Japan, Nissan and the Ghosn Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

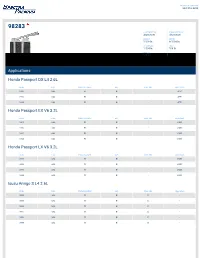

Applications Honda Passport DX L4 2.6L Honda Passport EX V6 3.2L

TECHNICAL SUPPORT 888-910-8888 98283 CORE MATERIAL TANK MATERIAL Aluminum Aluminum HEIGHT WIDTH 5-3/8 In. 6-1/16 In. THICKNESS INLET 1-1/4 In. 5/8 In. OUTLET 5/8 In. Applications Honda Passport DX L4 2.6L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1996 GAS FI N - 4ZE1 1995 GAS FI N - 4ZE1 1994 GAS FI N - 4ZE1 Honda Passport EX V6 3.2L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1997 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1996 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1995 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1994 GAS FI N - 6VD1 Honda Passport LX V6 3.2L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1997 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1996 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1995 GAS FI N - 6VD1 1994 GAS FI N - 6VD1 Isuzu Amigo S L4 2.6L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1994 GAS FI N E - 1993 GAS FI N E - 1992 GAS FI N E - 1991 GAS FI N E - 1990 GAS FI N E - 1989 GAS FI N E - Isuzu Amigo S L4 2.3L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1993 GAS CARB N L - 1992 GAS CARB N L - 1991 GAS CARB N L - 1990 GAS CARB N L - 1989 GAS CARB N L - Isuzu Amigo XS L4 2.6L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. ENG. VIN ENG. DESG 1994 GAS FI N E - 1993 GAS FI N E - 1992 GAS FI N E - 1991 GAS FI N E - 1990 GAS FI N E - 1989 GAS FI N E - Isuzu Amigo XS L4 2.3L YEAR FUEL FUEL DELIVERY ASP. -

Contacts in Japan Contacts in Asia

TheDirectoryof JapaneseAuto Manufacturers′ WbrldwidePurchaslng ● Contacts ● トOriginalEqulpment ● トOriginalEqulpment Service トAccessories トMaterials +RmR JA払NAuTOMOBILEMANUFACTURERSAssocIATION′INC. DAIHATSU CONTACTS IN JAPAN CONTACTS IN ASIA OE, Service, Accessories and Material OE Parts for Asian Plants: P.T. Astra Daihatsu Motor Daihatsu Motor Co., Ltd. JL. Gaya Motor 3/5, Sunter II, Jakarta 14350, urchasing Div. PO Box 1166 Jakarta 14011, Indonesia 1-1, Daihatsu-cho, Ikeda-shi, Phone: 62-21-651-0300 Osaka, 563-0044 Japan Fax: 62-21-651-0834 Phone: 072-754-3331 Fax: 072-751-7666 Perodua Manufacturing Sdn. Bhd. Lot 1896, Sungai Choh, Mukim Serendah, Locked Bag No.226, 48009 Rawang, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia Phone: 60-3-6092-8888 Fax: 60-3-6090-2167 1 HINO CONTACTS IN JAPAN CONTACTS IN ASIA OE, Service, Aceessories and Materials OE, Service Parts and Accessories Hino Motors, Ltd. For Indonesia Plant: Purchasing Planning Div. P.T. Hino Motors Manufacturing Indonesia 1-1, Hinodai 3-chome, Hino-shi, Kawasan Industri Kota Bukit Indah Blok D1 No.1 Tokyo 191-8660 Japan Purwakarta 41181, Phone: 042-586-5474/5481 Jawa Barat, Indonesia Fax: 042-586-5477 Phone: 0264-351-911 Fax: 0264-351-755 CONTACTS IN NORTH AMERICA For Malaysia Plant: Hino Motors (Malaysia) Sdn. Bhd. OE, Service Parts and Accessories Lot P.T. 24, Jalan 223, For America Plant: Section 51A 46100, Petaling Jaya, Hino Motors Manufacturing U.S.A., Inc. Selangor, Malaysia 290 S. Milliken Avenue Phone: 03-757-3517 Ontario, California 91761 Fax: 03-757-2235 Phone: 909-974-4850 Fax: 909-937-3480 For Thailand Plant: Hino Motors Manufacturing (Thailand)Ltd. -

