PW Integrated Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frensham Parish Council

Frensham Parish Council Village Design Statement Contents 1. What is a VDS? 2. Introduction & History 3. Open Spaces & Landscape 4. Buildings – Style & Detail 5. Highways & Byways 6. Sports & rural Pursuits Summary Guidelines & Action Points Double page spread of parish map in the centre of document Appendix: Listed Buildings & Artefacts in Parish 1 What is a Village Design Statement? A Village Design Statement (VDS) highlights the qualities, style, building materials, characteristics and landscape setting of a parish, which are valued by its residents. The background, advice and guidelines given herein should be taken into account by developers, builders and residents before considering development. The development policies for the Frensham Parish area are the “saved Policies” derived from Waverley Borough Council’s Local Plan 2002, (which has now been superseded. It is proposed that the Frensham VDS should be Supplementary Planning Guidance, related to Saved Policy D4 ‘Design and Layout’. Over recent years the Parish Council Planning Committee, seeing very many applications relating to our special area, came to the conclusion that our area has individual and special aspirations that we wish to see incorporated into the planning system. Hopefully this will make the Parish’s aspirations clearer to those submitting applications to the Borough Council and give clear policy guidance. This document cannot be exhaustive but we hope that we have included sufficient detail to indicate what we would like to conserve in our village, and how we would like to see it develop. This VDS is a ‘snapshot’ reflecting the Parish’s views and situation in2008, and may need to be reviewed in the future in line with changing local needs, and new Waverley, regional and national plans and policies. -

Download Brochure

WELCOME to BROADOAKS PAR K — Inspirational homes for An exclusive development of luxurious Built by Ernest Seth-Smith, the striking aspirational lifestyles homes by award winning housebuilders Broadoaks Manor will create the Octagon Developments, Broadoaks Park centrepiece of Broadoaks Park. offers the best of countryside living in Descending from a long-distinguished the heart of West Byfleet, coupled with line of Scottish architects responsible for excellent connections into London. building large areas of Belgravia, from Spread across 25 acres, the gated parkland Eaton Square to Wilton Crescent, Seth-Smith estate offers a mixture of stunning homes designed the mansion and grounds as the ranging from new build 2 bedroom ultimate country retreat. The surrounding apartments and 3 - 6 bedroom houses, lodges and summer houses were added to beautifully restored and converted later over the following 40 years, adding apartments and a mansion house. further gravitas and character to the site. Surrey LIVING at its BEST — Painshill Park, Cobham 18th-century landscaped garden with follies, grottoes, waterwheel and vineyard, plus tearoom. Experience the best of Surrey living at Providing all the necessities, a Waitrose Retail therapy Broadoaks Park, with an excellent range of is located in the village centre, and Guildford’s cobbled High Street is brimming with department stores restaurants, parks and shopping experiences for a wider selection of shops, Woking and and independent boutiques alike, on your doorstep. Guildford town centres are a short drive away. offering one of the best shopping experiences in Surrey. Home to artisan bakeries, fine dining restaurants Opportunities to explore the outdoors are and cosy pubs, West Byfleet offers plenty plentiful, with the idyllic waterways of the of dining with options for all occasions. -

From Topiary to Utopia? Ending Teleology and Foregrounding Utopia in Garden History

