CHAPTER 12. Human Impacts on Narragansett Bay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tidal Flushing and Eddy Shedding in Mount Hope Bay and Narragansett Bay: an Application of FVCOM

Tidal Flushing and Eddy Shedding in Mount Hope Bay and Narragansett Bay: An Application of FVCOM Liuzhi Zhao, Changsheng Chen and Geoff Cowles The School for Marine Science and Technology University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth 706 South Rodney French Blvd., New Bedford, MA 02744. Corresponding author: Liuzhi Zhao, E-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract The tidal motion in Mt. Hope Bay (MHB) and Narragansett Bay (NB) is simulated using the unstructured grid, finite-volume coastal ocean model (FVCOM). With an accurate geometric representation of irregular coastlines and islands and sufficiently high horizontal resolution in narrow channels, FVCOM provides an accurate simulation of the tidal wave in the bays and also resolves the strong tidal flushing processes in the narrow channels of MHB-NB. Eddy shedding is predicted on the lee side of these channels due to current separation during both flood and ebb tides. There is a significant interaction in the tidal flushing process between MHB-NB channel and MHB-Sakonnet River (SR) channel. As a result, the phase of water transport in the MHB-SR channel leads the MHB-NB channel by 90o. The residual flow field in the MHB and NB features multiple eddies formed around headlands, convex and concave coastline regions, islands, channel exits and river mouths. The formation of these eddies are mainly due to the current separation either at the tip of the coastlines or asymmetric tidal flushing in narrow channels or passages. Process-oriented modeling experiments show that horizontal resolution plays a critical role in resolving the asymmetric tidal flushing process through narrow passages. -

View Strategic Plan

SURGING TOWARD 2026 A STRATEGIC PLAN Strategic Plan / introduction • 1 One valley… One history… One environment… All powered by the Blackstone River watershed and so remarkably intact it became the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor. SURGING TOWARD 2026 A STRATEGIC PLAN CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................ 2 Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor, Inc. (BHC), ................................................ 3 Our Portfolio is the Corridor ............................ 3 We Work With and Through Partners ................ 6 We Imagine the Possibilities .............................. 7 Surging Toward 2026 .............................................. 8 BHC’s Integrated Approach ................................ 8 Assessment: Strengths & Weaknesses, Challenges & Opportunities .............................. 8 The Vision ......................................................... 13 Strategies to Achieve the Vision ................... 14 Board of directorS Action Steps ................................................. 16 Michael d. cassidy, chair Appendices: richard gregory, Vice chair A. Timeline ........................................................ 18 Harry t. Whitin, Vice chair B. List of Planning Documents .......................... 20 todd Helwig, Secretary gary furtado, treasurer C. Comprehensive List of Strategies donna M. Williams, immediate Past chair from Committees ......................................... 20 Joseph Barbato robert Billington Justine Brewer Copyright -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

For the Conditionally Approved Lower Providence River Conditional Area E

State of Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Office of Water Resources Conditional Area Management Plan (CAMP) for the Conditionally Approved Lower Providence River Conditional Area E May 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents i List of Figures ii List of Tables ii Preface iii A. Understanding and Commitment to the Conditions by all Authorities 1 B. Providence River Conditional Area 3 1. General Description of the Growing Area 3 2. Size of GA16 10 3. Legal Description of Providence River (GA 16): 11 4. Growing Area Demarcation / Signage and Patrol 13 5. Pollution Sources 14 i. Waste Water Treatment Facilities (WWTF) 14 ii. Rain Events, Combined Sewer Overflows and Stormwater 15 C. Sanitary Survey 21 D. Predictable Pollution Events that cause Closure 21 1. Meteorological Events 21 2. Other Pollution Events that Cause Closures 23 E. Water Quality Monitoring Plan 23 1. Frequency of Monitoring 23 2. Monitoring Stations 24 3. Analysis of Water Samples 24 4. Toxic or Chemical Spills 24 5. Harmful Algae Blooms 24 6. Annual Evaluation of Compliance with NSSP Criteria 25 F. Closure Implementation Plan for the Providence River Conditional Area (GA 16) 27 1. Implementation of Closure 27 G. Re-opening Criteria 28 1. Flushing Time 29 2. Shellstock Depuration Time 29 3. Treatment Plant Performance Standards 30 H. Annual Reevaluation 32 I. Literature Cited 32 i Appendix A: Conditional Area Closure Checklist 34 Appendix B: Quahog tissue metals and PCB results 36 List of Figures Figure 1: Providence River, RI location map. ................................................................................ 6 Figure 2: Providence River watershed with municipal sewer service areas .................................. -

