WA Template Final Draft 4-1-13.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socioeconomic Monitoring of the Olympic National Forest and Three Local Communities

NORTHWEST FOREST PLAN THE FIRST 10 YEARS (1994–2003) Socioeconomic Monitoring of the Olympic National Forest and Three Local Communities Lita P. Buttolph, William Kay, Susan Charnley, Cassandra Moseley, and Ellen M. Donoghue General Technical Report United States Forest Pacific Northwest PNW-GTR-679 Department of Service Research Station July 2006 Agriculture The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and National Grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all pro- grams.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Snowmobiles in the Wilderness

Snowmobiles in the Wilderness: You can help W a s h i n g t o n S t a t e P a r k s A necessary prohibition Join us in safeguarding winter recreation: Each year, more and more people are riding snowmobiles • When riding in a new area, obtain a map. into designated Wilderness areas, which is a concern for • Familiarize yourself with Wilderness land managers, the public and many snowmobile groups. boundaries, and don’t cross them. This may be happening for a variety of reasons: many • Carry the message to clubs, groups and friends. snowmobilers may not know where the Wilderness boundaries are or may not realize the area is closed. For more information about snowmobiling opportunities or Wilderness areas, please contact: Wilderness…a special place Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (360) 902-8500 Established by Congress through the Wilderness Washington State Snowmobile Association (800) 784-9772 Act of 1964, “Wilderness” is a special land designation North Cascades National Park (360) 854-7245 within national forests and certain other federal lands. Colville National Forest (509) 684-7000 These areas were designated so that an untouched Gifford Pinchot National Forest (360) 891-5000 area of our wild lands could be maintained in a natural Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest (425) 783-6000 state. Also, they were set aside as places where people Mt. Rainier National Park (877) 270-7155 could get away from the sights and sounds of modern Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest (509) 664-9200 civilization and where elements of our cultural history Olympic National Forest (360) 956-2402 could be preserved. -

Vaccinium Processing in the Washington Cascades

Joumul of Elhoobiology 22(1): 35--60 Summer 2002 VACCINIUM PROCESSING IN THE WASHINGTON CASCADES CHERYL A 1viACK and RICHARD H. McCLURE Heritage Program, Gifford Pirwhot National Forest, 2455 HighlL¥1lf 141, Dou! Lake, WA 98650 ABSTRACT,~Among Ihe native peoples of south-central Washington, berries of the genus Vaccil1ium hold a signHicant place among traditional foods. In the past, berries were collected in quantity at higher elevations in the central Cascade Mmmtains and processed for storage. Berries were dried along a shallow trench using indirect heat from d smoldering log. To date, archaeological investigations in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest have resulted in lhe identil1cation of 274 Vatcin;um drying features at 38 sites along the crest of the Cascades. Analyses have included archaeobotanical sampling,. radiocarbon dating. and identification of related features, incorporating ethnohistonc and ethnographic studies, Archae ological excavations have been conducted at one of the sites. Recent invesHgations indicate a correlation behveen high feature densities and specific plant commu nities in the mountain heml()(~k zone. The majority of the sites date from the historic period, but evidence 01 prehistoflc use is also indicated, Key words: berries, Vaccinium~ Cascade rv1ountains, ethnornstory, ardtaeubotanical record. RESUMEN,~-Entre los indig~.nas del centro-sur de Washinglon, las bayas del ge nero Vaccinium occupan un 1ugar significati''ilo entre los alirnentos tradicionales. En 121 pasado, estas bayas se recogfan en grandes canlidades en las zonas elevadas del centro de las rvtontanas de las Cascadas y se procesaban para e1 almacena miento, Las bayas Be secabl''ln n 10 largo de una zanja usando calor indirecto prod uddo POt un tronco en a"'icuas. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

2017-18 Olympic Peninsula Travel Planner

Welcome! Photo: John Gussman Photo: Explore Olympic National Park, hiking trails & scenic drives Connect Wildlife, local cuisine, art & native culture Relax Ocean beaches, waterfalls, hot springs & spas Play Kayak, hike, bicycle, fish, surf & beachcomb Learn Interpretive programs & museums Enjoy Local festivals, wine & cider tasting, Twilight BRITISH COLUMBIA VANCOUVER ISLAND BRITISH COLUMBIA IDAHO 5 Discover Olympic Peninsula magic 101 WASHINGTON from lush Olympic rain forests, wild ocean beaches, snow-capped 101 mountains, pristine lakes, salmon-spawning rivers and friendly 90 towns along the way. Explore this magical area and all it has to offer! 5 82 This planner contains highlights of the region. E R PACIFIC OCEAN PACIFIC I V A R U M B I Go to OlympicPeninsula.org to find more O L C OREGON details and to plan your itinerary. 84 1 Table of Contents Welcome .........................................................1 Table of Contents .............................................2 This is Olympic National Park ............................2 Olympic National Park ......................................4 Olympic National Forest ...................................5 Quinault Rain Forest & Kalaloch Beaches ...........6 Forks, La Push & Hoh Rain Forest .......................8 Twilight ..........................................................9 Strait of Juan de Fuca Nat’l Scenic Byway ........ 10 Joyce, Clallam Bay/Sekiu ................................ 10 Neah Bay/Cape Flattery .................................. 11 Port Angeles, Lake Crescent -

