Volcanic Hazards Presentation – Teacher’S Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information on Natural Disasters Part- I Introduction

Information on Natural Disasters Part- I Introduction Astrology is the one that gave us the word ‘disaster’. Many believe that when the stars and planets are in malevolent position in our natal charts bad events or bad things would happen. Everyone one of us loves to avoid such bad things or disasters. The disaster is the impact of both natural and man-made events that influence our life and environment that surrounds us. Now as a general concept in academic circles, the disaster is a consequence of vulnerability and risk. The time often demands for appropriate reaction to face vulnerability and risk. The vulnerability is more in densely populated areas where if, a bad event strikes leads to greater damage, loss of life and is called as disaster. In other sparely populated area the bad event may only be a risk or hazard. Developing countries suffer the greatest costs when a disaster hits – more than 95 percent of all deaths caused by disasters occur in developing countries, and losses due to natural disasters are 20 times greater as a percentage of GDP in developing countries than in industrialized countries. A disaster can leads to financial, environmental, or human losses. The resulting loss depends on the capacity of the population to support or resist the disaster. The term natural has consequently been disputed because the events simply are not hazards or disasters without human involvement. Types of disasters Any disaster can be classified either as ‘Natural’ or ‘man-made’. The most common natural disasters that are known to the man kind are hailstorms, thunderstorm, very heavy snowfall, very heavy rainfalls, squalls, gale force winds, cyclones, heat and cold waves, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, floods, and droughts which cause loss to property and life. -

Volcanic Gases

ManuscriptView metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Click here to download Manuscript: Edmonds_Revised_final.docx provided by Apollo Click here to view linked References 1 Volcanic gases: silent killers 1 2 3 2 Marie Edmonds1, John Grattan2, Sabina Michnowicz3 4 5 6 3 1 University of Cambridge; 2 Aberystwyth University; 3 University College London 7 8 9 4 Abstract 10 11 5 Volcanic gases are insidious and often overlooked hazards. The effects of volcanic gases on life 12 13 6 may be direct, such as asphyxiation, respiratory diseases and skin burns; or indirect, e.g. regional 14 7 famine caused by the cooling that results from the presence of sulfate aerosols injected into the 15 16 8 stratosphere during explosive eruptions. Although accounting for fewer fatalities overall than some 17 18 9 other forms of volcanic hazards, history has shown that volcanic gases are implicated frequently in 1910 small-scale fatal events in diverse volcanic and geothermal regions. In order to mitigate risks due 20 2111 to volcanic gases, we must identify the challenges. The first relates to the difficulty of monitoring 22 2312 and hazard communication: gas concentrations may be elevated over large areas and may change 2413 rapidly with time. Developing alert and early warning systems that will be communicated in a timely 25 2614 fashion to the population is logistically difficult. The second challenge focuses on education and 27 2815 understanding risk. An effective response to warnings requires an educated population and a 2916 balanced weighing of conflicting cultural beliefs or economic interests with risk. -

Review of Local and Global Impacts of Volcanic Eruptions and Disaster Management Practices: the Indonesian Example

geosciences Review Review of Local and Global Impacts of Volcanic Eruptions and Disaster Management Practices: The Indonesian Example Mukhamad N. Malawani 1,2, Franck Lavigne 1,3,* , Christopher Gomez 2,4 , Bachtiar W. Mutaqin 2 and Danang S. Hadmoko 2 1 Laboratoire de Géographie Physique, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, UMR 8591, 92195 Meudon, France; [email protected] 2 Disaster and Risk Management Research Group, Faculty of Geography, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia; [email protected] (C.G.); [email protected] (B.W.M.); [email protected] (D.S.H.) 3 Institut Universitaire de France, 75005 Paris, France 4 Laboratory of Sediment Hazards and Disaster Risk, Kobe University, Kobe City 658-0022, Japan * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This paper discusses the relations between the impacts of volcanic eruptions at multiple- scales and the related-issues of disaster-risk reduction (DRR). The review is structured around local and global impacts of volcanic eruptions, which have not been widely discussed in the literature, in terms of DRR issues. We classify the impacts at local scale on four different geographical features: impacts on the drainage system, on the structural morphology, on the water bodies, and the impact Citation: Malawani, M.N.; on societies and the environment. It has been demonstrated that information on local impacts can Lavigne, F.; Gomez, C.; be integrated into four phases of the DRR, i.e., monitoring, mapping, emergency, and recovery. In Mutaqin, B.W.; Hadmoko, D.S. contrast, information on the global impacts (e.g., global disruption on climate and air traffic) only fits Review of Local and Global Impacts the first DRR phase. -

Volcanic Hazards • Washington State Is Home to Five Active Volcanoes Located in the Cascade Range, East of Seattle: Mt