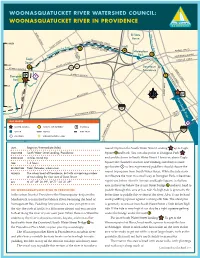

Woonasquatucket River in Providence95

WOONASQUATUCKET RIVER WATERSHED COUNCIL: Miles 1 SMITH STREET ORMS STREET WOONASQUATUCKET RIVER IN PROVIDENCE95 RIVER AVENUE RI State M o s House h PROMENADE STREET a s s 0 MILES u c k Mall KINSLEY AVENUE R VALLEY STREET River ket i uc 5 v at e ANGELL STREET ACORN 4 u r 1 sq STREET Waterplace na oo Park 3 W WATERMAN AVENUE Eagle ORIAL B .5 M O COLLEGE STREET ME U LE Square V A 0.25 R HARRIS AVENUE 6 Downtown D ATWELLS AVENUE 6 10 Providence BENEFIT STREET SOUTHMAIN WATER STREET ST ATWELLS AVENUE Donigian 7 2 Park 8 1A 25 DYER STREET 0. DEAN STREET 0.5 1 1 BROADWAY Providence River BIKE PATH 00 0.75 95 POST ROAD POINT WESTMINSTER STREET STREET Ninigret mAP LEGEND 9 Park 6 WATER ACCESS l POINTS OF INTEREST n P PARKING 195 n WATER ROADS BIKE PATH CAUTION CONSERVATION LAND u 10 n ELMWOOD AVE LEVEL Beginner/Intermediate (tides) round trip from the South Water Street Landing 1 up to Eagle START/END South Water Street Landing, Providence Square l6 and back. You can also put in at Donigian Park 8 RIVER MILES 4 miles round trip and paddle down to South Water Street. However, above Eagle TIME 1-2 hours Square the channel is narrow and winding and there is some 7 DESCRIPTION Tidal, flatwater, urban river quickwater u so less experienced paddlers should choose the round-trip option from South Water Street. While the tide starts SCENERY The urban heart of Providence, but with a surprising number of trees along the river west of Dean Street to influence the river in a small way at Donigian Park, it becomes 295 GPS N 41º 49’ 20.39”, W 71º 24’ 21.49” significant below Atwells Avenue and Eagle Square. -

Community Service Opportunities

Community Service - Learning Organizations and Opportunities Tiverton Schools 2012-2013 Hospitals and Medical Generally volunteering in a hospital or nursing home are approved activities. Assisting in private doctor or dental offices will not count for community service. PLEASE REMEMBER TO REPRESENT YOUR SCHOOL WELL AND FOLLOW ALL RULES AND EXPECTATIONS OF THE AGENCY OR ORGANIZATION STUDENTS ARE RESPONSIBLE TO TURN IN THEIR OWN DOCUMENTATION (It is also recommended that students keep copies of what they have done for their own records ) Charlton Memorial Hospital 363 Highland Avenue, Fall River, MA (508) 679-7038 Contact: volunteer coordinator at the hospital Jennifer Donovan Website: www.southcoast.org/services/charlton.htm Some positions require students be 14 or older Newport Hospital 11 Friendship Street Newport, RI (401) 845-1635 Contact: Lisa Coble E-mail: [email protected] Apply in March or April for summer positions St. Anne’s Hospital 795 Middle Street Fall River, MA 02721-1798 Contact: Volunteer Services Diane Palmer (508) 674-5600 x2080 Hospital Volunteer The Hospital Volunteer will provide support to the hospital staff and assistance to the patients, as appropriate. Duties will include such activities as passing out food and water to patients, distributing magazines and delivering flowers, providing clerical support, and working on the nursing floor or in a clinic environment. Must be 14 years of age, proof of immunization and TB Vaccination, and attend an orientation. Contact in May to inquire about summer positions The Rhode Island Veterans Home 480 Metacom Avenue Bristol, Rhode Island 02809 (401)253-8000 Ext. 695 The mission of the home is to provide quality nursing and residential care to those Rhode Island war veterans in need. -

