Gerhardsson Light Comfort And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative 2020

Mediabase Charts Alternative 2020 Published (U.S.) -- Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 Rank Artist Title 1 TWENTY ONE PILOTS Level Of Concern 2 BILLIE EILISH everything i wanted 3 AJR Bang! 4 TAME IMPALA Lost In Yesterday 5 MATT MAESON Hallucinogenics 6 ALL TIME LOW Monsters f/blackbear 7 ABSOFACTO Dissolve 8 POWFU Coffee For Your Head 9 SHAED Trampoline 10 UNLIKELY CANDIDATES Novocaine 11 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Black Madonna 12 MACHINE GUN KELLY Bloody Valentine 13 STROKES Bad Decisions 14 MEG MYERS Running Up That Hill 15 HEAD AND THE HEART Honeybee 16 PANIC! AT THE DISCO High Hopes 17 KILLERS Caution 18 WEEZER Hero 19 TWENTY ONE PILOTS The Hype 20 WALLOWS Are You Bored Yet? 21 LOVELYTHEBAND Broken 22 DAYGLOW Can I Call You Tonight? 23 GROUPLOVE Deleter 24 SUB URBAN Cradles 25 NEON TREES Used To Like 26 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Social Cues 27 WHITE REAPER Might Be Right 28 BLACK KEYS Shine A Little Light 29 LUMINEERS Life In The City 30 LANA DEL REY Doin' Time 31 GREEN DAY Oh Yeah! 32 MARSHMELLO Happier f/Bastille 33 AWOLNATION The Best 34 LOVELYTHEBAND Loneliness For Love 35 KENNYHOOPLA How Will I Rest In Peace If... 36 BAKAR Hell N Back 37 BLUE OCTOBER Oh My My 38 KILLERS My Own Soul's Warning 39 GLASS ANIMALS Your Love (Deja Vu) 40 BILLIE EILISH bad guy 41 MATT MAESON Cringe 42 MAJOR LAZER F/MARCUS Lay Your Head On Me 43 PEACH TREE RASCALS Mariposa 44 IMAGINE DRAGONS Natural 45 ASHE Moral Of The Story f/Niall 46 DOMINIC FIKE 3 Nights 47 I DONT KNOW HOW BUT THEY.. -

Cage the Elephant Confirm Co-Headlining Tour with Beck

CAGE THE ELEPHANT CONFIRM CO-HEADLINING TOUR WITH BECK NEW ALBUM SOCIAL CUES Out April 19th Via RCA Records First Single, “Ready To Let Go” Debuts in the Top 10 at Alternative. #1 Greatest Gainer at ALT and AAA. Tour to Feature Special Guest, Spoon Photo Credit: Neil Krug (February 11, 2019) Last week, Cage The Elephant announced their return with the release of their fifth studio album, Social Cues, on April 19th via RCA Records. Today, the band confirm a co-headlining tour with Beck, who is featured on the album track “Night Running.” The Night Running Tour will begin on July 9th and includes stops at The Gorge in George, WA, Shoreline Amphitheater in Mountain View, CA, and NYC’s Forest Hill Stadium. Spoon has also been announced as a special guest on the tour and Starcrawler, Sunflower Bean and Wild Belle will open as well in select cities.Full dates below. Prior to the tour, the band is headlining Shaky Knees Festival on May 4th in Atlanta. Tickets go on sale to the general public beginning Friday, February 15th at 10am local time at LiveNation.com. Citi is the official presale credit card for the tour. As such, Citi cardmembers will have access to purchase presale tickets beginning Tuesday, February 12th at 10:00 a.m. local time until Thursday, February 14th at 10:00 p.m. local time through Citi’s Private Pass program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Beck and Cage The Elephant have partnered up with PLUS1 and $1 from every ticket sold will be donated back into each city they are playing in, supporting local food security initiatives as they work towards ending hunger in their communities. -