Cercles 30 (2013) FROM TOPIARY TO UTOPIA? ENDING TELEOLOGY AND FOREGROUNDING UTOPIA IN GARDEN HISTORY LAURENT CHÂTEL Université Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV) / CNRS-USR 3129 Introduction, or the greening of Utopia Utopia begs respect. More than an island, imagined or imaginary, more than a fiction, it is a word, a research area, almost a science. Utopia has lent itself to utopologia and utopodoxa, and there are utopologues and utopolists. To think out utopia is to think large and wide; to reflect on man’s utopian propensity (which strikes me as deeply, ontologically rooted) is to ponder over man’s extraversive or centrifugal dimension, whereby being in one universe (perhaps feeling constrained) he/she feels the need to re-authorise himself/herself as Architect, “skilful Gardener”, and to multiply universes within his own universe. Utopia points to an opening up of frontiers, a breaking down of dividing walls: it is about transferring other worlds into one world as if man needed to think constantly he had a plurality of worlds at hand. Our culture today is full of this taste for derivation, analogy, parallel, and mirror-effects. A photographer like Aberlado Morell has played with his irrepressible need to fuse the world ‘within’ and the world ‘without’ by offering “views with a room”.1 Nothing new there- a recycling of past techniques of image-merging such as capriccio fantasies. But such a propensity to invent and re-invent a multi-universe reaches out far and wide in contemporary global society. However, from the 1970s onwards, utopia has been declared a thing of the past - no longer a valid thinking tool of this day and age possibly because of 1 See the merging of inside and outside perspectives on his official website (last checked 21 April 2013), http://www.abelardomorell.net/ Laurent Châtel, « From Topiary to Utopia ? Ending Teleology and Foregrounding Utopia in Garden History », Cercles 30 (2013) : 95-107. -

A Case Study of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2007 Reputation in Revolutionary America: A Case Study of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson Elizabeth Claire Anderson University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Anderson, Elizabeth Claire, "Reputation in Revolutionary America: A Case Study of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson" (2007). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1040 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elizabeth Claire Anderson Bachelor of Arts 9lepu.tation in ~ Unwtica: a ~e studq- oj Samuel a.dartt;., and g fuun.a:, !JtulcIiUu,on 9JetIi~on !lWWuj ~ g~i6, Sp~ 2007 In July 1774, having left British America after serving terms as Lieutenant- Governor and Governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson met with King George III. During the conversation they discussed the treatment Hutchinson received in America: K. In such abuse, Mf H., as you met with, I suppose there must have been personal malevolence as well as party rage? H. It has been my good fortune, Sir, to escape any charge against me in my private character. The attacks have been upon my publick conduct, and for such things as my duty to your Majesty required me to do, and which you have been pleased to approve of. -

Newsletter 38 February 2017

Newsletter 38 February 2017 Membership Thank you to those of you who renewed your membership at our AGM on 1st February. May we remind you that your membership will lapse if you haven't renewed your subscription by 31st March and you will no longer receive newsletters and information from the Society. We hope that you will find something of interest in our programme and newsletters and will decide to renew your subscription and to come to our meetings. Thursday 9 March 2017, 8 pm Kenneth Wood, Molesey Architect ‘A Modernist in Suburbia’ Talk by Dr Fiona Fisher Hurst Park School, Hurst Road, KT8 1QS Kenneth Wood trained at the Polytechnic School of Architecture in Regent Street and worked for Eric Lyons before establishing his architectural and design practice at East Molesey in 1955. His work was published and exhibited in Britain and internationally in the 1950s and 1960s and was critically well-received at that time. Projects from that period include street improvement schemes, church halls and church extensions around Kingston upon Thames and in North London, a village centre at Oxshott, a youth club and a school at Kingston, and a new district headquarters for the Forestry Commission at Santon Downham in Suffolk. Wood’s firm became best known for the design of private houses in the modern style, most of which were completed in Surrey. Dr Fiona Fisher is curator of Kingston University's Dorich House Museum, the former studio home of the sculptor Dora Gordine and her husband, the Hon. Richard Hare, a scholar of Russian art and literature. -

