Native Advertising on TV: Effects of Ad Format and Media Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsday, February 21, 2009 Getting Into the Oscar and Indie Spirit

Ironbound Films, Inc. http://www.ironboundfilms.com/news/newsday022109.html Newsday, February 21, 2009 Getting into the Oscar and indie spirit Diane Werts AWARDS ALERT. With the Oscars on the Horizon, it's time for the too-cool "Independent Spirit Awards" (live today at 5 p.m., repeats tonight at midnight and tomorrow at 12:15 and 4 p.m., IFC; also tonight at 10 p.m., AMC). Indie fave Steve Coogan of "Tropic Thunder" and "Hamlet 2" hosts from Santa Monica, Calif. Contenders include "The Wrestler," "Ballast," "Rachel Getting Married," "Frozen River" and "Milk." Get a jump with the "Spirit Awards Nomination Special" (today at 4:30 p.m., IFC). Awards info at spiritawards.com. OSCARS EVERYWHERE. Yes, even the vintage swingfest "The Lawrence Welk Show" (tonight at 6, WLIW/21) offers a musical tribute to the Academy Awards. The 2009 soiree inspires lots of current-day chatter, too, including "Movie Mob" (today at 11 a.m. and 2 p.m., Reelz), "Academy Awards Preview" (today at 4 and 9 p.m., TV Guide Network), "Reel Talk" (tonight at 7, WNBC/4), and "The Road to Gold" (tonight at 7 and tomorrow at 5 a.m., WABC/7). Oscar afternoon revs up with "Countdown to the Red Carpet" (tomorrow 2-6 p.m., E!) and "Countdown to the Academy Awards" (tomorrow 3-6 p.m., TV Guide). Welcoming the stars to tomorrow's 8:30 p.m. live telecast are Ryan Seacrest's "Live From the Red Carpet" (tomorrow 6-8 p.m., E!) and Lisa Rinna and Joey Fatone's "Live at the Academy Awards" (tomorrow 6-8 p.m., TV Guide). -

Survival of the Fittest

Survival of the Fittest Sabine C. Bauer An original publication of Fandemonium Ltd, produced under license from MGM Consumer Products. Fandemonium Books PO Box 795A Surbiton Surrey KT5 8YB United Kingdom Visit our website: www.stargatenovels.com © 2011 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. All Rights Reserved. Photography and cover art: Copyright ©1997-2011 MGM Television Entertainment Inc./ MGM Global Holdings Inc. All Rights Reserved. METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER Presents RICHARD DEAN ANDERSON In STARGATE SG-1™ AMANDA TAPPING CHRISTOPHER JUDGE and MICHAEL SHANKS as Daniel Jackson Executive Producers ROBERT C. COOPER BRAD WRIGHT MICHAEL GREENBURG RICHARD DEAN ANDERSON Developed for Television by BRAD WRIGHT & JONATHAN GLASSNER STARGATE SG-1 © 1997-2011 MGM Television Entertainment Inc./MGM Global Holdings Inc. STARGATE: SG-1 is a trademark of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All rights reserved. WWW.MGM.COM No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written consent of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. To Tanya—beta extraordinaire and the one who‟s responsible for Everything! CONTENTS Prolog Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Prolog The childlike face— she‟d been a child, first and foremost, a smart, needy, tantrum-throwing teenager who‟d made an awful mistake— never moved. -

New Villains

2 NYP TV WEEK -I a 5 'Stargate' spin-off introduces new villains, o the Wraiths By MICHAEL GllTZ That's why the team in this sbow is trapped N the new Sci Fi series "Slargate: in a different galaxy and living in the lost city Atlantis" - a spin-off from the qui of Atlantis. It's fm from a safe \1~ven thanks to Oetly successful "Stargate SGI," which its alien technology, the lack of fdrce fields that just launched its eighth season - the lost leave it vulnerable to the elements and the city is finally rediscovered. But accord threat of new uber-villains, the:Wrruths. Ing 10 c<>-cr~3IOr Roh 'n ooper, it In conceiving the new show, ,Cooper doesn't should have OCCUlTed lljles ago. hesitate to name the one element of "SGI" he "We plannell for this t happen a was happiest to jettison. couple f years ngu." says oop 'r, "The Coa'uld," he says firmly about "SCI's" who "Iso helps oversee "SGt." main baddies, "I find them sort of ridiculous. "But we were victims of our That's something I probably shQuldn't be say own success because the ratings ing, considering I still executive produce the for 'SGI' kept growing on Sci Fi. other show. We originally planned the spin "They're great for 'SGI' and they have a spe off to be more of a hand-off. 'SGI' cific tone and feeling to them - these arro would be finishing and then we gant, theatrical, over-the-top, weird-dressing would pass the baton to ''Atlantis.'' bad guys," Cooper says. -

