The 1980 Gardner Strike and Occupation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El XX Congreso Y Los Comienzos De La Desestalinización Nuestra Historia

Revista de Historia de la FIM Núm. 2, 2do semestre de 2016 El XX Congreso y los comienzos de la desestalinización Nuestra Historia Revista de Historia de la FIM Número 2 Segundo semestre de 2016 Usted es libre de: Ș Copiar, distribuir y comunicar públicamente esta obra. Bajo las siguientes condiciones: Ș No comercial: No puede utilizar los contenidos del Boletín para fines comerciales. Ș Sin obras derivadas: No puede alterar, transformar o generar una obra derivada a partir de esta obra. Con el siguiente caso particular: Ș Esta licencia no se aplica a los contenidos publicados procedentes de terceros (textos, gráficos, informaciones e imágenes que vayan firmados o sean atribuidos a otros autores). Para reproducir dichos contenidos será necesario el consentimiento de dichos terceros. Nuestra Historia: Revista de Historia de la FIM Edita: Fundación de Investigaciones Marxistas • Equipo coordinador: Manuel Bueno Lluch, Francisco Erice Sebares, José Gómez Alén y Julián Sanz Hoya • Diseño de portada: Francisco Gálvez ([email protected]) • Consejo de Redacción: Irene Abad Buil, Juan Andrade Blanco, Manuel Bueno Lluch, Claudia Cabrero Blanco, Francisco Erice Sebares, Juan Carlos García- Funes, José Gómez Alén, Fernando Hernández Sánchez, José Hinojosa Durán, David Ginard i Féron, Adrià Llacuna Hernando, Mirta Núñez Díaz-Balart, Victoria Ramos Bello, Julián Sanz Hoya, Víctor Santidrián Arias, Juan Trías Vejarano, Julián Vadillo Muñoz, Santiago Vega Som- bría • Envío de colaboraciones: [email protected] • Administración: c/ Olimpo 35, 28043, Madrid. Tfno: 913004969. Correo-e: [email protected] • web: www.fim.org.es • Foto de portada: TASR/AP (Fuente: http://rus-biography.ru) • ISSN: 2529-9808. -

Struggle to End the Social Contract Grows

A RUGG No.IO March 1977 ~10NTHL Y FIVE PENCE STRUGGLE TO END THE SOCIAL CONTRACT GROWS After 2 years of vicious wage cuts, many -Shop stewards representing 16,000 sections of workers throughout the workers at the British Aircraft Corpor country are militantly proclaiming their ation; opposition to a 'phase 3' of the social -Fords Convenors, representing 50,000 con-act. workers, demand pari ~ y with Fn~rl r f Europe and a 35 hour week; (co~t 'd on p2) They include: -Vauxhall Combine Committee Stewards; -Dockers at Hull and Southampton, at CONTENTS INCLUDE: large mass meetings; -The National Busmen, T&GWU; WORKERS OPPOSE TU PAYMENTS TO LABOUR -Nottinghamshire Miners' Delegates rep- IT IS PEOPLE, NOT WEAPONS, THAT ARE resenting 34,000 men; DECISIVE -British Leyland Shop Stewards, who plan a national campaign of opposition to BUILD THE REVOLUTIONARY . COM~~UNIST the social contract and a one day - PARTY - Central Task in Britain s~rike, while 10,000 Leyland workers NO INFLATION IN SOCIALIST CHINA marched against the social contract; JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE COMMUNIST FEDERATION OF BRITAIN (MARXIST-LENINIST) Struggle to end the social contract grows (cont'd from p.l) -ASLEF, train drivers,demanding £20 p.w. is excellent and must be strengthened. rise, to make up wage cuts over last Only direct action by the rank-and-file two years; can sweep aside the opportunist TU -Arthur Scargill of the Yorkshire miners leaders and destroy Healey's anti urged the TU movement to "kick out the working class schemes. social contract"; -44 resolutions to end social contract will be made at the NUPE national con WAGE/TAX DEAL ference in May; Last year, Healey offered a 'deal' of a -Engineers at the London Transport wage increase plus tax relief. -

