Assignment: Common MGT 360 Management Analysis Report [email protected] [ Updated: Monday, May 21, 2018 ]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitsubishi Corporation INVESTORS'note

Mitsubishi Corporation INVESTORS’NOTE [Security code 8058] JUN. 2010 No. 30 To Our Shareholders Top Message Tackle Everything Head On Ken Kobayashi President and CEO Appointment as New President It is my pleasure to write this letter following my confirmation as MC’s new president as of June 24. I joined MC in 1971 and was consistently involved with our machinery businesses, particularly ship-related business, from the early days of my career through the middle stages up to my promotion to division COO. From 2001, I resided in Singapore, the key hub for information in Asia, as general manager of our Singapore Branch, and witnessed firsthand the dynamism of the Asian economy, particularly the rapid growth of the Chinese economy. Following my appointment in 2007 as an executive vice president, I focused on creating a new business model of shosha-type industrial finance as CEO of the Industrial Finance, Logistics & Development Group under the guidance of our former president Yorihiko Kojima. Sogo-shosha have long used financing as a tool in their business activities. 1 Top Message However, under this business model we began to target Strengthening the Management Base, financing as a future nucleus of MC’s overall operations by Developing Future Growth Drivers coordinating and cooperating with internal departments. One principle I have learned through various kinds of Today, the global economy is facing structural change. work and stuck to throughout my career is to tackle things Globalization, the growing prominence of emerging nations, head on, without resorting to dubious wheeling and dealing. changes in the balance of resource demand and supply, and Even if somehow taking a less than acceptable approach various other dynamics are catalyzing a change from the brings success, it is bound to be short-lived. -

Mitsubishi Materials Corp

NEWS RELEASE Apr 14, 2021 R&I Affirms A-, Stable: Mitsubishi Materials Corp. Rating and Investment Information, Inc. (R&I) has announced the following: ISSUER: Mitsubishi Materials Corp. Issuer Rating: A-, Affirmed Rating Outlook: Stable RATIONALE: Mitsubishi Materials Corp. (MMC) is a major non-ferrous materials company that develops a full range of businesses including the manufacture of materials such as metals and cement, as well as the processing of materials that offers copper & copper alloy, electronic materials & components, and cemented carbide products. The company as a whole has a relatively robust earnings base, partly because it offers many products through the integrated production system among group companies that encompasses upstream to downstream processes. MMC has well-diversified earnings sources. However, the earnings are susceptible to changes in the economic situation, market conditions, raw material prices and foreign exchange rates, because MMC's offerings are mainly capital goods. The company had to see a decline in earnings affected partly by decreased automobile production in the first half of 2020 in addition to the global economy having slowed down since 2019. From the second half of 2020 onward, its earning capacity is beginning to show an upward trend buoyed by a rise in metal prices and a clear trend toward product demand recovery but is still not satisfactory for the rating. While transferring the unprofitable sintered parts business, MMC is promoting its business structure improvement including acquisition of stakes in copper mines and restructuring of its cutting tools subsidiary, investment in a company engaged in the tungsten business, etc. in Vietnam. -

59 the ACID EXTRACTION PROCESS T.INOUE,Unitika LTD

Goumans/Senden/van der Sloot, Editors Waste Materials in Construction: Putting Theory into Practice 91997 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. 59 THE ACID EXTRACTION PROCESS T.INOUE,Unitika LTD. Kyutaro-cho,Chuo-ku,Osaka,541 ,Japan H.KAWABATA,Kobe Steel LTD. IwayaNakamachi 4-chome,Nada, Hyogo,657,Japan Abstract Considering from a point of view of the recycling of resources that melting fly ash produced by melting the fly ash and incineration residue discharged from incinerators of municipal refuse is useful resources of concentrated heavy metals, this paper presents acid extraction processes developed for using the useful heavy metals and salts produced from the fly ash and melting fly ash as the resources. This paper reports the acid extraction processes from the fly ash in terms of the operational results of AES Processes operated at present and the problems to be solved in the future. This paper also reports the application of the acid extraction processes to the melting fly ash in terms of the description of the separating recovery process of heavy metals operated at present in a bench scale, the experimental results and the problems to be solved in the future. 1. INTRODUCTION Approximately 50 million tons of the municipal refuse is discharged every year in Japan and 78% of it is incinerated. The bottom ash and the fly ash are produced as the incineration residue in the incinerators and the fly ash containing low-boiling heavy metals are treated and landfilled by any of four techniques (melting-solidification, cementing-solidification, chemical stabilization and acid extraction) designated for "Specially Controlled Municipal Wastes" by "the Waste Disposal and Public Cleansing Law". -

