ACCEPTANCE This Dissertation, THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Finale Des Délégations Final List of Delegations Lista Final De Delegaciones

Supplément au Compte rendu provisoire (11 juin 2014) LISTE FINALE DES DÉLÉGATIONS Conférence internationale du Travail 103e session, Genève Supplement to the Provisional Record (11 June2014) FINAL LIST OF DELEGATIONS International Labour Conference 103nd Session, Geneva Suplemento de Actas Provisionales (11 de junio de 2014) LISTA FINAL DE DELEGACIONES Conferencia Internacional del Trabajo 103.a reunión, Ginebra 2014 Workers' Delegate Afghanistan Afganistán SHABRANG, Mohammad Dauod, Mr, Fisrt Deputy, National Employer Union. Minister attending the Conference AFZALI, Amena, Mrs, Minister of Labour, Social Affairs, Martyrs and Disabled (MoLSAMD). Afrique du Sud South Africa Persons accompanying the Minister Sudáfrica ZAHIDI, Abdul Qayoum, Mr, Director, Administration, MoLSAMD. Minister attending the Conference TARZI, Nanguyalai, Mr, Ambassador, Permanent OLIPHANT, Mildred Nelisiwe, Mrs, Minister of Labour. Representative, Permanent Mission, Geneva. Persons accompanying the Minister Government Delegates OLIPHANT, Matthew, Mr, Ministry of Labour. HAMRAH, Hessamuddin, Mr, Deputy Minister, HERBERT, Mkhize, Mr, Advisor to the Minister, Ministry MoLSAMD. of Labour. NIRU, Khair Mohammad, Mr, Director-General, SALUSALU, Pamella, Ms, Private Secretary, Ministry of Manpower and Labour Arrangement, MoLSAMD. Labour. PELA, Mokgadi, Mr, Director Communications, Ministry Advisers and substitute delegates of Labour. OMAR, Azizullah, Mr, Counsellor, Permanent Mission, MINTY, Abdul Samad, Mr, Ambassador, Permanent Geneva. Representative, Permanent Mission, -

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

Africathlète Août 2004

Partenaires Officiels de la CAA Official AAC Partners 2 • africathlete - août 2004 Sommaire Contents Edito Citius, altius, fortius Jeux olympiques d’Athènes 2004 Que brillent les “ Etoiles “ d’Afrique ! Athens 2004 : Let african’s stars shine at athens olympic games ! 14e Championnat d’Afrique à Brazzaville L’Afrique du Sud en force, les performances au rendez-vous 14th African Championship in Brazzaville Performances galore as Shouth Africans rule the roost 15e championnat d’Afrique Rendez-vous à Maurice en 2006 African senior championships See you in Mauririus 2006 Circuit Africain des meetings Un véritable coup d’éclat African meet circuit : Is a remarkable feat Championnats du monde Juniors Les promesses de la jeune sève World junio championships : Africa’s promising young talents La confejes et la CAA à l’air du temp Confejes and CAA keep up with progress août 2004 - africathlete • 3 Editorial Citius, altius, fortius ’Afrique qui gagne, c’est bel et bien l’athlétisme. Vainqueur des quatre dernières éditions de la L Par/by Hamad Kalkaba Malboum Coupe du monde des Confédérations, l’Afrique peut Président de la CAA / AAC President aussi exhiber avec fierté ses multiples champions du monde, détenteurs de records du monde et cham- pions olympiques. Aucune discipline sportive, sur le continent, ne peut encore étaler un pareil palmarès. Et Citius, altius, fortius cerise sur le gâteau, les deux meilleurs athlètes du monde en 2003, en l’occurrence la Sud-Africaine frica is winning through athletics. In addition to win- Hestrie Cloete et le Marocain Hicham El Guerrouj, Aning the last four editions of the Confederations sont des fils de l’Afrique. -