Cage the Elephant's Social Cues Is out Today on Rca

CAGE THE ELEPHANT’S SOCIAL CUES IS OUT TODAY ON RCA RECORDS WATCH THEIR PERFORMANCE ON LATE NIGHT WITH STEPHEN COLBERT HERE CAGE THE ELEPHANT AND BECK THE NIGHT RUNNING CO-HEADLINING TOUR BEGINS THIS JULY (New York —April 19, 2019) Today, Cage The Elephant has released their fifth studio album, Social Cues, out now on RCA Records. Fans can stream/purchase the album HERE. Social Cues was produced by John Hill (Santigold, Florence + The Machine, Portugal. The Man, tUnE- yArDs), recorded at Battle Tapes Recording, Blackbird Studio and Sound Emporium in Nashville and The Village Recording Studio in Los Angeles. It was mixed by Tom Elmhirst and mastered by Randy Merrill in New York City. To mark the album’s release, the band appeared on Late Night With Stephen Colbert last night, performing their single, “Ready To Let Go.” Watch their performance HERE. “Ready To Let Go,” remains #1 at Alternative Radio in both the US and Canada, marking the band’s 8th Alternative #1. Cage The Elephant has achieved more #1s at the format than any band this decade. Photo Credit: Neil Krug This summer, Cage The Elephant and Beck will head out on their co-headlining, The Night Running Tour in North America. Spoon will open all dates as a special guest with additional support from Starcrawler, Sunflower Bean and Wild Belle in select cities. The two artists collaborated on the single “Night Running,” that appears on Social Cues. Full dates below. Tickets are on sale now at LiveNation.com. Beck and Cage The Elephant have partnered up with PLUS1 and $1 from every ticket sold will be donated back into each city they are playing in, supporting local food security initiatives as they work towards ending hunger in their communities. -

Title Artist a BARENAKED LADIES a TEAM, the ED SHEERAN

Library QuickPrint Music Test 2019 A-Z 2020 Title Artist A BARENAKED LADIES A TEAM, THE ED SHEERAN ABACAB GENESIS ABC JACKSON 5 ABOUT A GIRL (Unplugged) NIRVANA ABRACADABRA STEVE MILLER BAND ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE COUNTING CROWS ACCIDENTS WILL HAPPEN ELVIS COSTELLO ADAM RAISED A CAIN BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN ADDICTED TO LOVE ROBERT PALMER ADIA SARAH McLACHLAN ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME COLDPLAY ADVENTURES OF RAIN DANCE MAGGIE, THE RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS AEROPLANE RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS AFTER MIDNIGHT J.J. CALE AFTER MIDNIGHT ERIC CLAPTON AGAIN LENNY KRAVITZ AGAIN TONIGHT JOHN MELLENCAMP AGAINST THE WIND BOB SEGER AH LEAH DONNIE IRIS AIN'T EVEN DONE WITH THE NIGHT JOHN MELLENCAMP AIN'T NO MAN AVETT BROTHERS AIN'T NO REST FOR THE WICKED CAGE THE ELEPHANT AIN'T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERS AIN'T TOO PROUD TO BEG ROLLING STONES AIN'T WASTIN' TIME NO MORE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND AIRPLANE WIDESPREAD PANIC AJA STEELY DAN ALABAMA GETAWAY GRATEFUL DEAD ALISON ELVIS COSTELLO ALIVE PEARL JAM ALIVE AND KICKING SIMPLE MINDS ALL ALONG THE WATCHTOWER JIMI HENDRIX ALL APOLOGIES (UNPLUGGED) NIRVANA ALL DAY & ALL OF THE NIGHT KINKS ALL FOR YOU SISTER HAZEL ALL I WANNA DO SHERYL CROW ALL I WANT TOAD THE WET SPROCKET ALL I WANT IS YOU U2 ALL MIXED UP CARS 1/17/2020 1:24:43 PM Page: 1 Library QuickPrint Music Test 2019 A-Z 2020 Title Artist ALL MY FRIENDS REVIVALISTS ALL MY LOVE LED ZEPPELIN ALL NIGHT LONG JOE WALSH ALL RIGHT GUY TODD SNIDER ALL SHE WANTS TO DO IS DANCE DON HENLEY ALL STAR SMASH MOUTH ALL THE GIRLS LOVE ALICE ELTON JOHN ALL THE THINGS SHE SAID SIMPLE MINDS ALL -

