Comparison Between Two Strategies for the Collection of Wheat Residue After Mechanical Harvesting: Performance and Cost Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Cereal Remains from Archaeological Sites 2Nd Edition 2006

Identification of cereal remains from archaeological sites 2nd edition 2006 Spikelet fork of the “new glume wheat” (Jones et al. 2000) Stefanie JACOMET and collaborators Archaeobotany Lab IPAS, Basel University English translation partly by James Greig CEREALS: CEREALIA Fam. Poaceae /Gramineae (Grasses) Systematics and Taxonomy All cereal species belong botanically (taxonomically) to the large family of the Gramineae (Poaceae). This is one of the largest Angiosperm families with >10 000 different species. In the following the systematics for some of the most imporant taxa is shown: class: Monocotyledoneae order: Poales familiy: Poaceae (= Gramineae) (Süssgräser) subfamily: Pooideae Tribus: Triticeae Subtribus: Triticinae genera: Triticum (Weizen, wheat); Aegilops ; Hordeum (Gerste; barley); Elymus; Hordelymus; Agropyron; Secale (Roggen, rye) Note : Avena and the millets belong to other Tribus. The identification of prehistoric cereal remains assumes understanding of different subject areas in botany. These are mainly morphology and anatomy, but also phylogeny and evolution (and today, also genetics). Since most of the cereal species are treated as domesticated plants, many different forms such as subspecies, varieties, and forms appear inside the genus and species (see table below). In domesticates the taxonomical category of variety is also called “sort” (lat. cultivar, abbreviated: cv.). This refers to a variety which evolved through breeding. Cultivar is the lowest taxonomic rank in the domesticated plants. Occasionally, cultivars are also called races: e.g. landraces evolved through genetic isolation, under local environmental conditions whereas „high-breed-races“ were breed by strong selection of humans. Anyhow: The morphological delimitation of cultivars is difficult, sometimes even impossible. It needs great experience and very detailed morphological knowledge. -

40 CFR Ch. I (7–1–19 Edition) § 180.409

§ 180.409 40 CFR Ch. I (7–1–19 Edition) dimethylphenyl)-N-(methoxyacetyl) al- Commodity Parts per anine methyl ester] and its metabolites million containing the 2,6-dimethylaniline Cattle, fat ............................................................... 0.02 moiety, and N-(2-hydroxy methyl-6- Cattle, meat byproducts ........................................ 0.02 methyl)-N-(methoxyacetyl)-alanine Corn, field, grain .................................................... 8.0 Corn, pop, grain ..................................................... 8.0 methylester, each expressed as Goat, fat ................................................................. 0.02 metalaxyl, in or on the following raw Goat, meat byproducts .......................................... 0.02 agricultural commodity: Grain, aspirated fractions ...................................... 20.0 Hog, fat .................................................................. 0.02 Hog, meat byproducts ........................................... 0.02 Commodity Parts per Horse, fat ............................................................... 0.02 million Horse, meat byproducts ........................................ 0.02 Poultry, fat ............................................................. 0.02 Papaya ................................................................... 0.1 Sheep, fat .............................................................. 0.02 Sheep, meat byproducts ....................................... 0.02 (d) Indirect or inadvertent tolerances. Sorghum, grain, grain -

Torrefaction of Oat Straw to Use As Solid Biofuel, an Additive to Organic Fertilizers for Agriculture Purposes and Activated Carbon – TGA Analysis, Kinetics

