C:\Documents and Settings\Parul\Desktop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microsoft Outlook

Emails pertaining to Gateway Pacific Project For April 2013 From: Jane (ORA) Dewell <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, April 01, 2013 8:12 AM To: '[email protected]'; Skip Kalb ([email protected]); John Robinson([email protected]); Brian W (DFW) Williams; Cyrilla (DNR) Cook; Dennis (DNR) Clark; Alice (ECY) Kelly; Loree' (ECY) Randall; Krista Rave-Perkins (Rave- [email protected]); Jeremy Freimund; Joel Moribe; 'George Swanaset Jr'; Oliver Grah; Dan Mahar; [email protected]; Scott Boettcher; Al Jeroue ([email protected]); AriSteinberg; Tyler Schroeder Cc: Kelly (AGR) McLain; Cliff Strong; Tiffany Quarles([email protected]); David Seep ([email protected]); Michael G (Env Dept) Stanfill; Bob Watters ([email protected]); [email protected]; Jeff Hegedus; Sam (Jeanne) Ryan; Wayne Fitch; Sally (COM) Harris; Gretchen (DAHP) Kaehler; Rob (DAHP) Whitlam; Allen E (DFW) Pleus; Bob (DFW) Everitt; Jeffrey W (DFW) Kamps; Mark (DFW) OToole; CINDE(DNR) DONOGHUE; Ginger (DNR) Shoemaker; KRISTIN (DNR) SWENDDAL; TERRY (DNR) CARTEN; Peggy (DOH) Johnson; Bob (ECY) Fritzen; Brenden (ECY) McFarland; Christina (ECY) Maginnis; Chad (ECY) Yunge; Douglas R. (ECY) Allen; Gail (ECY) Sandlin; Josh (ECY) Baldi; Kasey (ECY) Cykler; Kurt (ECY) Baumgarten; Norm (ECY) Davis; Steve (ECY) Hood; Susan (ECY) Meyer; Karen (GOV) Pemerl; Scott (GOV) Hitchcock; Cindy Zehnder([email protected]); Hallee Sanders; [email protected]; Sue S. PaDelford; Mary Bhuthimethee; Mark Buford ([email protected]); Greg Hueckel([email protected]); Mark Knudsen ([email protected]); Skip Sahlin; Francis X. Eugenio([email protected]); Joseph W NWS Brock; Matthew J NWS Bennett; Kathy (UTC) Hunter; ([email protected]); Ahmer Nizam; Chris Regan Subject: GPT MAP Team website This website will be unavailable today as maintenance is completed. -

City of Spokane, Official, Gazette, November 23, 2016

City of Spokane, Washington Statement of City Business, including a Summary of the Proceedings of the City Council Volume 106 N OVEMBER 23, 2016 Issue 47 Part I of II MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL MAYOR DAVID A. CONDON COUNCIL PRESIDENT BEN STUCKART COUNCIL MEMBERS: BREEAN BEGGS (DISTRICT 2) MIKE FAGAN (DISTRICT 1) LORI KINNEAR (DISTRICT 2) CANDACE MUMM (DISTRICT 3) KAREN STRATTON (DISTRICT 3) AMBER WALDREF (DISTRICT 1) The Official Gazette INSIDE THIS ISSUE (USPS 403-480) Published by Authority of City Charter Section 39 MINUTES 1271 The Official Gazette is published weekly by the Office of the City Clerk HEARING NOTICES 1284 5th Floor, Municipal Building, Spokane, WA 99201-3342 Official Gazette Archive: ORDINANCES 1286 http://www.spokanecity.org/services/documents (ORDINANCES, JOB OPPORTUNITIES To receive the Official Gazette by e-mail, send your request to: & NOTICES FOR BIDS CONTINUED IN [email protected] PART II OF THIS ISSUE) 1271 O FFICIAL G AZETTE, SPOKANE, WA N OVEMBER 23, 2016 The Official Gazette USPS 403-480 0% Advertising Periodical postage paid at Minutes Spokane, WA POSTMASTER: MINUTES OF SPOKANE CITY COUNCIL Send address changes to: Monday, November 14, 2016 Official Gazette Office of the Spokane City Clerk BRIEFING SESSION 808 W. Spokane Falls Blvd. 5th Floor Municipal Bldg. The Briefing Session of the Spokane City Council held on the above date was called to Spokane, WA 99201-3342 order at 3:30 p.m. in the Council Chambers in the Lower Level of the Municipal Building, 808 West Spokane Falls Boulevard, Spokane, Washington. Subscription Rates: Within Spokane County: $4.75 per year Roll Call Outside Spokane County: On roll call, Council President Stuckart, Council Members Beggs, Fagan, Kinnear, Mumm, $13.75 per year Stratton, and Waldref were present. -

