Connecticut Wildlife Sept/Oct 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext

Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium - Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext. 373 STATE CITY INSTITUTION RECIPROCITY Canada Calgary - Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Quebec - Granby Granby Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Canada Winnipeg Assiniboine Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Mexico Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon 50% Off Admission Tickets Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Alaska Seward Alaska Sealife Center 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Phoenix The Phoenix Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Off Admission Tickets Arizona Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Off Admission Tickets California Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Mateo CuriOdyssey 50% Off Admission Tickets California San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% Off Admission Tickets California Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo 50% Off Admission Tickets Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium - Reciprocal List (Updated 0 9 /22 / 2 0 2 0) Membership Department (941) 388-4441, Ext. -

Reciprocal Zoos and Aquariums

Reciprocity Please Note: Due to COVID-19, organizations on this list may have put their reciprocity program on hold as advance reservations are now required for many parks. We strongly recommend that you call the zoo or aquarium you are visiting in advance of your visit. Thank you for your patience and understanding during these unprecedented times. Wilds Members: Members of The Wilds receive DISCOUNTED or FREE admission to the AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums on the list below. Wilds members must present their current membership card along with a photo ID for each adult listed on the membership to receive their discount. Each zoo maintains its own discount policies, and The Wilds strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo. Each zoo reserves the right to limit the amount of discounts, and may not offer discounted tickets for your entire family size. *This list is subject to change at any time. Visiting The Wilds from Other Zoos: The Wilds is proud to offer a 50% discount on the Open-Air Safari tour to members of the AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums on the list below. The reciprocal discount does not include parking. If you do not have a valid membership card, please contact your zoo’s membership office for a replacement. This offer cannot be combined with any other offers or discounts, and is subject to change at any time. Park capacity is limited. Due to COVID-19 advance reservations are now required. You may make a reservation by calling (740) 638-5030. You must present your valid membership card along with your photo ID when you check in for your tour. -

Plymouth Resource Guide Community Connection

Plymouth Resource Guide Community Connection http://plymouth.k12.ct.us/guide Contents Who We are ....................................................................................................................... 1 211-Connection ................................................................................................................. 2 History of the Town of Plymouth, Terryville & Pequabuck ................................................ 2 Early Care and Education ................................................................................................... 3 Schools ............................................................................................................................... 4 Public Libraries .................................................................................................................. 6 Municipal Government and Services ................................................................................. 7 Police, Fire, and Ambulance .............................................................................................. 8 Emergency Services ........................................................................................................... 9 Health-Physical, Mental, Dental ...................................................................................... 10 Area Hospitals/Walk-in Centers....................................................................................... 12 Adult Higher Education ................................................................................................... -

The Beardsley Zoo 2012 Annual Report

2012 Annual Report Peacocks have roamed our grounds since the Zoo opened 90 years ago in 1922. ZOO DIRECTOR’S WELCOME I started volunteering at the Zoo as I will also never forget watching our an intern while in high school. And old monkey house transformed into since I was hired in 1980, the Zoo has our Rainforest Building in 1989. This been my only employer. I wouldn’t signaled a new era of growth in the have it any other way. Zoo’s history. My memories of the Zoo go back to my childhood, when my parents, Al and Louise, took me and my six sib- lings here every Sunday after church. I find it amazing that my connection with the Zoo spans 55 of the Zoo’s 90 years. It is an honor to have served as the Zoo Director since 1983 and to have been here to celebrate the Zoo’s 90th birthday with staff, board, volunteers, supporters, and guests. There is no better job in I hope that you and your family have the world than to provide safe, fun, your own warm memories of the family entertainment that also offers times you’ve spent at Connecticut’s important educational programs and Beardsley Zoo. Together we will con- protects wildlife and wild places. tinue to expand our animal exhibits, After working here for so many enhance our programming, and years, it is hard to come up with just strengthen our conservation efforts a couple memories. However, some so that future generations will have do stand out – being present for the fond recollections of their experi- Zoo’s first Amur tiger birth in 1980; ences at Connecticut’s only zoo. -

2019 Zoo New England Reciprocal List

2019 Zoo New England Reciprocal List State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone Number CANADA Calgary - Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Stephenie Motyka 403-232-9312 Quebec – Granby Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 416-392-9103 MEXICO Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 x102 Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 Every year, Zoo New England Arizona Phoenix The Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 602-914-4365 participates in a reciprocal admission Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept. 877-526-3960 program, which allows ZNE members Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 520-881-4753 free or discounted admission to other Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-661-7218 zoos and aquariums with a valid California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 membership card. Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Katharine Alexander 559-498-5938 Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 323-644-4759 Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Sue Williams 510-632-9525 x150 This list is amended specifically for Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Elisa Escobar 760-346-5694 x2111 ZNE members. If you are a member Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Brenda Gonzalez 916-808-5888 of another institution and you wish to San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Jaz Cariola 415-623-5331 visit Franklin Park Zoo or Stone Zoo, San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% Nicole Silvestri 415-753-7097 please refer to your institution's San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo 50% Snthony Teschera 408-794-6444 reciprocal list. -

