Draft Wilderness Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Park Service Centennial and a Great Opportunity

CanyonVIEWS Volume XXIII, No. 4 DECEMBER 2016 Interview with Superintendent Chris Lehnertz Celebrating 100 Years: National Park Service Centennial An Endangered Species Recovers The official nonprofit partner of Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon Association Canyon Views is published by the Grand Canyon Association, the National Park Service’s official nonprofit partner, raising private funds to benefit Grand Canyon National Park, operating retail stores and visitor centers within the park and providing premier educational opportunities about the natural and cultural history of Grand Canyon. FROM THE CEO You can make a difference at Grand Canyon! Memberships start at $35 annually. For more What a year it’s been! We celebrated the 100th anniversary information about GCA or to become a member, of the National Park Service, and together we kicked off critically please visit www.grandcanyon.org. important conservation, restoration and education programs here at Board of Directors: Stephen Watson, Board the Grand Canyon. Thank you! Chair; Howard Weiner, Board Vice Chair; Lyle Balenquah; Kathryn Campana; Larry Clark; Sally Clayton; Richard Foudy; Eric Fraint; As we look forward into the next 100 years of the National Park Robert Hostetler; Julie Klapstein; Kenneth Service at Grand Canyon National Park, we welcome a new partner, Lamm; Robert Lufrano; Mark Schiavoni; Marsha Superintendent Chris Lehnertz. This issue features an interview with Sitterley; T. Paul Thomas the park’s new leader. I think you will find her as inspirational as we Chief Executive Officer: Susan Schroeder all do. We look forward to celebrating Grand Canyon National Park’s Chief Philanthropy Officer: Ann Scheflen Centennial in 2019 together! Director of Marketing: Miriam Robbins Edited by Faith Marcovecchio We also want to celebrate you, our members. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION 1 Using this book 2 Visiting the SouthWestern United States 3 Equipment and special hazards GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK 4 Visiting Grand Canyon National Park 5 Walking in Grand Canyon National Park 6 Grand Canyon National Park: South Rim, rim-to-river trails Table of Trails South Bass Trail Hermit Trail Bright Angel Trail South Kaibab Trail Grandview Trail New Hance Trail Tanner Trail 7 Grand Canyon National Park: North Rim, rim-to-river trails Table of Trails Thunder River and Bill Hall Trails, with Deer Creek Extension North Bass Trail North Kaibab Trail Nankoweap Trail 8 Grand Canyon National Park: trans-canyon trails, North and South Rim Table of Trails Escalante Route: Tanner Canyon to New Hance Trail at Red Canyon Tonto Trail: New Hance Trail at Red Canyon to Hance Creek Tonto Trail: Hance Creek to Cottonwood Creek Tonto Trail: Cottonwood Creek to South Kaibab Trail Tonto Trail: South Kaibab Trail to Indian Garden Tonto Trail: Indian Garden to Hermit Creek Tonto Trail: Hermit Creek to Boucher Creek Tonto Trail: Boucher Creek to Bass Canyon Clear Creek Trail 9 Grand Canyon National Park: South and North Rim trails South Rim Trails Rim Trail Shoshone Point Trail North Rim Trails Cape Royal Trail Cliff Springs Trail Cape Final Trail Ken Patrick Trail Bright Angel Point Trail Transept Trail Widforss Trail Uncle Jim Trail 10 Grand Canyon National Park: long-distance routes Table of Routes Boucher Trail to Hermit Trail Loop Hermit Trail to Bright Angel Trail Loop Cross-canyon: North Kaibab Trail to Bright Angel Trail South -