Layout 1 Copy 1

Events Contact Information Map and guide to points Festivals Goldendale From the lush, heavily forested April Earth Day Celebration – Chamber of Commerce of interest in and around Goldendale 903 East Broadway west side to the golden wheat May Fiddle Around the Stars Bluegrass 509 773-3400 W O Y L country in the east, Klickitat E L www.goldendalechamber.org L E Festival – Goldendale S F E G W N O June Spring Fest – White Salmon E L County offers a diverse selection Mt. Adams G R N O H E O July Trout Lake Festival of the Arts G J Chamber of Commerce Klickitat BICKLETON CAROUSEL July Community Days – Goldendale 1 Heritage Plaza, White Salmon STONEHENGE MEMORIAL of family activities and sight ~ Presby Quilt Show 509 493-3630 seeing opportunities. ~ Show & Shine Car Show www.mtadamschamber.com COUNTY July Nights in White Salmon City of Goldendale Wine-tasting, wildlife, outdoor Art & Fusion www.cityofgoldendale.com WASHINGTON Aug Maryhill Arts Festival sports, and breathtaking Sept Huckleberry Festival – Bingen Museums scenic beauty beckon visitors Dec I’m Dreaming of a White Salmon Carousel Museum–Bickleton Holiday Festival 509 896-2007 throughout the seasons. Y E L S Open May-Oct Thurs-Sun T E J O W W E G A SON R R Rodeos Gorge Heritage Museum D PETE O L N HAE E IC Y M L G May Goldendale High School Rodeo BLUEBIRDS IN BICKLETON 509 493-3228 HISTORIC RED HOUSE - GOLDENDALE June Aldercreek Pioneer Picnic and Open May-Sept Thurs-Sun Rodeo – Cleveland Maryhill Museum of Art June Ketcham Kalf Rodeo – Glenwood 509 773-3733 Aug Klickitat County Fair and Rodeo – Open Daily Mar 15-Nov 15 Goldendale www.maryhillmuseum.org Aug Cayuse Goldendale Jr. -

Chapter 3. Ecosystem Profile

CHAPTER 3. ECOSYSTEM PROFILE 3.1 Introduction This ecosystem profile has been prepared to provide a basis for understanding how watershed processes affect the form and function of Mason County’s shorelines. This chapter provides an overview of the watershed conditions across the landscape and describes how ecosystem-wide processes affect the function of the County’s shorelines as required under shoreline guidelines outlined in WAC 173-26- 210(3)(d). This watershed-scale overview provides context for the reach-scale discussion provided in Chapters 4 through 9. The landscape analysis approach to understanding and analyzing watershed processes developed by Stanley et al. (2005) has been referenced to complete this section of the report. Terms used in this section are defined in the document entitled Protecting Aquatic Ecosystems: A Guide for Puget Sound Planners to Understand Watershed Processes (Stanley et al., 2005). The maps referenced in this chapter are provided in Appendix A (Map Folio). Mason County is located generally in the southwestern corner of the Puget Sound Basin in western Washington. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Mason County has a total area of 1,051 square miles, of which 961 square miles is land and 90 square miles (8.6 percent) is water. Elevations in the County range from 6,400 feet above mean sea level (MSL) in the foothills of the Olympic Mountains, to sea level along the coastline of Puget Sound and Hood Canal. The County includes portions of five Water Resource Inventory Areas (WRIAs) as outlined below: • WRIA 14a: Kennedy Goldsborough; • WRIA 15: Kitsap; • WRIA 16/14b: Skokomish-Dosewallips and South Shore of Hood Canal; • WRIA 21: Queets-Quinault; and • WRIA 22: Lower Chehalis. -

Recreation Opportunity Guide

RECREATION OPPORTUNITY GUIDE Olympic National Forest http:/www.fs.usda.gov/olympic Recommended Season The Brothers Wilderness SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER Hood Canal Ranger District – Quilcene Office 295142 Highway 101 South P.O. Box 280 Quilcene, WA 98376 (360) 765-2200 OPPORTUNITIES: The Brothers Wilderness has excellent opportunities for backpacking, SIZE: 16,682 acres mountain climbing, hunting, hiking, camping, KEY ACCESS POINTS: and fishing. The Brothers Trail #821 begins at F.S. Road 25 (Hamma Hamma Rd.) the end of Lena Lake Trail #810 and provides F.S. Road 2510 (Duckabush Road) access to popular climbing routes to The Lena Lake Trail #810 Brothers. The trail is 3.0 miles in length and The Brothers Trail #821 ranges in difficulty from Easy to Difficult. The Duckabush Trail #803 Duckabush Trail #803 follows the Duckabush Mt. Jupiter Trail #809 River and enters the Olympic National Park in 6.2 miles and ranges from Easy to Difficult. The Mt. Jupiter Trail #809 is 7.9 miles in length and North FS Rd #2610 No Scale provides access along Jupiter Ridge to Jupiter Olympic THE Lakes. This trail is hot and dry during the National BROTHERS Olympic Park WILDERNESS National summer months and is considered Difficult. Forest Duckabush Trail #803 FS Rd #2510 Wilderness visitors should always carry rain gear The Brothers Hwy 101 and adequate clothing, food, and backpacking Trail #821 equipment. Proper boots and clothing should be Lena Lake FS Rd #25 worn. Practice LEAVE NO TRACE techniques Lena Lake Trail #810 during your wilderness trip. GENERAL DESCRIPTION: The Brothers TOPO MAPS: The Brothers USGS Quad or Wilderness is located on the east side of the The Brothers-Mt. -

