Physiological Responses of the Australian Cattle Dog to Mustering Exercise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Levels 1/2/3/4/5/C

Running Order for: Saturday February 13, 2010 Queen City Agility Club Ring 1 FullHouse Round 1 - Levels 1/2/3/4/5/C Jump Ht Armband Call Name Breed Level Owner/Handler 4 4001 Schnitzel Dachshund 3 Christi & Maria O'Brien 8021 T Spriggan Cairn Terrier 1 Jennifer Stuckey 12027 S Spooky Miniature Schnauzer 5 Brenda Gilday 8022 V Banshee Norwich Terrier 5 Jennifer Stuckey 8024 V Bette Lyn All American 5 Judith & Bobby Ray 8025 V Whisper Papillon 2 Cheryl & Ivan Immel 8 8001 Diva Welsh Corgi (Pembroke) 4 Jane Dewey 8018 Magic Papillon 3 Cheryl & Ivan Immel 8015 Kovey Miniature Schnauzer 1 Carole Lenehan 8003 Frazier West Highland White Terrier 2 Gwen Lewis 8004 Spencer Chihuahua 5 Brenda Russell 8006 Daisy Cavalier King Charles Spaniel 5 Darlene & Robert Miller 8007 Bella Miniature Schnauzer C Brenda Gilday 8008 Tasha American Eskimo Dog 5 Tammy Powers 8009 Ripley All American 3 Kevin & Marianne Reynolds 8013 Yoda All American C J Kristin Aeh 8014 Snoopy Dachshund 4 Cheryl Holman 8002 Nelson Welsh Corgi (Pembroke) 2 Jane Dewey 8005 Emma Chihuahua 4 Brenda Russell 8016 Twisty Miniature Schnauzer 4 Carole Lenehan 8017 Jack Havanese 2 Susan Perry 8019 Lacey Papillon 2 Cheryl & Ivan Immel 12020 T Sissey Shetland Sheepdog 2 MaryAnn Chappelear 12021 V Cory Cocker Spaniel 5 Janne Farrell 12023 V Annabelle American Cocker Spaniel C Kay Rife 12024 V Zipo Poodle (Miniature) 2 Kim McMahan 12 12001 Kinsey Shetland Sheepdog 4 MaryAnn Chappelear 12006 Charm Rat Terrier 4 Katherine & Forrest Meyer 12016 Rudy Miniature Pinscher 1 Mary Meno 12007 Taffee American -

Agtsec Running Groups

Group A - 142 competitors Champ: 10 - 8, 14 - 5, 16 - 12, 20 - 15, 22 - 18, 24 - 12 Perf: P8 - 9, P12 - 6, P14 - 8, P16 - 10, P20 - 9 Vet: V4 - 4, V8 - 5, V12 - 17, V16 - 4 Addison, Michelle DeChance, Annie Lady (24) German Shepherd Dog Pink Floyd (V12) Token Blonde Spencer Davis (P20) Rico Suave Dog Alfonso, Annette Chapter (22) Border Collie Erspamer, Mia Legend (V12) Border Collie Jackson (P20) Labrador Retriever Valid (P20) Border Collie Anderson, Cliff Zoe (20) Wheatable Ferguson, Kelley Winnie (V12) Border Collie Joose (16) Border Collie Anderson, Crystal Floyd, Cindy Razzi (P14) English Springer Spaniel Thor (16) Poodle (Miniature) Andrews, Lisa Friedl, Gwyneth Shibumi (24) Border Collie Amigo (24) Border Collie Aubois, Sara Gant, Shane Ridley (P20) Border Collie Atom (P20) Border Collie Sweets (P12) Shetland Sheepdog Barton, Kim Logan (V 4) Shih Tzu Garcia, Allison EPI (20) All-American Sizzle (V 8) Shetland Sheepdog Better Cheddar (14) All-American Bekaert, Susan Ringer (P16) Border Collie ABBA (V12) Border Collie Motown (16) Shetland Sheepdog Garvey, Sarah Poppy (24) All-American Bennett, Alicia Excalibur (V16) Border Collie Gerhard, Jeremy Bleu (10) Papillon Maverick (10) Pembroke Welsh Corgi Pixie Pig (20) Border Collie Tease (20) Border Collie Ruckus (22) Australian Shepherd Benson, Helen Shadow (16) Shetland Sheepdog Grace, Kathy Blanche (16) Standard Schnauzer Bowman, Tom Casey (P14) All-American Hanson, Morgan Probability (P16) Border Collie Brown, Kat #Winning (22) Border Collie Nemo (P14) All-American Elite (20) Border -