2011 Ucla Men's Track & Field

2011 MEN’S TRACK & FIELD SCHEDULE IINDOORNDOOR SSEASONEASON Date Meet Location January 28-29 at UW Invitational Seattle, WA February 4-5 at New Balance Collegiate Invitational New York, NY at New Mexico Classic Albuquerque, NM February 11-12 at Husky Classic Seattle, WA February 25-26 at MPSF Indoor Championships Seattle, WA March 5 at UW Final Qualifi er Seattle, WA March 11-12 at NCAA Indoor Championships College Station, TX OOUTDOORUTDOOR SSEASONEASON Date Meet Location March 11-12 at Northridge Invitational Northridge, CA March 18-19 at Aztec Invitational San Diego, CA March 25 vs. Texas & Arkansas Austin, TX April 2 vs. Tennessee ** Drake Stadium April 7-9 Rafer Johnson/Jackie Joyner Kersee Invitational ** Drake Stadium April 14 at Mt. SAC Relays Walnut, CA April 17 vs. Oregon ** Drake Stadium April 22-23 at Triton Invitational La Jolla, CA May 1 at USC Los Angeles, CA May 6-7 at Pac-10 Multi-Event Championships Tucson, AZ May 7 at Oxy Invitational Eagle Rock, CA May 13-14 at Pac-10 Championships Tucson, AZ May 26-27 at NCAA Preliminary Round Eugene, OR June 8-11 at NCAA Outdoor Championships Des Moines, IA ** denotes UCLA home meet TABLE OF CONTENTS/QUICK FACTS QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location .............................................................................J.D. Morgan Center, GENERAL INFORMATION ..........................................325 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA, 90095 2011 Schedule .........................Inside Front Cover Athletics Phone ......................................................................(310) -

All Time Men's World Ranking Leader

All Time Men’s World Ranking Leader EVER WONDER WHO the overall best performers have been in our authoritative World Rankings for men, which began with the 1947 season? Stats Editor Jim Rorick has pulled together all kinds of numbers for you, scoring the annual Top 10s on a 10-9-8-7-6-5-4-3-2-1 basis. First, in a by-event compilation, you’ll find the leaders in the categories of Most Points, Most Rankings, Most No. 1s and The Top U.S. Scorers (in the World Rankings, not the U.S. Rankings). Following that are the stats on an all-events basis. All the data is as of the end of the 2019 season, including a significant number of recastings based on the many retests that were carried out on old samples and resulted in doping positives. (as of April 13, 2020) Event-By-Event Tabulations 100 METERS Most Points 1. Carl Lewis 123; 2. Asafa Powell 98; 3. Linford Christie 93; 4. Justin Gatlin 90; 5. Usain Bolt 85; 6. Maurice Greene 69; 7. Dennis Mitchell 65; 8. Frank Fredericks 61; 9. Calvin Smith 58; 10. Valeriy Borzov 57. Most Rankings 1. Lewis 16; 2. Powell 13; 3. Christie 12; 4. tie, Fredericks, Gatlin, Mitchell & Smith 10. Consecutive—Lewis 15. Most No. 1s 1. Lewis 6; 2. tie, Bolt & Greene 5; 4. Gatlin 4; 5. tie, Bob Hayes & Bobby Morrow 3. Consecutive—Greene & Lewis 5. 200 METERS Most Points 1. Frank Fredericks 105; 2. Usain Bolt 103; 3. Pietro Mennea 87; 4. Michael Johnson 81; 5. -

