MICHAEL LOWENSTERN New World Records 80468 Spasm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 23, 2016 CONTACT: Ren Mitchell 832-314-9994 [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 23, 2016 CONTACT: Ren Mitchell 832-314-9994 [email protected] Karen Stokes Dance presents DEEP: Seaspace at Zilkha Hall, Hobby Center for Performing Arts HOUSTON, TX: Karen Stokes Dance presents “DEEP: Seaspace” October 20-22, 2016 at 8:00pm at the Hobby Center for Performing Arts, Zilkha Hall. “DEEP: Seaspace” is the culminating performance of a multi-year initiative inspired by the history and landmarks of the City of Houston. With an original score by composer Bill Ryan played live by nationally recognized musicians, the evening length live performance will explore Houston for two if its defining industries: sea and space. “DEEP: Seaspace” fuses history, landscape, dance, and music through the lens of two iconic Houston enterprises: The Houston Ship Channel and NASA. While Sea speaks to the pioneering spirit of the founding of Houston along the banks of Buffalo Bayou and the formation of the Houston Ship Channel, Space is inspired by Houston’s stronghold in space exploration and human achievement. Celebrating Houston's unique heritage and Texas’ pioneering spirit, “DEEP: Seaspace” investigates the core of human progress, the fundamental spirit of Houston, and the desire to understand the unknown to forge a better tomorrow. In “DEEP: Seaspace,” Stokes explores “launching” and “landing” through a unique blend of quirky and innovative choreographic styles that has become the trademark of her 20 years of work in contemporary dance. Stokes has received regional and national acclaim for her choreography including being name “Best Choreographer in Houston” in both 2014 and 2015 by the Houston Press. Nancy Wozny, of Texas Arts & Culture, wrote: “In Houston, it’s Karen Stokes who comes to mind as an artist tightly tied to Texas. -

Guest Artist Recital: Michael Lowenstern, Bass Clarinet & Electronics Michael Lowenstern

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-21-2004 Guest Artist Recital: Michael Lowenstern, bass clarinet & electronics Michael Lowenstern Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lowenstern, Michael, "Guest Artist Recital: Michael Lowenstern, bass clarinet & electronics" (2004). All Concert & Recital Programs. 3478. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/3478 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. VISITING ARTISTS SERIES 2004-5 Michael Lowenstem, bass clarinet arid electronics . ' Hockett Family Recital Hall Tuesday, September 21, 2004 8:15 p.m. ITHACA Michael Lowenstern, bass clarinet and electronics 1985 Michael Lowenstern (b. 1968) Summertime George Gershwin (1898-1937) Sha Michael Lowenstern INTERMISSION Ten Children Michael Lowenstern Spasm Michael Lowenstern But Would She Remember You? Michael Lowenstern Michael Lowenstern Michael Lowenstern, considered one of the finest bass clarinetists in the world, has performed, recorded, and toured the United States nd abroad both as a soloist and with ensembles of every variety. le is on the roster of the New Jersey Symphony, and has performed and recorded with groups as diverse as the Klezmatics, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, Steve Reich and Musicians, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and Bang on a Can All-Stars. Also active as a composer, Michael has written music for concert, recordings, dance, film, media, and his own performing ensembles. He is a composer for Grey Advertising's internet division and has written music for clients such as Oracle, Warner Brothers, Chase Manhattan Bank, and British Airways. -

The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration Into the Modern Clarinet Studio

UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones 5-1-2015 The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio Jennifer Beth Iles University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Music Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Iles, Jennifer Beth, "The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio" (2015). UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones. Paper 2367. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Scholarship@UNLV. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses/ Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE BASS CLARINET: SUPPORT FOR ITS INTEGRATION INTO THE MODERN CLARINET STUDIO By Jennifer Beth Iles Bachelor of Music Education McNeese State University 2005 Master of Music Performance University of North Texas 2008 A doctoral document submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada Las Vegas May 2015 We recommend the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Jennifer Iles entitled The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music Marina Sturm, D.M.A., Committee Chair Cheryl Taranto, Ph.D., Committee Member Stephen Caplan, D.M.A., Committee Member Ken Hanlon, D.M.A., Committee Chair Margot Mink Colbert, B.S., Graduate College Representative Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D., Interim Dean of the Graduate College May 2015 ii ABSTRACT The bass clarinet of the twenty-first century has come into its own. -