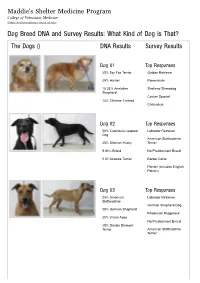

Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog Is That? the Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results

Maddie's Shelter Medicine Program College of Veterinary Medicine (https://sheltermedicine.vetmed.ufl.edu) Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog is That? The Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results Dog 01 Top Responses 25% Toy Fox Terrier Golden Retriever 25% Harrier Pomeranian 15.33% Anatolian Shetland Sheepdog Shepherd Cocker Spaniel 14% Chinese Crested Chihuahua Dog 02 Top Responses 50% Catahoula Leopard Labrador Retriever Dog American Staffordshire 25% Siberian Husky Terrier 9.94% Briard No Predominant Breed 5.07 Airedale Terrier Border Collie Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 03 Top Responses 25% American Labrador Retriever Staffordshire German Shepherd Dog 25% German Shepherd Rhodesian Ridgeback 25% Lhasa Apso No Predominant Breed 25% Dandie Dinmont Terrier American Staffordshire Terrier Dog 04 Top Responses 25% Border Collie Wheaten Terrier, Soft Coated 25% Tibetan Spaniel Bearded Collie 12.02% Catahoula Leopard Dog Briard 9.28% Shiba Inu Cairn Terrier Tibetan Terrier Dog 05 Top Responses 25% Miniature Pinscher Australian Cattle Dog 25% Great Pyrenees German Shorthaired Pointer 10.79% Afghan Hound Pointer (includes English 10.09% Nova Scotia Duck Pointer) Tolling Retriever Border Collie No Predominant Breed Dog 06 Top Responses 50% American Foxhound Beagle 50% Beagle Foxhound (including American, English, Treeing Walker Coonhound) Harrier Black and Tan Coonhound Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 07 Top Responses 25% Irish Water Spaniel Labrador Retriever 25% Siberian Husky American Staffordshire Terrier 25% Boston -

Objectives Main Menu Herding Dogs Herding Dogs

12/13/2016 Objectives • To examine the popular species of companion dogs. • To identify the characteristics of common companion dog breeds. • To understand which breeds are appropriate for different settings and uses. 1 2 Main Menu • Herding • Working • Hound Herding Dogs • Sporting • Non-Sporting • Terrier • Toy 3 4 Herding Dogs Herding Dogs • Are born with the instinct to control the • Include the following breeds: movement of animals −Australian Cattle Dog (Blue or Red Heeler) −Australian Shepherd −Collie −Border Collie −German Shepherd −Old English Sheepdog −Shetland Sheepdog −Pyrenean Shepard −Welsh Corgi, Cardigan −Welsh Corgi, Pembroke 5 6 1 12/13/2016 Australian Cattle Dogs Australian Cattle Dog Behavior • Weigh 35 to 45 pounds and • Is characterized by the measure 46 to 51 inches tall following: • Grow short to medium length −alert straight hair which can be −devoted blue, blue merle or red merle −intelligent −loyal in color −powerful • Are born white and gain their −affectionate color within a few weeks −protective of family, home and territory −generally not social with other pets 7 8 Australian Shepherds Australian Shepherds • Males weigh 50 to 65 pounds and measure • Have a natural or docked bobtail 20 to 23 inches in height • Possess blue, amber, hazel, brown or a • Females weigh 40 to 55 pounds and combination eye color measure 18 to 21 inches in height • Grow moderate length hair which can be black, blue merle, red or red merle in color 9 10 Australian Shepherd Behavior Collies • Is characterized by the following: • Weigh -

Commencing Implementation of a Genetic Evaluation System for Livestock Working Dogs by C

Commencing implementation of a genetic evaluation system for livestock working dogs by C. M. Wade, D. van Rooy, E. R. Arnott, J. B. Early and P. D. McGreevy June 2021 Commencing implementation of a genetic evaluation system for livestock working dogs by C. M. Wade, D. van Rooy, E. R. Arnott, J. B. Early and P. D. McGreevy June 2021 i © 2021 AgriFutures Australia All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-76053-135-5 ISSN 1440-6845 Commencing implementation of a genetic evaluation for livestock working dogs Publication No. 20-117 Project No: PRJ-010413 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, AgriFutures Australia, the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, AgriFutures Australia, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