The Stargate Films

Mr. Wydey’s TV Series Episode Guides Stargate SG-1 Seasons 1-10 The Stargate films This collection of notes offers a strictly personal take on the whole of the Stargate SG-1 universe, as seen on television. The reports were gathered over many years as the episodes unfolded on Sky TV as seen by a Virgin Media customer. Until the Great Disaster of 2007. As will be revealed in due course, Sky and Virgin had a falling out and they did not make up for several years. The last couple of episodes of series 10 were not made available to your reviewer until 2011!! Of course, other TV channels have picked up the torch, and although Sky continues to show SG-1 in dribs and drabs, the Pick channel allowed fans to see the whole thing right from the start on weekdays from Monday to Friday, and at the time of this edition’s publication, Pick was showing everything for a second time. As well as living on in digital TV heaven, the world of the Stargate is also available on DVD. And there are two complete fan-fiction novels in the RLC collection currently, and another is in preparation. Clyde E. Wydey, May 2018 F&F BOOKS www.FarragoBooks.co.uk All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an archive or retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, physical or otherwise, without written permission from the author. The author asserts his moral right of identification. This Edition published in 2018 as part of a collection created by Farrago & Farrago and featuring the work of members of Romiley Literary Circle Cover by HTSP Graphics Division Design & typesetting by HTSP Editorial Division, 10 SK6 4EG, Romiley, G.B. -

Sg1-16-Four-Dragons-325.Pdf

FOUR DRAGONS By Diana Dru Botsford An original publication of Fandemonium Ltd, produced under license from MGM Consumer Products. Fandemonium Books PO Box 795A Surbiton Surrey KT5 8YB United Kingdom Visit our website: www.stargatenovels.com MGM TELEVISION ENTERTAINMENT INC. Presents RICHARD DEAN ANDERSON in STARGATE SG-1™ MICHAEL SHANKS AMANDA TAPPING CHRISTOPHER JUDGE DON S. DAVIS Executive Producers JONATHAN GLASSNER and BRAD WRIGHT MICHAEL GREENBURG RICHARD DEAN ANDERSON Developed for Television by BRAD WRIGHT & JONATHAN GLASSNER STARGATE SG-1 is a trademark of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. © 1997-2011 MGM Television Entertainment Inc. and MGM Global Holdings Inc. All Rights Reserved. METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER is a trademark of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Lion Corp. © 2011 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved. Photography and cover art: Copyright © 2011 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved. WWW.MGM.COM A Crossroad Press Digital Edition – web address. http://store.crossroadpress.com This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This eBook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to the vendor of your choice and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author. CONTENTS Four Dragons About the Author Sneak Preview of Stargate SG1: Oceans of Dust For my husband Rick, who keeps my feet firmly planted on the ground while my head and heart travel beyond the stars. -

Stargate | Oddity Central - Collecting Oddities

Stargate | Oddity Central - Collecting Oddities http://www.odditycentral.com/tag/stargate Home About Advertise Contact Contribute Disclaimer Privacy policy Search for: Pics News Videos Travel Tech Animals Funny Foods Auto Art Events WTF Architecture Home Father And Son Build Awesome Backyard Stargate By Spooky onJune 16th, 2010 Category: Pics , Tech Comments Off Back in 2005, when Stargate was the coolest sci-fi series around, sg1archive user ‘mango’ teamed up with his father to build a sweet replica of the stargate . 2 The project began in AUTOCAD, where the first blueprints were drawn. Since they didn’t have access to a plotter, plans had to be printed on A4 paper and stuck together, in a circle. The small details of the gate had to Tweet be drawn up from scratch, using photos and video footage. The skeleton of the gate is made up of 18 X-shaped pieces, and the spinning part is made from small planks. 89 The intricate stargate symbols had to be painstakingly carved, from wood, and chevrons first had to be carved from Styrofoam. The back of the stargate, though painted in gray, is totally fake, but the front looks realistic enough, with chevrons locking and everything. Thanks to an inner track, it even spins. Mango wasn’t too satisfied with the paint-job, but all in all this is a geeky masterpiece, just like the Stargate Share home-cinema . Be sure to check the video Mango made, at the bottom of the post. .. Subscribe via Rss Via Email Follow our Tweets on Twitter! 1 of 3 7/11/2012 9:54 PM Stargate | Oddity Central - Collecting Oddities http://www.odditycentral.com/tag/stargate Oddity Central on Facebook Like 8,667 people like Oddity Central . -