Download Chapter 154KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 10 178 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 10 RYOICHI NAKAGAWA 179 RYOICHI NAKAGAWA 1913–1998 BY TREVOR O.JONES DR. RYOICHI NAKAGAWA, retired executive managing director, Nissan Motor Company, Ltd., died in Tokyo, Japan, on July 30, 1998. Dr. Nakagawa was born in Tokyo on April 27, 1913, and received his B.Sc. degree in mechanical engineering and his Ph.D. in engineering from the prestigious University of Tokyo. Not only was Dr. Nakagawa one of the nicest and kindliest people I have ever met, but he was also one of the most aristocratic. My wife and I fondly remember Dr. Nakagawa coming to our home in Birmingham, Michigan, and spending a lot of time with our children teaching them origami and Japanese children’s games. This no doubt had an influence on our daughter, Bronwyn, who majored in Japanese at the University of Michigan. Although I originally met Dr. Nakagawa through our mutual interests in automobile design, we both came from the aerospace and defense industries. It was through these earlier defense-related experiences that we calmly discussed the implications of the United States dropping the two atom bombs on Japan. Our discussions were both interesting and objective and, most important, each of us understood the other’s position. Dr. Nakagawa devoted his sixty-year career to engineering in a wide array of disciplines. He started his career as an aircraft engine designer in 1936 at Nakajima Aircraft Company and stayed at this company until the end of World War II. -

Suzuki Announces FY2019 Vehicle Recycling Results in Japan

22 June 2020 Suzuki Announces FY2019 Vehicle Recycling Results in Japan Suzuki Motor Corporation has today announced the results of vehicle recycling for FY2019 (April 2019 to March 2020) in Japan, based on the Japan Automobile Recycling Law*1. In line with the legal mandate, Suzuki is responsible for promoting appropriate treatment and recycling of automobile shredder residue (ASR), airbags, and fluorocarbons through recycling fee deposited from customers. Recycling of these materials are appropriately, smoothly, and efficiently conducted by consigning the treatment to Japan Auto Recycling Partnership as for airbags and fluorocarbons, and to Automobile Shredder Residue Recycling Promotion Team*2 as for ASR. The total cost of recycling these materials was 3,640 million yen. Recycling fees and income generated from the vehicle-recycling fund totalled 4,150 million yen, contributing to a net surplus of 510 million yen. For the promotion of vehicle recycling, Suzuki contributed a total of 370 million yen from the above net surplus, to the Japan Foundation for Advanced Auto Recycling, and 20 million yen for the advanced recycling business of the Company. For the mid-and long-term, Suzuki continues to make effort in stabilising the total recycling costs. Moreover, besides the recycling costs, the Company bears 120 million yen as management-related cost of Japan Automobile Recycling Promotion Center and recycling-related cost of ASR. The results of collection and recycling of the materials are as follows. 1. ASR - 60,388.3 tons of ASR were collected from 450,662 units of end-of-life vehicles - Recycling rate was 96.7%, exceeding the legal target rate of 70% set in FY2015 since FY2008 2. -

Honda Cr-V Honda Element Honda Odyssey Honda Pilot

55336 ACURA CL SERIES HONDA CR-V ACURA INTEGRA HONDA ELEMENT ACURA MDX HONDA ODYSSEY ACURA RL SERIES HONDA PILOT ACURA TL SERIES HONDA PRELUDE HONDA ACCORD ISUZU OASIS 12/04/1213 A. Locate the vehicles taillight wiring harness behind the rear bumper. The harness will have connectors similar to those on the T-connector harness and can be found in the following positions: Passenger Cars: 1. Open the trunk and remove the plastic screw that secures the trunk liner on the passengers side of the trunk. Peel back the trunk liner to expose the vehicles harness. 1996-1999 Isuzu Oasis 1995-1998 Honda Odyssey: 1. Remove the rear access panel located inside the van directly behind the driver’s side taillight to expose the vehicle wiring harness. 1999-2004 Honda Odyssey: 1. Open rear tailgate and remove driver’s side cargo bracket screw. 2. Carefully pull back trim panel to expose vehicle’s wiring harness. 1997-2001 Honda CR-V: 1. Remove the rear driver’s side speaker and cover. The speaker will be held in place with three screws. The vehicle connector will be secured to the pseaker wires. 2002-2006 Honda CR-V: 1. Open the rear tailgate and remove the cargo door on the floor. Remove the storage container from the vehicle floor and set aside. 2. Remove the rear threshold and driver’s side cargo bracket screw. Remove the cargo screw on the driver’s side trim panel. Remove the cargo bracket by unscrewing bolt fron vehicle floor. 3. Carefully pry trim panel away from vehicle body. -