Texas Herding Association AKC Trial & Tests October 2,3,4 2020 Destiny

Texas Herding Association AKC Trial & Tests October 2,3,4 2020 Destiny Farm, Bertram TX Friday 10/2/2020 - Trial 1 Course: D - Sheep Judge: Stacey Edwards Intermediate Place Armband Dog Breed Owner Handler Result Score Time 1 301 Ripple Australian Cattle Dog Sherry Clark Sherry Clark Q 79 20:53.00 Advanced Ties broken by best score on outrun, then time. Place Armband Dog Breed Owner Handler Result Score Time Tie breaker 1/H 103 Rey Border Collie Sherry Clark Sherry Clark Q 84 14:59.00 Carolynn Cobb 2/R 102 Trips Berger Picard Susan Frensley Pat Taylor Q 82 15:54.00 8.0 Michele McGuire 3 101 Cody Border Collie Michal Bagley Michal Bagley Q 82 16:29.00 7.0 4 104 Will Border Collie Mary Carter Mary Carter Q 81 12:20.00 Friday 10/2/2020 - Trial 2 Course: D - Sheep Judge: Kirsten Cole-MacMurray Intermediate Place Armband Dog Breed Owner Handler Result Score Time 1 601 Tuff Border Collie Diane Vercher Diane Vercher Q 81 12:36.00 2 602 Ripple Australian Cattle Dog Sherry Clark Sherry Clark Q 75 12:37.00 Advanced Place Armband Dog Breed Owner Handler Result Score Time 1/H 404 Cody Border Collie Michal Bagley Michal Bagley Q 86.5 13:43.00 Carolynn Cobb 2/R 403 Trips Berger Picard Susan Frensley Pat Taylor Q 83.5 13:24.00 Michele McGuire 3 401 Will Border Collie Mary Carter Mary Carter Q 79.5 13:30.00 402 Rey Border Collie Sherry Clark Sherry Clark NQ Texas Herding Association AKC Trial & Tests October 2,3,4 2020 Destiny Farm, Bertram TX Friday 10/2/2020 - Trial 3 Course: D - Sheep Judge: Stacey Edwards Intermediate Place Armband Dog Breed Owner -

Estimating the Economic Value of Australian Stock Herding Dogs

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 5-2014 Estimating the Economic Value of Australian Stock Herding Dogs E. R. Arnott University of Sydney J. B. Early University of Sydney C. M. Wade University of Sydney P. D. McGreevy University of Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/spwawel Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Arnott, E. R., Early, J. B., Wade, C. M., & McGreevy, P. D. (2014). Estimating the economic value of Australian stock herding dogs. Animal Welfare, 23(2), 189-197. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Estimating the Economic Value of Australian Stock Herding Dogs ER Amott, JB Early, CM Wade and PD McGreevy University of Sydney KEYWORDS animal welfare, canine value, farm economics, owner survey, stock herding, working dog ABSTRACT This study aimed to estimate the value of the typical Australian herding dog in terms of predicted return on investment. This required an assessment of the costs associated with owning herding dogs and estimation of the work they typically perform. Data on a total of 4,027 dogs were acquired through The Farm Dog Survey which gathered information from 812 herding dog owners around Australia. The median cost involved in owning a herding dog was estimated to be a total of AU$7,763 over the period of its working life. The work performed by the dog throughout this time was estimated to have a median value of AU$40,000. -

Best Stock Dog Breeds a Recent Poll Indicates Top Five Breeds Recommended for Use As a Stock Dog in the United States

March 2013 95 Stock dog series: Part II Best Stock Dog Breeds A recent poll indicates top five breeds recommended for use as a stock dog in the United States. Story by Typically ranging from 25 lb. to 55 lb., These dogs are known as gathering or KELLI FULKERSON they sport coats of medium texture and herding-type dogs that can wind and trail wavy hair. Their colors are blue merle, red cattle. Their appearance must be slick hair merle, solid black and solid red. Another and bobbed tail. Their colors vary from Soon-to-be dog owners frequently distinct characteristic is the butterfly nose. black, red or merle, to multi-colored. ask, “What breed will work best for Meier says the most distinct cattle?” says Deb Meier, editor of The characteristic of an Australian Shepherd is Registration Stockdog Journal. To some breed-specific companionship with its herd, as well as its In the cattle industry, breed registration enthusiasts, this question may seem master. Australian Shepherds are versatile is a highly recommended and desired offensive. However, the diversity and and easily trained, performing tasks with tool for the success and integrity of an PHOTOS BY MARY BLOOM © AKC BLOOM MARY BY PHOTOS management of cattle operations are Australian Cattle Dog style and enthusiasm. operation. This also rings true in the determining factors in what breed of dog canine industry, says Meier. The stock-dog will be best for a particular situation. known as heelers because of their industry has varying opinions about the Recently, research at South Dakota instinctive grip, says the Australian best registry for your stock dog. -

