Community Values for Southland's Freshwater Management Units

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Conversation with the Mayor Gary Tong

1 IN CONVERSATION WITH THE MAYOR GARY TONG through new technology (such as through our roading team’s use of drones). On a personal note, two things have stood have out this year; one of great sadness, the other a highlight. Sadly, we farewelled former Mayor Frana Cardno in April. She was a great role model and the reason I got into politics; a wonderful woman who will be sadly missed. Rest in peace, Frana. At the other end of the spectrum, in May I helped host His Mayor Gary Tong Royal Highness Prince Harry’s visit to Stewart Island. He’s a top bloke whose visit generated fantastic publicity for the Much like before crossing the road, island and Southland District. I’m sure our tourism industry at the end of each year I like to will see the benefi ts for some while yet. pause and look both ways. Just a few months ago the Southland Regional Development Strategy was launched. It gives direction for development of the region as a whole, with the primary focus on increasing our population. It tells us focusing on population growth will There’s a lot to look back on in 2015, and mean not only more people, it will provide economic growth, there’s plenty to come in 2016. Refl ecting on skilled workers, a better lifestyle, and improved health, the year that’s been, I realise just how much education and social services. We need to work together has happened in Southland District over the to achieve this; not just councils, but business, community, past year. -

FIORDLAND NATIONAL PARK 287 ( P311 ) © Lonely Planet Publications Planet Lonely ©

© Lonely Planet Publications 287 Fiordland National Park Fiordland National Park, the largest slice of the Te Wahipounamu-Southwest New Zealand World Heritage Area, is one of New Zealand’s finest outdoor treasures. At 12,523 sq km, Fiordland is the country’s largest park, and one of the largest in the world. It stretches from Martins Bay in the north to Te Waewae Bay in the south, and is bordered by the Tasman Sea on one side and a series of deep lakes on the other. In between are rugged ranges with sharp granite peaks and narrow valleys, 14 of New Zealand’s most beautiful fiords, and the country’s best collection of waterfalls. The rugged terrain, rainforest-like bush and abundant water have kept progress and people out of much of the park. Fiordland’s fringes are easily visited, but most of the park is impenetrable to all but the hardiest trampers, making it a true wilderness in every sense. The most intimate way to experience Fiordland is on foot. There are more than 500km of tracks, and more than 60 huts scattered along them. The most famous track in New Zealand is the Milford Track. Often labelled the ‘finest walk in the world’, the Milford is almost a pilgrimage to many Kiwis. Right from the beginning the Milford has been a highly regulated and commercial venture, and this has deterred some trampers. However, despite the high costs and the abundance of buildings on the manicured track, it’s still a wonderfully scenic tramp. There are many other tracks in Fiordland. -

Travel Report 2016-01-8-13 Tuatapere

8.1.2016 Tuatapere, Blue Cliffs Beach As we depart Lake Hauroko a big herd of sheep comes across our way. Due to our presence the sheep want to turn around immediately, but are forced to walk past us. The bravest sheep walks courageously in the front towards our car... Upon arriving in Tuatapere, the weather has changed completely. It is very windy and raining, so we decide to stop at the Cafe of the Last Light Lodge, which was very cozy and played funky music. Afterwards we head down to the rivermouth of the Waiau and despite the stormy weather Werner goes fishing. While we are parked there, three German tourists get stuck with their car next to us, the pebbles right next to the track are unexpectedly soft. Werner helps to push them out and we continue our way to the Blue Cliffs Beach – the sign has made us curious. We find a sheltered spot near the rivermouth so Werner can continue fishing. He comes back with an eel! Now we have to research eel recipes. 1 9.1.2016 Colac Bay, Riverton The very strong wind has blown away all the grey clouds and is pounding the waves against the beach. The rolling stones make such a noise, it’s hard to hear you own voice. Nature at work… Again we pass by the beautiful Red Hot Poker and finally have a chance to take a photo. We continue South on the 99, coming through Orepuki and Monkey Island. When the first settlers landed here a monkey supposedly helped to pull the boats ashore, hence the name Monkey Island. -

