A Written Creative Work Submitted to the Faculty of San Francisco State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for ^ the Degree 3G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Clique Song List 2000

The Clique Song List 2000 Now Ain’t It Fun (Paramore) All About That Bass (Meghan Trainor) American Boy (Estelle & Kanye West) Applause (Lady Gaga) Before He Cheats (Carrie Underwood) Billionaire (Travie McCoy & Bruno Mars) Birthday (Katy Perry) Blurred Lines (Robin Thicke) Can’t Get You Out Of My Head (Kylie Minogue) Can’t Hold Us (Macklemore & Ryan Lewis) Clarity (Zedd) Counting Stars (OneRepublic) Crazy (Gnarls Barkley) Dark Horse (Katy Perry) Dance Again (Jennifer Lopez) Déjà vu (Beyoncé) Diamonds (Rihanna) DJ Got Us Falling In Love (Usher & Pitbull) Don’t Stop The Party (The Black Eyed Peas) Don’t You Worry Child (Swedish House Mafia) Dynamite (Taio Cruz) Fancy (Iggy Azalea) Feel This Moment (Pitbull & Christina Aguilera) Feel So Close (Calvin Harris) Find Your Love (Drake) Fireball (Pitbull) Get Lucky (Daft Punk & Pharrell) Give Me Everything (Tonight) (Pitbull & NeYo) Glad You Came (The Wanted) Happy (Pahrrell) Hey Brother (Avicii) Hideaway (Kiesza) Hips Don’t Lie (Shakira) I Got A Feeling (The Black Eyed Peas) I Know You Want Me (Calle Ocho) (Pitbull) I Like It (Enrique Iglesias & Pitbull) I Love It (Icona Pop) I’m In Miami Trick (LMFAO) I Need Your Love (Calvin Harris & Ellie Goulding) Lady (Hear Me Tonight) (Modjo) Latch (Disclosure & Sam Smith) Let’s Get It Started (The Black Eyed Peas) Live For The Night (Krewella) Loca (Shakira) Locked Out Of Heaven (Bruno Mars) More (Usher) Moves Like Jagger (Maroon 5 & Christina Aguliera) Naughty Girl (Beyoncé) On The Floor (Jennifer -

Mill Valley Oral History Program a Collaboration Between the Mill Valley Historical Society and the Mill Valley Public Library

Mill Valley Oral History Program A collaboration between the Mill Valley Historical Society and the Mill Valley Public Library David Getz An Oral History Interview Conducted by Debra Schwartz in 2020 © 2020 by the Mill Valley Public Library TITLE: Oral History of David Getz INTERVIEWER: Debra Schwartz DESCRIPTION: Transcript, 60 pages INTERVIEW DATE: January 9, 2020 In this oral history, musician and artist David Getz discusses his life and musical career. Born in New York City in 1940, David grew up in a Jewish family in Brooklyn. David recounts how an interest in Native American cultures originally brought him to the drums and tells the story of how he acquired his first drum kit at the age of 15. David explains that as an adolescent he aspired to be an artist and consequently attended Cooper Union after graduating from high school. David recounts his decision to leave New York in 1960 and drive out to California, where he immediately enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute and soon after started playing music with fellow artists. David explains how he became the drummer for Big Brother and the Holding Company in 1966 and reminisces about the legendary Monterey Pop Festival they performed at the following year. He shares numerous stories about Janis Joplin and speaks movingly about his grief upon hearing the news of her death. David discusses the various bands he played in after the dissolution of Big Brother and the Holding Company, as well as the many places he performed over the years in Marin County. He concludes his oral history with a discussion of his family: his daughters Alarza and Liz, both of whom are singer- songwriters, and his wife Joan Payne, an actress and singer. -