1. WEB SITE RESEARCH Topic Research: Grand Canyon Travel

1. WEB SITE RESEARCH Topic research: Grand Canyon Travel Guide 1. What is the educational benefit of the information related to your topic? Viewers will learn about places to visit and things to do at Grand Canyon National Park. 2. What types of viewers will be interested in your topic? Visitors from U.S. and around the world who plan to visit Grand Canyon 3. What perceived value will your topic give to your viewers? The idea on how to get to the Grand Canyon and what kinds of activities that they can have at the Grand Canyon. 4. Primary person(s) of significance in the filed of your topic? The Grand Canyon National Park is the primary focus of my topic. 5. Primary person(s) that made your topic information available? The information was providing by the National Park Service, Wikitravel and Library of the Congress. 6. Important moments or accomplishments in the history of your topic? In 1919, The Grand Canyon became a national park in order to give the best protection and to preserve all of its features. 7. How did the media of times of your topic treat your topic? On February 26, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson signed into law a bill establishing the Grand Canyon as one of the nation's national parks. 8. Current events related to your topic? Italian Developers want to build big resort, shopping mall, and housing complex near Grand Canyon. They started buying land near South Rim of the Grand Canyon and building a project. 9. ListServ discussion and social media coverage of your topic? Grand Canyon Hikers group in Yahoo Group and Rafting Grand Canyon Group. -

Structural Geology and Hydrogeology of the Grandview Breccia Pipe, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona M

Structural Geology and Hydrogeology of the Grandview Breccia Pipe, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona M. Alter, R. Grant, P. Williams & D. Sherratt Grandview breccia pipe on Horseshoe Mesa, Grand Canyon, Arizona March 2016 CONTRIBUTED REPORT CR-16-B Arizona Geological Survey www.azgs.az.gov | repository.azgs.az.gov Arizona Geological Survey M. Lee Allison, State Geologist and Director Manuscript approved for publication in March 2016 Printed by the Arizona Geological Survey All rights reserved For an electronic copy of this publication: www.repository.azgs.az.gov Printed copies are on sale at the Arizona Experience Store 416 W. Congress, Tucson, AZ 85701 (520.770.3500) For information on the mission, objectives or geologic products of the Arizona Geological Survey visit www.azgs.az.gov. This publication was prepared by an agency of the State of Arizona. The State of Arizona, or any agency thereof, or any of their employees, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed in this report. Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the State of Arizona. Arizona Geological Survey Contributed Report series provides non-AZGS authors with a forum for publishing documents concerning Arizona geology. While review comments may have been incorpo- rated, this document does not necessarily conform to AZGS technical, editorial, or policy standards. The Arizona Geological Survey issues no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding the suitability of this product for a particular use. -

1988 Backcountry Management Plan

Backcountry Management Plan September 1988 Grand Canyon National Park Arizona National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior (this version of the Backcountry Management Plan was reformatted in April 2000) Recommended by: Richard Marks, Superintendent, Grand Canyon National Park, 8/8/88 Approved by: Stanley T Albright, Regional Director Western Region, 8/9/88 2 GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK 1988 BACKCOUNTRY MANAGEMENT PLAN Table of Contents A. Introduction __________________________________________________________________ 4 B. Goals ________________________________________________________________________ 4 C. Legislation and NPS Policy ______________________________________________________ 5 D. Backcountry Zoning and Use Areas _______________________________________________ 6 E. Reservation and Permit System __________________________________________________ 6 F. Visitor Use Limits ______________________________________________________________7 G.Use Limit Explanations for Selected Use Areas _____________________________________ 8 H.Visitor Activity Restrictions _____________________________________________________ 9 I. Information, Education and Enforcement_________________________________________ 13 J. Resource Protection, Monitoring, and Research ___________________________________ 14 K. Plan Review and Update _______________________________________________________15 Appendix A Backcountry Zoning and Use Limits __________________________________ 16 Appendix B Backcountry Reservation and Permit System __________________________ 20 -