E3S Web of Conferences 154, 02004 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202015402004 ICoRES 2019 Torrefaction of oat straw to use as solid biofuel, an additive to organic fertilizers for agriculture purposes and activated carbon – TGA analysis, kinetics Szymon Szufa1, Maciej Dzikuć2 ,Łukasz Adrian3, Piotr Piersa4, Zdzisława Romanowska- Duda5, Wiktoria Lewandowska 6, Marta Marcza7, Artur Błaszczuk8, Arkadiusz Piwowar9 1 Lodz University of Technology, Faculty of Process and Environmental Engineering, Wolczanska 213, 90-924 Lodz,, Poland, [email protected] 2 University of Zielona Góra, Faculty of Economics and Management, ul. Licealna 9, 65-246 Zielona Góra, Poland, [email protected] 3 University of Kardynal Stefan Wyszyński, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Science, Dewajtis 5, 01-815 Warszawa, Poland, [email protected] 4 Lodz University of Technology, Faculty of Process and Environmental Engineering, Wolczanska 213, 90-924 Lodz,, Poland, [email protected] 5 Laboratory of Plant Ecophysiology, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz, Banacha str. 12/16, 90-131 Łódź, Poland, [email protected] 6 University of Lodz, Chemical Faculty, Tamka 13, 91-403 Łódź, Poland, [email protected] 7 AGH University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Energy and Fuels, al. Mickiewicza 30, 30- 059 Krakow, Poland, [email protected] 8 Czestochowa University of Technology, Institute of Advanced Energy Technologies, Dabrowskiego 73, 42-200, Czestochowa, Poland, [email protected] 9 Wroclaw University of Economics, Faculty of Engineering and Economics, Komandorska 118/120 , 53-345 Wrocław, Poland, [email protected] Abstract. -

CHAFF SYSTEMS - MERITS and PROBLEMS - 2L4 - by Ted Padbury, P

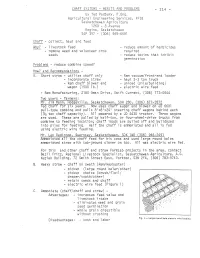

CHAFF SYSTEMS - MERITS AND PROBLEMS - 2l4 - by Ted Padbury, P. Eng. Agricultural Engineering Services, FFIB Saskatchewan Agriculture 1260 - 8 Avenue Regina, Saskatchewan S4P 3V7 - (306) 565-6591 Chaff- collect, haul and feed Why? - livestock feed - reduce amount of herbicides -remove weed andvolunteer crop required seeds - reduce toxins that inhibit germination Problems - reduce combine speed? How? arid Recommendations - A. Short straw- utilize chaff only - Rem vacuum/front-end loader · - incorporate straw - haul 2-3 ton truck - Rem chaff blower and - unload (pile/building) wagon (1500 lb. ) - electric wire feed .... Rem Manufacturtng, 2180 Oman Drive, Swift Current, (306) 773-0644 Two us·ers· - farmers: Mr. Jim Mann, Hodgeville, Saskatchewan, SOH 2BO, (306) 677-2872 Fed chaff for six years .. Now uses chaff auger and blower on JD 6601 pull-type combine and pulls 8 1 x8tx24 1 steering chaff wagons behind each . (3~ ton chaff capacHy). All powered by a JD 4430 tractor. Three wagons are used. These are pulled by half-ton, or four-wheel-drive trucks from combine to feeding location; chaff loads are pulled off and bulldozed into piles for feeding. Half the chaff is ammoniated and all is fed using electric wire feeding. t~r. Leo Redicopp, Guernsey, Saskatchewan, SOK lWO (306) 946-2491 Ammoniated all the chaff feed for his cows and used large round bales ammoniated straw with tub-ground clover on top. All was electric wire fed . .For this and other chaff and straw FarmLab projects in the area, contact Bazil Fritz, Regional Livestock Specialist, Saskatchewan Agriculture, A.G. Kuziak Building, 72 Smith Street East, Yorkton, S3N 2Y4, (306) 783-9743. -

