Natural Landscaping Sourcebook.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Landscaping: Greenacres

GGGrrreeeeeennn LLLaaannndddssscccaaapppiiinnnggg Green Landscaping: Greenacres www.epa.gov/greenacres Landscaping with native wildflowers and grasses improves the environment. Natural landscaping brings a taste of wilderness to urban, suburban, and corporate settings by attracting a variety of birds, butterflies and other animals. Once established, native plants do not need fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides or watering, thus benefiting the environment and reducing maintenance costs. Gardeners and admirers enjoy the variety of colors, shapes, and seasonal beauty of these plants. Landscaping with Great Lakes Native Plants Native Forest Plants Native Prairie Plants Native Wetland Plants Many of the plants found in the area ecosystems can also thrive in your yard, on corporate and university campuses, in parks, golf courses and on road sides. These native plants are attractive and benefit the environment. Many native plant seeds or seedlings are available from nurseries. How to Get Started There is a toolkit to promote the use of native plants. Be sure to read the article on municipal weed laws. Sustainable Landscaping, The Hidden Impacts of Gardens View this power point presentation developed by Danielle Green of the Great Lakes National Program Office and Dan Welker of EPA Region 3. The colorful slides present information on the environmental impacts to air, water, land and biodiversity of traditional landscaping and offer alternatives such as using native plants in the landscape. This presentation was developed as part of the Smithsonian Institution's Horticultural Services Division winter in-service training program. It has also been adapted for presentation at various conferences around the country. slideshow (8,620kb) And you can always talk to the wizard about commonly asked questions. -

Native Plants of East Central Illinois and Their Preferred Locations”

OCTOBER 2007 Native Plants at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Campus: A Sourcebook for Landscape Architects and Contractors James Wescoat and Florrie Wescoat with Yung-Ching Lin Champaign, IL October 2007 Based on “Native Plants of East Central Illinois and their Preferred Locations” An Inventory Prepared by Dr. John Taft, Illinois Natural History Survey, for the UIUC Sustainable Campus Landscape Subcommittee - 1- 1. Native Plants and Plantings on the UIUC Campus This sourcebook was compiled for landscape architects working on projects at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign campus and the greater headwaters area of east central Illinois.1 It is written as a document that can be distributed to persons who may be unfamiliar with the local flora and vegetation, but its detailed species lists and hotlinks should be useful for seasoned Illinois campus designers as well. Landscape architects increasingly seek to incorporate native plants and plantings in campus designs, along with plantings that include adapted and acclimatized species from other regions. The term “native plants” raises a host of fascinating scientific, aesthetic, and practical questions. What plants are native to East Central Illinois? What habitats do they occupy? What communities do they form? What are their ecological relationships, aesthetic characteristics, and practical limitations? As university campuses begin to incorporate increasing numbers of native species and areas of native planting, these questions will become increasingly important. We offer preliminary answers to these questions, and a suite of electronic linkages to databases that provide a wealth of information for addressing more detailed issues. We begin with a brief introduction to the importance of native plants in the campus environment, and the challenges of using them effectively, followed by a description of the database, online resources, and references included below. -

Neighborly Natural Landscaping: Creating Natural Environments in Residential Areas