RECIPROCAL LIST from YOUR ORGANIZATION and CALL N (309) 681-3500 US at (309) 681-3500 to CONFIRM

RECIPROCAL LOCAL HIGHLIGHTS RULES & POLICIES Enjoy a day or weekend trip Here are some important rules and to these local reciprocal zoos: policies regarding reciprocal visits: • FREE means free general admission and 50% off means 50% off general Less than 2 Hours Away: admission rates. Reciprocity applies to A Peoria Park District Facility the main facility during normal operating Miller Park Zoo, Bloomington, IL: days and hours. May exclude special Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. exhibits or events requiring extra fees. RECIPROCAL Niabi Zoo, Coal Valley, IL: • A membership card & photo ID are Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. always required for each cardholder. LIST Scovill Zoo, Decatur, IL: • If you forgot your membership card Peoria Zoo members receive 50% off admission. at home, please call the Membership Office at (309) 681-3500. Please do this a few days in advance of your visit. More than 2 Hours Away: • The number of visitors admitted as part of a Membership may vary depending St. Louis Zoo, St. Louis, MO: on the policies and level benefits of Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general the zoo or aquarium visited. (Example, admission and 50% off Adventure Passes. some institutions may limit number of children, or do not allow “Plus” guests.) Milwaukee Zoo, Milwaukee, WI: Peoria Zoo members receive FREE admission. • This list may change at anytime. Please call each individual zoo or aquarium Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, IL: BEFORE you visit to confirm details and Peoria Zoo members receive FREE general restrictions! admission and 10% off retail and concessions. DUE TO COVID-19, SOME FACILITIES Cosley Zoo, Wheaton, IL: MAY NOT BE PARTICIPATING. -

Born to Be Wild Children, Modern Life, and Nature

CONNECTICUT Woodlands BORN TO BE WILD CHILDREN, MODERN LIFE, AND NATURE The Magazine of the Connecticut Forest & Park Association Winter 2011 Volume 75 No. 4 About Connecticut Forest & Park Association and Connecticut Woodlands Magazine Library of Congress Children in Ledyard (above) and Norwich (below) frolic as only they know how, circa 1940. Connecting People to the Land Our mission: The Connecticut Forest & Park Association protects forests, parks, walking Annual Membership Connecticut Woodlands is a quarterly trails and open spaces for future generations by Individual $ 35 magazine published since 1936 by CFPA, the connecting people to the land. CFPA directly private, non-profit organization dedicated to involves individuals and families, educators, Family $ 50 conserving the land, trails, and natural community leaders and volunteers to enhance Supporting $ 100 resources of Connecticut. and defend Connecticut’s rich natural heritage. CFPA is a private, non-profit organization that Benefactor $ 250 Members of CFPA receive the magazine in the relies on members and supporters to carry out mail in January, April, July, and October. its mission. CFPA also publishes a newsletter several times Life Membership $ 2500 a year. Our vision: We envision Connecticut as a place of scenic beauty whose cities, suburbs, For more information about CFPA, to join or and villages are linked by a network of parks, Corporate Membership donate online, visit our newly expanded web- forests, and trails easily accessible for all people site, www.ctwoodlands.org, or call 860-346-2372. Club $ 50 to challenge the body and refresh the spirit. We picture a state where clean water, timber, farm Non-profit $ 75 Give the gift of membership in CFPA . -