Full Article

NOTORNIS QUARTERLY JOURNAL of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand Volume Sixteen, Number Two, lune, 1969 NOTICE TO CONTRIBUTORS Contributions should be type-written, double- or treble-spaced, with a wide margin, on one side of the paper only. They should be addressed to the Editor, and are accepted o?, condition that sole publication is being offered in the first instance to Notornis." They should be concise, avoid repetition of facts already published, and should take full account of previous literature on the subject matter. The use of an appendix is recommended in certain cases where details and tables are preferably transferred out of the text. Long contributions should be provided with a brief summary at the start. Reprints: Twenty-five off-prints will be supplied free to authors, other than of Short Notes. When additional copies are required, these will be produced as reprints, and the whole number will be charged to the author by the printers. Arrangements for such reprints must be made directly between the author and the printers, Te Rau Press Ltd., P.O. Box 195, Gisborne, prior to publication. Tables: Lengthy and/or intricate tables will usually be reproduced photographically, so that every care should be taken that copy is correct in the first instance. The necessity to produce a second photographic plate could delay publication, and the author may be called upon to meet the additional cost. nlastrutions: Diagrams, etc., should be in Indian ink, preferably on tracing cloth, and the lines and lettering must be sufficiently bold to allow of reduction. Photographs must be suitable in shape to allow of reduction to 7" x 4", or 4" x 3f". -

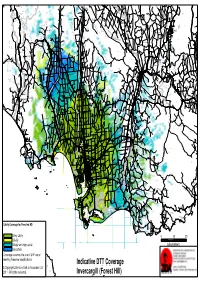

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1237 Measured South-Easterly, Generally, Along the Said State 2

30 APRIL NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1237 measured south-easterly, generally, along the said State 2. New Zealand Gazette, No. 35, dated 1 June 1967, page highway from Maria Street. 968. Situated within Southland District at Manapouri: 3. New Zealand Gazette, No. 26, dated 3 March 1983, page Manapouri-Hillside Road: from Waiau Street to a point 571. 500 metres measured easterly, generally, along the said road 4. New Zealand Gazette, No. 22, dated 25 February 1982, from Waiau Street. page 599. Manapouri-Te Anau Road: from Manapouri-Hillside Road to a 5. New Zealand Gazette, No. 94, dated 7 June 1984, page point 900 metres measured north-easterly, generally, along 1871. Manapouri-Te Anau Road from Manapouri-Hillside Road. 6. New Zealand Gazette, No. 20, dated 29 March 1962, page Situated within Southland District at Ohai: 519. No. 96 State Highway (Mataura-Tuatapere): from a point 7. New Zealand Gazette, No. 8, dated 19 February 1959, 250 metres measured south-westerly, generally, along the said page 174. State highway from Cottage Road to Duchess Street. 8. New Zealand Gazette, No. 40, dated 22 June 1961, page Situated within Southland District at Orawia: 887. No. 96 State Highway (Mataura-Tuatapere): from the south 9. New Zealand Gazette, No. 83, dated 23 October 1941, western end of the bridge over the Orauea River to a point 550 page 3288. metres measured south-westerly, generally, along the said 10. New Zealand Gazette, No.107, dated 21 June 1984, page State highway from the said end of the bridge over the Orauea 2277. River. -

Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197

SECTION 6 SCHEDULES Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 197 SECTION 6: SCHEDULES SCHEDULE SUBJECT MATTER RELEVANT SECTION PAGE 6.1 Designations and Requirements 3.13 Public Works 199 6.2 Reserves 208 6.3 Rivers and Streams requiring Esplanade Mechanisms 3.7 Financial and Reserve 215 Requirements 6.4 Roading Hierarchy 3.2 Transportation 217 6.5 Design Vehicles 3.2 Transportation 221 6.6 Parking and Access Layouts 3.2 Transportation 213 6.7 Vehicle Parking Requirements 3.2 Transportation 227 6.8 Archaeological Sites 3.4 Heritage 228 6.9 Registered Historic Buildings, Places and Sites 3.4 Heritage 251 6.10 Local Historic Significance (Unregistered) 3.4 Heritage 253 6.11 Sites of Natural or Unique Significance 3.4 Heritage 254 6.12 Significant Tree and Bush Stands 3.4 Heritage 255 6.13 Significant Geological Sites and Landforms 3.4 Heritage 258 6.14 Significant Wetland and Wildlife Habitats 3.4 Heritage 274 6.15 Amalgamated with Schedule 6.14 277 6.16 Information Requirements for Resource Consent 2.2 The Planning Process 278 Applications 6.17 Guidelines for Signs 4.5 Urban Resource Area 281 6.18 Airport Approach Vectors 3.2 Transportation 283 6.19 Waterbody Speed Limits and Reserved Areas 3.5 Water 284 6.20 Reserve Development Programme 3.7 Financial and Reserve 286 Requirements 6.21 Railway Sight Lines 3.2 Transportation 287 6.22 Edendale Dairy Plant Development Concept Plan 288 6.23 Stewart Island Industrial Area Concept Plan 293 6.24 Wilding Trees Maps 295 6.25 Te Anau Residential Zone B 298 6.26 Eweburn Resource Area 301 Southland District Plan Section 6 Schedules 27 June 2001 Page 198 6.1 DESIGNATIONS AND REQUIREMENTS This Schedule cross references with Section 3.13 at Page 124 Desig. -

