\ Preliminary Report on the Sheenjek River ( District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Yukon Hunting / Unit 25

Fort Yukon Hunting / Unit 25 $UFWLF9LOODJH &KDQGDODU :LVHPDQ &KULVWLDQ &ROGIRRW 9HQHWLH &KDON\LWVLN )RUW<XNRQ %HDYHU %LUFK&UHHN 6WHYHQV9LOODJH )RUW+DPOLQ &LUFOH &HQWUDO 5DPSDUW /LYHQJRRG &LUFOH+RW6SULQJV (XUHND 0LQWR )R[ &KHQD )$,5%$1.6 +RW (DJOH 6SULQJV Federal Public Lands Open to Subsistence Use 2014/2016 Federal Subsistence Wildlife Regulations 115 Unit 25 / Hunting (See Unit 25 Fort Yukon map) Unit 25 consists of the Yukon River drainage upstream from (but excluding) the Hamlin Creek drainage; and excluding drainages into the south bank of the Yukon River upstream from the Charley River. Unit 25A consists of the Hodzana River drainage rivers; and drainages into the north bank of the Yukon River upstream from the Narrows; the Chandalar River drainage upstream from Circle, including the islands in the Yukon upstream from (and including) the East Fork drainage; River. the Christian River drainage upstream from Christian; the Unit 25C consists of drainages into the south bank of Sheenjek River drainage upstream from (and including) the the Yukon River upstream from Circle to the Unit 20E Thluichohnjik Creek; the Coleen River drainage; and the boundary; the Birch Creek drainage upstream from the Old Crow River drainage. Steese Highway bridge (milepost 147); the Preacher Creek Unit 25B consists of the Little Black River drainage drainage upstream from (and including) the Rock Creek upstream from (but excluding) the Big Creek drainage; drainage; and the Beaver Creek drainage upstream from the Black River drainage upstream from (and including) (and including) the Moose Creek drainage. the Salmon Fork drainage; the Porcupine River drainage Unit 25D consists of the remainder of Unit 25. -

The Nationwide Rivers Inventory APPENDIX National System Components, Study Rivers and Physiographic Maps

The Nationwide Rivers Inventory APPENDIX National System Components, Study Rivers and Physiographic Maps The National Park Service United States Department of the Interior Washington, DC 20240 January 1982 III. Existing Components of the National System 1981 National Wild and Scenic Rivers System Components State Alaska 1 _ ** River Name County(s)* Segment Reach Agency Contact Description (mile1s) (s) Designation State Congressional Section(s) Length Date of District(s) Managing Physiographic Agency Alagnak River including AK I&W The Alagnak from 67 12/2/80 NPS National Park Service Nonvianuk Kukaklek Lake to West 540 West 5th Avenue boundary of T13S, R43W Anchorage, AK 99501 and the entire Nonvianuk River. Alntna River AK B.R. The main stem within the 83 12/2/80 NPS National Park Service Gates of the Arctic 540 West 5th Avenue National Park and Preserve. Anchorage, AK 99501 Andreafsky River and AK I614- Segment from its source, 262 12/2/80 FWS Fish and Wildlife Service East Fork including all headwaters 1011 E. Tudor and the East Fork, within Anchorage, AK 99503 the boundary of the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge. AK All of the river 69 12/2/80 NPS National Park Service Aniakchak River P.M. including its major 540 West 5th Avenue including: Hidden Creek tributaries, Hidden Creek, Anchorage, AK 99501 Mystery Creek, Albert Mystery Creek, Albert Johnson Creek, North Fork Johnson Creek, and North Aniakchak River Fork Aniakchak River, within the Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. *Alaska is organized by boroughs. If a river is in or partially in a borough, it is noted. -