Grand Canyon National Park

To Bryce Canyon National Park, KANAB To St. George, Utah To Hurricane, Cedar City, Cedar Breaks National Monument, To Page, Arizona To Kanab, Utah and St. George, Utah V and Zion National Park Gulch E 89 in r ucksk ive R B 3700 ft R M Lake Powell UTAH 1128 m HILDALE UTAH I L ARIZONA S F COLORADO I ARIZONA F O gin I CITY GLEN CANYON ir L N V C NATIONAL 89 E 4750 ft N C 1448 m RECREATION AREA A L Glen Canyon C FREDONIA I I KAIBAB INDIAN P Dam R F a R F ri U S a PAGE RESERVATION H 15 R i ve ALT r 89 S 98 N PIPE SPRING 3116 ft I NATIONAL Grand Canyon National Park 950 m 389 boundary extends to the A MONUMENT mouth of the Paria River Lees Ferry T N PARIA PLATEAU To Las Vegas, Nevada U O Navajo Bridge M MARBLE CANYON r e N v I UINKARET i S G R F R I PLATEAU F I 89 V E R o V M L I L d I C a O r S o N l F o 7921ft C F 2415 m K I ANTELOPE R L CH JACOB LAKE GUL A C VALLEY ALT P N 89 Camping is summer only E L O K A Y N A S N N A O C I O 89T T H A C HOUSE ROCK N E L E N B N VALLEY YO O R AN C A KAIBAB NATIONAL Y P M U N P M U A 89 J L O C FOREST O K K D O a S U N Grand Canyon National Park- n F T Navajo Nation Reservation boundary F a A I b C 67 follows the east rim of the canyon L A R N C C Y r O G e N e N E YO k AN N C A Road to North Rim and all TH C OU Poverty Knoll I services closed in winter. -

Grand Canyon Archaeological Site

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE ETIQUETTE POLICY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE ETIQUETTE POLICY For Colorado River Commercial Operators This etiquette policy was developed as a preservation tool to protect archaeological sites along the Colorado River. This policy classifies all known archaeological sites into one of four classes and helps direct visitors to sites that can withstand visitation and to minimize impacts to those that cannot. Commercially guided groups may visit Class I and Class II sites; however, inappropriate behaviors and activities on any archaeological site is a violation of federal law and Commercial Operating Requirements. Class III sites are not appropriate for visitation. National Park Service employees and Commercial Operators are prohibited from disclosing the location and nature of Class III archaeological sites. If clients encounter archaeological sites in the backcountry, guides should take the opportunity to talk about ancestral use of the Canyon, discuss the challenges faced in protecting archaeological resources in remote places, and reaffirm Leave No Trace practices. These include observing from afar, discouraging clients from collecting site coordinates and posting photographs and maps with location descriptions on social media. Class IV archaeological sites are closed to visitation; they are listed on Page 2 of this document. Commercial guides may share the list of Class I, Class II and Class IV sites with clients. It is the responsibility of individual Commercial Operators to disseminate site etiquette information to all company employees and to ensure that their guides are teaching this information to all clients prior to visiting archaeological sites. Class I Archaeological Sites: Class I sites have been Class II Archaeological Sites: Class II sites are more managed specifically to withstand greater volumes of vulnerable to visitor impacts than Class I sites. -