Next-Generation Power Modules Patent Landscape Analysis

From Technologies to IP Business Intelligence Next-Generation Power Modules Patent Landscape Analysis January 2021 © 2021 | www.knowmade.com TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 •Technology coverage of IP portfolios US IP players 228 •Introduction •Top patent assignees in each segment GE, Cree/Wolfspeed, Ford, On Semiconductor •Scope of the report •EV/HEV applications vs. Semicon. Device Taiwanese IP players 265 •Key feature of the report Technology Delta Electronics •Main patent assignees cited in the report •Reduction of parasitics vs. Semicon. Device Technology Korean IP players 274 METHODOLOGY 15 Hyundai/Kia, Samsung Electronics/SEMCO •Patent search, selection and analysis IP PROFILES OF KEY IP PLAYERS 61 For each player: Chinese IP players 282 •Patent segmentation Midea, CRRC, Starpower, Gree, SGCC, CETC, BYD, •Terminology for patent analysis • Statistical analysis of the portfolio (IP tends, geographical coverage, granted patents, pending Macmic, Shenzhen Yitong Power Electronics patent applications, technology, technical EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 21 CONCLUSION 318 challenges, applications) PATENT LANDSCAPE OVERVIEW 31 • Noteworthy patents relating new KNOWMADE PRESENTATION 322 •Time evolution of patent publications products/technology developments •Top patent assignees • Description of the recent patenting activity •Short description of main patent assignees Japanese IP players 62 •Current legal status of the top patent portfolios Mitsubishi Electric, Hitachi, Denso, Rohm, Fuji •Countries of filings for granted and pending Electric, Toyota -

Basic Agreement on the Integration of Road-Related Business Between Nippon Steel Metal Products Co., Ltd

March 4, 2020 Nippon Steel Corporation Kobe Steel, Ltd. Nippon Steel Metal Products Co., Ltd. Kobelco Engineered Construction Materials Co., Ltd. Basic agreement on the integration of road-related business between Nippon Steel Metal Products Co., Ltd. and Kobelco Engineered Construction Materials Co., Ltd. Nippon Steel Corporation (“Nippon Steel”), its 100% subsidiary Nippon Steel Metal Products Co., Ltd. (“Nippon Steel Metal Products”), Kobe Steel, Ltd. (“Kobe Steel”) and its subsidiary Kobelco Engineered Construction Materials Co., Ltd. (“Kobelco Engineered Construction Materials”) today reached a basic agreement on (i) the integration of the road-related business (such as guard fencing and soundproof walls) of Nippon Steel Metal Products and all businesses of Kobelco Engineered Construction Materials (the “Integration”) and (ii) the initiation of discussions on the specific conditions towards the Integration, which is expected to be concluded on April 1, 2021. The details are as follows: 1. Purpose of the Integration Nippon Steel Metal Products and Kobelco Engineered Construction Materials have been long engaged in road-related businesses respectively. Both companies have responded to a variety of customer needs and have made certain contributions to the establishment of infrastructure in society. The environment surrounding road-related business is severe due to the shrinkage of road construction investment caused by the ongoing reduction of public investment. This trend is expected to continue as a result of the shrinking population -