Sep/Oct 2019

THE WRIGHT STUFF Vol XXX No 5 The Official Newsletter of the U.S.S. Kitty Hawk NCC-1659 Sep/Oct 2019 THE WRIGHT STUFF PAGE 1 SEP / OCT 2019 C O N T E N T S THE CENTER SEAT ....................................................................................................... 3 John Troan COMPUTER OPERATIONS REPORT ........................................................................... 3 John Troan GENERATIONS OF STAR TREK FANS CELEBRATE AT GALAXYCON RALEIGH ......................................................................................................................... 4 T. Keung Hui RICHARD DEAN ANDERSON TELLS GALAXYCON RALEIGH FANS ABOUT MACGIVER AND STARGATE SG-1 ............................................................. 8 T. Keung Hui QUARTERMASTER/YEOMAN REPORT ..................................................................... 9 Larry Cox DAVID TENNANT AND CATHERINE TATE TALK ABOUT DOCTOR WHO AT GALAXYCON RALEIGH ........................................................... 10 T. Keung Hui A SPECIAL EVENING .................................................................................................. 11 Volume 30 - Number 5 Brad McDonald ENGINEERING REPORT ............................................................................................. 12 is a publication of the U.S.S. Kitty Hawk, the Brad McDonald Raleigh, N.C., chapter of STARFLEET, an international STAR TREK fan organization. This COMMUNICATIONS REPORT ................................................................................... 14 publication -

Stargate Magazine

SG_Download_Cover 15/10/0913:34Page1 STARGATE SG-1 © 1997-2009 MGM TELEVISION ENTERTAINMENT INC AND MGM GLOBAL HOLDINGS INC. STARGATE SG-1 IS A TRADEMARK OF METRO-GOLDWYN- MAYER STUDIOS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. TITAN AUTHORIZED USER. STARGATE: ATLANTIS © 2004-2009 MGM GLOBAL HOLDINGS INC. STARGATE: ATLANTIS IS A TRADEMARK OF METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER STUDIOS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. TITAN AUTHORIZED USER. STARGATE UNIVERSE © 2009 MGM GLOBAL HOLDINGS INC. STARGATE UNIVERSE IS A TRADEMARK OF METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER STUDIOS INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. TITAN AUTHORIZED USER. SGDownload_2-3_Contents 27/10/09 14:38 Page 2 CONTENTS 04 04 UNIVERSE 101 Everything you really need to Editorial Editor Brian J. Robb A WHOLE NEW UNIVERSE know about the brand new Contributing Editor Emma Matthews Stargate Universe show! Design Louise Brigenshaw, Dan Bura, Welcome to this special download edition of Stargate Magazine! Across the Oz Browne, Simon Christophers Subbing Zoe Hedges, Neil Edwards, following 40 pages you’ll find a sampling of features from recent editions of Simon Hugo, Kate Lloyd 08 ROBERT CARLYLE Contributors Paul Spragg, Stephen Eramo, Stargate Magazine, giving a flavor of the kind of content regularly featured. Bryan Cairns, Emma Matthews INTERVIEW We’ve got star interviews (Robert Carlyle, Michael Shanks, Ben Browder), details No-one was more surprised Special Thanks to: than Robert Carlyle when Karol Mora at MGM of the brand new Stargate Universe series and quirky character-based features. Carol Marks George he was approached to play Jon Rosenberg Check out page 33 for a guide to the kind of content featured in our regular Dr Rush on Stargate Universe. -