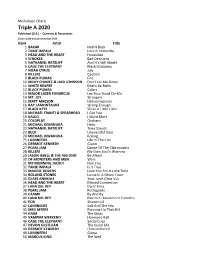

Triple a 2020

Mediabase Charts Triple A 2020 Published (U.S.) -- Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 Rank Artist Title 1 BAKAR Hell N Back 2 TAME IMPALA Lost In Yesterday 3 HEAD AND THE HEART Honeybee 4 STROKES Bad Decisions 5 NATHANIEL RATELIFF And It's Still Alright 6 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Black Madonna 7 NOAH CYRUS July 8 KILLERS Caution 9 BLACK PUMAS Fire 10 MILKY CHANCE & JACK JOHNSON Don't Let Me Down 11 WHITE REAPER Might Be Right 12 BLACK PUMAS Colors 13 MAJOR LAZER F/MARCUS Lay Your Head On Me 14 MT. JOY Strangers 15 MATT MAESON Hallucinogenics 16 RAY LAMONTAGNE Strong Enough 17 BLACK KEYS Shine A Little Light 18 MICHAEL FRANTI & SPEARHEAD I Got You 19 KALEO I Want More 20 COLDPLAY Orphans 21 MICHAEL KIWANUKA Hero 22 NATHANIEL RATELIFF Time Stands 23 BECK Uneventful Days 24 MICHAEL KIWANUKA Rolling 25 LUMINEERS Life In The City 26 DERMOT KENNEDY Giants 27 PEARL JAM Dance Of The Clairvoyants 28 KILLERS My Own Soul's Warning 29 JASON ISBELL & THE 400 UNIT Be Afraid 30 OF MONSTERS AND MEN Wars 31 MY MORNING JACKET Feel You 32 TAME IMPALA Is It True 33 MAGGIE ROGERS Love You For A Long Time 34 ROLLING STONES Living In A Ghost Town 35 GLASS ANIMALS Your Love (Deja Vu) 36 HEAD AND THE HEART Missed Connection 37 LANA DEL REY Doin' Time 38 PEARL JAM Retrograde 39 CAAMP By And By 40 LANA DEL REY Mariners Apartment Complex 41 EOB Shangri-LA 42 LUMINEERS Salt And The Sea 43 MEG MYERS Running Up That Hill 44 HAIM The Steps 45 VAMPIRE WEEKEND Harmony Hall 46 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Social Cues 47 DEVON GILFILLIAN The Good Life 48 DERMOT KENNEDY -

Rick Case Arena

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The urC rent NSU Digital Collections 3-12-2019 The urC rent Volume 29 : Issue 24 Nova Southeastern University Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper NSUWorks Citation Nova Southeastern University, "The urC rent Volume 29 : Issue 24" (2019). The Current. 686. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper/686 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the NSU Digital Collections at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Current by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Student-Run Newspaper of Nova Southeastern University March 12, 2019 | Vol. 29, Issue 24 | nsucurrent.nova.edu Features Arts & Entertainment Sports Opinions Visit these beautiful destinations How art can impact your Should we be paying college It’s time we do something about before it’s too late education athletes to play? red tide P. 4 P. 6 P. 8 P. 10 #BalanceforBetter - NSU’s International Women’s Day Colloquium By: Madelyn Rinka Co-Editor-in-Chief The colloquium gives students and student [men] when we tell them these are the facts. “A workplace that addresses organizations the opportunity to prepare and Many young men feel like we’re blaming present research posters surrounding gender them… but we’re not blaming [an individual], gender issues or stereotypes will, issues in their academic fields, in honor of even if his great-great-great-great grandfather International Women’s Day. did it, he didn’t know any better,” explained in turn, have a more “In the United States, International Sims. -