Tuatapere-Community-Response-Plan

NTON Southland has NO Civil Defence sirens (fire brigade sirens are not used as warnings for a Civil Defence emergency) Tuatapere Community Response Plan 2018 If you’d like to become part of the Tuatapere Community Response Group Please email [email protected] Find more information on how you can be prepared for an emergency www.cdsouthland.nz Community Response Planning In the event of an emergency, communities may need to support themselves for up to 10 days before assistance arrives. The more prepared a community is, the more likely it is that the community will be able to look after themselves and others. This plan contains a short demographic description of Tuatapere, information about key hazards and risks, information about Community Emergency Hubs where the community can gather, and important contact information to help the community respond effectively. Members of the Tuatapere Community Response Group have developed the information contained in this plan and will be Emergency Management Southland’s first point of community contact in an emergency. Demographic details • Tuatapere is contained within the Southland District Council area; • The Tuatapere area has a population of approximately 1,940. Tuatapere has a population of about 558; • The main industries in the area include agriculture, forestry, sawmilling, fishing and transportation; • The town has a medical centre, ambulance, police and fire service. There are also fire stations at Orepuki and Blackmount; • There are two primary schools in the area. Waiau Area School and Hauroko Primary School, as well as various preschool options; • The broad geographic area for the Tuatapere Community Response Plan includes lower southwest Fiordland, Lake Hauroko, Lake Monowai, Blackmount, Cliften, Orepuki and Pahia, see the map below for a more detailed indication; • This is not to limit the area, but to give an indication of the extent of the geographic district. -

Southland Trail Notes Contents

22 October 2020 Southland trail notes Contents • Mararoa River Track • Tākitimu Track • Birchwood to Merrivale • Longwood Forest Track • Long Hilly Track • Tīhaka Beach Track • Oreti Beach Track • Invercargill to Bluff Mararoa River Track Route Trampers continuing on from the Mavora Walkway can walk south down and around the North Mavora Lake shore to the swingbridge across the Mararoa River at the lake’s outlet. From here the track is marked and sign-posted. It stays west of but proximate to the Mararoa River and then South Mavora Lake to this lake’s outlet where another swingbridge provides an alternative access point from Mavora Lakes Road. Beyond this swingbridge, the track continues down the true right side of the Mararoa River to a third and final swing bridge. Along the way a careful assessment is required: if the Mararoa River can be forded safely then Te Araroa Trampers can continue down the track on the true right side to the Kiwi Burn then either divert 1.5km to the Kiwi Burn Hut, or ford the Mararoa River and continue south on the true left bank. If the Mararoa is not fordable then Te Araroa trampers must cross the final swingbridge. Trampers can then continue down the true left bank on the riverside of the fence and, after 3km, rejoin the Te Araroa opposite the Kiwi Burn confluence. 1 Below the Kiwi Burn confluence, Te Araroa is marked with poles down the Mararoa’s true left bank. This is on the riverside of the fence all the way down to Wash Creek, some 16km distant. -