Health Newsletter 11 February 99

BDA Business Development Asia ASIA IS A BUSINESS IMPERATIVE… NOW MORE THAN EVER ASIAN AUTOMOTIVE NEWSLETTER Issue 31, June 2002 A bimonthly newsletter of developments in the auto and auto components markets CONTENTS CHINA INTRODUCTION .................................................... 1 Alpine Electronics, the Japanese car audio CHINA ................................................................... 1 specialist, will expand production in China by INDIA ..................................................................... 3 increasing output at two subsidiaries in Liaoning JAPAN................................................................... 4 Province. Alpine will invest a total of ¥3bn (US$24m) KOREA ................................................................. 5 in the two units by March 2004. China’s share of MALAYSIA ............................................................ 5 total Alpine production will rise from 25% to 40% PHILIPPINES ........................................................ 5 by 2004. Overall, Alpine’s ratio of offshore production THAILAND............................................................. 6 will increase from 70% to 90%. (May 29, 2002) Auto Parts Holdings Sdn Bhd, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Malaysian automotive component manufacturer APM Automotive Holdings Berhad, has formed a JV with Hefei WinKing Asset Co Ltd (HWAC) of China to manufacture and distribute automotive seats, interior parts and metal INTRODUCTION components in China. The new JV, Anhui Winking Auto Parts Manufacturing Co Ltd, will be 60% held by APM with the remaining 40% held by HWAC. The JV will be created with an authorized We hope you find the Asian Automotive Newsletter capital of US$5m and an initial paid-up capital of informative. US$3m. Based in Heifei, China, Anhui Winking will begin supplying seats by Q4 2002 to Jianghuai BDA is a corporate finance advisory firm which Automotive Group, an associate of HWAC. assists multinational clients to identify and execute Annual production capacity is 20,000 seat sets. -

Kobe Steel, Ltd. 1. Basic Policy

(Translation) Date of Latest Update: June 27, 2019 Kobe Steel, Ltd. Mitsugu Yamaguchi, President, CEO and Representative Director Contact: Kazuyuki Honda, General Manager of the Corporate Communications Department Code Number: 5406 http://www.kobelco.co.jp This statement is intended to inform you of the current status of the corporate governance of Kobe Steel, Ltd. (the “Company”). Basic Policy on Corporate Governance and Capital Structure, Corporate Data, and Other Basic Information 1. Basic policy <Fundamental Position on Corporate Governance> The Kobe Steel Group recognizes that corporate value includes not only business results and technological capabilities, but also the attitude toward social responsibility related to business activities for all stakeholders such as shareholders, investors, customers, business partners, employees in the Kobe Steel Group and local community members. Earnestly, undertaking efforts to improve for all stakeholders leads to an improvement in corporate value. Therefore, corporate governance is not merely a form of the organization, but is a framework to realize all the efforts the Kobe Steel Group is undertaking. In building the framework, the Group recognizes the importance of establishing a system that contributes to improving corporate value by taking appropriate risks; acting in cooperation with stakeholders; promoting appropriate dialogue with investors in the capital market; maintaining the rights of and fairness for shareholders; and securing transparency in business dealings. Under such a policy, the Kobe Steel Group has established the Core Values of KOBELCO, which are promises that the Group has made to society demonstrating the values shared throughout the Group, and the Six Pledges of KOBELCO Men and Women, which are concrete actions to fulfill the Core Values of KOBELCO that all employees must carry out. -

Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #188-09 September 2009 Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani Cite as: James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani. (2009). “Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?” IRLE Working Paper No. 188-09. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/188-09.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Working Paper Series (University of California, Berkeley) Year Paper iirwps-- Whither the Keiretsu, Japan’s Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln Masahiro Shimotani University of California, Berkeley Fukui Prefectural University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/iir/iirwps/iirwps-188-09 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. WHITHER THE KEIRETSU, JAPAN’S BUSINESS NETWORKS? How were they structured? What did they do? Why are they gone? James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 USA ([email protected]) Masahiro Shimotani Faculty of Economics Fukui Prefectural University Fukui City, Japan ([email protected]) 1 INTRODUCTION The title of this volume and the papers that fill it concern business “groups,” a term suggesting an identifiable collection of actors (here, firms) within a clear-cut boundary. The Japanese keiretsu have been described in similar terms, yet compared to business groups in other countries the postwar keiretsu warrant the “group” label least. -