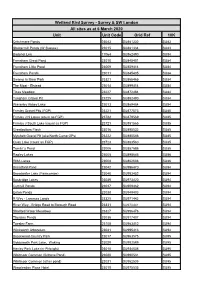

Unit Unit Code Grid Ref 10K Wetland Bird Survey

Wetland Bird Survey - Surrey & SW London All sites as at 6 March 2020 Unit Unit Code Grid Ref 10K Critchmere Ponds 23043 SU881332 SU83 Shottermill Ponds (W Sussex) 23015 SU881334 SU83 Badshot Lea 17064 SU862490 SU84 Frensham Great Pond 23010 SU845401 SU84 Frensham Little Pond 23009 SU859414 SU84 Frensham Ponds 23011 SU845405 SU84 Swamp in Moor Park 23321 SU865465 SU84 The Moat - Elstead 23014 SU899414 SU84 Tices Meadow 23227 SU872484 SU84 Tongham Gravel Pit 23225 SU882490 SU84 Waverley Abbey Lake 23013 SU869454 SU84 Frimley Gravel Pits (FGP) 23221 SU877573 SU85 Frimley J N Lakes (count as FGP) 23722 SU879569 SU85 Frimley J South Lake (count as FGP) 23721 SU881565 SU85 Greatbottom Flash 23016 SU895532 SU85 Mytchett Gravel Pit (aka North Camp GPs) 23222 SU885546 SU85 Quay Lake (count as FGP) 23723 SU883560 SU85 Tomlin`s Pond 23006 SU887586 SU85 Rapley Lakes 23005 SU898646 SU86 RMA Lakes 23008 SU862606 SU86 Broadford Pond 23042 SU996470 SU94 Broadwater Lake (Farncombe) 23040 SU983452 SU94 Busbridge Lakes 23039 SU973420 SU94 Cuttmill Ponds 23037 SU909462 SU94 Enton Ponds 23038 SU949403 SU94 R Wey - Lammas Lands 23325 SU971442 SU94 River Wey - Bridge Road to Borough Road 23331 SU970441 SU94 Shalford Water Meadows 23327 SU996476 SU94 Thursley Ponds 23036 SU917407 SU94 Tuesley Farm 23108 SU963412 SU94 Winkworth Arboretum 23041 SU995413 SU94 Brookwood Country Park 23017 SU963575 SU95 Goldsworth Park Lake, Woking 23029 SU982589 SU95 Henley Park Lake (nr Pirbright) 23018 SU934536 SU95 Whitmoor Common (Brittons Pond) 23020 SU990531 SU95 Whitmoor -

Haslemere-To-Guildford Monster Distance: 33 Km=21 Miles Moderate but Long Walking Region: Surrey Date Written: 15-Mar-2018 Author: Schwebefuss & Co

point your feet on a new path Haslemere-to-Guildford Monster Distance: 33 km=21 miles moderate but long walking Region: Surrey Date written: 15-mar-2018 Author: Schwebefuss & Co. Last update: 14-oct-2020 Refreshments: Haslemere, Hindhead, Tilford, Puttenham, Guildford Maps: Explorer 133 (Haslemere) & 145 (Guildford) Problems, changes? We depend on your feedback: [email protected] Public rights are restricted to printing, copying or distributing this document exactly as seen here, complete and without any cutting or editing. See Principles on main webpage. Heath, moorland, hills, high views, woodland, birch scrub, lakes, river, villages, country towns In Brief This is a monster linear walk from Haslemere to Guildford. It combines five other walks in this series with some short bridging sections. You need to browse, print or download the following additional walks: Hindhead and Blackdown Devil’s Punch Bowl, Lion’s Mouth, Thursley Puttenham Common, Waverley Abbey & Tilford Puttenham and the Welcome Woods Guildford, River Wey, Puttenham, Pilgrims Way Warning! This is a long walk and should not be attempted unless you are physically fit and have back-up support. Boots and covered legs are recommended because of the length of this walk. A walking pole is also recommended. This monster walk is not suitable for a dog. There are no nettles or briars to speak of. The walk begins at Haslemere Railway Station , Surrey, and ends at Guildford Railway Station. Trains run regularly between Haslemere and Guildford and both are on the line from London Waterloo with frequent connections. For details of access by road, see the individual guides. -