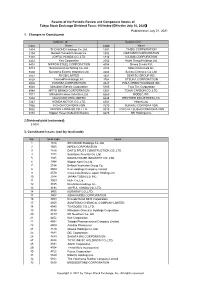

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

“We Want to Be Bold. Nissan Should Be Bold.” - Shiro Nakamura, Senior Vice President & Chief Creative O Cer, Nissan Motor Company, Ltd

INNOVATION MADE BOLD N EW YORK CITY BEYOND ADVERTISING AGENCY “We want to be bold. Nissan should be bold.” - Shiro Nakamura, Senior Vice President & Chief Creative Ocer, Nissan Motor Company, Ltd. We would like to thank the CEO of Nissan, Carlos Ghosn, for the opportunity to create a campaign that reflects the innovation of the Nissan Company. President Table of Contents Jana Cudiamat General Managers 1 Acknowledgements Cheyenne Logan Tracy Solorzano 2 Our Inspiration Account Planning Olivia Holland-LaForte, Executive Director Mathilde Perot 3 Executive Summary Danielle Tsimberg Creative Justine Dungo, Executive Director 4-8 Research Jennifer Wong, Associate Director Jacqueline Alves Frank LoBello 9-17 Creative Devyn Silverstein A special thank you to Dr. Martin Topol, Professor Phyllis Toss, Ms. Nisha Lalchandani, John Szalyga, and Jonathan Viano. Media 18-19 Media Maria Loreto, Executive Director Melissa Escobar Mark Kazinec • Throughout the plans book, the term, Multicultural Millennial, will 20-26 Strategy Integration Lissette Martinez at times be abbreviated using the acronym, MCM. Drew Mihalik • Hispanic American, African American, and Chinese American Katie Tymvios will be represented with the following acronyms, respectively: 27-28 Dealership Experience PR/Promotions HA, AA, and CA. Brittany Hallberg, Executive Director • Throughout the plans book, vehicle personality is italicized to 29 Visual Summary Ashley Kaywood convey each vehicles’ bold persona that we designed for the Alina Vorontsova campaign. Dealership Experience 30 Flowchart Christina Danza, Executive Director Our deepest appreciation to Navindra Guman Measurement 31 Professor Conrad Nankin & Dr. Larry Chiagouris Elizabeth Pawlowski & Evaluation for their guidance and endless dedication. Future 32 Recommendations ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 2 OUR INSPIRATION Executive Summary Tailoring a Brand Perception to Match an Exciting Lifestyle Nissan is a brand with a bold mission to provide exciting and innovative vehicles for “At our core, we didn't know what all. -

Vehicle Brochure

Nissan Intelligent Mobility moves you one step ahead. In cars that feel like an extension 2021 of you, helping you see more and sense more, reacting with you, and sometimes even ® for you. Nissan Intelligent Mobility is about a better future – moving through life with VERSA greater confidence, excitement and connection to the world around you. information. 26 State laws may apply. Review before using. 27 Genuine Nissan Accessories are covered by Nissan’s Limited Warranty on Genuine Nissan Replacement Parts, Genuine NISMO® S-Tune Parts, and Genuine Nissan Accessories for the longer of 12 months/12,000 miles (whichever occurs first) or the remaining period under the 3-year/36,000-mile (whichever occurs first) Nissan New Vehicle Limited Warranty. Terms and conditions apply. See dealer, Warranty Information Booklet, or parts.NissanUSA.com for details. 28 Brake Assist cannot prevent all collisions and may not provide warning or braking in all conditions. Driver should monitor traffic conditions and brake as needed to prevent collisions. See Owner’s Manual for safety information. 29 Vehicle Dynamic Control cannot prevent collisions due to abrupt steering, carelessness, or dangerous driving techniques. It should remain on when driving, except when freeing the vehicle from mud or snow. See Owner’s Manual for safety information. 30 Roadside Assistance available for a period of 36 months/36,000 miles from the date the vehicle is delivered to the first retail buyer or otherwise put into use, whichever is earlier. Apple CarPlay® is a registered trademark of Apple, Inc. Bluetooth® is a registered trademark of Bluetooth SIG, Inc. -