Mineral Investigations in the Porcupine River Drainage, Alaska

MINERAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE PORCUPINE RIVER DRAINAGE, ALASKA By James C. Barker Alaska Field Operation Center, Fairbanks, Alaska * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Open File Report 27-81 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR James G. Watt, Secretary BUREAU OF MINES TN 23 .U44 8 1-27 UNITED STATES BUREAU OF MINES JAMES BOYD MEMORIAL LIBRARY FOREWORD This is one of a series of reports that present the findings of reconnaissance-type mineral assessments of certain lands in Alaska. It is important to remember that Alaska has not been seriously prospected for minerals other than gold--except in a few relatively limited areas. These reports include data developed by both contract and Bureau studies; frequently a combination of both. Assessing an area for its potential for buried mineral deposits is by far the most difficult of all natural resource assess- ments. This becomes more apparent when considering that no two deposits even of the same genesis and host rock conditions are identical. Moreover, judgments prior to drilling, the ultimate test, frequently vary among evaluators and continue to change as more detailed studies add to the understanding. Included in these reports are estimates of the relative favor- ability for discovering metalic and related nonmetallic mineral deposits similar to those mined elsewhere. Favorability is estimated by evaluation of visible outcrops, and analyses of sampling data, including mineralogic characteristics and associ- ated elements, in combination with an evaluation of the pro- cesses that have formed the rocks in which they occur. Essent- ially, it is a comparison of a related series of prospects and the environment in which they occur with the mineral deposits and environments in well-known mining districts. -

Wilderness Act 8

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Spring 2014 Fish & Wildlife News SPOTLIGHT 50 Years of The Wilderness Act 8 Refuge Therapy 24 Who Cares About Smoke 22 from the directorate Wilderness: Values Beyond Its Land Boundaries It’s hard for me to believe that it has been 20 years town were growing as bowhead whale carcasses from since I moved to Fairbanks, Alaska, to begin my the fall hunt were becoming a more important food assignment as manager of Arctic National Wildlife source and the sea ice receded farther and farther Refuge. The refuge is a world-class natural area and from shore. the preeminent remaining American wilderness. The experience changed my life; it deepened my As I was reflecting on my experiences in the Arctic understanding of the natural world and the human and the upcoming 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Jim Kurth experience in it. Act, I remember some words my friend Roger Kaye wrote about wilderness in Fulfilling the Promise, The place evokes a sense of timelessness. When you the 1999 document that set the path for the Refuge find fossilized coral on the refuge’s coastal plan, you System for the forthcoming decade: “Central to the can imagine the ancient ocean that once covered it. experience and awareness of wilderness is humility, Read current Arctic Billion-year-old rocks are exposed in the upthrust with its corollary, restraint; restraint in what is Refuge Manager of the Brooks Range. Muskoxen and caribou remind appropriate for visitors to do, as well as managers. Brian Glaspell’s take you that the Pleistocene Epoch—the Ice Age—was Restraint is the reason for the ‘minimum tool’ rule, on the refuge p. -

Fishery Management Plan Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge

FISHERY MANAGEMENT PLAN YUKON FLATS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Prepared By U.S Fish and Wildlife Service Fairbanks Fishery Assistance Office Fairbanks, Alaska April1990 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge Fishery. Management Plan Fairbanks Fishery Assistance Office Fairbanks, Alaska Aprill990 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables . iii List of Figures. .- .. iii Summary Statement . 1 I. Introduction . 2 II. General Physical and Biological Environment . 3 Physical Environment . 3 Biological Environment . 11 III. Fishery Resol;U'Ces . : .. 11 Spec1es I>esmpttons . 14 Habitat Descriptions . 14 Yukon River Tributaries . 14 Lake Habitat . 18 IV. Human Use and Management History . 20 Subsistence Fishing . 20 Commercial Fishing . 21 Recreational Use . 22 V. Issues and Concerns . 23 VI. Goals and Objectives . 25 VII. Strategies and Constraints . 26 Common Management Strategies . 26 Common Management Constraints . 27 Refuge Lake Management . 27 Refuge River and Stream Management . 27 VIII. Fishery Management Program . 30 IX. Priority of Tasks . 37 X. Bibliography . 41 Appendices . 43 Concurrence and Approval . 47 ii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Fish of the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge area 12 Table 2. Sonar counts of fall chum salmon, Sheenjek River, 1982-1986 . 16 Table 3. Fish species list and habitat preferences for Porcupine Drainage Complex . 17 Table 4. Estimated subsistence harvests of Yukon River salmon, Yukon Flats . 21 villages, 1986. Table 5. Yukon area commercial salmon catch and effort data, 1986 . 22 LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1. Location of the Yukon Flats Refuge . 3 Figure 2. Land status, Yukon Flats Refuge (October, 1985) . 5 Figure 3. Watersheds on the Yukon Flats Refuge . -