Storage of Wet Corn Co-Products Manual

Storage of Wet Corn Co-Products 1st Edition • May 2008 A joint project of the Nebraska Corn Board and the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources Storage of Wet Corn Co-Products A joint project of the Nebraska Corn Board and the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources Agricultural Research Division University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension For more information or to request additional copies of this manual, contact the Nebraska Corn Board at 1-800-632-6761 or e-mail [email protected] Brought to you by Nebraska corn producers through their corn checkoff dollars— expanding demand for Nebraska corn and value-added corn products. STORAGE OF WET CORN CO-PRODUCTS By G. Erickson, T. Klopfenstein, R. Rasby, A. Stalker, B. Plugge, D. Bauer, D. Mark, D. Adams, J. Benton, M. Greenquist, B. Nuttleman, L. Kovarik, M. Peterson, J. Waterbury and M. Wilken Opportunities For Storage Three types of distillers grains can be produced that vary in moisture content. Ethanol plants may dry some or all of their distillers grains to produce dry distillers grains plus solubles (DDGS; 90% dry matter [DM]). However, many plants that have a market for wet distillers locally (i.e., Nebraska) may choose not to dry their distillers grains due to cost advantages. Wet distillers grains plus solubles (WDGS) is 30-35% DM. Modified wet distillers grains plus solubles (MWDGS) is 42-50% DM. It is important to note that plants may vary from one another in DM percentage, and may vary both within and across days for the moisture (i.e., DM) percentage. -

Black Chaff of Wheat Stephen N

® ® University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources Know how. Know now. G1672 (Revised December 2012) Black Chaff of Wheat Stephen N. Wegulo, Extension Plant Pathologist widely distributed bacterial disease of small grains and can Cause, symptoms, disease cycle, and management cause yield losses of up to 40 percent. of black chaff of wheat. Cause and Symptoms Black chaff is a bacterial disease of wheat common in Black chaff is caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas irrigated fields or in areas with abundant rainfall during the campestris pathovar (pv.) undulosa. The disease derives its growing season. It is also known as bacterial stripe or bacte- name from the darkened glumes of infected plants (Figure rial leaf streak. The disease also occurs on barley, oats, rye, 1A). This symptom is similar to that caused by genetic triticale, and many grasses. It is the most important and most melanism (darkening of tissue) and glume blotch incited by Stagonospora nodorum. Black chaff can be distinguished from other diseases by the appearance of cream to yellow bacterial ooze in the form of slime or viscous droplets produced on infected plant parts during wet or humid weather. This ooze appears light colored and scale-like when dry. Bands of necrotic and healthy tissue on awns (“barber’s pole” appearance) are indicative of black chaff. A dark brown to purple discoloration may appear on the stem below the head and above the flag leaf (Figure 1B). On leaves, symptoms start as small water-soaked spots or streaks that turn brown after a few days. -

Straw Mulching

STRAW MULCHING What is it? The application of straw as a protective Hand Punching: cover over seeded areas to reduce erosion and aid in A spade or shovel is used to punch straw revegetation or over bare soils that will be landscaped into the slope until all areas have straw standing later to reduce erosion. perpendicularly to the slope and embedded at least 4 inches into the slope. It should be punched about 12 When is it used? inches apart. This method is used on slopes which have been seeded and have high potential for erosion. It Roller Punching: requires some type of anchoring by matting, crimping A roller equipped with straight studs not less or other methods to prevent blowing or washing than 6 inches long, from 4 - 6 inches wide and away. approximately one inch thick is rolled over the slope. Straw mulch forms a loose layer when applied over a loose soil surface. To protect the mulch from wind drifting and being moved by water, Crimper Punching: it must be covered with a netting such as plastic or Like roller punching, the crimper has punched into the soil with a spade or roller, or by serrated disk blades about 4 - 8 inches apart which spraying it with a tacking agent. The mulch should force straw mulch into the soil. Crimping should be cover the entire seed or bare area. The mulch should done in two directions with the final pass across the extend into existing vegetation or be stabilized on all slope. sides to prevent wind or water damage which may start at the edges. -