P E N N S Y L V A N I A W I L D L I F E Neighborly Natural Landscaping: Creating Natural Environments in Residential Areas rent love affair with the closely mowed Back to the Future grass lawn dates from the nineteenth cen- omeowners across tury. Using European grazed pastures and America are changing Perceptions of lawn beauty have changed eighteenth-century formal gardens as their Hthe face of the typical American with the times. In sixteenth-century model, the Garden Clubs of America, lawn. Using gardening and land- England, the lawns of wealthy landown- the U.S. Golf Association, and the U.S. scaping practices that harmonize ers were wildflower meadows starred with Department of Agriculture embarked on with nature, they are diversifying blooms. Grasses were perceived as weeds, a campaign to landscape American lawns their plantings, improving wildlife and a garden boy’s job was to creep among with a carpet of green. With the invention habitat, and reducing lawn mower the flowers picking out the grass. Our cur- and spread of the lawn mower, the “com- noise, air and water pollution, and mon man” could have the same cropped yard waste. turf as that of an aristocrat’s mansion. Various “natural” landscapes, planned for beauty and ease of Today, at least one American town has maintenance using mainly native come full circle. In Seaside, Florida, plants, are spreading through- turfgrass is banned. Only locally native out suburbia. These landscapes species of wildflowers, shrubs, and trees include wildflower meadows, are allowed in the landscaping of private butterfly gardens, and woodland yards. -

Natural Landscaping Policy & Application

Natural Landscaping Policy & Application Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Working for You! A Fairfax County, VA, publication March 21, 2019 Natural Landscaping (NL) Defined A landscaping approach through which the aesthetic and ecological functions of landscapes installed in the built environment can be improved, and through which natural areas can be restored, by preserving and recreating land and water features and native plant communities. Sustainable landscapes are formed which protect and restore natural ecosystem components, maximize the use of native plants, remove invasive plant species, reduce turf grass, reduce or eliminate chemical inputs, protect, create, and maintain healthy soils, and retain stormwater on-site. In natural areas only locally native plant species are used to provide the greatest possible ecological benefits. In built landscapes, most of the plant cover should be composed of native plant species that support wildlife and improve environmental conditions, although non-invasive non-native plants may be selectively used where appropriate. -Fairfax County Draft NL Definition March 2019 Stormwater Planning Division 2 Fairfax County Natural Landscaping Oakton Library (Providence District) Stormwater Planning Division 3 Where Does NL Fit In? Natural Landscaping is Part of Many Related Programs • Green Infrastructure – US EPA • Environmental Site Design – VA DEQ - Stormwater Regulations • Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) • Envision – American Society of Civil Engineers • Conservation -

Conservation Landscaping Guidelines

Conservation Landscaping Guidelines The Eight Essential Chesapeake Elements of Conservation Conservation Chesapeake Landscaping Conservation Landscaping CC CC Landscaping LC Council LC Council This document can be found online at ChesapeakeLandscape.org. Published as a working draft November 2007 Special Edition revised and updated for CCLC Turning a New Leaf Conference 2013 © 2013 Chesapeake Conservation Landscaping Council ABOUT CCLC The Chesapeake Conservation Landscaping Council (CCLC) is a coalition of individuals and organizations dedicated to researching, promoting, and educating the public about conservation-based landscaping practices to benefit the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. The Council is committed to implementing best practices that result in a healthier and more beautiful environment benefiting residents and the region's biodiversity. ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION In late 2003, CCLC committee members began working on a set of materials to help define and guide conservation landscaping practices. The intended audience ranges from professionals in the landscaping field to novice home gardeners; from property managers at various types of facilities to local decision-makers. These written materials have been through many revisions, with input from professionals with diverse backgrounds. Because of the nature of the group (professionals volunteering their time), the subject matter (numerous choices of appropriate practices), and the varied audience, development of a definitive, user-friendly format was challenging. Ultimately, we intend to develop an interactive document for our website that shows examples of the Eight Elements, especially as new technology and research evolves in the future. This document has been reviewed and refined by our board members, and “put to the test” by entrants in our 2008 and 2010 landscape design contests. -