Hino Motors, Ltd. Representative: Satoshi Ogiso, President, Member

July 29, 2021 Company Name: Hino Motors, Ltd. Representative: Satoshi Ogiso, President, Member of the Board (Code Number: 7205 TSE, 1st Section, NSE, 1st Section) Contact Person: Hiroshi Hashimoto Operating Officer Public Affairs Dept. Phone: (042) 586-5494 Supply of Vehicles Manufactured by Isuzu Motors Limited for North America The Board of Directors of Hino Motors Ltd. (“Hino”) has approved a plan to obtain vehicles manufactured by Isuzu Motors Limited (“Isuzu”) for the North American market. In this regard, Hino hereby announces that its consolidated subsidiary, Hino Motors Sales U.S.A. Inc., has entered into an agreement with Isuzu’s consolidated subsidiary, Isuzu North America Corporation, with respect to the supply of the vehicles. 1. Rationale Hino is obtaining vehicles from Isuzu in order to quickly resume North American supply of Class 4 and Class 5 model vehicles*1 impacted by the production pause at Hino’s North America plants.*2 *1 Total vehicle weight: Class 4 - 14,001 to 16,000 pounds, Class 5 - 16,001 to 19,500 pounds *2 Please refer to the timely disclosure announcement titled “Production Pause at Hino’s North America Plants”, dated December 23, 2020 2. Overview Hino will obtain the “N series” diesel trucks manufactured by Isuzu and sell those trucks as Hino branded “S series” trucks to Hino dealers in the United States and Canada. 3. Expected Schedule Hino plans to commence the supply of the “S series” trucks in both U.S. and Canadian markets in October 2021. 4. Future outlook The impact of this agreement on the consolidated financial results for the current fiscal year is expected to be minor. -

Comparative Reflections on the Carlos Ghosn Case and Japanese Criminal Justice

Volume 18 | Issue 24 | Number 2 | Article ID 5523 | Dec 15, 2020 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Comparative Reflections on the Carlos Ghosn Case and Japanese Criminal Justice Bruce E. Aronson, David T. Johnson he would have fared better under American law, nor is it obvious that justice would have Abstract: The arrest and prosecution of Nissan been better realized. executive Carlos Ghosn, together with his dramatic flight from Japan, have focused Key words: criminal justice, white-collar unprecedented attention on Japan’s criminal crime, Japan, United States, Carlos Ghosn, justice system. This article employs comparison hostage justice, conviction rates, confessions, with the United States to examine issues in plea bargaining Japanese criminal justice highlighted by the Ghosn case. The criminal charges and procedures used in Ghosn’s case illustrate several serious weaknesses in Japanese criminal justice—including the problems of prolonged detention and interrogation without a defense attorney that have been characterized as “hostage justice.” But in comparative perspective, the criminal justice systems in Japan and the U. S. have some striking similarities. Most notably, both systems rely on coercive means to obtain admissions of guilt, and both systems have high conviction rates. The American counterpart to Japan’s use of high-pressure tactics to obtain confessions is a system of plea bargaining in which prosecutors use the threat of a large “trial tax” Carlos Ghosn in Detention in Japan (a longer sentence for defendants who insist upon their right to a trial and are then convicted) to obtain guilty pleas. An apples-to- apples comparison also indicates that Japan’s Introduction “99% conviction rate” is not the extreme outlier that it is often said to be. -

![Mission [P3] 801Kb](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5774/mission-p3-801kb-725774.webp)