Contemporary Music Ensemble

Suffolk County Community College • Music Department • Ammerman Campus Presents Contemporary Music Ensemble Spring Concert May 11, 2002 7:30 PM Islip Arts Building, Shea Theatre Contemporary Music Ensemble William Ryan, Director ________________________________________________ Electric Counterpoint (1987) Steve Reich (b. 1936) Gerry Rulon-Maxwell, electric guitar Pat Metheny, recorded electric guitars Original Blend (2002) William Ryan (b. 1968) World Premiere Todd Reynolds, violin Michael Lowenstern, bass clarinet Frank Monastero, piano Justin Cunningham, percussion Monkey Forest (2002) Evan Ziporyn (b. 1959) Commissioned by the SCCC Contemporary Music Ensemble Lauren Kasper, flute Brett Colangelo, percussion Anne McInerney, flute Michael Clark, electric guitar Antoinette Blaikie, english horn Keith DeMaio, piano Jennifer Decaneo, clarinet Lisa Casal, violin Lauren Kohler, clarinet Miyo Davis, violin Marissa Sampson, baritone saxophone Malachy Gately, violin Duane Haynes, trumpet Laura Khalil, violin Michael Sarling, trumpet Jamie Carrillo, viola Hector Minaya, trombone Gerry Rulon-Maxwell, electric bass Justin Cunningham, percussion Robert Tavolaro, electric bass featuring special guests Michael Lowenstern, clarinet Todd Reynolds, violin _________________________________________________________________ Special thanks to Chris Kerensky for providing the english horn for Monkey Forest. Guest Performer Biographies Considered the pre-eminent bass clarinetist of his generation, Michael Lowenstern has performed to critical and popular acclaim throughout the Americas and Europe. He has performed, recorded and toured the U.S. and abroad with ensembles of every variety including The Klezmatics, The Steve Reich Ensemble, The Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, with whom he will be touring throughout the summer and fall of 2001. In September 2000, Lowenstern accepted an appointment with the New Jersey Symphony. -

The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S

Vol. 47 • No. 2 March 2020 — 2020 ICA HONORARY MEMBERS — Ani Berberian Henri Bok Deborah Chodacki Paula Corley Philippe Cuper Stanley Drucker Larry Guy Francois Houle Seunghee Lee Andrea Levine Robert Spring Charles West Michael Lowenstern Anthony McGill Ricardo Morales Clarissa Osborn Felix Peikli Milan Rericha Jonathan Russell Andrew Simon Greg Tardy Annelien Van Wauwe Michele VonHaugg Steve Williamson Yuan Yuan YaoGuang Zhai Interview with Robert Spring | Rediscovering Ferdinand Rebay Part 3 A Tribute to the Hans Zinner Company | The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S. Howland Life Without Limits Our superb new series of Chedeville Clarinet mouthpieces are made in the USA to exacting standards from the finest material available. We are excited to now introduce the new ‘Chedeville Umbra’ and ‘Kaspar CB1’ Clarinet Barrels, the first products in our new line of high quality Clarinet Accessories. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] t is once again time for the membership to vote in the EDITORIAL BOARD biennial ICA election of officers. You will find complete Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, information about the slate of candidates and voting Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder instructions in this issue. As you may know, the ICA MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR bylaws were amended last summer to add the new position Gregory Barrett I [email protected] of International Vice President to the Executive Board. This position was added in recognition of the ICA initiative to AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR engage and cultivate more international membership and Kip Franklin [email protected] participation. -

Doctoral Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO ADAM CUTHBÉRT’S WORKS FOR SOLO TRUMPET AND ABLETON SOFTWARE A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By BENJAMIN L. HAY Norman, Oklahoma 2019 A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO ADAM CUTHBÉRT’S WORKS FOR SOLO TRUMPET AND ABLETON SOFTWARE A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY Dr. Karl Sievers, Chair Dr. Irvin Wagner Dr. Marvin Lamb Dr. Matthew Stock Dr. Kurt Gramoll © Copyright by Benjamin Hay 2019 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements Thanks to Adam Cuthbért, whose generosity enabled this project to reach fruition, and whose music has inspired me to become a better artist, performer, and academic. To John Adler, Samuel Wells, Christopher Degado, and Elizabeth Jurd: thank you for sharing your wealth of knowledge, to the great benefit of this endeavor. Thank you to my committee members Marvin Lamb, Matthew Stock, Irvin Wagner, and Kurt Gramoll. Your guidance, patience, and professionalism have been a model that I hope to imitate throughout my career. A special thank you to my advisor, committee chair, mentor, and trumpet teacher, Karl Sievers. Your influence on my life has been substantial, and I will continue to aspire to be the person that you believe I can be. I cannot thank you enough. To John Marchiando, Jacob Walburn, Andrew Cheetham, and William Ballenger: thank you for all of the guidance in trumpet and life. You have made more of a difference in my life than you can ever imagine. -

Michael Lowenstern, Clarinets and Electronics Department of Music, University of Richmond