CITY OF SEATTLE CEMP – SHIVA GEOLOGIC HAZARDS Volcanic Hazards • Washington State is home to five active volcanoes located in the Cascade Range, east of Seattle: Mt. Baker, Glacier Peak, Mt. Rainier, Mt. Adams and Mt. St. Helens (see figure [Cascades volcanoes]). Washington and California are the only states in the lower 48 to experience a major volcanic eruption in the past 150 years. • Major hazards caused by eruptions are blast, pyroclastic flows, lahars, post-lahar sedimentation, and ashfall. Seattle is too far from any volcanoes to receive damage from blast and pyroclastic flows. o Ash falls could reach Seattle from any of the Cascades volcanoes, but prevailing weather patterns would typically blow ash away from Seattle, to the east side of the state. However, to underscore this uncertainty, ash deposits from multiple pre-historic eruptions have been found in Seattle, including Glacier Peak (less than 1 inch) and Mt. Mazama/Crater Lake (amount unknown) ash. o The City of Seattle depends on power, water, and transportation resources located in the Cascades and Eastern Washington where ash is more likely to fall. Seattle City Light operates dams directly east of Mt. Baker and in Pend Oreille County in eastern Washington. Seattle’s water comes from two reservoirs located on the western slopes of the Central Cascades, so they are outside the probable path of ashfall. o If heavy ash were to fall over Seattle it would create health problems, paralyze the transportation system, destroy many mechanical objects, endanger the utility networks and cost millions of dollars to clean up. Ash can be very dangerous to aviation. -

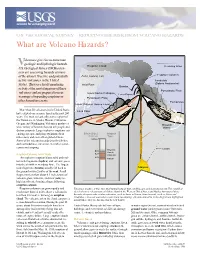

What Are Volcano Hazards?

USG S U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY—REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS What are Volcano Hazards? olcanoes give rise to numerous Vgeologic and hydrologic hazards. Eruption Cloud Prevailing Wind U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scien- tists are assessing hazards at many Eruption Column of the almost 70 active and potentially Ash (Tephra) Fall active volcanoes in the United Landslide States. They are closely monitoring Acid Rain (Debris Avalanche) Bombs activity at the most dangerous of these volcanoes and are prepared to issue Vent Pyroclastic Flow Lava Dome Collapse Lava Dome warnings of impending eruptions or Pyroclastic Flow other hazardous events. Fumaroles Lahar (Mud or Debris Flow) More than 50 volcanoes in the United States Lava Flow have erupted one or more times in the past 200 years. The most volcanically active regions of the Nation are in Alaska, Hawaii, California, Oregon, and Washington. Volcanoes produce a Ground wide variety of hazards that can kill people and Water destroy property. Large explosive eruptions can endanger people and property hundreds of Silica (SiO2) Magma miles away and even affect global climate. Content Type Some of the volcano hazards described below, 100% such as landslides, can occur even when a vol- cano is not erupting. Rhyolite Crack 68 Dacite 63 Eruption Columns and Clouds Andesite 53 An explosive eruption blasts solid and mol- Basalt ten rock fragments (tephra) and volcanic gases into the air with tremendous force. The largest rock fragments (bombs) usually fall back to Magma the ground within 2 miles of the vent. Small fragments (less than about 0.1 inch across) of volcanic glass, minerals, and rock (ash) rise 0 high into the air, forming a huge, billowing eruption column. -

A Database of the Economic Impacts of Historical Volcanic Eruptions M Goujon, Hajare El Hadri, Raphael Paris

A database of the economic impacts of historical volcanic eruptions M Goujon, Hajare El Hadri, Raphael Paris To cite this version: M Goujon, Hajare El Hadri, Raphael Paris. A database of the economic impacts of historical volcanic eruptions. 2021. hal-03186803 HAL Id: hal-03186803 https://hal.uca.fr/hal-03186803 Preprint submitted on 31 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. C E N T R E D 'ÉTUDES ET DE RECHERCHES SUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT INTERNATIONAL SÉRIE ÉTUDES ET DOCUMENTS A database of the economic impacts of historical volcanic eruptions Hajare El Hadri Michaël Goujon Raphaël Paris Études et Documents n° 14 March 2021 To cite this document: El Hadri H., Goujon M., Paris R. (2021) “A database of the economic impacts of historical volcanic eruptions ”, Études et Documents, n°14, CERDI. CERDI POLE TERTIAIRE 26 AVENUE LÉON BLUM F- 63000 CLERMONT FERRAND TEL. + 33 4 73 17 74 00 FAX + 33 4 73 17 74 28 http://cerdi.uca.fr/ Études et Documents n°14, CERDI, 2021 The authors Hajare El Hadri Post-doctoral researcher, Université Clermont -

