stories on the bulletin board. STANDARDS ADDRESSED National U.S. History Standard 17: Understands massive immigration after 1870 and how new social patterns, conflicts, and ideas of national unity developed amid growing cultural diversity. (1) Understands challenges immigrants faced in society . (e.g., experiences of new immigrants . .) California History-Social Science Standard 11.2: Students analyze the . massive immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe. 1 The Immigration Debate: Historical and Current Issues of Immigration © 2003, Constitutional Rights Foundation Ellis Island—The “Golden Door” to America Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free . I lift my lamp beside the golden door! — Poem by Emma Lazarus engraved on the Statue of Liberty near Ellis Island hey came from many different foreign at New York Harbor, it was decided that a new ports: Liverpool, Bristol, Dublin, federal immigration station would be built on TBremen, Hamburg, Antwerp, Ellis Island. -

It's So Easy Being Green

National Aeronautics and Space Administration roundupLyndon B. Johnson Space Center JSC2008E020395 NASA/BLAIR It’s so easy being green APRIL 2008 ■ volume 47 ■ number 4 A few safetyrelated events have been on my mind recently, and I need your help! First of all, I want to emphasize there is nothing we do in our space program that would require us to take safety shortcuts or unnecessary risks. Spaceflight is inherently risky, including the development and testing of stateoftheart materials and designs. To be perfectly safe, we would never leave the ground, but that is not the business we chose and it is not the mission our nation gave us. But we should not and cannot add unnecessary risks. None of us should ever feel pressured to do anything we deem unsafe in order to meet a schedule. We have learned to launch when we are ready and not before, and I’m impressed with the number of times we have delayed launches because of reasonable concerns expressed by individuals. My point is: don’t let anyone pressure you into doing something that you consider unsafe. I will back you up. Second, I am concerned that there is reluctance on the part of some folks to report safety incidents such as minor injuries or mishaps or close calls. Their fear is that such reports will affect our safety metrics, such as lost time, days away, Occupational Safety and Health Administration recordable, etc. Let me state very clearly and forcefully that the sole goal of director our safety program is to make our work environment as safe as possible for all our employees. -

Punctuation and Sentence Structure

PUNCTUATION AND SENTENCE STRUCTURE Insert commas in the paragraphs below wherever they are needed, and eliminate any misused or needless commas. Ellis Island New York has reopened for business but now the customers are tourists not immigrants. This spot which lies in New York Harbor was the first American soil seen, or touched by many of the nation’s immigrants. Though other places also served as ports of entry for foreigners none has the symbolic power or Ellis Island. Between its opening in 1892 and its closing in 1954, over 20 million people about two thirds of all immigrants were detained there before taking up their new lives in the United States. Ellis Island processed over 2000 newcomers a day when immigration was at its peak between 1900 and 1920. As the end of a long voyage and the introduction to the New World Ellis Island must have left something to be desired. The “huddled masses” as the Statue of Liberty calls them indeed were huddled. New arrivals were herded about kept standing in lines for hours or days yelled at and abused. Assigned numbers they submitted their bodies to the poking and prodding of the silent slightest sign of sickness, disability or insanity. That test having been passed the immigrants faced interrogation by an official through an interpreter. Those with names deemed inconveniently long or difficult to pronounce, often found themselves permanently labeled with abbreviations of their names, or with the examination humiliation and confusion, to take the last short boat ride to New York City. For many of them and especially for their descendants Ellis Island eventually became not a nightmare but the place where life began. -

EL Education Core Practices

EL Education Core Practices A Vision for Improving Schools EL Education is a comprehensive school reform and school development model for elementary, middle, and high schools. The Core Practice Benchmarks describe EL Education in practice: what teachers, students, school leaders, families, and other partners do in fully implemented EL Education schools. The five core practices—learning expeditions, active pedagogy, school culture and character, leadership and school improvement, and structures—work in concert and support one another to promote high achievement through active learning, character growth, and teamwork. The Core Practice Benchmarks serve several purposes. They provide a comprehensive overview of the EL Education model, a planning guide for school leaders and teachers, a framework for designing professional development, and a tool for evaluating implementation. Each of the five core practices is comprised of a series of benchmarks. Each benchmark describes a particular area of practice and is organized by lettered components and numbered descriptors. A Different Approach to Teaching and Learning In EL Education schools… Learning is active. Students are scientists, urban planners, historians, and activists, investigating real community problems and collaborating with peers to develop creative, actionable solutions. Learning is challenging. Students at all levels are pushed and supported to do more than they think they can. Excellence is expected in the quality of their work and thinking. Learning is meaningful. Students apply their skills and knowledge to real-world issues and problems and make positive change in their communities. They see the relevance of their learning and are motivated by understanding that learning has purpose. Learning is public. -

Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island New Jersey and New York

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island New Jersey and New York Contact Information For more information about the Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or (212) 363-3200 or write to: Superintendent, Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island, Liberty Island, New York, NY 10004 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • The statue “Liberty Enlightening the World” is one of the world’s most recognized icons. She endures as a highly potent symbol inspiring contemplation of such ideas as liberty, freedom for all people, human rights, democracy, and opportunity. As a gift from the people of France to the people of the United States, the Statue commemorates friendship, democratic government, and the abolition of slavery. Her design, an important technological achievement of its time, continues to represent a bridge between art and engineering. • Ellis Island is the preeminent example of a government immigration and public health operation, the busiest and largest of its time. -

Serial Pinboarding in Contemporary Television

Serial Pinboarding in Contemporary Television Anne Ganzert Serial Pinboarding in Contemporary Television Anne Ganzert Serial Pinboarding in Contemporary Television Anne Ganzert University of Konstanz Konstanz, Germany ISBN 978-3-030-35271-4 ISBN 978-3-030-35272-1 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35272-1 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the pub- lisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institu- tional affiliations. -

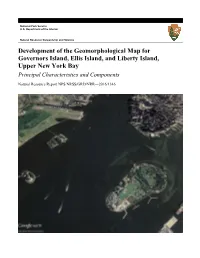

Principal Characteristics and Components

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Development of the Geomorphological Map for Governors Island, Ellis Island, and Liberty Island, Upper New York Bay Principal Characteristics and Components Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2016/1346 ON THE COVER Aerial imagery of (clockwise from left) Liberty Island, Ellis Island, and Governors Island, all managed by the National Park Service as part of the National Parks of New York Harbor. USDA Farm Service Agency imagery, obtained 15 July 2006 (pre- Sandy), extracted from Google Earth Pro on 21 April 2015. Development of the Geomorphological Map for Governors Island, Ellis Island, and Liberty Island, Upper New York Bay Principal Characteristics and Components Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2016/1346 Norbert P. Psuty, William Hudacek, William Schmelz, and Andrea Spahn Sandy Hook Cooperative Research Programs New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station Rutgers University 74 Magruder Road Highlands, New Jersey 07732 December 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. -

National Register of Historic Places

United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE 1849 C Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20240 The attached property, the Dover Green Historic District in Kent County, Delaware, reference number 77000383, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places by the Keeper of the National Register on 05/05/1977, as evidenced by FEDERAL REGISTER/WEEKLY LIST notice of Tuesday, February 6,1979, Part II, Vol. 44, No. 26, page 7443. The attached nomination form is a copy of the original documentation provided to the Keeper at the time of listing. ational Register of Historic Places Date S:/nr_nhl/jjoecke/archives/inventoriesandfrc/certificanletter/certifyletter . 1MOO ,M-*° UNITEUSTATESUti'AKl/SUti'ARl/ )M)NTOJ THE INTERIOR IFoTh, V UK ONLY NATIONALIATIONAL fAiik SESERVICfc NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY-. NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____ TYPE ALL ENTRIES •• COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS | NAME HISTORIC Dover, Brother's Portion AND/OH COMMON Dover Green Historic District | LOG ATI ON STREETINUMBER Between North, South, and East Streets ____and Governors avenue__________ .... _ _NOTFORPUiU CATION CITY.TOWH CONGRESSIONAL DISTniCT Dover One STATE CODE COUNTY Delaware 10 Kent - 001* ^CLASSIFICATION i CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENTUSE ', X-DISTRICT —PUPLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X— MUSEUM _ BUILDIMGIS) — PRIVATE — UNOCCUPIED &COMM[RaAL X— PARK —STRUCTURE X.BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -.EDUCATIONAL X_ PRIVATE RESIDENCE { — SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE — ENTERTAINMENT X_REUGtOOS — OBJECT «IN PROCESS —YES' RESTRICTED X.COVERNMENT _SC1ENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED X-YES. UNRESTRICTED ^INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY ™01HER OWNER OF PROPERTY £:tate, County, City Governments, and Private Owners STREET li NUMBER CITY. -