A Renaissance at Château De La Chaize

a renaissance at château de la chaize press kit - 2019 CHÂTEAU DE LA CHAIZE : FAMILY HERITAGE “If walls could talk…” Acting as liaison between a prestigious past … Château de La Chaize would tell the and a promising future, the new owner has story of countless generations. In fact, great ambition for Château de La Chaize. this stunning 17th century estate has been Committed to expanding and enhancing the home to the same family since it was first remarkable vineyards on the property - in built. The descendants of the founder, harmony with nature - Christophe Gruy has Jean-François de La Chaize d’Aix, have developed a demanding ecological approach: been its devoted caretakers for nearly three conversion of all vineyards to organic hundred and fifty years. In 2017, they passed farming, including the adoption of parcel- the estate on to the family of Christophe based farming and grape selection. His goal? Gruy, an entrepreneur and chairman of the To enable Château de La Chaize wines to Maïa Group, based in Lyon. express the character and singularity of their terroir to the fullest. 2 3 THE PEO PLE 4 THE PAST THE FOUNDER OF THE ESTATE Jean-François brother of Louis XIV’s confessor, better known as ‘Père Lachaise,’ was named the King’s de la Chaize d’Aix, Lieutenant in Beaujeu, capital of the former province of Beaujolais. He immediately fell in love with the region and in 1670, bought Château de la Douze, a medieval fortress perched on a hillside. Alas, shortly thereafter, a violent storm caused a landslide that destroyed the château. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa

Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS Volume 98 Number Article 4 1991 An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa Dean M. Roosa Department of Natural Resources Lawrence J. Eilers University of Northern Iowa Scott Zager University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright © Copyright 1991 by the Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias Part of the Anthropology Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Roosa, Dean M.; Eilers, Lawrence J.; and Zager, Scott (1991) "An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa," Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS, 98(1), 14-30. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias/vol98/iss1/4 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jour. Iowa Acad. Sci. 98(1): 14-30, 1991 An Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Guthrie County, Iowa DEAN M. ROOSA 1, LAWRENCE J. EILERS2 and SCOTI ZAGER2 1Department of Natural Resources, Wallace State Office Building, Des Moines, Iowa 50319 2Department of Biology, University of Northern Iowa, Cedar Falls, Iowa 50604 The known vascular plant flora of Guthrie County, Iowa, based on field, herbarium, and literature studies, consists of748 taxa (species, varieties, and hybrids), 135 of which are naturalized. -

Integrating Environmentally Beneficial Landscaping Into Your Environmental Management System

INTEGRATING ENVIRONMENTALLY BENEFICIAL LANDSCAPING INTO YOUR ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT SYSTEM PURPOSE AND STRUCTURE The goal of this guidance is to help Federal facilities integrate environmentally beneficial landscaping into their Environmental Management System (EMS). The document provides practical guidance, potential language, and examples of environmentally beneficial landscaping practices for each of the EMS elements, as described in the International Organization for Standardization 14001: 2004 Technical Specification and Guidance for Use (ISO 14001). The intended audience includes Federal facility staff tasked with developing an EMS and reducing the environmental impact of facility landscaping activities. The purpose of this guidance document is to assist with the addition of sustainable landscaping practices to an existing EMS or to the incorporation of sustainable landscaping into the development of an EMS. It does not, however, provide information on how to develop an entire EMS1. Section 1 provides an introductory discussion on EMSs and environmentally beneficial landscaping. The table in Section 2 walks through the key elements of an EMS and discusses the incorporation of environmentally beneficial landscaping activities into the system. Section 3 covers specific environmentally beneficial landscaping activities that can be undertaken as a part of a comprehensive EMS. I. INTRODUCTION Environmental Management Systems The Federal government is committed to reducing its environmental footprint, improving the implementation of green purchasing, and pursuing other greening the government initiatives. Federal facilities across the country are pursuing these initiatives in the context of an EMS and in response to Executive Order (EO) 13148: Greening the Government through Leadership in Environmental Management2, which mandated that all appropriate Federal facilities implement an EMS by December 2005. -