River Tillingbourne – Albury Estates

River Tillingbourne – Albury Estates Advisory Visit April 2018 Key Findings • The Tillingbourne through the Albury Estate land holdings does support viable wild trout habitat but is severely compromised by impounding structures on both beats. • The move to an unstocked, wild fishery will enable the wild component of the stock to develop. • Some excellent work designed to improve habitat quality has already been undertaken but the scope for further enhancement is huge. • The bottom lake on the Vale End Fishery is unsustainable, fragments river habitats, blocks natural fish migration and locally impacts water quality. Removing the dam and reinstating a natural stream would be a flagship project but would undoubtedly attract external funding and support from government agencies as well as catchment partners. • The WTT can help to prepare a costed project proposal and partner the Estate in helping to deliver a sustainable wild trout fishery at Vale End. 1 1.0 Introduction This report is the output of a site visit to the River Tillingbourne on the Albury Estate in Surrey. The Estate management currently runs a network of still-water game fisheries, primarily stocked with farm-reared rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and occasional brown trout (Salmo trutta). In addition, the Estate offers chalkstream fly fishing opportunities on two separate beats of river which run parallel with the Estate’s stocked trout lakes. The Estate also runs a section of syndicated river fishing immediately upstream of the Weston Fishery which is not included in this report. Historically, the river sections available to paying day rods have been stocked with farm-reared brown trout and the Estate have recently ceased stocking on these two day ticket beats and are looking to develop the wild component of the stock via a programme of improved habitat management. -

Shalford Trail

This heritage trail takes in the most western of the Tillingbourne villages, TILLINGBOURNE TRAILS scenic Shalford, on the banks of the River Wey. Explore the ins and outs of the original settlement, including Shalford Mill and the church of St Mary, before continuing through the meadows and along the Wey itself, absorbing both the beautiful countryside and historic monuments of the Shalford area. Length 4.5 km Duration approx. 2 hours Easy level of difficulty START from Shalford Station For more details, download the printable pdf (www.tillingbournetales.co.uk/places/trails) Returning to the A281, cross car park (GU4 8BZ). at the pedestrian crossing and Walk away from the station and, turn right along the pavement keeping to your right, walk over in front of the white cottages. the grassy triangle up to the You will soon reach the war pedestrian crossing over the memorial, the double stocks A281. and the entrance to Shalford Although the current St Mary’s was only dedicated Churchyard. in 1847, it is at least the fourth building on site Cross the A281 and turn right since the first Saxon (10th century?) church. The over the bridge. Turn left on Victorian church is built in Early English style. to the public footpath towards the wooden gates of Walk through the churchyard on a roughly diagonal course, keeping the Shalford Cemetery on your church to your right. Turn left down the narrow path between two left. memorial crosses opposite the blue doors at the side of the church. Follow the path into the trees and you will emerge onto a tarmac path, opposite the premises of the Thames Water Treatment Plant. -

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, by PAUL E

LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Class Iftttoergibe 1. ANDREW JACKSON, by W. G. BROWN. 2. JAMES B. EADS, by Louis How. 3. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, by PAUL E. MORE. 4. PETER COOPER, by R. W. RAYMOND. 5. THOMAS JEFFERSON, by H. C. MKR- WIN. 6. WILLIAM PENN, by GEORGE HODGBS. 7. GENERAL GRANT, by WALTER ALLEN. 8. LEWIS AND CLARK, by WILLIAM R. LIGHTON. 9. JOHNMARSHALL.byjAMEsB.THAYER. 10. ALEXANDER HAMILTON, by CHAS. A. CONANT. 11. WASHINGTON IRVING, by H.W.BoYN- TON. 12. PAUL JONES, by HUTCHINS HAPGOOD. 13. STEPHEN A. DOUGLAS, by W. G. BROWN. 14. SAMUEL DE CHAMPLAIN, by H. D. SEDGWICK, Jr. Each about 140 pages, i6mo, with photogravure portrait, 65 cents, net ; School Edition, each, 50 cents, net. HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY BOSTON AND NEW YORK fotorafoe Biographical Series NUMBER 3 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN BY PAUL ELMER MORE UNIV. or CALIFORNIA tv ...V:?:w BENJAMIN FRANKLIN BY PAUL ELMEK MORE BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY fftiteitfibe pre0 Camferibge COPYRIGHT, igOO, BY PAUL E. MORE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CONTENTS CHAP. **< I. EARLY DAYS IN BOSTON .... 1 II. BEGINNINGS IN PHILADELPHIA AND FIRST VOYAGE TO ENGLAND .... 22 III. RELIGIOUS BELIEFS. THE JUNTO . 37 " IV. THE SCIENTIST AND PUBLIC CITIZEN IN PHIL ADELPHIA 52 V. FIRST AND SECOND MISSIONS TO ENGLAND . 85 VI. MEMBER OF CONGRESS ENVOY TO FRANCE 109 227629 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN EAKLY DAYS IN BOSTON WHEN the report of Franklin s death reached Paris, he received, among other marks of respect, this significant honor by one of the revolutionary clubs : in the cafe where the members met, his bust was crowned with oak-leaves, and on the pedestal below was engraved the single word VIR. -