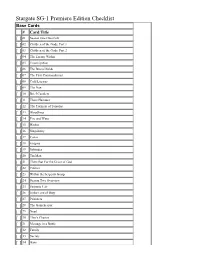

Stargate SG-1 Premiere Edition Checklist

Stargate SG-1 Premiere Edition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Season One Overview [ ] 02 Children of the Gods, Part 1 [ ] 03 Children of the Gods, Part 2 [ ] 04 The Enemy Within [ ] 05 Emancipation [ ] 06 The Broca Divide [ ] 07 The First Commandment [ ] 08 Cold Lazarus [ ] 09 The Nox [ ] 10 Brief Candlew [ ] 11 Thors Hammer [ ] 12 The Torment of Tantalus [ ] 13 Bloodlines [ ] 14 Fire and Water [ ] 15 Hathor [ ] 16 Singularity [ ] 17 Cor-ai [ ] 18 Enigma [ ] 19 Solitudes [ ] 20 Tin Man [ ] 21 There But For the Grace of God [ ] 22 Politics [ ] 23 Within the Serpents Grasp [ ] 24 Season Two Overview [ ] 25 Serpents Lair [ ] 26 In the Line of Duty [ ] 27 Prisoners [ ] 28 The Gamekeeper [ ] 29 Need [ ] 30 Thor's Chariot [ ] 31 Message in a Bottle [ ] 32 Family [ ] 33 Secrets [ ] 34 Bane [ ] 35 The Tok'ra (Part I) [ ] 36 The Tok'ra (Part II) [ ] 37 Spirits [ ] 38 Touchstone [ ] 39 The Fifth Race [ ] 40 A Matter of Time [ ] 41 Holiday [ ] 42 Serpents Song [ ] 43 One False Step [ ] 44 Show and Tell [ ] 45 1969 [ ] 46 Out of Mind [ ] 47 Season 3 Overview [ ] 48 Into The Fire [ ] 49 Seth [ ] 50 Fair Game [ ] 51 Legacy [ ] 52 Learning Curve [ ] 53 Point of View [ ] 54 Dead Man's Switch [ ] 55 Demons [ ] 56 Rules of Engagement [ ] 57 Forever in a Day [ ] 58 Past & Present [ ] 59 Jolinar's Memories [ ] 60 The Devil You Know [ ] 61 Foothold [ ] 62 Pretense [ ] 63 Urgo [ ] 64 A Hundred Days [ ] 65 Shades of Gray [ ] 66 New Ground [ ] 67 Maternal Instinct [ ] 68 Crystal Skull [ ] 69 Nemesis [ ] 70 Checklist 1 [ ] 71 Checklist 2 [ ] 72 Checklist 3 Stargate Aliens (1:3 Packs) # Card Title [ ] X1 The Asgards [ ] X2 The Spirits [ ] X3 The Oannes [ ] X4 The Aliens of P3X-118 [ ] X5 The Tiermods [ ] X6 The Nox [ ] X7 The Unas [ ] X8 Aliens of PJ2-455 [ ] X9 The Argosians Stargate Stars (1:7 Packs) # Card Title [ ] S1 Colonel Jack O'Neill [ ] S2 Dr. -

Major Samantha Carter

Richard Dean Anderson A1 Autograph Card as Colonel Jack O'Neill C3 Costume Card Major Samantha Carter Teal'c I SketchaFEX Stargate SG-1 season 4 Teal'c II SketchaFEX Stargate SG-1 season 4 Michael Shanks and DA1 Autograph Card Amanda Tapping Relic Card of 60's Style R9 Relic Card Poster from "1969" G2 Kneel Before Your God Apophis A67 Autograph Card Claudia Black as Vala A70 Autograph Card Richard Dean Anderson A73 Autograph Card Isaac Hayes as Tolok Dan Castellaneta as Joe A76 Autograph Card Spencer Christopher Judge as DA2 Autograph Card Teal'c and Tony Amendola as Bra'tac Claudia Black as Vala and DA3 Autograph Card Michael Shanks as Dr. Daniel Jackson Ben Browder as Lt. Col. A85 Autograph Card Cameron Mitchell Michael Shanks and Ben DA4 Autograph Card Browder PC1 Stargate Patch Cards Colonel Jack O'Neill PC2 Stargate Patch Cards Dr. Daniel Jackson Lt. Colonel Samantha PC4 Stargate Patch Cards Carter Claudia Black as Vala A108 Autograph Card Mal Doran A96 Autograph Card Rene Auberjonois as Alar Amanda Tapping as Autograph Card Samantha Christopher Judge as Autograph Card Teal'c C56 Costume Card President Landry Beau Bridges as Major A86 Autograph Card General Hank Landry David Hewlett as Dr. Autograph Card Rodney McKay David Hewlett as Dr. Autograph Card Rodney McKay Amanda Tapping as Autograph Card Major Carter Jason Momoa as Ronon Autograph Card Dex Vala Mal Dual Costume Card Stargate Heroes Doran Samantha Dual Costume Card Stargate Heroes Carter Michael Shanks as Dr. Jackson - Autographed Costume Card Beau Bridges as Major General Hank Landry - Autographed Costume Card Amanda Tapping as Major Carter - Autographed Costume Card Richard Dean Anderson - Autographed Costume Card R75 Bug Prop Card Stargate SG-1 Season 5 SketchaFEX Checklist 3. -