Finding Your Jewish Ancestors

FINDING RECORDS OF YOUR ANCESTORS Tracing your JEWisH ancestors From the United States to Europe 1850 to 1930 If you have a Jewish ancestor who came to the United States from Europe, you may need to identify the ancestor’s birthplace before you can find more generations of your family. Follow the steps in this guide to identify your ancestor’s birthplace or place of origin. These instructions tell you which records to search first, what to look for, and what research tools to use. The first part of the guide explains the process for finding the information you need. It includes examples to show how others have found information. The second part of the guide gives detailed information to help you use the records and tools. How to Find Your Ancestor’s Birthplace or Place of Origin 1 Search a U.S. census to find the country your immigrant ancestor came from and, if possible, the year of immigration. Find the specific birthplace 2 or place of origin for your immigrant ancestor in one of the following records: • Passenger arrival lists for a U.S. port. • U.S. naturalization records. • Passenger departure lists for a European port. • Jewish record collections. Now that you know your 3 ancestor’s birthplace or place of origin, look for that place in a gazetteer. The gazetteer helps you identify where records about your ancestor may have been created and kept. The steps and tools you need are described inside. HoW TO Begin—PreParation You should have already gathered as much information as Tips possible from your home and filled out a pedigree chart. -

Home Annie: Rethinking Ellis Island and Annie Moore in the Classroom Mia Mercurio

Social Education 72(4), pp 203–206, 188 ©2008 National Council for the Social Studies Welcome Home Annie: Rethinking Ellis Island and Annie Moore in the Classroom Mia Mercurio Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore; Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door! —Emma Lazarus (1883)1 he story of the United States and the people who have made it their home would ulated receiving station arose from not be complete without considering the experience of Irish immigrants— abuses immigrants encountered when Tparticularly the experience of Annie Moore, the first immigrant to be processed they landed in Manhattan: swindlers on Ellis Island. However, the story of Annie Moore, and how it has been recounted accosted immigrants with offers of food, and taught to date, is inaccurate. This article focuses on the past inaccuracy and offers housing, trinkets, and railway tickets, or guidance on how Annie Moore’s story should be taught, given the new information initiating exchanges by taking money that has surfaced about her life. but delivering no (or inferior) goods.3 Problems Faced by Social for a new life. Many stories of immigra- Ellis Island Studies Teachers tion, such as the story of Annie Moore, In 1890, New York City commissioners How social studies teachers decide what have been romanticized over the years were notified that the federal government to teach involves reflecting on and resolv- and in the process some have become would assume responsibility for immi- ing several pedagogical problems, two of untrue. -

The Island of Tears: How Quarantine and Medical Inspection at Ellis Island Sought to Define the Eastern European Jewish Immigrant, 1878-1920

The Island of Tears: How Quarantine and Medical Inspection at Ellis Island Sought to Define the Eastern European Jewish Immigrant, 1878-1920 Emma Grueskin Barnard College Department of History April 19th, 2017 Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, With conquering limbs astride from land to land; Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand Glows worldwide welcome; her mild eyes command The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame. “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door! - Emma Lazarus, “The New Colossus” (1883) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Acknowledgements 1 II. Introduction 2 Realities of Immigrant New York Historiography III. Ethical Exile: A Brief History of Quarantine and Prejudice 9 The Ethics of Quarantine Foucault and the Politics of The Ailing Body Origins of Quarantine and Anti-Jewish Sentiments IV. Land, Ho! Quarantine Policy Arrives at Ellis Island 22 Welcoming the Immigrants Initial Inspection and Life in Steerage Class Divisions On Board Cholera of 1892 and Tammany Hall Quarantine Policy V. Second Inspection: To The Golden Land or To the Quarantine Hospital 38 The Dreaded Medical Inspection Quarantine Islands, The Last Stop VI. Conclusion 56 VII. Bibliography 58 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has certainly been a labor of love, and many people were involved in its creation.