Porcupine River

draft wild and scenic river study february 1984 PORCUPINE RIVER ALASKA I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I DRAFT I WILD AND SCENIC RIVER STUDY I PORCUPINE RIVER ALASKA I I Abstract: The study finds that although the Porcupine River is eligible for the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, it is nonsuitable for inclusion. The report describes and evaluates four alternatives, I including the recommendation of no action. Comments: Comments on this draft study are invited from all interested parties and should be forwarded to the following official no later I than Regional Director I Alaska Regional Office National Park Service 2525 Gambell Street I Anchorage, Alaska 99503-2892 I I I I I I I U. S. Department of the Interior / National Park Service I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I" I I I. I I I I SUMMARY I Study of the Porcupine River to determine its eligibility and suitability for possible inclusion by Congress in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System was mandated in the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation I Act of December 2, 1980 (PL 96-487). The Porcupine River is a 472-mile-long free-flowing, unpolluted river that originates in Canada. The study area comprises the 212-mile segment I from the Canadian-U .S. border to its mouth on the Yukon River. This entire river segment is eligible for inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. -

Inventory and Cataloging of Interior Waters with Emphasis on the Upper Yukon and the Haul Road Areas

Volume 20 Study G-I-N STATE OF ALASKA Jay S. Hammond, Governor Annual Performance Report for INVENTORY AND CATALOGING OF INTERIOR WATERS WITH EMPHASIS ON THE UPPER YUKON AND THE HAUL ROAD AREAS Gary A. Pearse ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Ronald 0. Skoog, Commissioner SPORT FISH DIVISION Rupert E. Andreus, Director Job No. G-I-N Inventory and Cataloging of Interior Waters with Emphasis on the Upper Yukon and the Haul Road Areas By: Gary A. Pearse Abstract Background Sport Fish Catch and Effort General Drainage Description 1978 Field Studies Creel Census Lake Surveys Arctic Char Counts Purpose and Intent of Report Recommendations Koyukuk River Drainage Management Research Chandalar River Drinage Management Research Porcupine River Drainage Management Research Ob j ectives Techniques Used Findings Koyukuk River Drainage Chandalar River Drainage Porcupine River Drainage Annotated Bibliography Volume 20 Study No. G-I RESEARCH PROJECT SEGMENT State: ALASKA Name : Sport Fish Investigations of A1 as ka Project No.: F-9-11 Study No. : G- I Study Title: INVENTORY AND CATALOGING Job No. G- I-N Job Ti tle: -Inventory and Cataloging of Interior Waters with Emphasis on the Upper Yukon and the Haul Road Areas Period Covered: July 1, 1978 to June 30, 1979 'l'his report summarizes preliminary fisheries surveys conducted during the years 1964 through 1978 in a 106,190 square kilometer (41,000 square mile) study area in Northeastern Alaska. Area habitat, climate, and human activities are discussed, and sport and subsistence fishery uses are briefly described. A total of' 20 fish species was either captured or reported present. -