Pet Bale Tie System for 2 Ram Baled Products

PET BALE TIE SYSTEM FOR 2 RAM BALED PRODUCTS Many industries have converted to PET strapping with the help of Samuel Strapping Systems Inc. Industry Focused Technology Driven Baling Other Samuel Areas n Waste of Expertise n OCC n Steel processors n Non-ferrous n Lumber n PET / HDPE containers n Corrugated n Tissue paper n Single stream recycling n Garments ©119094-10/16 U.S.A. - 1-800-323-4424 Canada - 1-800-607-8727 [email protected] YOUR SUCCESS IS OUR BUSINESS PACKAGING SYSTEMS GROUP 119094 P650.indd 1 2016-10-25 2:33 PM PET BALE TIE SYSTEM FOR 2 RAM BALED PRODUCTS Strapping Dispenser Products and Applications Jumbo Coil of Recycled PET Bale Tie Strapping Polyester Bail Tie System n Samuel Bale Unitizing System n All electric operation n Rugged construction n Adaptable to any twin ram baler in the field or new OEM PET Bale Tie Head n Field conversion readily accomplished in 48 hours Heat weld technology n Lower maintenance costs n Experience in extreme environments Post Installation Support n Nationwide service organization n Preventative maintenance programs n Parts depot in Chicago, IL n In-house head rebuilding program Installation Process n Technical phone support n Loaner head program n Simple installation for OEM and field retrofit n Readily compatible with the existing balers n Integration into existing automation controls n 3PH 480V 20A power supply OEM and Retro-Fit Components Patent pending strap track n Track designed for the harshest environment n Heavy gauge steel with stainless steel components n Power coated frame 112138 PET [PRINT].indd 2 2015-05-21 9:34 AM 112138 PET [PRINT].indd 3 2015-05-21 9:35 AM PET BALE TIE SYSTEM FOR 2 RAM BALED PRODUCTS Go Green with Samuel Bale Tie System Benefits of GoingGreen PET Strap vs. -

2021 BALERS BALERS 2021 HOW the BIG, ROUND BALER CHANGED the TABLE of CONTENTS: INDUSTRY THAT FEEDS and FUELS the WORLD 504 R-Series Balers Overview Pg

2021 BALERS 2021 BALERS HOW THE BIG, ROUND BALER CHANGED THE TABLE OF CONTENTS: INDUSTRY THAT FEEDS AND FUELS THE WORLD 504 R-series balers overview pg. 4 - 5 “Find a need, fill that need with a product built to last and simply build at harvesting crops for haying, feeding and bedding to help nourish a 504R Classic baler pg. 6 - 7 the best.” These words were famously spoken by Vermeer founder, healthy and vibrant food supply, as well as harvesting crop residues to 504R Signature baler pg. 8 - 9 Gary Vermeer, who made a name for himself by designing products support the biomass industry. To be sure, at Vermeer, we tip our caps 504R Premium baler pg. 10 - 11 that transformed industries and helped shape new ones altogether. to the hay producers who play such an invaluable role in feeding and Atlas™ and Atlas Pro™ control systems pg. 12 - 13 Products that proved there is always a better way to get the job done. fueling the world. 604 R-series balers overview pg. 14 - 15 It began when a local cattle producer told Gary he was getting out After nearly 50 years of round hay baling, we reinvented the way 604R Classic baler pg. 16 - 17 of the cattle business because the hay-making process was labor our producers work again. In 2017, the ZR5-1200 self-propelled 604R Signature baler pg. 18 - 19 intensive and he could no longer do it alone. That was when Gary baler — the first of its kind — marked the beginning of a new era 604R Premium baler pg. -