Mitsubishi Materials and Ube Industries Sign Letter of Intent for Integration of Cement Businesses

February 12, 2020 Company name: Mitsubishi Materials Corporation Representative: Naoki Ono, Chief Executive Officer Security code: 5711 (shares listed on First Section of Tokyo Stock Exchange) Contact: Nobuyuki Suzuki General Manager, Corporate Communications Department, General Affairs Department Tel: +81-3-5252-5206 Company name: Ube Industries, Ltd. Representative: Masato Izumihara, President and Representative Director Security code: 4208 (shares listed on First Section of Tokyo Stock Exchange and Fukuoka Stock Exchange) Contact: Osamu Akutagawa General Manager, CSR & General Affairs Department Tel: +81-3-5419-6110 Mitsubishi Materials and Ube Industries Sign Letter of Intent for Integration of Cement Businesses Mitsubishi Materials Corporation and Ube Industries, Ltd. announced today that, based on a resolution of the companies’ respective Board of Directors meetings held today, they have signed a letter of intent to start specific discussions and study on the integration of their respective cement businesses and related businesses. The details of the integration, which is to be implemented around April 2022, are given below. Moving forward, Mitsubishi Materials and Ube Industries will engage in specific discussions and study on the integration, and they plan to sign a definitive agreement for the integration in or around late September 2020. 1. Purpose of the Integration In 1998, Mitsubishi Materials and Ube Industries established Ube-Mitsubishi Cement Corporation as an equally-owned joint venture. Under the joint venture, the companies -

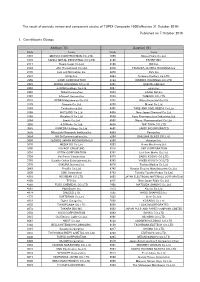

Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change the Result Of

The result of periodic review and component stocks of TOPIX Composite 1500(effective 31 October 2016) Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change Addition( 70 ) Deletion( 60 ) Code Issue Code Issue 1810 MATSUI CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 1868 Mitsui Home Co.,Ltd. 1972 SANKO METAL INDUSTRIAL CO.,LTD. 2196 ESCRIT INC. 2117 Nissin Sugar Co.,Ltd. 2198 IKK Inc. 2124 JAC Recruitment Co.,Ltd. 2418 TSUKADA GLOBAL HOLDINGS Inc. 2170 Link and Motivation Inc. 3079 DVx Inc. 2337 Ichigo Inc. 3093 Treasure Factory Co.,LTD. 2359 CORE CORPORATION 3194 KIRINDO HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 2429 WORLD HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3205 DAIDOH LIMITED 2462 J-COM Holdings Co.,Ltd. 3667 enish,inc. 2485 TEAR Corporation 3834 ASAHI Net,Inc. 2492 Infomart Corporation 3946 TOMOKU CO.,LTD. 2915 KENKO Mayonnaise Co.,Ltd. 4221 Okura Industrial Co.,Ltd. 3179 Syuppin Co.,Ltd. 4238 Miraial Co.,Ltd. 3193 Torikizoku co.,ltd. 4331 TAKE AND GIVE. NEEDS Co.,Ltd. 3196 HOTLAND Co.,Ltd. 4406 New Japan Chemical Co.,Ltd. 3199 Watahan & Co.,Ltd. 4538 Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries,Ltd. 3244 Samty Co.,Ltd. 4550 Nissui Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd. 3250 A.D.Works Co.,Ltd. 4636 T&K TOKA CO.,LTD. 3543 KOMEDA Holdings Co.,Ltd. 4651 SANIX INCORPORATED 3636 Mitsubishi Research Institute,Inc. 4809 Paraca Inc. 3654 HITO-Communications,Inc. 5204 ISHIZUKA GLASS CO.,LTD. 3666 TECNOS JAPAN INCORPORATED 5998 Advanex Inc. 3678 MEDIA DO Co.,Ltd. 6203 Howa Machinery,Ltd. 3688 VOYAGE GROUP,INC. 6319 SNT CORPORATION 3694 OPTiM CORPORATION 6362 Ishii Iron Works Co.,Ltd. 3724 VeriServe Corporation 6373 DAIDO KOGYO CO.,LTD. 3765 GungHo Online Entertainment,Inc. -