Cage the Elephant

CAGE THE ELEPHANT Die Grammy-Gewinner live in Deutschland Am 28. Februar 2020 im DOCKS in Hamburg, Pop-Punks SWMRS als Support dabei Am 19. April erschien mit ›Social Cues‹ das mittlerweile fünfte Studioalbum von Cage The Elephant. Nachdem die US-Amerikaner aus Kentucky im Juni für eine exklusive Show in Berlin waren, verkünden sie jetzt neue Live-Termine im kommenden Jahr. Zu erleben gibt’s die Grammy-Gewinner zwischen dem 26. und 28. Februar in der Live Music Hall Köln, im Astra Berlin und im Hamburger Docks. Mit als Support haben sie SWMRS aus Kalifornien – feinster Punk Rock, gegründet 2004 als Schulband von Joey Armstrong, Sohn des Green Day Frontmanns. Sie sind aktuell eine der aufregendsten Live-Bands, wenn es um Garage-Rock geht. Ihren Sound haben Cage The Elephant über die Jahre mit einem feinen Gespür für zeitlose Songs zu einer überzeugenden Mischung aus Indie und Alternative ausgefeilt. 2007 spielen die Brüder Matt (Gesang) und Brad Shultz (Gitarre) zusammen mit ihrer Band beim South-By-South-West Festival in Texas und hinterlassen einen prägenden Eindruck, der vor allem nach England schwappt und dort für großes Interesse sorgt. Kurzerhand ziehen Cage The Elephant ins pulsierende London. Was folgt ist eine Zeit, in der die Truppe fast täglich in einem anderen Club spielt, meist vor überschaubarem Publikum. Doch all die Arbeit und Aufopferung zahlt sich letztlich aus: 2008 veröffentlichen Cage The Elephant ihr gleichnamiges Debütalbum. Die dritte Singleauskopplung ›Ain’t No Rest For The Wicked‹ bringt den erhofften Erfolg und der Song landet in den Top 40 der UK-Charts. -

Cage the Elephant Confirmados Dia 10 De Julho

COMUNICADO DE IMPRENSA 12/11/2019 NOS apresenta a 10 de julho CAGE THE ELEPHANT CONFIRMADOS DIA 10 DE JULHO NO NOS ALIVE'20 Os norte-americanos Cage The Elephant são a mais recente confirmação a juntar-se ao cartaz do NOS Alive’20. Na bagagem o grupo conta com quatro aclamados discos e trazem até ao Palco NOS, dia 10 de julho, o mais recente trabalho “Social Cues” editado no passado mês de abril. O álbum de estreia da banda, lançado em 2008, apresenta vários singles de sucesso em destaque nas principais rádios, como “Ain’t No Rest for the Wicked”, e ganhou imediata atenção internacional, que os projetou para a tabela da Billboard Alternative Songs. No entanto, 2013 foi o ano de ascensão do grupo com o lançamento do terceiro disco de estúdio, “Melophobia”, nomeado em 2015 para um Grammy na categoria “Best Alternative Music Album”. Oriundos de Kentucky, os Cage The Elephant são Matt Shultz (vocalista), Brad Shultz (guitarra), Jared Champion (bateria), Daniel Tichenor (baixo), Nick Bockrath (guitarra) e Matthan Minster (teclado). O NOS Alive regressa ao Passeio Marítimo de Algés nos dias 09, 10 e 11 de julho de 2020. Os bilhetes estão à venda nos pontos de venda oficiais. Mais informações em www.nosalive.com. Artistas confirmados: Billie Eilish, Cage The Elephant, Caribou, Da Weasel, Hobo Johnson and The Lovemakers, Taylor Swift,Two Door Cinema Club e Wolf Parade Imagens Informação Bilhetes NOS LPM Edifício Campo Grande, Carla Alves | Alexandra Amorim 1 Rua Ator António Silva, 9, Piso 2, Lisboa [email protected] | [email protected] www.nos.pt T 930 475 455 | 91 940 92 92 | 218 508 110 Sobre a NOS A NOS é o maior grupo de comunicações e entretenimento em Portugal. -