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Department Concert Programs Music 3-2-2005 Michael Lowenstern, clarinets and electronics Department of Music, University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, University of Richmond, "Michael Lowenstern, clarinets and electronics" (2005). Music Department Concert Programs. 339. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs/339 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Concert Programs by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND DEPARTMENT oF Music UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll\lllllllllll\11111111111 , 3 3082 00890 9565 Michael Lowenstem clarinets and electronics MARCH 2, 2005, 7:30PM CAMP CoNCERT HALL BooKER HALL OF Music Michael Lowenstern, considered one of the finest bass clarinet ists in the world, has performed, recorded and toured the U.S. and abroad both as a soloist and with ensembles of every variety. He is on the roster of the New Jersey Symphony, and has performed and recorded with musicians groups as diverse as The Klezmatics, Or pheus Chamber Orchestra, Steve Reich and Musicians, The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center and John Zorn. Also active as a composer, Michael has written music for concert, film, dance and the Internet, as well as his own performing ensembles. Actively involved with new technology in sound and music, Michael is one of this country's leading producers of creative electro-acous tic music, both for his own works and in collaboration with other composers. -

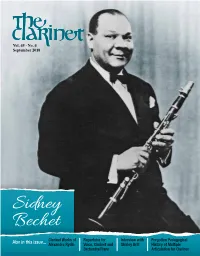

Sidney Bechet Clarinet Works of Repertoire for Interview with Forgotten Pedagogical Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 4 September 2018 Sidney Bechet Clarinet Works of Repertoire for Interview with Forgotten Pedagogical Also in this issue... Alexandre Rydin Voice, Clarinet and Shirley Brill History of Multiple Orchestra/Piano Articulation for Clarinet D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear Members and Jessica Harrie Friends of the International Clarinet Association: [email protected] s I write this message just days after the conclusion of EDITORIAL BOARD ClarinetFest® 2018, I continue to marvel at the fantastic Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, festival held on the beautiful Belgian coast of Ostend. We Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder are grateful to our friends Eddy Vanoosthuyse, artistic Adirector of ClarinetFest® 2018, and the Ostend team and family of MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR the late Guido Six – Chantal Six Vandekerckhove, Bert Six and Gaby Gregory Barrett – [email protected] Six – who together organized a truly extraordinary and memorable festival featuring artists from over 55 countries. AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR The first day alone contained an amazing array of concerts Chris Nichols – [email protected] including an homage to the legendary Guido Six by the Claribel Clarinet Choir, followed by the Honorary Member concert featuring Caroline Hartig GRAPHIC DESIGN Karl Leister, Luis Rossi, Antonio Saiote and the newest ICA honorary Karry Thomas Graphic Design member inductee, Charles Neidich. Later that evening was the [email protected] world premiere of the Piovani Clarinet Concerto with the Brussels Philharmonic, performed by Artistic Director Eddy Vanoosthuyse. -

Open Ears 25: the Marathon Concert

presents Open Ears 25: The Marathon Concert March 31, 2004 11:00AM-2:00PM Shea Theatre, Ammerman Campus FREE ADMISSION Open Ears 25: The Marathon Concert Program Premonition (1997)………………………………………..…………………Phil Kline (b. 1953) SCCC Contemporary Music Ensemble Ray Altman Vanessa Laurenti Dan Campbell Michael Macchio Jamie Carrillo Paul Micca Marc David Elona Migirov Joe Ekster Kevin Reidy Frank Gilchriest Kirsy Rosa Nichole Heid David Ruckel Alex Imbo Charles Santangelo Melissa Farrish Dan Sarno Ryan Kaelin Carolyn Track John Kelly Kaitlyn Weeks Megan Kelley Fred Wilson Holly's Tune (2004)……………………………………………………Michael Lipsey (b. 1965) World Premiere Dhumta kaDhum (2004)………………………..………………...River Guerguerian (1967) World Premiere River Guerguerian, percussion Michael Lipsey, percussion Sha (2003)…………………………………………………………Michael Lowenstern (b. 1968) Michael Lowenstern, bass clarinet Postcards from Rio (2002)…..………………………………..……..Perry Goldstein (b. 1952) Justin Comito, trombone Patrick Armann, Marimba Grande Etude Symphonique (2003)……...………………………….……Phil Kline (b. 1953) Todd Reynolds, violin Pattern Transformations (1988)……………...…………………………Lukas Ligeti Shifty (2001)…………………………………………………………..Dennis Desantis (b. 1973) So Percussion Quartet Todd Meehan Douglas Perkins Adam Sliwinsky Jason Treuting Blurred (2003)…..………………………………..……………………....William Ryan (b. 1968) World Premiere Todd Reynolds, violin Ralph Farris, viola Dorothy Lawson, cello Taimur Sullivan, soprano saxophone Stephen Gosling, piano Michael Lowenstern, bass clarinet Todd Meehan, percussion Douglas Perkins, percussion Adam Sliwinsky, percussion Jason Treuting, percussion á.X. (2004)………………………………………..…………………..Daniel Weymouth (b. 1953) World Premiere Stony Brook Contemporary Chamber Players Sarah Wall, oboe Sixxen: Michael Aberback Russell Greenberg Michael McCurdy Brian Pantekoek Antonio Ian Matthew Ward Valentine's Day (2004)…………………..……..……………….…….Todd Reynolds (b. 1964) members of Ethel Todd Reynolds, violin Ralph Farris, viola Dorothy Lawson, cello Sequenza VIIb (1969/93)……………………………………………….Luciano Berio (b. -