Section 9202 Joint Information Center Manual

Section 9202 Joint Information Center Manual Communicating during Environmental Emergencies Northwest Area: Washington, Oregon, and Idaho able of Contents T Section Page 9202 Joint Information Center Manual ........................................ 9202-1 9202.1 Introduction........................................................................................ 9202-1 9202.2 Incident Management System.......................................................... 9202-1 9202.2.1 Functional Units .................................................................. 9202-1 9202.2.2 Command ............................................................................ 9202-1 9202.2.3 Operations ........................................................................... 9202-1 9202.2.4 Planning .............................................................................. 9202-1 9202.2.5 Finance/Administration....................................................... 9202-2 9202.2.6 Mandates ............................................................................. 9202-2 9202.2.7 Unified Command............................................................... 9202-2 9202.2.8 Joint Information System .................................................... 9202-3 9202.2.9 Public Records .................................................................... 9202-3 9202.3 Initial Information Officer – Pre-JIC................................................. 9202-3 9202.4 Activities of Initial Information Officer............................................ 9202-4 -

Starting an LPFM Radio Station

Starting an LPFM Radio Station Written and compiled by Kai Aiyetoro, Director of LPFM Edited by Kathryn Washington, Director of Operations Funded by The Ford Foundation and The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation The National Federation of Communit5r Broadcasters - 197O Broadway Suite 1000, Oakland, CA 94612 Table of Contents What is Community Radio? 2 Starting a Station: An Overview Board of Directors and Its Responsibilities 3 Fundraise Before You Go on the Air! Developing a Budget Creating Your Station Departments General Manager Progr ammin g D epartment Operations Department Development D epartment Business Department On-Air Staff and Volunteers I Volunteerism The FCC: The 3OOPound Gorilla 11 What is a Construction Permit? Are you MX with other Applications? Timing False Claiming of Points The Process LPFM Universal Settlements Equipment Selection 15 Program Department 16 LPFM Broadcast Requirements Station Music Licensing Obligations Operations Department 19 LPFM Rules & Regulations Station Self-Inspection Public Files Operating Logs Call Letters Program Logs License Renewal Emergency Alert System (EAS) Development Department 24 Press Releases Advertising the Station Funding Sources for Your LPFM Station Are You Ready to Write a Grant Proposal? Common Grant Applications Fundraising Avenues Arts and Humanities Councils Employee Giving Programs United Way Opportunities for Radio On-Air Fund Drives Underwriting Event Planning Station Products Business Department 30 Accounts Receivable Accounts Payable Check Requests Separation of Accounting Duties Other Responsibilities NFCB and the Importance of LPFM 33 Sample Table of Contents 34 What is Community Radio? V Community radio broadcasts from a local community perspective on issues in and around the community it serves along with national and international information pertinent to its community. -