3A High Street, Esher, Surrey, KT10 9RL £1,400Pcm Unfurnished Available Now

t: 01483 285255 m: 07501 525058 [email protected] www.elizabethhuntassociates.co.uk 3a High Street, Esher, Surrey, KT10 9RL £1,400pcm Unfurnished Available Now IMMACULATE FIRST FLOOR APARTMENT IN THE HEART OF THE TOWN CENTRE, WITHIN EASY REACH OF RAIL STATION Accommodation Ideally situated in the heart of Esher’s town centre is this immaculate first floor 2 bedroom Ÿ Large reception hall with apartment that has been completely refurbished to a high standard. The property features storage space wood floors throughout, a well-appointed galley kitchen with integrated appliances and Ÿ Double aspect reception wooden counter top, new bathroom and its own delightful roof terrace. Please note: there room is no parking associated with this property. Ÿ Galley kitchen with range of integrated appliances Esher’s eclectic High Street offers a range of local stores, fashion boutiques, cinema, bars Ÿ 2 bedrooms and restaurants serving a variety of international cuisines. The property is close to excellent Ÿ Bathroom with shower schools including Claremont Fan Court and Milbourne Lodge schools in Esher, the ACS over bath International School, Reeds School, Notre Dame, Parkside and Feltonfleet schools in Ÿ Private roof terrace Cobham, Danes Hill and Royal Kent Primary School in Oxshott, Walton Oak School, accessed via reception Danesfield Manor School and Ashley Primary School in Walton on Thames, St George’s hall School and College in Weybridge, and a little further away are Downside School and St John’s School in Leatherhead. Within walking distance of Esher’s mainline rail station which (Photos as previously provides regular services to London Waterloo and Victoria (approximately 40-50 minutes), furnished) the A3 and M25 motorways are within easy reach, leading to Heathrow and Gatwick airports. -

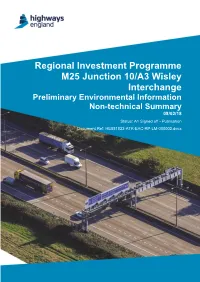

Preliminary Environmental Information Report Non-Technical Summary

Regional Investment Programme M25 Junction 10/A3 Wisley Interchange Preliminary Environmental Information Non-technical Summary 08/02/18 Status: A1 Signed off - Publication Document Ref: HE551522-ATK-EAC-RP-LM-000002.docx Regional Investment Programme M25 Junction 10/A3 Wisley Interchange Preliminary Environmental Information Report Non-technical Summary Notice This document and its contents have been prepared and are intended solely for Highways England’s information and use in relation to M25 Junction10/A3 Wisley Interchange Atkins Limited assumes no responsibility to any other party in respect of or arising out of or in connection with this document and/or its contents. This document has 15 pages including the cover. Document history Job number: HE551522 Document ref: HE551522-ATK-EAC-RP-LM-000002 Purpose Revision Status Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date description Issue for C02 A1 JB NDW AMB GB 08/02/18 Consultation C01 A1 For HE Review JB NDW AMB AEM 06/02/18 Revision C02 Page 2 of 15 Regional Investment Programme M25 Junction 10/A3 Wisley Interchange Preliminary Environmental Information Report Non-technical Summary Table of contents Chapter Pages 1. Introduction 5 1.1 Background to the non-technical summary 5 1.2 Overview of project 5 1.3 Purpose of the PEIR 7 1.4 Need for the project 8 1.5 Consultation 8 1.6 Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) 9 2. Air Quality 9 3. Noise and Vibration 10 4. Biodiversity 10 5. Road Drainage and the Water Environment 11 6. Landscape 12 7. Geology and Soils 12 8. Cultural Heritage 12 9. People and Communities 13 10.