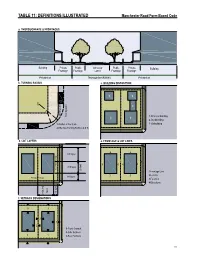

Manchester Road Redevelopment District: Form-Based Code

TaBle 11: deFiniTionS illuSTraTed manchester road Form-Based Code a. ThoroughFare & FronTageS Building Private Public Vehicular Public Private Building Frontage Frontage Lanes Frontage Frontage Private lot Thoroughfare (r.o.w.) Private lot b. Turning radiuS c. Building diSPoSiTion 3 3 2 2 1 Parking Lane Moving Lane 1- Principal Building 1 1 2- Backbuilding 1-Radius at the Curb 3- Outbuilding 2-Effective Turning Radius (± 8 ft) d. loT LAYERS e. FronTage & loT lineS 4 3rd layer 4 2 1 4 4 4 3 2nd layer Secondary Frontage 20 feet 1-Frontage Line 2-Lot Line 1st layer 3 3 Principal Frontage 3-Facades 1 1 4-Elevations layer 1st layer 2nd & 3rd & 2nd f. SeTBaCk deSignaTionS 3 3 2 1 2 1-Front Setback 2-Side Setback 1 1 3-Rear Setback 111 Manchester Road Form-Based Code ARTICLE 9. APPENDIX MATERIALS MBG Kemper Center PlantFinder About PlantFinder List of Gardens Visit Gardens Alphabetical List Common Names Search E-Mail Questions Menu Quick Links Home Page Your Plant Search Results Kemper Blog PlantFinder Please Note: The following plants all meet your search criteria. This list is not necessarily a list of recommended plants to grow, however. Please read about each PF Search Manchesterplant. Some may Road be invasive Form-Based in your area or may Code have undesirable characteristics such as above averageTab insect LEor disease 11: problems. NATIVE PLANT LIST Pests Plants of Merit Missouri Native Plant List provided by the Missouri Botanical Garden PlantFinder http://www.mobot.org/gardeninghelp/plantfinder Master Search Search limited to: Missouri Natives Search Tips Scientific Name Scientific Name Common NameCommon Name Height (ft.) ZoneZone GardeningHelp (ft.) Acer negundo box elder 30-50 2-10 Acer rubrum red maple 40-70 3-9 Acer saccharinum silver maple 50-80 3-9 Titles Acer saccharum sugar maple 40-80 3-8 Acer saccharum subsp. -

Vascular Plant Inventory and Ecological Community Classification for Cumberland Gap National Historical Park

VASCULAR PLANT INVENTORY AND ECOLOGICAL COMMUNITY CLASSIFICATION FOR CUMBERLAND GAP NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK Report for the Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories: Appalachian Highlands and Cumberland/Piedmont Networks Prepared by NatureServe for the National Park Service Southeast Regional Office March 2006 NatureServe is a non-profit organization providing the scientific knowledge that forms the basis for effective conservation action. Citation: Rickie D. White, Jr. 2006. Vascular Plant Inventory and Ecological Community Classification for Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Durham, North Carolina: NatureServe. © 2006 NatureServe NatureServe 6114 Fayetteville Road, Suite 109 Durham, NC 27713 919-484-7857 International Headquarters 1101 Wilson Boulevard, 15th Floor Arlington, Virginia 22209 www.natureserve.org National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Atlanta Federal Center 1924 Building 100 Alabama Street, S.W. Atlanta, GA 30303 The view and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. This report consists of the main report along with a series of appendices with information about the plants and plant (ecological) communities found at the site. Electronic files have been provided to the National Park Service in addition to hard copies. Current information on all communities described here can be found on NatureServe Explorer at www.natureserveexplorer.org. Cover photo: Red cedar snag above White Rocks at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park. Photo by Rickie White. ii Acknowledgments I wish to thank all park employees, co-workers, volunteers, and academics who helped with aspects of the preparation, field work, specimen identification, and report writing for this project. -