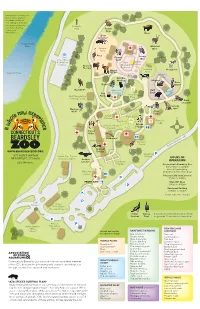

Beardsley Zoo Map Website 5-16

During your visit today, you may be photographed, videotaped or filmed. Your admission to the Zoo serves as permission for Beardsley use of your image by Park Prairie Connecticut’s Dogs Beardsley Zoo. Bison Giant Anteater* Pequonnock River Whitetail Pampas Deer Plains Barn Rhea Snowy Pygmy Owl School Bus Goat & Overflow New Reptile House Parking Chacoan England Peccary* Farmyard Learning Maned Pronghorn Circle Bunnell’s Pond Wolf* Bug Alligator Alley Goeldi’s House Monkey Alligator River Ocelot* Otter* Red Wolf* Rainforest Bald Aviary Building Eagle Red Fountain Wolf Observation Panda Plaza Learning Facility Amur Leopard* Canada Lynx* Mexican Peacock Pavilion Wolf* Amur Tiger* Jungle Picnic Grove Canteen Play Area Peacock Café African Prof. Beardsley’s Gift Shop Penguin Research Patio Camel Station Rides Hellbender* Carousel Greenhouse Carousel Annex Service Road (no exit) Spurred WWW.BEARDSLEYZOO.ORG Tortoise Overflow 1875 NOBLE AVENUE Animal Care Center Parking HOURS OF BRIDGEPORT, CT 06610 (closed to public) Andean OPERATION 203-394-6565 Condor* Sculpture Garden Connecticut’s Beardsley Zoo Daily 9:00am to 4:00pm (closed Thanksgiving, Welcome Christmas, & New Year’s Day) Center Peacock Café and Carousel 9:30am to 4:00pm FRONT GATE Main Gift Shop 9:30am to 4:00pm Rainforest Building 10:30am to 3:30pm (Hours subject to change) Park Entrance Historic Trolley Barns (Zoo maintenance) Indian Guinea Peacocks and other birds wander freely Peafowl Fowl on grounds. Please do not chase them. Hanson Administration Exploration Office Station NEW -

Miller Park Zoo Reciprocal List Zoos May Change Reciprocal Agreement Without Giving Notice

Miller Park Zoo Reciprocal List Zoos may change reciprocal agreement without giving notice. It is recommended that guests CALL AHEAD prior to visiting. The Miller Park Zoological Society (MPZS) reciprocal list is compiled of facilities accredited by the Association of Zoos & Aquariums. Zoo’s listed below are FREE to MPZS members, unless otherwise noted with the following character: * Discounted admission # Free to the public PLUS additional discount for MPZS members ALABAMA KANSAS continued OHIO Birmingham Zoo Sedgwick County Zoo, Wichita * African Safari Wildlife Park, Port Clinton * ALASKA Topeka Zoological Park Akron Zoological Park * Alaska SeaLife Center * KENTUCKY Boonshoft Museum of Discovery, Dayton ARIZONA Louisville Zoological Garden * Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden, Cincinnati * LOUISIANA Cleveland Metroparks Zoo * Phoenix Zoo * Columbus Zoo & Aquarium * Alexandria Zoo Reid Park Zoo, Tucson * The Wilds, Cumberland * BREC's Baton Rouge Zoo ARKANSAS Toledo Zoo * Little Rock Zoo * MARYLAND OKLAHOMA Maryland Zoo in Baltimore * CALIFORNIA Oklahoma City Zoo & Botanical Garden * Salisbury Zoo # Aquarium of the Bay, San Francisco * Tulsa Zoo * Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, San Pedro # MASSACHUSETTS OREGON Charles Paddock Zoo, Atascadero Buttonwood Park Zoo, New Bedford Oregon Zoo, Portland * Capron Park Zoo, Attleboro CuriOdyssey, San Mateo Wildlife Safari, Winston * Fresno Chaffee Zoo * Franklin Park Zoo, Boston * Happy Hollow Zoo, San Jose Museum of Science, Boston PENNSYLVANIA Living Desert, Palm Desert * Stone Zoo, Stoneham * Elmwood Park Zoo, Norristown * Los Angeles Zoo * MICHIGAN Erie Zoological Society Oakland Zoo * Binder Park Zoo, Battle Creek * Lehigh Valley Zoo, Schnecksville Sacramento Zoo * Children's Zoo at Celebration Square, Saginaw National Aviary, Pittsburgh * San Francisco Zoo * Detroit Zoological Society * Philadelphia Zoo * Santa Ana Zoo John Ball Zoological Garden, Grand Rapids ZOOAMERICA N. -