Fiordland Day Walks Te Wāhipounamu – South West New Zealand World Heritage Area

FIORDLAND SOUTHLAND Fiordland Day Walks Te Wāhipounamu – South West New Zealand World Heritage Area South West New Zealand is one of the great wilderness areas of the Southern Hemisphere. Known to Māori as Te Wāhipounamu (the place of greenstone), the South West New Zealand World Heritage Area incorporates Aoraki/Mount Cook, Westland Tai Poutini, Fiordland and Mount Aspiring national parks, covering 2.6 million hectares. World Heritage is a global concept that identifies natural and cultural sites of world significance, places so special that protecting them is of concern for all people. Some of the best examples of animals and plants once found on the ancient supercontinent Gondwana live in the World Heritage Area. Left: Lake Marian in Fiordland National Park. Photo: Henryk Welle Contents Fiordland National Park 3 Be prepared 4 History 5 Weather 6 Natural history 6 Formation ������������������������������������������������������� 7 Fiordland’s special birds 8 Marine life 10 Dogs and other pets 10 Te Rua-o-te-moko/Fiordland National Park Visitor Centre 11 Avalanches 11 Walks from the Milford Road Highway ����������������������������� 13 Walking tracks around Te Anau ����������� 21 Punanga Manu o Te Anau/ Te Anau Bird Sanctuary 28 Walks around Manapouri 31 Walking tracks around Monowai Lake, Borland and the Grebe valley ��������������� 37 Walking tracks around Lake Hauroko and the south coast 41 What else can I do in Fiordland National Park? 44 Contact us 46 ¯ Mi lfor d P S iop ound iota hi / )" Milford k r a ¯ P Mi lfor -

Southland Attractions

1 Cover art Tui by DEOW (Danny Owens) Magazine design Gloria Eno Produced by Southland District Council communications team ou’ve most probably seen his both his art and his technique, he says. spray paint. And then if I was only using work. Whether it’s a beautiful Y “I’ve turned it into a twist with New brushes there’s effects I couldn’t get with woman on a wall in a paddock, or brushes that I can with spray paint. a stunning mural in the city, you’ll Zealand heritage and the native birds recognise the graffiti art of New and my subject matter I’m working on “I think I’d be an idiot if I didn’t use Zealand’s southern-most graffiti artist, right now,” he says. “It could change - mixed media and different media to Danny “Deow” Owens. it might be cows next year or sheep the create what I’ve created.” year after.” Born in Invercargill, Deow has always Going from the raw rebellion of dabbled in art, but considers himself Deow enjoys painting birds and the his outdoor work to the relative self-taught. A year in California in challenges they pose to him as an artist. refinement of his native bird series is his mid-teens cemented his love for “Their features; their feet, their eyes, reflective of his journey as an artist. graffiti and started him on an “epic their feathers. It’s a content that’s “I haven’t forgotten the roots where I journey” that now sees him able to helped develop my art in general - the come from but it’s an image of where travel the world with his work. -

Short Walks 2 up April 11

a selection of Southland s short walks contents pg For the location of each walk see the centre page map on page 17 and 18. Introduction 1 Information 2 Track Symbols 3 1 Mavora Lakes 5 2 Piano Flat 6 3 Glenure Allan Reserve 7 4 Waikaka Way Walkway 8 5 Croydon Bush, Dolamore Park Scenic Reserves 9,10 6 Dunsdale Reserve 11 7 Forest Hill Scenic Reserve 12 8 Kamahi/Edendale Scenic Reserve 13 9 Seaward Downs Scenic Reserve 13 10 Kingswood Bush Scenic Reserve 14 11 Borland Nature Walk 14 12 Tuatapere Scenic Reserve 15 13 Alex McKenzie Park and Arboretum 15 14 Roundhill 16 Location of walks map 17,18 15 Mores Scenic Reserve 19,20 16 Taramea Bay Walkway 20 17 Sandy Point Domain 21-23 18 Invercargill Estuary Walkway 24 19 Invercargill Parks & Gardens 25 20 Greenpoint Reserve 26 21 Bluff Hill/Motupohue 27,28 22 Waituna Viewing Shelter 29 23 Waipapa Point 30 24 Waipohatu Recreation Area 31 25 Slope Point 32 26 Waikawa 32 27 Curio Bay 33 Wildlife viewing 34 Walks further afield 35 For more information 36 introduction to short Southland s walking tracks short walks Short walking tracks combine healthy exercise with the enjoyment of beautiful places. They take between 15 minutes and 4 hours to complete Southland is renowned for challenging tracks that are generally well formed and maintained venture into wild and rugged landscapes. Yet many of can be walked in sensible leisure footwear the region's most attractive places can be enjoyed in a are usually accessible throughout the year more leisurely way – without the need for tramping boots are suitable for most ages and fitness levels or heavy packs.