Publications of H.H

Publications of H.H. Iltis Iltis, H.H. 1945. Abundance of Selaginella in Oklahoma. Am. Fern. J. 35: 52. Iltis, H.H. 1947. A visit to Gregor Mendel’s home. Journal of Heredity 38: 162-166. Iltis, H.H. 1950. Studies in Virginia Plants I: List of bryophytes from the vicinity of Fredericksburg, Virginia. Castanea 15: 38-50. Iltis, H.H. 1953. Cleome, in Herter, G.W. Flora Illustrada del Uruguay. Fasc. 8 & 9. Iltis, H.H. 1954. Studies in the Capparidaceae I. Polanisia dodecandra (L.) DC., the correct name for Polanista graveolens Rafinesque. Rhodora 56: 64-70. Iltis, H.H. 1955. Evolution in the western North American Cleomoideae. Arkansas Academy of Science Proceedings 7: 118. (Abstract). Iltis, H.H. 1955. Capparidaceae of Nevada, in Archer, A.W. Contributions toward a Flora of Nevada, No. 35. U.S.D.A. Beltsville, MD l-24. Iltis, H.H. 1956. Studies in Virginia plants II. Rhododendron maximum in the Virginia coastal plain and its distribution in North America. Castanea 21:114-124. (Reprinted in “Wildflower”, January, 1957). Iltis, H.H. 1956. Studies in the Capparidaceae II. The Mexican species of Cleomella: Taxonomy and evolution. Madroño 13: 177-189. Iltis, H.H. 1957. Flora of Winnebago County, Illinois (Fell). Bull. Torr. Bot. Club 83: 313-314. (Book review). Iltis, H.H. 1957. Die Flechtbinse (Scirpus lacustris) (Seidler). Scientific Monthly 84: 266-267. (Book review). Iltis, H.H. 1957. Distribution and nomenclatorial notes on Galium (Rubiaceae). Rhodora 59: 38-43. Iltis, H.H. and Urban, E. 1957. Preliminary Reports on the Flora of Wisconsin No. -

Natural Landscaping Publications

April 1999 United States Region 5 Illinois, Indiana, Environmental Protection 77 West Jackson Boulevard Michigan, Minnesota, Agency Chicago, Illinois 60604 Ohio, Wisconsin Natural Landscaping Publications (800) 621-8431 www.epa.gov/greenacres/ Disclaimer: The following list does not imply any endorsement or recommendation by the Federal Government. This is not a complete list of resources. It is intended only to be an aid to those seeking initial guidance on native landscaping. Below is a partial list of resources and publications on natural landscaping. Check with your book dealer for additional resources. RESOURCES: Prairie Sun Consultants, 612 Staunton Road, Naperville, Illinois 60565-2607; (630) 983-8404. Extensive list of additional publications and a source of information. Wild Ones Natural Landscapers, Ltd., P.O. Box 23576, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53223; (630) 415-IDIG. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Fact Sheet: Landscaping With Native Plants. PUBLICATIONS: An Atlas of Biodiversity, Chicago Wilderness, The Chicago Region Biodiversity Council, 1997. “Be a Grower Not a Mower,” Gardener’s Supply Company, leaflet (EPA-420-F-96-018), Burlington, VT, 1996. Conservation Design for Subdivisions, Randall Arendt, Island Press, 1996. “Consumer Directory of Minnesota Native Wildflower/Grass Producers,” Minnesota Native Wildflower/Grass Producers Association, Route 1, Box 41, Blue Earth, MN 56013. Promotes high quality, regionally adapted native plants and seeds, lists several nurseries. Easy Care Native Plants: A Guide to Selecting and Using Beautiful American Flowers, Shrubs and Trees, Patricia A. Taylor, 1996. “Explore Minnesota Wildflowers,” Minnesota Department of Transportation, Office of Environmental Services, 3485 Hadley Avenue North, Oakdale, MN 55128. Why native plants are a "natural resource worth protecting," "native plant" defined, 3 vegetation types in Minnesota, and how to help protect native plants.