TRAVERSING the BAILEY RANGE Solitude and Scenery on Olympic National Park’S Premier High Route

TRAVERSING THE BAILEY RANGE Solitude and scenery on Olympic National Park’s premier high route By Karl Forsgaard Deep in the northern wilderness of Olympic Na- tional Park, the Bailey Range Traverse crosses high, scenic country with grand views of surrounding river valleys and peaks—including 7,965-foot Mount Olympus. At each end of the traverse you’ll find popular trails – the Sol Duc River, Seven Lakes Basin and High Divide in the west, the Elwha River in the east. Be- tween those trails are several days of cross-country travel, re- quiring route-finding skills and mountaineering skills above and beyond basic backpack- ing. Good rock, snow and ice scrambling skills are essential. Sometimes you have to earn solitude: The Bailey Range Traverse in the Olympics When Bill and I started the is a rigorous combination of off-trail hiking, climbing, and snow-and-ice travel. trip in late July 2002, the up- But the views and loneliness are the payoffs. per Seven Lakes Basin was still mostly snow-covered, but east of Heart Lake earlier, so we were just the second regulations (including party size limits) the High Divide Trail and the Bailey party of the year. We did not see any apply. route above the Hoh had almost en- people on the off-trail part of the Day One: tirely melted out, so we rarely needed route . to use our ice axes (except in a few The traverse route is described Sol Duc River, Deer Lake snowfingers in creek gullies), and we in Climber’s Guide to the Olympic We left Seattle in two cars, took the never needed to use the crampons, Mountains by Olympic Mountain Bainbridge Island ferry and drove to rope or climbing hardware that we Rescue (Mountaineers, 1988) and in Port Angeles. -

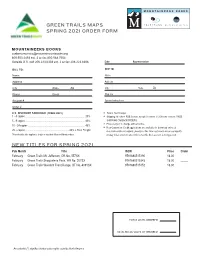

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

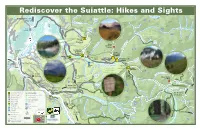

Rediscover the Suiattle: Hikes and Sights

Le Conte Chaval, Mountain Rediscover the Suiattle:Mount Hikes and Sights Su ia t t l e R o Crater To Marblemount, a d Lake Sentinel Old Guard Hwy 20 Peak Bi Buckindy, Peak g C reek Mount Misch, Lizard Mount (not Mountain official) Boulder Boat T Hurricane e Lake Peak Launch Rd na Crk s as C en r G L A C I E R T e e Ba P E A K k ch e l W I L D E R N E S S Agnes o Mountain r C Boulder r e Lake e Gunsight k k Peak e Cub Trailhead k e Dome e r Lake Peak Sinister Boundary e C Peak r Green Bridge Put-in C y e k Mountain c n u Lookout w r B o e D v Darrington i Huckleberry F R Ranger S Mountain Buck k R Green Station u Trailhead Creek a d Campground Mountain S 2 5 Trailhead Old-growth Suiattle in Rd Mounta r Saddle Bow Grove Guard een u Gr Downey Creek h Mountain Station lp u k Trailhead S e Bannock Cr e Mountain To I-5, C i r Darrington c l Seattle e U R C Gibson P H M er Sulphur S UL T N r S iv e uia ttle R Creek T e Falls R A k Campground I L R Mt Baker- Suiattle d Trailhead Sulphur Snoqualmie Box ! Mountain Sitting Mountain Bull National Forest Milk n Creek Mountain Old Sauk yo Creek an North Indigo Bridge C Trailhead To Suiattle Closure Lake Lime Miners Ridge White Road Mountain No Trail Chuck Access M Lookout Mountain M I i Plummer L l B O U L D E R Old Sauk k Mountain Rat K Image Universal C R I V E R Trap Meadow C Access Trail r Lake Suiattle Pass Mountain Crystal R e W I L D E R N E S S e E Pass N Trailhead Lake k Sa ort To Mountain E uk h S Meadow K R id Mountain T ive e White Chuck Loop Hwy ners Cre r R i ek R M d Bench A e Chuc Whit k River I I L Trailhead L A T R T Featured Trailheads Land Ownership S To Holden, E Other Trailheads National Wilderness Area R Stehekin Fire C Mountain Campgrounds National Forest I C Beaver C I F P A Fortress Boat Launch State Conservation Lake Pugh Mtn Mountain Trailhead Campground Other State Road Helmet Butte Old-growth Lakes Mt.