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

County Favors Smaller Airport Board

* Large Selection ExtendedExtended HoursHours of Liquors, Wine, Monday - SaturdayOPENOPEN From 8am - 11:30pm & Beer at Low, Sunday - 12:30pm Until 11:30pm 1920 Highway 18, West Point, GA Exit #2 off of I-85 Low Prices 476617 GUEST COOK: Cakes, cornbread are tops for church functions LaGrange Daily News WEDNESDAY 50 cents December 21, 2011 lagrangenews.com The weather ‘Sales are down, but people are buying’ County tomorrow High 70 favors Low 49 Rain smaller airport Today’s artist: Sarah McPhillips Battle, fifth board grade, Hollis Hand Elementary School By Matt Chambers Staff writer The Troup County Commission praised the county Airport Authority for its work and support- ed the reduction of its size Tuesday. Helping The commission passed a resolution putting its hands support behind a move that would cut the author- Gift wrapping ity board from 12 to seven at mall members. Volunteers are “The airport is approx- needed to help imately a $1 million enter- Emmaus prise,” said commission Jennifer Shrader / Daily News Women’s Shel- Chairman Ricky Wolfe. ter wrap Christ- Dennis McKeen, standing, and Jordan Beistline prepare to cut a tree at December Place Christmas Tree “There are five of us with mas gifts from 9 Farm. Local growers say they have been affected by the drought, although not as bad as tree farms in a $40 million budget; they a.m. to 10 p.m. are $1 million with 12 every day this Texas and other parts of the country. members.” week near Belk The Troup County Air- at LaGrange Christmas tree farms feel drought port Authority voted Mall. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Man Killed in Shootout with Police Identified Behind the Wheel of the Kia and Dead at the Scene

noW thREE dAYs A WEEK ••• Post CommEnts At on CAPE-CoRAL-dAiLY-bREEzE.Com Baker CAPE CORAL advances Local team wins in Mariner tournament BREEZE — SPORTS EARLY-WEEK Edition WEATHER:Partly Cloudy • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Wednesday: Chance of Rain — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 292 Tuesday, December 22, 2009 50 cents Man killed in shootout with police identified behind the wheel of the Kia and dead at the scene. Three others reportedly involved in home invasion charged started to speed away, according Three people in the KIA with to the statement. Richardson — identified by By DREW WINCHESTER Acres, died at the scene following on the Kia in front of the Steak N’ Additional shots were fired police as Jarrett Delshun Mundle, [email protected] an exchange of gunfire with Shake, ordering the driver out of from the Kia toward the police 19, of 2729 Colonial Blvd., Apt. Cape Coral police have police officers, according to a the vehicle, officials reported. officers, who returned fire. The 206, Fort Myers; Mike Borrell, released the name of a man killed prepared statement. The driver, Kia then crashed into the back of 27, of 3463 C St., Apt. 815, Fort in a shooting Sunday in front of He was a passenger in a white Patrick Rhodes Nelson, 19, of a police cruiser. Myers; and Nelson — each have the Steak N’ Shake on Pine Island Kia that was suspected to be have 2160 Clubhouse Road, North Officials reported Richardson been charged with felony murder Road East. been used in a home invasion rob- Fort Myers, did so after a shot exited the Kia after the crash, in the death, along with home Tyson Lee Richardson, 21, of bery Saturday night. -

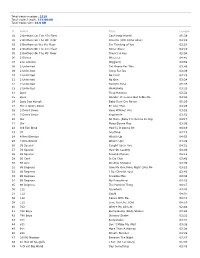

Total Tracks Number: 2218 Total Tracks Length: 151:00:00 Total Tracks Size: 16.0 GB