Volcanic Hazards at Mount Shasta, California

U.S. Geological Survey / Department of the Interior Volcanic Hazards at Mount Shasta, California Volcanic Hazards at Mount Shasta, California by Dwight R. Crandell and Donald R. Nichols Cover: Aerial view eastward toward Mount Shasta and the community of Weed, California, located on deposits of pyroclastic flows formed about 9,500 years ago. The eruptions of Mount St. Helens, Washington, in 1980 served as a reminder that long-dormant volcanoes can come to life again. Those eruptions, and their effects on people and property, also showed the value of having information about volcanic hazards well in advance of possible volcanic activity. This pam phlet about Mount Shasta provides such information for the public, even though the next eruption may still be far in the future. Locating areas of possible hazard and evaluating them is one of the roles of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). If scientists recognize signs of an impending eruption, responsi ble public officials will be notified and they may advise you' of the need to evacuate certain areas or to take other actions to protect yourself. Your cooperation will help reduce the danger to yourself and others. This pamphlet concerning volcanic hazards at Mount Shasta was prepared by the USGS with the cooperation of the Division of Mines and Geology and the Office of Emergency Services of the State of California. An eruption of Mount Shasta could endanger your life and the lives of your family and friends. To help you understand and plan for such a danger, this pamphlet describes the kinds of volcanic activity that have occurred in the past, shows areas that could be affected in the future, and suggests ways of reducing the risk to life or health if the volcano does erupt. -

Volcanic Hazards

have killed more than 5,000 people. Two important points are demonstrated by this. The first is that the most deadly eruptions are generally pyroclastic: lava flows are rarely a main cause of death. The second is that it is not always the biggest eruptions that cause the most deaths. Even quite small eruptions can be major killers – for example the 1985 eruption of Ruiz, which resulted in 5 the second largest number of volcanic fatalities of the twentieth century. Sometimes volcanoes kill people even when they are not erupting: Iliwerung 1979 (a landslide, not associated with an Volcanic hazards eruption, that caused a tsunami when it entered the sea) and Lake Nyos 1986 (escaping gas) being examples of death by two different non-eruptive mechanisms. In this chapter you will learn: • about the most devastating volcanic eruptions of historic times Some of the causes of death listed in Table 5.1 may need further • about the wide variety of ways in which eruptions can cause death elaboration. Famine, for example, is a result of crop failure and/ and destruction (including by triggering a tsunami). or the loss of livestock because of fallout, pyroclastic flows or gas poisoning. It is often accompanied by the spread of disease In previous chapters I dealt with the different types of volcano as a result of insanitary conditions brought about by pollution that occur and the ways in which they can erupt. The scene is now of the water supply. In the modern world it is to be hoped that set to examine the hazards posed to human life and well-being international food aid to a stricken area would prevent starvation by volcanic eruptions. -

Smartworld.Asia Specworld.In

Smartworld.asia Specworld.in LECTURE NOTES ON DISASTER MANAGEMENT III B. Tech I semester (JNTU-R13) smartworlD.asia Smartzworld.com 1 jntuworldupdates.org Smartworld.asia Specworld.in UNIT-1 Environmental hazard' is the state of events which has the potential to threaten the surrounding natural environment and adversely affect people's health. This term incorporates topics like pollution and natural disasters such as storms and earthquakes. Hazards can be categorized in five types: 1. Chemical 2. Physical 3. Mechanical 4. Biological 5. Psychosocial What are chemical hazards and toxic substances? Chemical hazards and toxic substances pose a wide range of health hazards (such as irritation, sensitization, and carcinogenicity) and physical hazards (such as flammability, corrosion, and reactivity). This page provides basic information about chemical hazards and toxic substances in the workplace. While not all hazards associated with every chemical and toxic substance are addressed here, we do provide relevant links to other pages with additional information about hazards and methods to control exposure in the workplace. A natural disaster is a major adverse event resulting from natural processes of the Earth; examples includesmartworlD.asia floods, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, tsunamis, and other geologic processes. A natural disaster can cause loss of life or property damage, and typically leaves some economic damage in its wake, the severity of which depends on the affected population's resilience, or ability to recover.[1] An adverse event will not rise to the level of a disaster if it occurs in an area without vulnerable population.[2][3][4] In a vulnerable area, however, such as San Francisco, an earthquake can have disastrous consequences and leave lasting damage, requiring years to repair. -