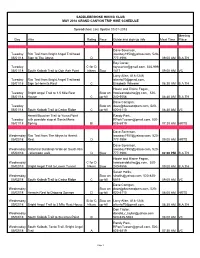

Day Hike Rating Pace Guide and Sign-Up Info Meet Time Meeting

SADDLEBROOKE HIKING CLUB MAY 2018 GRAND CANYON TRIP HIKE SCHEDULE Spreadsheet Last Update 03-01-2018 Meeting Day Hike Rating Pace Guide and sign-up info Meet Time Place Dave Sorenson, Tuesday Rim Trail from Bright Angel Trailhead [email protected], 520- 05/01/18 Sign to The Abyss D 777-1994 09:00 AM B.A.TH Roy Carter, Tuesday C for D [email protected], 520-999- 05/01/18 South Kaibab Trail to Ooh Aah Point hikers Slow 1417 09:00 AM VC Larry Allen, 818-1246, Tuesday Rim Trail from Bright Angel Trailhead [email protected], 05/01/18 Sign to Hermits Rest C Elisabeth Wheeler 08:30 AM B.A.TH Howie and Elaine Fagan, Tuesday Bright Angel Trail to 1.5 Mile Rest Slow on [email protected], 520- 05/01/18 House C up-hill 240-9556 08:30 AM B.A.TH Dave Corrigan, Tuesday Slow on [email protected], 520- 05/01/18 South Kaibab Trail to Cedar Ridge C up-hill 820-6110 08:30 AM VC Hermit/Boucher Trail to Yuma Point Randy Park, Tuesday with possible stop at Santa Maria [email protected], 520- 05/01/18 Spring B! 825-6819 07:30 AM HRTS Dave Sorenson, Wednesday Rim Trail from The Abyss to Hermit [email protected], 520- 05/02/18 Rest D 777-1994 09:00 AM HRTS Dave Sorenson, Wednesday Historical Buildings Walk on South Rim [email protected], 520- 05/02/18 - afternoon walk D Slow 777-1994 02:00 PM B.A.TH Howie and Elaine Fagan, Wednesday C for D [email protected], 520- 05/02/18 Bright Angel Trail to Lower Tunnel hikers Slow 240-9556 09:00 AM B.A.TH Susan Hollis, Wednesday Slow on [email protected], 520-825- 05/02/18 South Kaibab Trail -

Arizona State Trails

http://goo.gl/ClDvVC AZStatePparks.com/trails/trail_aztrail 580-5500 (623) Phone: AZStateParks.com/trails/trail_aztrail For more information, please visit: visit: please information, more For 85027-2929 AZ Phoenix, Avenue, 7th N. 21605 For more information, please visit: visit: please information, more For Hassayampa Field Office Office Field Hassayampa Indian Lands, and to drive Bulldog Canyon section. section. Canyon Bulldog drive to and Lands, Indian required to drive on state lands, in the Tonto Forest, on on Forest, Tonto the in lands, state on drive to required Arizona. Prescott, from miles 40 approximately County, www.aztrail.org/passages/passages December to May due to snow or flooding. A permit is is permit A flooding. or snow to due May to December Yavapai in located is trail the of end northern The Airport. at: found be can state the throughout open year-round, but in the north may be closed from from closed be may north the in but year-round, open Harbor Sky of north miles 40 approximately County, points access 43 the for South to North from maps The trail sections in the southern part of the state are are state the of part southern the in sections trail The Maricopa in located is trail the of end southern The Detailed passages. 43 into divided is Trail Arizona The How Can I Find This Trail? This Find I Can How Trail? This Find I Can How Trail? This Find I Can How AZStateParks.com/Trails/Trail_TopTrails inclusion into the “Top 100 Premier Trails”, please visit: visit: please Trails”, Premier 100 “Top the into inclusion To -

Grand Canyon National Park Media / Press Release

Media NEWS RELEASE Archived Press Releases Year 2005 Date Released Title 5-Dec-05 Woman Evacuated From Canyon After Fall From Mule 10-Nov-05 Final Environmental Impact Statement to Revise Colorado River Management Plan for Grand Canyon National Park Now Available 31-Oct-05 Final Environmental Impact Statement for Grand Canyon’s Colorado River Management Plan anticipated to be released within the next two weeks 28-Sept-05 AUTUMN COLORS PRELUDE NORTH RIM CLOSURE 26-Sept-05 Grand Canyon National Park to participate in National Parks America Tour 21-Sept-05 Body of man found in Grand Canyon identified 19-Sept-05 Missing Person Flyer - Randy Rogers 19-Sept-05 Update on Search Efforts for Phoenix Man Randy Rogers 16-Sept-05 Update on Search Efforts for Phoenix Man Randy Rogers 15-Sept-05 Search continues for Phoenix Man Randy Rogers 14-Sept-05 Park Rangers Continue Search for Randy Rogers 13-Sept-05 Park Rangers Searching for Missing Phoenix Man 13-Sept-05 Man’s body recovered from Grand Canyon 13-Sept-05 Park Rangers Locate Body Below the Rim of Grand Canyon 13-Sept-05 Agencies work together on pilot program to corral bison 12-Sept-05 Grand Canyon National Park, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and the Grand Canyon National Park Foundation celebrate National Public Lands Day with a weekend volunteer event 17-Aug-05 Fall from North Rim of Grand Canyon Results in Fatality 17-Aug-05 Yavapai Observation Station to close for rehabilitation and installation of exhibits 17-Aug-05 Construction to Begin on Market Plaza Shuttle Bus Stops in Grand -