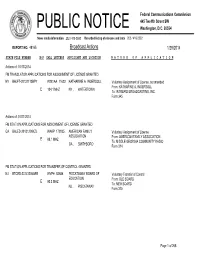

Broadcast Actions 1/29/2014

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48165 Broadcast Actions 1/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 01/13/2014 FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED NY BALFT-20131113BPY W281AA 11623 KATHARINE A. INGERSOLL Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended From: KATHARINE A. INGERSOLL E 104.1 MHZ NY ,WATERTOWN To: INTREPID BROADCASTING, INC. Form 345 Actions of: 01/21/2014 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED GA BALED-20131209XZL WAKP 172935 AMERICAN FAMILY Voluntary Assignment of License ASSOCIATION From: AMERICAN FAMILY ASSOCIATION E 89.1 MHZ To: MIDDLE GEORGIA COMMUNITY RADIO GA ,SMITHBORO Form 314 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR TRANSFER OF CONTROL GRANTED NJ BTCED-20131206AEB WVPH 52686 PISCATAWAY BOARD OF Voluntary Transfer of Control EDUCATION From: OLD BOARD E 90.3 MHZ To: NEW BOARD NJ ,PISCATAWAY Form 315 Page 1 of 268 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 48165 Broadcast Actions 1/29/2014 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 01/22/2014 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR TRANSFER OF CONTROL GRANTED NE BTC-20140103AFZ KSID 35602 KSID RADIO, INC. -

RADIO HOME: GIVING a VOICE to the HOMELESS in SPOKANE, AW SHINGTON Aaron R

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works Spring 2017 RADIO HOME: GIVING A VOICE TO THE HOMELESS IN SPOKANE, AW SHINGTON Aaron R. Bocook Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.ewu.edu/theses Part of the Other Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Bocook, Aaron R., "RADIO HOME: GIVING A VOICE TO THE HOMELESS IN SPOKANE, WASHINGTON" (2017). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 447. http://dc.ewu.edu/theses/447 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADIO HOME: GIVING A VOICE TO THE HOMELESS IN SPOKANE, WASHINGTON A Thesis Presented To Eastern Washington University Cheney, Washington In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts in Critical GIS and Public Anthropology By Aaron R. Bocook Spring 2017 ii THESIS OF AARON R. BOCOOK APPROVED BY ________________________________________ DATE_______ DR. ROBERT SAUDERS, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE ________________________________________ DATE_______ DR. MATTHEW ANDERSON, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE ________________________________________ DATE_______ DR. WILLIAM STIMSON, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE iii ACKNOWLEDEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the professors in the EWU Department of Geography and Anthropology. I will be forever grateful for this opportunity. I owe my deepest gratitude to the men and women who volunteered to share their experiences with me. Reflection can be painful, and the truths I encountered during this process will stay with me. -

Complete Report

Acknowledgments FMC would like to thank Jim McGuinn for his original guidance on playlist data, Joe Wallace at Mediaguide for his speedy responses and support of the project, Courtney Bennett for coding thousands of labels and David Govea for data management, Gabriel Rossman, Peter DiCola, Peter Gordon and Rich Bengloff for their editing, feedback and advice, and Justin Jouvenal and Adam Marcus for their prior work on this issue. The research and analysis contained in this report was made possible through support from the New York State Music Fund, established by the New York State Attorney General at Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, the Necessary Knowledge for a Democratic Public Sphere at the Social Science Research Council (SSRC). The views expressed are the sole responsibility of its author and the Future of Music Coalition. © 2009 Future of Music Coalition Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 4 Programming and Access, Post-Telecom Act ........................................................ 5 Why Payola? ........................................................................................................... 9 Payola as a Policy Problem................................................................................... 10 Policy Decisions Lead to Research Questions...................................................... 12 Research Results .................................................................................................. -

Community Radio, Public Interest: the Low Power Fm Service and 21St Century Media Policy Margo L