Retarded in a Manner Analogous to the Teaching of Reading and Writing

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 793 EC 003 658 By- Edmonson, Barbara; And Others Social Inference Training of Retarded Adolescents at the Pre-Vocational Level. Kansas Univ., Kansas City. Medical Center. Spons Agency-Vocational Rehabilitation Alministration (DHEW),. Washington, D.C. Pub Date 68 Grant-RD-1388-P Note-171p. EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC-$8.65 Descriptors-*Attitudes, *Behavior, Behavior Change, Behavior Rating Scales, Comprehension Development, Educable Mentally Handicapped, *ExceptionalChild Research,Institutionalized (Persons), Interpersonal Competence, Junior High School Students, *Mentally Handicapped, Prevocational Education, Social Attitudes, Socially Maladjusted, Student Evaluation, Test Reliability, *Ter:ts, Test Validity Identifiers-Test of Social Infeeence, 151 The relationship between the difficulty with which the retarded adolescent decodes visual social cues and the appropriateness of his social behaviorwas the basis of a study to determine whether social cue decoding could be taught the retardedin a manner analogous to the teaching of reading and writing, with beneficial behavioral results. The Test of Social Inference (TSDwas developed and used as the before and after criterion of social comprehension. During four trials. 11 classesofretardedadolescentsattheprevocationallevelwere provided experimental lessons designed to promote social awareness daily for periods of from 6 to 10 weeks as a part of their special education. Two control classeswere provided placebo materials and five were provided contrast materials to supplement their usual curricula, and one control class had no change made in its usual program. All pupils were given social behavioral rtings by their teachers before and after the periods of treatment. The association between social comprehension and social behavior was confirmed by significant correlations between the pupils' TSI scores and their social behavioral ratings (p=.001). -

Plink: "Thin Slices" of Music Author(S): Carol L

Plink: "Thin Slices" of Music Author(s): Carol L. Krumhansl Source: Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 27, No. 5 (June 2010), pp. 337-354 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/mp.2010.27.5.337 . Accessed: 04/04/2013 18:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.84.126.222 on Thu, 4 Apr 2013 18:14:32 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Music2705_01 5/13/10 3:41 PM Page 337 Thin Slices of Music 337 PLINK:“THIN SLICES” OF MUSIC CAROL L. KRUMHANSL presenting listeners with short (300 and 400 ms) clips from Cornell University popular songs. In order to study effects of release date, the songs were taken from the 1960’s through the 2000’s. SHORT CLIPS (300 AND 400 MS), TAKEN FROM POPULAR Listeners were asked to name the artist and title and indi- songs from the 1960’s through the 2000’s, were presented cate their confidence in the identifications. -

Cage the Elephant & Introduces 2020 “Best New Artist”