Manchester's Radical History How Hyde

7/1/2021 Manchester's Radical History – Exploring Greater Manchester's Grassroots History Manchester's Radical History Exploring Greater Manchester's Grassroots History NOVEMBER 30, 2013 BY SARAH IRVING How Hyde ‘Spymasters’ looked for Commies on BBC Children’s Hour By Derek Paison Salford born folk singer and song- writer Ewan MacColl is remembered today more for his music than his agit-prop plays. But it was his political activities before the last war and his membership of the Communist Party that led to MI5 opening a file on him in the 1930s and why they kept him, and his friends, under close surveillance. Secret service papers released by the national archives, now in Ashton-under-Lyne central library, offer a clue into how British intelligence (MI5) spied on working-class folk singer Ewan MacColl and his wife playwright, Joan Lilewood, who lived at Oak Coage on Higham Lane, Hyde, Cheshire, during World War II. MI5 opened a file on James Henry Miller (MacColl’s real name) in the early 1930s when he was living in Salford. As an active Communist Party member, he had been involved in the unemployed workers’ campaigns and in the mass trespass of Kinder Scout in Derbyshire. Before enlisting in the army in July 1940, he had wrien for the radio programme Children’s Hour. In Joan Lilewood’s autobiography, she writes: “Jimmie was registered at the Labour Exchange as a motor mechanic, but he did beer busking, singing Hebridean songs to cinema queues. Someone drew Archie Harding’s aention to him and from that time on he appeared in the North Region’s features (BBC) whenever a ‘proletarian’ voice was needed.” As a BBC presenter for Children’s Hour and Communist Party member, Lilewood also came under the watch of MI5. -

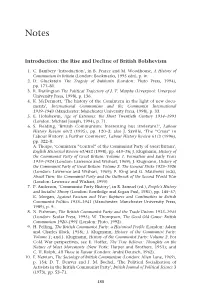

Introduction: the Rise and Decline of British Bolshevism

Notes Introduction: the Rise and Decline of British Bolshevism 1. C. Bambery ‘Introduction’, in B. Pearce and M. Woodhouse, A History of Communism In Britain (London: Bookmarks, 1995 edn), p. iv. 2. D. Gluckstein The Tragedy of Bukharin (London: Pluto Press, 1994), pp. 171–81. 3. R. Darlington The Political Trajectory of J. T. Murphy (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1998), p. 136. 4. K. McDermott, ‘The history of the Comintern in the light of new docu- ments’, International Communism and the Communist International 1919–1943 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), p. 33. 5. E. Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: the Short Twentieth Century 1914–1991 (London: Michael Joseph, 1994), p. 71. 6. S. Fielding, ‘British Communism: Interesting but irrelevant?’, Labour History Review 60/2 (1995), pp. 120–3; also J. Saville, ‘The “Crisis” in Labour History: a Further Comment’, Labour History Review 61/3 (1996), pp. 322–8. A. Thorpe, ‘Comintern “Control” of the Communist Party of Great Britain’, English Historical Review 63/452 (1998), pp. 610–36; J. Klugmann, History of the Communist Party of Great Britain: Volume 1. Formation and Early Years 1919–1924 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1969); J. Klugmann, History of the Communist Party of Great Britain: Volume 2. The General Strike 1925–1926 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1969); F. King and G. Matthews (eds), About Turn: the Communist Party and the Outbreak of the Second World War (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1990). 7. P. Anderson, ‘Communist Party History’, in R. Samuel (ed.), People’s History and Socialist Theory (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1981), pp. 145–57; K. -

North East History North North East History Volume 49 East • the Struggle Over Female Labour at the Durham Coalfield, 1914-1918 History • Fifty Years of Activism

North East History North North East History Volume 49 East • The Struggle over Female Labour at the Durham Coalfield, 1914-1918 History • Fifty Years of Activism. The NELHS in its Jubilee Year Volume 49 2018 North East History • Bevin Boys in the North East of England, 1944-48 • Phil Lenton (1946-2017), a personal appreciation • John McNair: From Tyneside Boy Orator to a Life in Socialism • Plashetts Revisited: Life and Labour in a Coal Mining Outpost • North East Germans during World War One: 49 2018 from Friend to Foe • The Radical Road: Looking Backwards and Forwards Cover illustration is copyright Trinity Mirror and reproduced courtesy of the British Library Board. The north east labour history society holds regular meetings on a wide variety of subjects. The society welcomes new members. We have an increasingly busy web-site at www.nelh.net Supporters are welcome to contribute to discussions Journal of the North East Labour History Society Volume 49 http://nelh.net/ 2018 Journal of the North East Labour History Society north east history North East Volume 49 2018 History ISSN 14743248 © 2018 NORTHUMBERLAND Printed by Azure Printing Units 1 F & G Pegswood Industrial Estate Pegswood Morpeth TYNE & Northumberland WEAR NE61 6HZ Tel: 01670 510271 DURHAM TEESSIDE Journal of the North East Labour History Society Copyright reserved on behalf of the authors and the North East Labour History Society © 2018 www.nelh.net 1 north east history Contents Note from the Editors 5 How to submit an article 7 Notes on Contributors 9 Articles: The Struggle