A Guide to the Livestock-Working

A Guide to the $1.50 Livestock-working Dog B. Henny elcome to the Selecting Your fascinating world Wof the livestock- Employee working dog. This publication If you select and train contains four sections: your working dog as carefully • Selecting the working dog, as you would hire and train a including review of the manager for your farm, you common working breeds can have a very valuable four- legged employee that does the • Basic training methods work of four people and and tips becomes your best and most • The International Sheep Dog faithful friend. Whether you select honest. List your Rules with course pattern and train the dog yourself, or traits, such as • A list of resources including instruct a 4-H member, we can’t temper, patience, and breed associations overemphasize the importance of the type of discipline you use. studying all aspects of training Don’t be afraid or too vain to ask It’s intended as a reference before you begin. your spouse, parents, or leader if guide, not a training manual. The first thing to consider is the list accurately reflects your “Training a working dog is not choosing the working breed most personality. Then study the breeds child’s play. It is serious business, suited to your personality and and make a selection that suits you. requiring patience, perseverance, situation. Each working breed has The following is a review of the and knowledge of what you want common personality traits and a most common working breeds and your dog to learn. You must not primary purpose for which it was some helpful hints on the “non- expect the dog to learn it all in a bred. -

A Rangeland Parable

A Rangeland Parable Item Type text; Article Authors Nelle, Steve Citation Nelle, S. (1981). A Rangeland Parable. Rangelands, 3(6), 238. Publisher Society for Range Management Journal Rangelands Rights Copyright © Society for Range Management. Download date 30/09/2021 12:00:14 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/638314 238 Rangelands 3(6), December 1981 literature summarized as follows. I would consider any and Longton, Tim, and Edward Hart. 1976. The sheep dog: Its all of the books valuable to the stock dog owner and/or work and training. Davis and Charles, Inc. North Pomfret, trainer. Vermont 05053. USA. 124 p. Allen, Arthur N. 1965. Border collies in America. Arthur N. This book is written primarily for the Border collie in sheep work. Itincludes much information on train- Rt. Illinois 62859. USA. 56 dog management, Allen, 3, McLeansboro, p. ing, and trialing. An excellent book. This book contains much academic information on Bordercol- lies as well as for on the ranch and in training sheep handling Ben. 1970. Rt. trials.' It is easyto read withclear informative pictures. A good Means, The perfect stock dog. Ben Means, 1, book. Box 23, Walnut Grove, Missouri 65770. 24 p. This book iswritten primarily for training of the Bordercollie for Author not stated. No date. of Australia. official farm and ranch workwithout consideration for trialing, etc. It Dogs (An has a few and and iswritten the Kennel Control Council. Victo- pictured diagrammedillustrations publication of Melborne, in the language of the country boy with special emphasis on ria.) Humphrey & Formula Press. -

Juniors & Intermediates Herding Powerpoint

Updated – Jan. 2021 Herding Group Junior & Intermediates Height: 18-20 inches (male), 17-19 inches (female) Weight: 35-50 pounds Life Expectancy: 12-16 years AUSTRALIAN CATTLE DOG HERDING Height: 20-23 inches (male), 18-21 inches (female) Weight: 50-65 pounds (male), 40-55 pounds (female) Life Expectancy: 12-15 years Photos Compliments of A.K.C. AUSTRALIAN SHEPHERD HERDING Height: 21-22 inches (male), 20-21 inches (female) Weight: 45-55 pounds Life Expectancy: 12-14 years Photos Compliments of A.K.C. BEARDED COLLIE HERDING Height: 24-26 inches (male), 22-24 inches (female) Weight: 60-80 pounds (male), 40-60 pounds (female) Life Expectancy: 14-16 years Photos Compliments of A.K.C. BELGIAN MALINOIS HERDING Height: 19-22 inches (male), 18-21 inches (female) Weight: 30-55 pounds Life Expectancy: 12-15 years Photos Compliments of A.K.C. BORDER COLLIE HERDING Height: 20-24 inches (male), 19-23 inches (female) Weight: 45-55 pounds (male), 35-45 pounds (female) Life Expectancy: 12-15 years Photos Compliments of A.K.C. CANAAN DOG HERDING Height: 10.5-12.5 inches Weight: 30-38 pounds (male), 25-34 pounds (female) Life Expectancy: 12-15 years Photos Compliments of A.K.C. CARDIGAN WELSH CORGI HERDING Height: 24-26 inches (male), 22-24 inches (female) Weight: 60-75 pounds (male), 50-65 pounds (female) Life Expectancy: 12-14 years Photos Compliments of A.K.C. COLLIE HERDING Height: 24-26 inches (male), 22-24 inches (female) Weight: 65-90 pounds (male), 50-70 pounds (female) Life Expectancy: 12-14 years Photos Compliments of A.K.C.