Austin City Limits Showcases One of Rock’s Biggest Live Acts: Cage The Elephant & Introduces 2020 “Best New Artist” Grammy Nominee Tank and the Bangas New Episode Premieres January 23 on PBS Austin, TX—January 23, 2020—Austin City Limits (ACL) spotlights thrilling live bands in a new installment featuring rock giants Cage The Elephant, one of music’s biggest live acts. The hour also introduces a 2020 “Best New Artist” GRAMMY nominee, New Orleans breakout act Tank and the Bangas. The broadcast premieres Saturday, January 25 at 8pm CT/9pm ET on PBS. The episode will be available to music fans everywhere, streaming online the next day beginning Sunday, January 26 @10am ET at pbs.org/austincitylimits. Providing viewers a front-row seat to the best in live performance for a remarkable 45 years, the program airs weekly on PBS stations nationwide (check local listings for times) and full episodes are made available online for a limited time at pbs.org/austincitylimits immediately following the initial broadcast. Viewers can visit acltv.com for news regarding future tapings, episode schedules and select live stream updates. The show's official hashtag is #acltv. Hailing from Kentucky, the Nashville-based six-piece Cage The Elephant perform tracks from their acclaimed fifth album Social Cues, alongside career highlights in a stellar, hit-filled set. Charismatic lead singer/live wire Matt Shultz takes the stage in a signature makeshift outfit: elbow-length blue gloves, blue tights adorned with women’s lace underwear, headphones and goggles. A wardrobe rack and a trunk filled with props sit onstage amidst the amplifiers, as the shape-shifting frontman changes outfits with each song. -

Classic Obs' #3

LE LÉGENDAIRE FRONTMAN ET COMPOSITEUR DE CREED EST DE RETOUR LTD DIGIPAK | LTD 1-LP GATEFOLD VINYL | DIGITAL AVEC UN NOUVEL ALBUM SOLO INTROSPECTIF ET CAPTIVANT. OUT 12.07. DELUXE BOX-SET EXCLUSIVELY AVAILABLE AT NAPALMRECORDS.COM! LES CHAMPIONS DU HEAVY ALLEMAND CRÉENT UN VÉRITABLE MONDE POST-APOCALYPTIQUE… LTD DIGIPAK | LTD 1-LP GATEFOLD VINYL | DIGITAL OUT 28.06. DELUXE BOX-SET EXCLUSIVELY AVAILABLE AT NAPALMRECORDS.COM! Key: CTP Template: CD_INL4 COLOURS No text area Compact Disc Inside Inlay (clearcase) CYAN MAGENTA Customer Wednesday 13 YELLOW Bleed Clear Spine Catalogue No. BLACK Trim Area Job Title Calling All Corpses Fold Bloody Hammers booste sa musique à grands renforts LTD DIGIPAK | LTD 1-LP GATEFOLD VINYL | DIGITAL d’hymnes goth n’ roll ! OUT 28.06. OH HIROSHIMA OSCILLATION OUT 14.06. CD | GATEFOLD VINYL | DIGITAL Puissant, énergique, planant… Le post rock dans ce qu’il a1 de17.8 meilleur ! OUT 26.07. LTD DIGIPAK | LTD 2-LP GATEFOLD VINYL | DIGITAL /NAPALMRECORDS /NAPALMRECORDSOFFICIAL visit our online store with music and merch /NAPALMRECORDS /NAPALMRECORDS WWW.NAPALMRECORDS.COM Clear Tray Disc Area 6.5 138 6.5 PLEASE NOTE THIS TEMPLATE HAS BEEN CREATED USING SPECIFIC CO-ORDINATES REQUIRED FOR COMPUTER TO PLATE IMAGING AND IS NOT TO BE ALTERED, MOVED OR THE DOCUMENT SIZE CHANGED. ALL DIMENSIONS ARE IN MILLIMETRES. BLEED ALLOWANCE OF 3MM ON TRIMMED EDGES edito CLASSIC OBS’ N°3 - MAI / JUIN 2019 Du riff hi-fi dans l’air Directeur de la publication Tyler Bryant, texan relocalisé à Nashville, et ses trois « Shakedown » au look de saltimbanques désar- Charles Provost gentés Graham Whitford (fils de Brad Whitford, guitare), Noah Denney (basse) et Caleb Crosby (batterie) Responsable de la rédaction ont un sacerdoce que d’aucuns pourraient trouver ingrat : faire encore battre le cœur des amoureux du Jean-Christophe Baugé rock n’roll, sans passer pour des dépassés.