Did You Fall in Love with Blackstone Heritage

Blackstone Heritage Corridor 2018 for a walk, a tour, a GO! bike ride, a paddle, a boat ride, a special event or harvest experience – all in the month of September Proudly in the wonderful Blackstone sponsored by River Valley National Heritage Corridor. GO! Table of Contents Welcome ........................ 2-3 Map ............................... 4 Listing of Experiences & Events ...................... 8-36 Trash Responsibly ........... 15 Be a GearHead! ................ 19 Page 19 Our Newest National Park ..37 Bikeway Maps ............ 38-40 VIP Program .................... 42 Photo Contest ................. 42 Support the Blackstone Heritage Corridor ............ 45 Online Shop .................... 45 Page 37 SEPTEMBER 2018 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Visit us at Page 38-40 BlackstoneHeritageCorridor.org for more free, guided experiences and special events (some may charge fees)! Updated daily. Page 42 670 Linwood Avenue Whitinsville, MA 01588 508-234-4242 BlackstoneHeritageCorridor.org Cover photo by Angie Stormont Page 42 ©2018 Blackstone Heritage Corridor, Inc. Table of Contents 1 The Blackstone River Valley National Heritage We welcome you Corridor is most notably known as the Birthplace to September in the of the American Industrial Revolution and the first place of tolerance and diversity in the Blackstone country. In the fall, its many other attributes come vividly into focus as the crispness of Heritage Corridor! autumn grows from the last warmth of summer. Explore our exceptional National Heritage Corridor during a season of anticipation. Every living thing is in preparation mode. Squirrels and chipmunks are gathering food for the winter. -

NBC Hydrographic Fall Surveys: Providence & Seekonk Rivers

NBC Hydrographic Fall Surveys: Providence & Seekonk Rivers Results of Hydrographic Surveys on the Providence and Seekonk Rivers: Fall Period, 2001 Draft Report Prepared for Microinorganics December, 2001 1.0 Introduction A second set of hydrographic surveys have been conducted within the Providence and Seekonk Rivers to characterize both the magnitudes and patterns of circulation within each body of water for fall seasonal conditions. The cruises provide a baseline for comparison with the first set performed the summer period (2001). The goal of this project is to map out basic aspects of flow and chemical transport within each river with particular emphasis on characterizing the levels of lateral and vertical structure in the flow during flood versus ebb periods of the tidal cycle. Specific questions involve mapping patterns for the outflows (e.g. plumes) for both near and far field regions of the rivers containing the Fields Point and Bucklin Point sewage discharge pipes 2.0 Instrument: Circulation patterns and energies are constrained within each river using an RD Instruments Broadband (1200 kHz) Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler. The ADCP consists of an array of four transducers oriented such that sound beams are transmitted out 90° angles from each other and a know angle from the central axis of the instrument. Sound pulses emitted by the transducers are reflected by scatterers throughout the water column, such as biological and other particulate matter. The reflected sound pulses are Doppler shifted due to the movement of the scatterers in the moving water. The ADCP processes the Doppler shifted return echoes to obtain along-beam velocity components which are then combined for each transducer and converted into a three-dimensional (3-D) velocity pattern. -