Alaska Interagency Coordination Center Situation Report Friday

Alaska Interagency Coordination Center Preparedness Level 1 Situation Report Friday - 07/17/2020 Wildland Fires New Out Active Merged YTD Fires YTD Acres Alaska Fire Service (AFS) 0 0 44 1 134 45,235.8 GAD (Galena Zone) 0 0 15 1 72 16,821.1 MID (Military) 0 0 0 0 1 1,285.1 TAD (Tanana Zone) 0 0 14 0 28 4,598.4 UYD (Upper Yukon Zone) 0 0 15 0 33 22,531.2 State of Alaska (DOF) 0 1 10 0 159 132,298.4 CRS (Copper River) 0 0 0 0 1 0.2 DAS (Delta) 0 0 0 0 8 22.3 FAS (Fairbanks) 0 0 1 0 19 52.8 KKS (Kenai) 0 1 4 0 44 20.3 MSS (AnchorageMatSu Area) 0 0 2 0 54 217.5 SWS (Southwest) 0 0 3 0 26 131,984.5 TAS (Tok) 0 0 0 0 7 0.8 Forest Service (USFS) 0 0 1 0 15 27.3 CGF (Chugach) 0 0 1 0 6 2.3 TNF (Tongass) 0 0 0 0 9 25.0 Statewide Totals 0 1 55 1 308 177,561.5 Active Wildfires: Protection Summary: CRI FUL MOD LIM NoEntry TOTAL AFS Protection: 1 4 9 31 0 45 DOF Protection: 4 3 0 3 0 10 USFS Protection: 0 0 0 1 0 1 Protection Totals: 5 7 9 35 0 56 Page 1 Friday 07/17/2020 Generated At: 8:47 Active Fires Status Summary Staffed Unstaffed Contained (S/C) Uncontained (S/U) Contained (U/C) Uncontained (U/U) AFS Protection: 0 1 7 35 DOF Protection: 0 0 5 5 USFS Protection: 0 0 0 1 Status Totals: 0 1 12 41 Active Fires Acreage Summary Acres Acreage Change 1 Staffed 16.0 0.0 54 Monitor 47,037.8 -88.9 1 Out 0.1 0.0 56 Fires Total Acres: 47,053.9 Prescribed Fires YTD Fires YTD Acres New Active Out Yesterday Military 2 79,945.0 0 0 0 National Park Service 1 19.3 0 0 0 Fuels Management Totals: 3 79,964.3 0 0 0 Cause Summary For All Fires (Includes Merged Fires -

Northeastern Alaska

Ui. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEt Field Library Albuquerque, New Mexica Reconnaissance for Radioactive Deposits Along the Upper Porcupine River, Northeastern Alaska Trace Elements Investigations Report 55 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY metadc3O46 i F s e . 1 e . - e a - 4 9 4s . * 1 4 4 1 a 0 4 * , s a - a1 1 e t 4- 5 4 UNJOLASSIIIED This doc-ument consists of 29 pages plus 2 maps.- series A CATEGORY III (Alaska) UNITED STATES DEPAED(1T 0F DIE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RECOINAI SSANCE POR RADIOACTIVE DEPOSITS ALONG TEE UPPER PORCUPINE RIVER, NORTEZA STERN ALASEA by Max G. White Juxne 1951 Trace Elements Investigations Report 55 2 USGS.-TZI REPORT 55 2he distribution (Series A) of this report iu as follows: 3 copies . ARC, Washington (JT. (G. Johnson) S copies . ARC, 1ev York (P. L. Merritt) I copy . ARC, Dearer, 0.1.. (C. C. Towle, Jr.) 1 copy . ARC, Spokane, Wash. (3. U. Thurlow) 1 copy . ARC, Orand Junction, Cole. (!. W. Outer) 1 copy . Territorial Department of Mines, Juneau, Alaska (L. I. Saarela) 1 copy . Territorial Department of Mines Assay Office, Anchorage, Alaska (J. J. O'Shea) 1 copy . ... Territorial Department of Mines Assay Office, College, Alaska (D. J. Cook) 1 copy . ... Territorial Department of Mines Assay Office, Ketchikan, Alaska (A. 3. Glover) 1 copy . ... Territorial Department of Mines Assay Office, lome, Alaska (D. A. Jones) 9 copies . USGS, Washington (Mineral Deposits Branch) copy . .. USGS, Washington (Geochemistry and Petrolog Branch) copy ... USGS, Washington (?u..ls Branch) 5 copies . USGS, Wshiagton (Alaskan Branch) copy . USGS, Washington (Geopbysics Brach) copy . -