New Holland Big Baler Balers

BIGBALE R SERIES LARGE SQUARE BALERS BIGBALER 230 I BIGBALER 330 I BIGBALER 340 2 3 BIGBALER SERIES SMARTER. FASTER. STRONGER. It’s time to give your operation the advantages of using New Holland BigBalers. They’re the number one large square balers sold worldwide for 25 years running. NO SPEED LIMIT New Holland knows that you want to get done baling as fast as possible when the crop is ready. That’s why we’ve made the BigBaler Series faster than previous-generation balers. No speed limit? Absolutely. Baling at speeds up to 110 bales/hour, you’ll be able to get done more quickly. With the MaxiSweep™ pickup and its insatiable appetite, a 14% increase in plunger strokes per minute, the matched-width feeding that maximizes efficiency and New Holland’s proven pre-compression system, it all adds up to the highest-capacity New Holland baler ever. THE HIGHEST BALE QUALITY Square, dense bales every time with no excuses—that’s what you get with a BigBaler. Professional operators expect quality bales and New Holland has designed every part of this baler to meet the highest standards. The industry-leading pre-compression chamber ensures perfect flake formation, and the three-way density system builds solid bales. SmartFill™ bale flake formation indicators provide real-time feedback to ensure consistent performance in any windrow or field condition. It’s a competitive market and New Holland gives you the tools to make superior bales. EASE OF SERVICEABILITY Time is money. Efficient maintenance keeps your baler where it belongs—in the field. -

Oat Grower Manual: Harvest

Prairie Oat Production Manual Prairie Oat Growers Manual Back, Huvenaars, Kotylak, Kuneff, Simpson, Ziesman Prairie Oat Production Manual University of Alberta Plant Science 499 Created by: Barbara Ziesman Carly Huvenaars Joseph Back Kim Kuneff Krista Kotylak Liz Simpson Printed in 2010 Printed in Canada To view this manual, go to: www.poga.ca Prairie Oat Production Manual Disclaimer The Prairie Oat Growers Manual is a reference tool for growers of Western Canada. The authors have tried to ensure that all information is accurate and complete, however it should not be considered as the final word in all decisions. If there is a deviation from the manual you should seek advice from a trained professional. All the information provided is strictly for informational purposes and the authors make no guarantee on the use and reliance of the information. It is at your own personal risk, therefore the authors shall not be liable for any personal damages or losses or any theory based liability arising from use of the information provided. Prairie Oat Production Manual Tillage ...........................................................................26 In- Crop Yield Reducers .........................................27 Table of Contents Post Harvest: ...............................................................28 Diseases................................................. 29 Fusarium Head Blight (Scab)..............................29 Introduction ............................................1 Crown Rust (Leaf Rust) ..........................................30 -

KSU Recycling History 99 to 12

KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY RECYCLING PROGRAM THE HISTORY § The recycling program started in 1989 § We started collecting at 22 building on campus § We collected Newspaper, aluminum cans, computer paper, and white bond paper § One pick-up truck took the recycled material to Howie’s Recycling Center § In 1997 KSU started sorting material in the old dairy barn § Howie’s loaned KSU a baler so the recycled materials could be baled in 1998 § Also in 1998 the KSU Recycling Advisory Committee was established EXPANDING THE PROGRAM 1999 through 2007 1999 § Received City/University funding of $64,000 § Bought 69 Windsor outdoor recycling bins and put the bins in 23 locations around campus § Received KDHE Grant for $14,000 and bought 2 recycling trailers Provided by KDHE Grant 2000 § K-State purchases a baler § KSU begins plastic recycling § Received $5,000 grant from Pepsi Vending § Students for Environmental Action contacts KSU to start Game Day Recycling § The recycling program receives $6,000 from the National Association for Pet container Resources § $23,000 is given to KSU for student wages and educational material from the City/University Funds § Recycling Center moves from the dairy barn to the KABSU bull barn § Baled material is being picked up by Howie’s 2001 - 2002 § Initiated Pilot program – Desk-side recycling upon receiving $48,000 from City/University Funds § Desk-side recycling in 3 university buildings § Purchased a used pickup truck and fork-lift § Expanded cardboard collection by putting 13 cardboard dumpsters around campus 2004 §