Total tracks number: 2218 Total tracks length: 151:00:00 Total tracks size: 16.0 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Can't Help Myself 05:39 02 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor Dreams (Will Come Alive) 04:19 03 2 Brothers on the 4th Floor I'm Thinking of You 03:24 04 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Never Alone 04:10 05 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor There's A Key 03:54 06 2 Eivissa Oh La La 04:41 07 2 In a Room Wiggle It 03:59 08 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This 03:40 09 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy 03:39 10 2 Unlimited No Limit 03:28 11 2 Unlimited No One 03:24 12 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 05:36 13 2 Unlimited Workaholic 03:33 14 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 15 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:34 16 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 17 Three Doors Down Be Like That 04:25 18 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:53 19 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:52 20 3lw No More (Baby I'm Gonna Do Rig 04:17 21 3lw Playa Gonna Play 03:06 22 3rd Eye Blind How Is It Gonna Be 04:10 23 3T Anything 04:15 24 4 Non Blondes What's Up 04:55 25 4 Non Blonds What's Up? 04:09 26 38 Special Caught Up In You 04:25 27 38 Special Hold On Loosely 04:40 28 38 Special Second Chance 04:12 29 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 30 50 cent Window Shopper 03:09 31 98 Degrees Give Me One More Night (Una No 03:23 32 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 03:43 33 98 Degrees Invisible Man 04:38 34 98 Degrees My Everything 04:28 35 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 04:27 36 112 Anywhere 04:03 37 112 Cupid 04:07 38 112 Dance With Me 03:41 39 112 Love You Like I Did 04:16 40 702 Where My Girls At 02:44 -

A Night of Frost

A Night of Frost by Siegfried “Zig” Engelmann A Night of Frost © S. Engelmann, 2007 Page 1 of 274 A NIGHT OF FROST PART ONE HENNA Summerʼs my season. Course that donʼt mean I sit around all summer like a piece of lawn furniture, because I damned well donʼt. Iʼm the cook at Camp Timberline and more than likely I work harder during the summer than you work all year long. But I like the summer. Itʼs nice to look out of my window in the campʼs kitchen and see the blue lakes and the yellow meadows, instead of nothing but snow. People who donʼt know any better are always talking about the New England winter, but you can take it from someone whoʼs lived up here all her life: The only good thing about a New England winter is that it only comes once a year. Around here, you can always tell when summer is on its way by the way Jay McFarland dresses. When he sheds that old bearskin coat of his and gets out of his drag-ass overalls, you know it wonʼt be long before the campers will be here. Oh, that McFarland! The gossiping cornballs around here tell a lot of wild stories about him if you give them half a chance, but thereʼs not a word of truth to most of them. One story even has it that McFarland used to be in the movies. Thatʼll give you a rough idea of the kind of purebred gossip that goes through these woods. Course McFarland is a bit different. -

Charlotte Balks at DJJ Bill

11’ Kayak, $425 In Today’s Classifieds! AND WEEKLY HERALD THECharlotte WIRE Sun PAGE 1 OPPONENTS TAKE AIM AT CRIST DRIVER STRUCK ON TRACK DIES Opponents say Charlie Crist can’t be trusted because of his Tony Stewart pulls out of the NASCAR Sprint Cup race in political conversion from Republican to independent to Democrat. Watkins Glen, N.Y., 12 hours after a fatal crash. SPORTS PAGE 1 An Edition of the Sun VOL. 122 NO. 223 AMERICA’S BEST COMMUNITY DAILY MONDAY AUGUST 11, 2014 www.sunnewspapers.net $1.00 HACKIN’ AROUND Pardon me Charlotte balks at DJJ bill By GARY ROBERTS detaining young offenders, Charlotte is among “post-disposition.” The two STAFF WRITER saying the county is being 23 counties mounting sides remain far apart on for asking … overcharged. Charlotte a Florida Association of how to define those and MURDOCK — Charlotte also is seeking to recoup Counties administrative other key terms. County officials are refus- $1.3 million in over-pay- challenge against the DJJ. For example, the counties rimary election day is just around ing to make a mandatory ments already made to the The dispute centers on argue that the DJJ misinter- the corner, school is set to begin, payment to the Florida DJJ. the DJJ’s handling of a 2004 preted the funding formula college football teams are practic- P Department of Juvenile “There’s a great potential law that requires counties by requiring them to pay ing and predicting conference or NCAA Justice for detention care. for us overpaying again,” said to help pay for “pre-disposi- for detaining juveniles who championships, and County commissioners assistant county attorney tion” — costs associated with violated probation and I’m thinking about unanimously voted on Dan Gallagher.