Sheenjek River Salmon Escapement Enumeration, 1986

AYK Region Yukon Salmon Escapement Report No. 33 Sheenjek River Salmon Escapement Enumeration, 1986 Prepared by Louis H. Barton Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Commercial Fisheries Fairbanks, Alaska December 1987 Table of Contents List of Tables. ; List of Figures i List of Appendix Tables i i Abstract. iii Introduction. 1 Study Area. 1 Objectives. 2 Materials and Methods 2 Results and Discussion. 5 Timing • 5 Abundance. 11 Age, Sex, and Size Composition 14 Summary . 18 Conclusions 18 Recommendations 19 Literature Cited. 19 i list of Tables Table 1. Adjusted east and west bank sonar counts and estimated number of salmon passing the sonar site in midstream in the Sheenjek River, 17 August-24 September, 1986. • 12 Table 2. Mean length at age (by sex} of fall chum salmon sampled in the Sheenjek River in 1986. • . • • • • • • • • • . 15 Table 3. Comparative age composition of Sheenjek River fall chum salmon escapements, 1974-1986. • •.••.. 17' list of Figures Page Figure 1. Sheenjek River drainage. 3 Figure 2. Sheenjek River project site. 4 Figure 3. Sheenjek River depth profile at the sonar counting site on 17 August 1986 •..•••.•.••.. 6 Figure 4. Water level fluctuations, surface temperatures, and surface velocities at the Sheenjek River project site from 18 August through 24 September 1986. .. fll • 7 Figure 5. Fall chum salmon escapement timing in the Sheenjek River, 1981-1986 •.••••••••••..•• 9 Figure 6. Average migration (percent) of Sheenjek River fall chum salmon past the sonar site by time of day from 17 August through 24 September 1986 •• 10 Figure 7. Length-frequency distributions by sex and age group of SheenJek River fall chum salmon sampled in 1986. -

Environmental and Cultural Overview of the Yukon Flats Region Prepared By: Kevin Bailey, USFWS Archaeologist Date: 2/12/2015 In

Environmental and Cultural Overview of the Yukon Flats Region Prepared by: Kevin Bailey, USFWS Archaeologist Date: 2/12/2015 Introduction With a substantial population of Native people residing in their traditional homeland and living a modern traditional lifestyle, the Yukon Flats Refuge and all of the Alaskan Interior is a dynamic and living cultural landscape. The land, people, and wildlife form a tight, interrelated web of relationships extending thousands of years into the past. Natural features and human created “sites” form a landscape of meaning to the modern residents. The places and their meanings are highly relevant to modern residents, not just for people and culture but for the land. To many Gwich’in people culture is not distinct from their homeland. Although only minimally discussed in this overview, this dynamic living cultural landscape should be considered and discussed when writing about this area. Environmental Setting Containing the largest interior basin in Alaska, the Yukon Flats Refuge encompasses over 11 million acres of land in east central Alaska. Extending roughly 220 miles east-west along the Arctic Circle, the refuge lies between the Brooks Range to the north, and the White-Crazy Mountains to the south. The pipeline corridor runs along the refuge’s western boundary while the eastern boundary extends within 30 miles of the Canadian border. The Yukon River bisects the refuge, creating the dominant terrain. As many as 40,000 lakes, ponds, and streams may occur on the refuge, most concentrated in the flood plain along the Yukon and other rivers. Upland terrain, where lakes are less abundant, is the source of important drainage systems. -

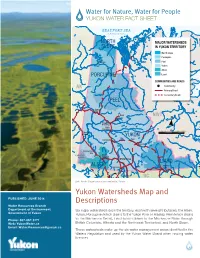

Yukon Watersheds Map and Descriptions

Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET Left: North Slope tundra and wetlands, Yukon Yukon Watersheds Map and PUBLISHED: JUNE 2014 Descriptions Water Resources Branch Department of Environment Six major watersheds drain the territory, each with several tributaries: the Alsek, Government of Yukon Yukon, Porcupine (which drains to the Yukon River in Alaska), Peel (which drains to the Mackenzie Delta), Liard (which drains to the Mackenzie Basin through Phone: 867-667-3171 Web: YukonWater.ca British Columbia, Alberta and the Northwest Territories), and North Slope. Email: [email protected] These watersheds make up the six water management areas identified in the Waters Regulation and used by the Yukon Water Board when issuing water licences. 1 Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET City of Whitehorse, and Yukon River Yukon River Basin (including the Alsek River Basin Porcupine River Basin) The Alsek River drains the southwestern portion of the Yukon to the Pacific Ocean. It is classified as a The Yukon River Headwaters contains the Southern Canadian Heritage River because of its significant Lakes region of Yukon and Northern British Columbia; natural resources: massive ice fields, high mountain there are glaciers throughout the mountains of these peaks, unique geologic history, coastal and interior headwaters. The Teslin River joins the Yukon River plant communities, significant grizzly bear population, north of Lake Laberge, contributing water mainly from and diverse bird species. snowmelt runoff in the upper portions of the basin. The Pelly and Stewart Rivers drain the eastern portion of the drainage, including mountainous terrain.