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2009 Community Radio, Public Interest: The Low Power Fm Service and 21st Century Media Policy Margo L. Robb University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons Robb, Margo L., "Community Radio, Public Interest: The Low Power Fm Service and 21st Century Media Policy" (2009). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 315. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/315 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMUNITY RADIO, PUBLIC INTEREST: THE LOW POWER FM SERVICE AND 21 st CENTURY MEDIA POLICY A Thesis Presented by MARGO L. ROBB Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 2009 Department of Communication COMMUNITY RADIO, PUBLIC INTEREST: THE LOW POWER FM SERVICE AND 21 st CENTURY MEDIA POLICY A Thesis Presented by MARGO L. ROBB Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________________ Mari Castañeda, Chair ____________________________________________ Sut Jhally, Member __________________________________________ Douglas L. Anderton, Acting Department Head Department of Communication DEDICATION To my amazing family: James Carrott, my husband Amelia and Beatrix, my daughters and Bruce and Janet Robb, my parents L. Bob Rife laughs. “Y’know, watching government regulation trying to keep up with the world is my favorite sport. -

List of Radio Stations in Idaho

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Idaho From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of FCC-licensed radio stations in the U.S. state of Idaho, which can be sorted Contents by their call signs, frequencies, cities of license, licensees, and programming formats. Featured content Current events Call City of license Frequency Licensee [1][2] Format[citation needed] Random article sign [1][2] Donate to Wikipedia KACH 1340 AM Preston Preston Broadcasting, LLC Adult contemporary Wikipedia store KAGF- 105.5 FM Twin Falls Amazing Grace Fellowship Religious Interaction LP Help Christian About Wikipedia KAIO 90.5 FM Idaho Falls Educational Media Foundation Community portal Contemporary (Air1) Recent changes KANP 91.3 FM Ashton Hi-Line Radio Fellowship Inc. Christian Contact page KAOX 107.9 FM Shelley Frandsen Media Company, LLC Top 40 Tools KART 1400 AM Jerome KART Broadcasting Co., Inc. Classic country What links here Pacific Empire Radio Hot adult Related changes KATW 101.5 FM Lewiston Corporation contemporary Upload file Special pages Idaho Conference of Seventh- KAVY 89.1 FM McCall open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com KAVY 89.1 FM McCall Permanent link Day Adventists, Inc. Page information Peak Broadcasting of Boise Wikidata item KAWO 104.3 FM Boise Country Cite this page Licenses, LLC Calvary Chapel of Twin Falls, Religious (CSN Print/export KAWS 89.1 FM Marsing/Murphy Inc. International) Create a book Religious (CSN Download as PDF KAWZ 89.9 FM Twin Falls Calvary Chapel of Twin Falls Printable version International) KAXY- Boundary County Community Languages 98.3 FM Bonners Ferry Variety LP Television Add links KBAR 1230 AM Burley Lee Family Broadcasting, Inc. -

1. About Us 2. Our Reach Market Share Graph Issue Graph 3

page 16 since 1999 2012 Map of Washington Media Outlet Pickup* *A full list of outlets that picked up WNS can be found in section 8. “In the current news landscape, PNS plays a critical role in bringing public- interest stories into communities around the country. We appreciate working with this growing network.” - Roye Anastasio-Bourke, Senior Communications Manager, Annie E. Casey Foundation 1. About Us 2. Our Reach Market Share Graph Issue Graph 3. Why Solution-Focused Journalism Matters (More Than Ever) 4. Spanish News and Talk Show Bookings 5. Member Benefits 6. List of Issues 7. PR Needs (SBS) 8. Media Outlet List Washington News Service • washingtonnewsservice.org page 2 1. About Us What is the Washington News Service? Launched in 1999, the Washington News Service is part of a network of independent public interest state-based news services pioneered by Public News Service. Our mission is an informed and engaged citizenry making educated decisions in service to democracy; and our role is to inform, inspire, excite and sometimes reassure people in a constantly changing environment through reporting spans political, geographic and technical divides. Especially valuable in this turbulent climate for journalism, currently 128 news outlets in Washington and neighboring markets regularly pick up and redistribute our stories. Last year, an average of 33 media outlets used each Washington News Service story. These include outlets like the KAQQ-AM Clear Channel News talk Spokane, KHHO-AM Clear Channel News talk Seattle, KCDA-FM Clear Channel News talk Spokane, KUBE-FM Clear Channel News talk Seattle, KMNT-FM Clear Channel Centralia, National Native News - WA Affiliates, Metro Networks Seattle and Davenport Times. -