Mission [P3] 801Kb

NISSAN MOTOR COMPANY ANNuAl RePORT 2013 03 contents corporate face time MANAGEMENT MESSAGES nissan power 88 performance corporate governance 1935 Datsun 14 1969 Datsun Z S30 1989 Infiniti Q45 G50 In April 1935, less than two years after Nissan's establishment, the The S30 was the first-generation Z car. It was created by transforming a light open-top In autumn 1989 Nissan launched its new Infiniti brand in the United States with the Q45 first small “Datsun 14” passenger car rolled off the assembly line at sports car into a Grand Touring (GT) car with a closed body, reflecting the changing as its flagship model. Presented as a “Japan original,” this large, luxurious sedan was an the Yokohama Plant. The plant had just been newly built as Japan's trends of the times. The graceful styling of the S30 with its lower, longer and wider expression of Japan’s unique aesthetics and detailed attention to passenger comfort. first mass production facility for automobiles. dimensions captivated car fans the world over. The Q45 attracted considerable attention in the target U.S. market, as well as in its home country of Japan. 1982 March/Micra K10 The March embodied a variety of concepts unprecedented in Japanese cars. For example, a model life of approximately ten years 1957 Datsun 1000 Sedan 210 was envisioned from the outset. Outstanding levels of basic Datsun 1000 Sedan (210) was released in 1957. The following year performance were attained though extensive weight savings. And the it was entered in the 1958 Australian Rally, an exceptionally grueling styling was intended to have timeless appeal. -

ABANDONED VEHICLE in Accordance with Section 32-13-1, Code of Alabama 1975, Notice Is Hereby Given to the Owners, Lienholders An

ABANDONED VEHICLE In accordance with Section 32-13-1, Code of Alabama 1975, notice is hereby given to the owners, lienholders and other interested parties that the following described abandoned vehicle will be sold at public auction for cash to the highest bidder 9:00 am, OCTOBER 9, 2018 at Mobile Police Impound; 1251 Virginia Street, Lot B; Mobile, AL 36604. 2008 BMW 750 IS WBAHL83518DT12734 2001 BUICK LESABRE 1G4HP54K914142716 1994 BUICK LESABRE 1G4HR52L1RH432166 1997 BUICK PARK AVENUE 1G4CW52K6V4601173 2007 CADILLAC CTS 1G6DM57T270114436 2007 CADILLAC DTS 1G6KD57Y47U111937 2002 CADILLAC ESCALADE 1GYEC63T62R217146 1996 CADILLAC FLEETWOOD 1G6DW52P1TR714939 2002 CHEVROLET CAMARO 2G1FP22K422107868 1995 CHEVROLET CAMARO 2G1FP22P4S2179830 2005 CHEVROLET AVALANCHE 3GNEK12Z55G227180 1998 CHEVROLET GMT-400 1GCGC33RXWF020361 1995 CHEVROLET GMT-400 1GCEK14K2SZ131530 2013 CHEVROLET IMPALA 2G1WC5E31D1224351 2006 CHEVROLET IMPALA 2G1WB58K669274804 2004 CHEVROLET IMPALA 2G1WH52K849221882 2002 CHEVROLET MALIBU 1G1ND52J52M510586 2005 CHEVROLET SILVERADO 1GCEC14X05Z328659 2003 CHEVROLET SILVERADO 1GCEC14V63Z337037 2003 CHEVROLET SILVERADO 1GCEC14T93Z359435 2001 CHEVROLET SILVERADO 2GCEC19VX11220429 2004 CHEVROLET TRAILBLAZER 1GNDS13S242319755 2002 CHEVROLET TRAILBLAZER 1GNDS13S522239797 2000 CHEVROLET VENTURE 1GNDX03E6YD116156 2010 CHRYSLER 300 2C3CA5CV4AH289903 1999 CHRYSLER 300 2C3HE66G7XH234528 2000 CHRYSLER CONCORDE 2C3HD36J5YH103225 2005 CHRYSLER SEBRING 1C3EL66R25N611149 2008 DODGE CHARGER 2B3KA43R88H274255 2000 DODGE NEON 1B3ES46C6YD698466 1999