Japanese Ship Machinery and Traders List 2020 Japanese Ship Machinery and Traders List

Japanese Ship Machinery and Traders List 2020 Japanese Ship Machinery and Traders List PRODUCTS LIST Machinery part 9-1.Pump Alfa Laval K. K. 14-2.Auto Pilot Furuno Electric Co., Ltd. 26-4.Gas Detection Systems Consilium Nittan Marine Ltd. 1-1.Low Speed Diesel Engines Akasaka Diesels Ltd. Daito Pump Kogyo Co., Ltd. Tokyo Keiki Inc. Port Enterprise Co., Ltd. (Up to 200 min-1) IHI Power Systems Co., Ltd. Daikin MR Engineering Co., Ltd. Wärtsilä Japan Ltd. 26-5.Sewage Treatmet Equipment Goko Seisakusho Co., Ltd. Hitachi Zosen Corporation DMW CORPORATION YAMAX Co., Ltd. Ishii Machinery Works, Co., Ltd. IMEX Co., Ltd. HEISHIN Ltd. Yokogawa Denshikiki Co., Ltd. Sasakura Engineering Co., Ltd. Japan Engine Corporation HSN-KIKAI KOGYO CO., LTD. 14-3.Voyage Data Recorder Consilium Nittan Marine Ltd. Taiko Kikai Industries Co., Ltd. Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd. IWAKITEC Co., Ltd. (VDR) Furuno Electric Co., Ltd. Wärtsilä Japan Ltd. Makita Corporation Ishii Machinery Works, Co., Ltd. Japan Radio Co., Ltd. 26-6.Remote Operated Units for Misuzu Machinery Co., Ltd. Mitsui E&S Machinery Co., Ltd. Ishikura Pump Mfg. Co., Ltd. Wärtsilä Japan Ltd. Valve Musasino Co., Ltd. The Hanshin Diesel Works, Ltd. MIURA CO., LTD. 14-4.GPS Navigater Furuno Electric Co., Ltd. Nakakita Seisakusho Co., Ltd. 1-2.Medium Speed Diesel Akasaka Diesels Ltd. Naniwa Pump Mfg. Co., Ltd. Japan Radio Co., Ltd. Sankyo Seisakusho Co., Ltd. Engines,Dual Fuel Engines Daihatsu Diesel Mfg. Co., Ltd. Sanshin Electric Corporation Wärtsilä Japan Ltd. SEMCO LTD. (200 - 1000 min-1) IHI Power Systems Co., Ltd. Shinko Ind. -

A Study on the Collapse Control Design Method for High-Rise Steel Buildings

A Study on the Collapse Control Design Method for High-rise Steel Buildings by Akira Wada 1, Kenichi Ohi 2, Hiroyuki Suzuki 3, Mamoru Kohno 4 and Yoshifumi Sakumoto 5 ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION Two direct causes led to the collapse on The collapse of the World Trade Center towers September 11, 2001 of the World Trade Center (WTC1 and WTC2) was the direct result of towers: column damage caused by aircraft crash column damage and large-scale fires caused by and the resulting large-scale fires. In spite of this airplane crashes. In spite of this, WTC1 and damage, the towers remained standing after the WTC2 remained standing for 102 minutes and crashes for 102 and 56 minutes, respectively, 56 minutes respectively, during which many during which many lives were saved. The lives were saved. The fact that so many lives collapse of the WTC towers, however, may be were saved is reportedly due to the large taken as an alert that local failures can trigger a deformation capacity or load redistribution progressive collapse. It was also a landmark capacity inherent in steel structures [1]. From event in that it alerted construction engineers to this, it can be understood that the tower the importance of preventing progressive structures of the World Trade Center (hereinafter collapse in similar structures. referred to as “WTC”) had a certain degree of redundancy. Nevertheless, the WTC collapse Prevention of progressive collapse requires the serves as a warning about progressive collapse development of design technologies for frames triggered by a local collapse that causes an that have high redundancy.