Super-Eruptions: Global Effects and Future Threats

The Jemez Mountains (Valles Caldera) super-volcano, New Mexico, USA. Many super-eruptions have come from volcanoes that are either hard to locate or not very widely known. An example is the Valles Caldera in the Jemez Mountains, near to Santa Fe and Los Alamos, New Mexico, USA. The caldera is the circular feature (centre) in this false-colour (red=vegetation) Landsat image, which shows an area about 80 kilometres across of the region in North-Central New Mexico. The collapsed caldera is 24 kilometres in diameter and is the result of two explosive super- eruptions 1.6 and 1.1 million years ago (i.e., 500,000 years apart). All rocks in the photo below are part of the 250 metre thick deposits of the older of the two super- eruptions at the Valles Caldera. It’s not a question of “if” – it’s a question of “when…” “Many large volcanoes on Earth are capable of explosive eruptions much bigger than any experienced by humanity over historic time. Such volcanoes are termed super-volcanoes and their colossal eruptions super-eruptions. Super-eruptions are different from other hazards such as earthquakes, tsunamis, storms or fl oods in that – like the impact of a large asteroid or comet – their environmental effects threaten global civilisation.” “Events at the smaller-scale end of the super-eruption size spectrum are quite common when compared with the frequency of other naturally occurring devastating phenomena such as asteroid impacts. The effects of a medium-scale super- eruption would be similar to those predicted for the impact of an asteroid one kilometre across, but super-eruptions of this size are still fi ve to ten times more likely to occur within the next few thousand years than an impact.” “Although at present there is no technical fi x for averting super-eruptions, improved monitoring, awareness-raising and research-based planning would reduce the suffering of many millions of people.” 1 Executive summary Some very large volcanoes are capable Problems such as global warming, of colossal eruptions with global impacts by asteroids and comets, rapid consequences. -

Artifacts and Natural Disasters in Nigeria: the Riverine Experiences

International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Research Vol. 4 No. 8 2018 ISSN: 2545-5303 www.iiardpub.org Artifacts and Natural Disasters in Nigeria: The Riverine Experiences Eluozo Collins Department of curriculum and Instructional Technology (Science Education Option) Faculty of Education Ignatius Ajuru University of Education, Port Harcourt, Nigeria [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Nigeria is a country endowed with enormous natural resources located in the Western Sub- Sahara of Africa. The country is conceived to have existed before 1100 years before Christ. The country Nigeria and its environs is characterized by multiethnic diversity and diverse history of religious beliefs. The country was cohered by the British missionaries and it was granted independence in 1960 and a republic in 1963. Nigeria’s land mass is featured by dry, costal and swampy ecosystem. According to the holy bible, God used disasters to punish and cleanse the planet earth due to man’s disobedience and till date mankind has not found solutions to various types of artifact and natural disasters that have besieged the planet. How these disasters erupts, unlash mayhems and devastate the earth was the focal point of the study. The paper discussed lithosphere disasters, artifacts, atmospheric and hydrosphere disasters, there various impacts on the riverine communities and disasters benefits as well losses. The paper concluded with recommendations that could foster purposive solutions that can help in containing these catastrophes against mankind. Keywords: Nigeria, Disasters, Bible. Planet, NEMA, Artifact, Natural, Flood, Fire, Lithosphere, Hydrosphere, Atmosphere, Earthquake, Sinkholes, Terrorism, Volcanic, Eruption. Cataclysmic, Storms, Temperature. Introduction Nigeria is a country located in the sub-Saharan of the West Africa, endowed with all natural resources for human existence. -

Detecting Gas-Rich Hydrothermal Vents in Ngozi Crater Lake Using

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Detecting gas-rich hydrothermal vents in Ngozi Crater Lake using integrated exploration tools Received: 16 May 2019 Egbert Jolie1,2,3 Accepted: 7 August 2019 Gas-rich hydrothermal vents in crater lakes might pose an acute danger to people living nearby due Published: xx xx xxxx to the risk of limnic eruptions as a result of gas accumulation in the water column. This phenomenon has been reported from several incidents, e.g., the catastrophic Lake Nyos limnic eruption. CO2 accumulation has been determined from a variety of lakes worldwide, which does not always evolve in the same way as in Lake Nyos and consequently requires a site-specifc hazard assessment. This paper discusses the current state of Lake Ngozi in Tanzania and presents an efcient approach how major gas-rich hydrothermal feed zones can be identifed based on a multi-disciplinary concept. The concept combines bathymetry, thermal mapping of the lake foor and gas emission studies on the water surface. The approach is fully transferable to other volcanic lakes, and results will help to identify high-risk areas and develop suitable monitoring and risk mitigation measures. Due to the absence of a chemical and thermal stratifcation of Lake Ngozi the risk of limnic eruptions is rather unlikely at present, but an adapted monitoring concept is strongly advised as sudden CO2 input into the lake could occur as a result of changes in the magmatic system. Intense gas emissions at the geosphere-atmosphere interface is a common process in volcanically and tectoni- 1 cally active regions.