Michael Lowenstern, Bass Clarinet Michael Lowenstern

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 11-13-1997 Guest Artist Recital: Michael Lowenstern, bass clarinet Michael Lowenstern Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Lowenstern, Michael, "Guest Artist Recital: Michael Lowenstern, bass clarinet" (1997). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4746. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4746 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. GUEST ARTIST RECITAL Michael Lowenstern, bass clarinet Faux (1997) Michael Lowenstem Duo (1983) Theo Loevendie Spasm (1993) Michael Lowenstem Rare Events (1994) Daniel Weymouth Pushing Up Daisies (1992) Michael Lowenstem King Friday (1997) Michael Lowenstern INTERMISSION Summertime (1935) George Gershwin ( 1898-1937) Joint Session (1992) Arthur Kreiger (b. 1945) But Would She Remember You (1996) Michael Lowenstern Ford Hall Auditorium Thursday, November 13, 1997 8:15 p.m. Michael Lowenstern has performed extensively both as soloist as well as with various groups throughout the United States, Canada and Europe, including Bun Ching Lam's Chinese shadow puppet opera The Child God, After She Squawks with choreographer Stephanie Skura, the Van Gogh Video Opera with Michael Gordon and numerous performances with Portable Electronic Coffee House, a multi-media, interactive electronic music group he co-founded. He was a featured guest artist at the 1994 International Clarinet Association Conference in Chicago and in November of that year was invited to perform a solo concert to open the "Liineburg 1000-Year-Jubilee" New Music Festival in Liineburg, Germany. -

The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration Into the Modern Clarinet Studio

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2015 The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio Jennifer Beth Iles University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Music Education Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Iles, Jennifer Beth, "The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio" (2015). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2367. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7645923 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE BASS CLARINET: SUPPORT FOR ITS INTEGRATION INTO THE MODERN CLARINET STUDIO By Jennifer Beth Iles Bachelor of Music Education -

Clarinet Day 2018

The Metropolitan Youth Orchestra of New York Clarinet Day 2018 Sunday, April 22, 2018 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM Jeanne Rimsky Theater Landmark on Main Street Port Washington, NY 11050 SCHEDULE 9:00 - 9:30 AM Check in, Raffle, and Introductions 9:30 - 11:30 AM Masterclass with Anthony McGill 11:30 AM - 12:00 PM Q&A with Anthony McGill 12:00 - 1:30 PM Lunch Vendor station will be open during lunch to try Vandoren mouthpieces, reeds, ligatures Visit with a representative from Interlochen Center for the Arts to learn more about their clarinet programming 1:30 - 3:30 PM Masterclass with Michael Lowenstern 3:30 - 4:00 PM Q&A with Michael Lowenstern 4:00 - 5:00 PM Clarinet Choir Reading Session Repertoire: Uptown Funk (arr. Lowenstern); Londonderry Air; Holst Second Suite in F Thank you to our 2018 Clarinet Day Sponsors Contact MYO www.myo.org | 516-365-6961 Anthony McGill Masterclass Sonata in C Minor (1732) Georg Philipp Telemann Allegro (1681—1767) Adagio ed. Himie Voxman Allegro assai Ondeggiando, ma non troppo Thomas Young - Age 11 | United Nations International School Sandra Baskin, piano Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 (1791) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart I. Allegro (1756—1791) Ju Young Yi - Age 17 | Herricks High School Sandra Baskin, piano Concertino in E-flat Major, Op. 26 (1811) Carl Maria von Weber (1786—1826) Kenny Kim - Age 15 | Roslyn High School Sandra Baskin, piano Excerpts from: Brahms — Symphony No. 3 Kodály — Dances of Galanta Rimsky-Korsakov — Capriccio Espagnol Nicholas Hamblin - Age 16 | Riverview Community High School Michael Lowenstern Masterclass Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1942) Leonard Bernstein I.