Points of Historical Interest in the State of Rhode Island

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Rhode Island History Special Collections 1911 Points of Historical Interest in the State of Rhode Island Rhode Island Department of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/ri_history Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Department of Education, Rhode Island, "Points of Historical Interest in the State of Rhode Island" (1911). Rhode Island History. 18. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/ri_history/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rhode Island History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rhode Island Education Circulars HISTORICAL SERIES-V POINTS OF HISTORICAL INTEREST IN THE STATE OF RHODE ISLAND PREPARED WITH THE CO-OPERATION OF THE Rhode Island Historical Society DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AFlCHIVEs Rhode Island Education Circulars rl HisTORICAL SERIEs-V /L'] I ' I\ l POINTS OF HISTORICAL INTEREST I N THE STATE OF RHODE ISLAND PREPARED WITH THE CO- OPERATION OF THE Rhode Island Historical Society DEPARTMENT OF E DUCATION STATE OF RHODE ISLAND PREFATORY NOTES. The pnmary object of the historical senes of the Rhode Island Education Circulars, the initial number of which was issued in 1908, is to supply the teachers and pupils of this state with important facts of Rhode Island history not generally found in text books and school libraries. For efficient civic training, it is essential that the children of our schools be taught the history and life of their own state. -

Estimated Water Use and Availability in the East Narragansett Bay Study Area, Rhode Island, 1995–99

Estimated Water Use and Availability in the East Narragansett Bay Study Area, Rhode Island, 1995–99 By Emily C. Wild Prepared in cooperation with the Rhode Island Water Resources Board Scientific Investigations Report 2007–5168 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Wild, E.C., 2007, Estimated water use and availability in the East Narragansett Bay study area: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2007–5168, 51 p. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................2 -

2017 DEA Pocket Manual

Division of Elderly Affairs Louis Pasteur Building-2nd Floor 57 Howard Avenue Cranston, RI 02920L The Division of Elderly Affairs (DEA) is responsible for the development of community- based services and programs that encourage independence and preserve the dignity of seniors and adults with disabilities. DEA is also designated as the state’s single planning and service area agency on aging under the provisions of the Older Americans Act. Main Telephone Number.....................462-3000 Hearing Impaired (TTY)......................462-0740 Administration…...……………………..462-0501 Elder Protective Services……….…….462-0555 Health Insurance Counseling..............462-0510 Home & Community Care...................462-0570 Media & Communications...................462-0509 Web Site......................................www.dea.ri.gov Follow us on Twitter: www.twitter.com/The_RIDEA Facebook: www.facebook.com/RIElderlyAffairs 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE POINT Network Program…………………………..................Page 4 Information and Referral Agencies………............6 Addiction Resources….…………………………....7 Adult Day Health Services………..……………….9 Advocacy……….……………………………….…13 Alzheimer’s Disease……..…………………….…16 Caregiver Support Programs………………….…17 Case Management………………………………..18 Chronic Disease Management……...…………...20 Community Action Programs………………….…25 Consumer Protection Programs………………...28 Dental Services………………………………...…30 Disability Resources………………….…………..33 Educational Programs……………………………39 Elder Abuse/Self-Neglect………………………..40 Emergency Preparedness………..……………..42 -

Mr. Mark C. Jewell 148 Bemon Street #2 Woonsocket, RI 02895 Dear Mr. Jewell

U.S.Department of Transportation 400 Seventh St., S.W. Washington, D.C. 20590 Federal Highway Administration May 25, 2004 Refer to: HOTO-I Mr. Mark C. Jewell 148 Bemon Street#2 Woonsocket,RI 02895 DearMr. Jewell: Thank you for your May 7 letter to the Federal Highway Administration's Associate Administrator for Operations, Jeffrey F. Paniati, concerning the safety and operations of shared-usepaths in Rhode Island (RI). Mr. Paniati has asked me to reply to your letter. We understand and share your concerns related to the RI State policy that requires pedestrians to "walk on left, facing bicycles." This requirement is potentially very confusing to pedestrians becauseit is different from the behavior that is expected of them on shared-usepaths in other States. The Manual on Unifonn Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) is the national standard for the design and application of all traffic control devices, including regulatory signs and pavement markings. However, the MUTCD does not govern the States and local jurisdictions in their authority to enact laws, regulations, and policies to regulate the use of roads and paths under their jurisdiction by pedestrians and other users. While we cannot require changes in RI State laws or regulations, we welcome the decision of the RI Department of Transportation to review their policy and consider changing it. We believe that the safety and convenience of all path users in RI would be best served by having the paths regulated in the same manner as other States, particularly the adjoining States. The pavement markings on 1he path shown on the photos you sent appear to be particularly confusing and they do not confonn to the MUTCD standards.