FM ATLAS and Station Directory

TWELFTH EDITION i FM ATLAS and Station Directory By Bruce F. Elving A handy Reference to the FM Stations of the United States, Canada and Mexico -C... }( n:J.'Yi'f{)L'i^v0.4_>":.::\ :Y){F.QROv.. ;p;.Qri{.<iÇ.. :.~f., www.americanradiohistory.com i www.americanradiohistory.com FM ATLAS AND STATION DIRECTORY TWELFTH EDITION By Bruce F. Elving, Ph.D CONTENTS: F Musings 2 Key to Symbols 8 FMaps (FM Atlas) 9 Station Directory, Part I (FM Stations by geography) 101 FM Translators [and Boosters] 132 Station Directory, Part II (by frequency) 143 FMemoranda 190 FM Program Formats and Notify Coupon 192 Copyright © Bruce F. Elving, 1989 International Standard Book Number: 0-917170-08-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 89-083679 FM Atlas Publishing Box 336 Esko MN 55733-0336, U. S. A. Historic Address: Adolph MN 55701-0024, U. S. A. www.americanradiohistory.com FMusings Monophonic Translators Via Satellite Threaten Local FM Broadcasting With the Federal Communications Commmission in 1988 allowing noncommer- cial FM translators to get their programs via translators or microwave, the way has been cleared for the big players in religious broadcasting to set up mini -stations all over the country. Hundreds of applications have been filed by Family Stations, Inc. (primary KEAR *106.9 San Francisco), Moody Bible Institute (primary WMBI-FM *90.1 Chicago), and Bible Broadcasting Network (primary WYFG *91.1 Gaffney SC). Cities where such translators would be located are as diverse as Roswell NM, Paris TX, Marquette MI, Pueblo CO and Lincoln NE. As of this book's deadline, only one satellite -delivered translator has been granted in the lower 48 states-in Schroon Lake NY, to Bible Broadcasting Network. -

Thin Air Community Radio 35 W Main, Suite 340 Spokane, WA 99201

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 October 25, 2006 DA 06-2106 In Reply Refer To: Ref. No. 1800B3-PHD/GL Released: October 25, 2006 Mr. John Snyder Thin Air Community Radio 35 W Main, Suite 340 Spokane, WA 99201 Re: Thin Air Community Radio KYRS-LP, Spokane, WA Facility ID No. 135324 File No. BMPL-20060809ALB Application for Minor Modification of Construction Permit Dear Mr. Snyder: This letter refers to the above-captioned application (the “Application”) of Thin Air Community Radio (“Thin Air”) to modify the licensed facilities of KYRS-LP, Spokane, WA. Thin Air proposes to change operations from Channel 237 to Channel 210 at its licensed site. Background. The proposed facility is short-spaced to second-adjacent channel Station KEWU-FM, Cheney, WA, licensed to Eastern Washington University (“EWU”), in violation of Section 73.807 of the Commission’s Rules.1 Thin Air recognizes this violation and requests waiver of the minimum distance separation provisions of Section 73.807. The waiver is requested so KYRS can modify its facilities prior to commencement of program test operations by co-channel Station KPND(FM), Sandpoint, ID. In support of the waiver request, KYRS submits an engineering study based on the relative signal strengths of KYRS and KPND(FM). This so-called “ratio methodology” is used to predict FM translator station interference.2 According to Thin Air, the area of predicted interference would not reach any populated areas. Specifically, the 130.5 dBu interfering contour extends only 22 meters from the KYRS transmission facility. Thin Air and EWU have entered into an agreement (the “EWU Agreement”) under which KEWU has agreed not to object to the grant of the Application provided that Thin Air adheres to certain conditions.