Re-Producing Whiteness in Stargate SG-1

Traveling Through the Iris: Re-producing Whiteness in Stargate SG-1 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in American Studies in the University of Canterbury by Kim Louise Parrent University of Canterbury 2010 i Table of Contents List of Figures …………………………………………………………….................. ii Acknowledgements …………………………………………..................................... iii Abstract …………………………………………………........................................... iv Introduction Opening the Iris: U.S. Science Fiction and Representation ................... 1 Structure of the Thesis Scope and Limitations Chapter 1 Review of the Literature ……………........................................................ 11 Approaching the Study of Whiteness Viewing and Seeing Whiteness Science Fiction Television and Whiteness The Colonial Gaze within Science Fiction Television Conclusion Chapter 2 Presenting Whiteness in “Children of the Gods” & “The Enemy Within”……………………………………………............................. 32 The Invisibility and Normality of Whiteness Imperial Discourses in Stargate SG-1 Colonizing the Landscape Manifest Destiny Travels into Space Fictions of the White Self & the White Hero as Saviour Colonel Jack O‟Neill Dr. Daniel Jackson Conclusion Chapter 3 Whiteness as Superiority and Terror in “Enigma” ………....................... 58 Technology as a Measure of Superiority The Fallacy of Cultural Superiority ii The Natural World & the Negation of Culture Representations of Whiteness as Symbolic Terror Physical Violence and White -

Gobierno Busca Acentuar Control Alimentario Con Nueva

PREMIO NACIONAL DE PERIODISMO 1982 / 1989 / 1990 3 4° D o m i n go 24 de julio de 2016 Año LVII Puerto La Cruz. Edición 21 .743 EL Tigre. Edición 3.743 w w w.e l t i e m p o.co m .ve EL PERIÓDICO DEL PUEBLO ORIENTAL PMVP Bs 150,00 Fecha de Marcaje 07/16 En junio fueron robados Pruebas de fraude del RR 10 autobuses de la línea La canciller Delcy Rodríguez calificó de mentirosa a la MUD al declarar sobre +2 el avance de posibles acuerdos con el Gobierno. Agregó que si insisten en el Puerto La Cruz- Santa Fe referendo, presentarán pruebas de irregularidades en esa jornada +9 PREGUNTA DE LA SEMANA: ¿Qué tiene planificado para las vacaciones escolares? Vote en w w w.eltiempo.com.ve EJECUTIVO // MAYOR GENERAL SERGIO RIVERO: TODOS LOS CONTENEDORES QUE SALGAN DE GUANTA SERÁN ESCOLTADOS POLÍTIC A Plat aforma aspira a evitar Gobierno busca acentuar control frac tura del chavismo alimentario con nueva misión +10 MUNDO El Plan Bolívar 2000, ideado por el entonces presidente Hugo crea los Clap y la Gran Misión Abastecimiento Soberano, con la Chávez, fue la génesis de la estrategia oficial para llevar comida casa cual abarca una actividad que no tenía bajo su supervisión: la por casa. En 2003 vendría la Misión Alimentación para “garantizar la movilización de los rubros desde los puertos hasta los super- distribución equitativa en la población”. 13 años después el Ejecutivo mercados. Así el dominio sobre los productos es total +4,5 De sorpresa Atent ado suicida dejó 80 La madrugada de ayer, la Guardia Nacional ca- muer tos yó de improviso en el en Afganistán mercado municipal de +11 Puerto La Cruz.