June 12 Special Session, Public Act No. 12-1

House Bill No. 6001 June 12 Special Session, Public Act No. 12-1 AN ACT IMPLEMENTING PROVISIONS OF THE STATE BUDGET FOR THE FISCAL YEAR BEGINNING JULY 1, 2012. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives in General Assembly convened: Section 1. Section 1 of public act 12-104 is repealed and the following is substituted in lieu thereof (Effective July 1, 2012): 2012-2013 LEGISLATIVE LEGISLATIVE MANAGEMENT Personal Services $45,260,629 Other Expenses [14,833,232] 14,983,232 Equipment 316,000 Flag Restoration 75,000 Minor Capital Improvements 265,000 Interim Salary/Caucus Offices 464,100 Connecticut Academy of Science and 100,000 Engineering Old State House 616,523 Interstate Conference Fund 380,584 New England Board of Higher Education 194,183 AGENCY TOTAL [62,505,251] 62,655,251 AUDITORS OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS House Bill No. 6001 Personal Services 11,136,456 Other Expenses 417,709 Equipment 10,000 AGENCY TOTAL 11,564,165 COMMISSION ON AGING Personal Services 251,989 Other Expenses 6,495 Equipment 1,500 AGENCY TOTAL 259,984 PERMANENT COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN Personal Services 447,419 Other Expenses 55,475 Equipment 1,500 AGENCY TOTAL 504,394 COMMISSION ON CHILDREN Personal Services 502,233 Other Expenses 29,507 AGENCY TOTAL 531,740 LATINO AND PUERTO RICAN AFFAIRS COMMISSION Personal Services 284,684 Other Expenses 33,766 AGENCY TOTAL 318,450 AFRICAN-AMERICAN AFFAIRS COMMISSION Personal Services 187,166 Other Expenses 22,663 AGENCY TOTAL 209,829 ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN AFFAIRS COMMISSION June 12 Sp. Sess., Public Act No. -

Alabama Alaska Arizona Prescott Heritage Park Zoo Arkansas

If the zoo or aquarium to which you belong has 50% in the Reciprocity column, you can expect to receive a 50% discount on admission at all the zoos and aquariums on this list (except, of course, those that are FREE TO THE PUBLIC). ALWAYS CALL AHEAD* Non AZA Zoo's Look up your zoo/aquarium. The discount you receive at other zoos/aquariums will equal what your zoo/aquarium offers to others, unless the zoo or aquarium you are visiting is free to the public. Call ahead! State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo 50% Prescott Heritage Park Zoo 50% Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 100% Big Bear City Big Bear Alpine Zoo 100% Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 100% Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Lodi Micke Grove Zoo 100% Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Exotic Feline Breeding Compounds-Feline Rosamond 100% Conservation Center Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo 50% San Mateo CuriOdyssey 100% If the zoo or aquarium to which you belong has 50% in the Reciprocity column, you can expect to receive a 50% discount on admission at all the zoos and aquariums on this list (except, of course, those that are FREE TO THE PUBLIC). ALWAYS CALL AHEAD* Non AZA Zoo's Look up your zoo/aquarium. -

Phoenix Zoo 2020 Reciprocal List January 1, 2020 Through December 31, 2020

Phoenix Zoo 2020 Reciprocal List January 1, 2020 through December 31, 2020 The following is a list of zoos and aquariums offering Phoenix Zoo Members free or reduced admission. Participation in the reciprocity program does not guarantee free admission. Each participating zoo or aquarium is responsible for determining their reciprocal admission policies. The Phoenix Zoo strongly recommends calling ahead before visiting a reciprocal zoo or aquarium to confirm benefits. This list is subject to change at any time. ALABAMA FLORIDA (CONT’D) MASSACHUSETTS • Birmingham Zoo • Zoo Miami • Buttonwood Park Zoo • ZooTampa at Lowry Park • Capron Park Zoo ALASKA • Franklin Park Zoo (Zoo New • Alaska SeaLife Center GEORGIA England) • Zoo Atlanta • Museum of Science ARIZONA • Stone Zoo (Zoo New England) • SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium, Tempe IDAHO • Reid Park Zoo, Tucson • Idaho Falls at Tautphaus Park MICHIGAN • Zoo Boise • Binder Park Zoo ARKANSAS • Detroit Zoological Society • Little Rock Zoo ILLINOIS • John Ball Zoological Garden • Cosley Zoo • Potter Park Zoological Gardens CALIFORNIA • Lincoln Park Zoo • Saginaw Children’s Zoo • Aquarium of the Bay • Miller Park Zoo • SEA Life Michigan Aquarium • Cabrillo Marine Aquarium • Peoria Zoo • Charles Paddock Zoo • Scovill Zoo MINNESOTA • CuriOdyssey • Como Park Zoo • Fresno Chaffee Zoo INDIANA • Lake Superior Zoo • Happy Hollow Zoo • Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo • Minnesota Zoo • Los Angeles Zoo • Mesker Park Zoo & Botanic Garden • Oakland Zoo • Potawatomi Zoo MISSOURI • Sacramento Zoo • Dickerson Park Zoo