History Along the Trail a Grand(View)

Canyon VIEWS Volume XXIIII, No. 2 JULY 2017 History Along the Trail A Grand(view) Adventure Black and White and Hidden from Sight The official nonprofit partner of Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon Association Canyon Views is published by the Grand Canyon FROM THE CEO Association, the National Park Service’s official nonprofit partner, raising private funds to “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning benefit Grand Canyon National Park, operating to find out going to the mountains is going home; that wilderness is a retail stores and visitor centers within the park and providing premier educational necessity.” opportunities about the natural and cultural history of Grand Canyon. John Muir, the great advocate for preserving our country’s wilderness, You can make a difference at Grand Canyon! wrote those words well over a century ago. Before the advent of For more information about GCA, please visit television. Before the 24-hour news cycle. Before the Internet and www.grandcanyon.org. social media. I can’t imagine what Muir would say about our world Board of Directors: Howard Weiner, Board today. But you can bet his remedy to counteract the “nerve-shaking” Chair; Mark Schiavoni, Board Vice Chair; Lyle we experience—probably 100 times worse now than in his day— Balenquah; Kathryn Campana; Richard Foudy; Eric Fraint; Teresa Gavigan; Robert Hostetler; would be the same. “Get out into nature,” he’d advise. Julie Klapstein; Teresa Kline; Kenneth Lamm; Marsha Sitterley; T. Paul Thomas There is truly nothing that helps us reset like spending time in wild Chief Executive Officer: Susan Schroeder places. -

Pocket Map South Rim Services Guide Grand Canyon

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Introduction to Backcountry Hiking Whether a day or overnight trip, hiking into Grand Canyon via Stay together, follow your plan, and know where and how to seek the Bright Angel, North Kaibab, or South Kaibab trails gives an help (call 911). Turning around may be the best decision. unparalleled experience that changes your perspective. For more information about Leave No Trace strategies, hiking Knowledge, preparation, and a good plan are all keys to tips, closures, roads, trails, and permits, visit go.nps.gov/grca- success. Be honest about your health and fitness, know your backcountry. limits, and avoid spontaneity—Grand Canyon is an extreme environment! Before You Go 10 Essentials for Your Day Pack • Each trail offers a unique opportunity to 1. WATER 6. SUN PROTECTION exprience Grand Canyon. Choose the Pack at least two liters of water depending Sunscreen, wide-brimmed hat, and appropropriate trail for your abilities. on hike intensity and duration. Always sunglasses. Consider walking the Rim Trail for an bring a water treatment method in case of easier experience. pipeline breaks or repair work. 7. COMMUNICATION Yelling, a whistle, signal mirrors, and cell • Check the weather forecast and adjust 2. FOOD phones—while service is limited, phones plans, especially to avoid summer heat. Salty snacks and high-calorie meal(s). can be helpful. Remember the weather can change suddenly. 3. FIRST AID KIT 8. EMERGENCY SHELTER A lightweight tarp provides shade and • Leave your itinerary with family or friends Include prescription medications, blister shelter.