Terrorism in Africa Extremist Groups Threaten Security Across the Continent

New Strategies Turn the Tide Against Terror PLUS A Conversation With Lt. Gen. Robert Kibochi of Kenya IGAD Opens Center to Counter Extremism Reclaiming the Digital Terrain VISIT US ONLINE: ADF-MAGAZINE.COM VOLUME 12 | QUARTER 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS features 8 By the Numbers: Terrorism in Africa Extremist groups threaten security across the continent. 14 Reclaiming the Digital Terrain Radical groups have flourished online. They can’t be silenced, but they can be defeated. 20 ‘Sharpening Our Arrowhead’ Kenya’s vice chief of Defence Forces looks to finish the mission in Somalia and secure the homeland. 28 The Threat at Home ISIS fighters leaving Iraq and Syria may not pose primary threat to Africa. 34 Extremism Roils Northern Mozambique Mystery surrounds an insurgency’s leadership and ideology as violence persists. 40 Center Rallies East Africa Against Extremists An Intergovernmental Authority on Development facility will use research and engagement to counter violent extremism. 44 Protectors or Outlaws? The CJTF of Nigeria shows the benefits and challenges of working with civilian security actors. 50 Group Refutes ISIS Beliefs An anti-extremist organization says the ISIS “handbook” is based on distortions 44 of the Quran. departments 4 Viewpoint 5 African Perspective 26 6 Africa Today 26 African Heartbeat 56 Culture & Sports 58 World Outlook 60 Defense & Security 62 Paths of Hope 64 Growth & Progress 66 Flashback 67 Where Am I? Africa Defense Forum is available online. Please visit us at: adf-magazine.com ON THE COVER: This illustration shows the tools used by extremist groups for violence, recruitment and indoctrination. It illustrates the challenge of fighting terrorism while highlighting the new strategies needed to defeat it. -

89Th NIKE Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Univ.Of Texas-Mike A. Myers Stadium-Austin,TX - 3/30/2016 to 4/2/2016 Results Girls 100 Meter Dash HS Div

Alpha Timing - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 4/4/2016 Page 1 89th NIKE Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Univ.of Texas-Mike A. Myers Stadium-Austin,TX - 3/30/2016 to 4/2/2016 Results Girls 100 Meter Dash HS Div. I ================================================================================= National HS: & 10.98 2015 Candace Hill, Conyers,GA Myers Std: S 11.16 2008 Victoria Jordan, Ft.Worth Dunbar TX Relays: M 11.81 2003 Monique Lee, Navasota Name Year School Seed Prelims Wind H# ================================================================================= Preliminaries 1 Sha'Carri Richardson 10 Dal Carter 11.94 11.74q 2.4 3 2 Kelcie Simmons 10 Leonard 11.22 11.77q 2.4 3 3 Takyera Roberson 12 Hou Wheatley 12.31 11.85q 3.0 4 4 Daja Gordon 11 Dal Hampton Prep 11.72 11.92q 3.0 4 5 Alexis Brown 09 Kennedale 11.96 12.11q 3.0 4 6 Virginia Kerley 11 Taylor 11.26 12.12q 2.6 1 7 Syaira Richardson 11 Nansemond River 12.14 12.15q 3.0 4 8 Jaevin Reed 12 Prestonwood 12.09 12.24q 1.8 2 9 Jernaya Sharp 12 Greenhill School 11.81 12.31q 1.8 2 10 Caira Pettway 11 Sunnyvale 11.66 12.34 1.8 2 12.331 11 Marlee Serrano 11 Sinton 11.75 12.34 3.0 4 12.336 12 Sierra Pruitt 12 Edna 12.31 12.35 3.0 4 13 Taylor Shaw 11 Brusly 11.97 12.37 3.0 4 14 Alexzandra McFarland 11 Georgetown Gateway 11.94 12.38 1.8 2 15 Kennedy Gamble 10 Kinkaid School 11.98 12.41 1.8 2 16 Alex Madlock 11 Bangs 11.93 12.46 2.6 1 17 Tiffani Briggs 12 Cypress Christian 12.51 12.47 3.0 4 18 Ta'la Spates 09 Brusly 12.22 12.50 2.4 3 19 Kierrah Hurd 12 Columbus 12.10 12.52 3.0 4 20 Taylor Roberson 11 Bay City 11.94 12.54 2.4 3 21 Kyla Jimmar 12 Richards (Oak Lawn) 12.50 12.55 1.8 2 12.541 22 Maddie Willet 11 Liberty Chr 12.08 12.55 2.6 1 12.543 23 Jazmin Puryear 11 Lake Worth 12.48 12.60 2.6 1 24 Shannon Stokes 12 Incarn Word Hou 12.30 12.63 1.8 2 25 Tyrisha Hightower 11 Coldspring-Oakhurst 12.43 12.65 1.8 2 26 Justice Coutee-McCullum 09 Hockaday School 12.15 12.68 1.8 2 27 Doneasha Brewer 11 Cin. -

List of Delegations to the Seventieth Session of the General Assembly

UNITED NATIONS ST /SG/SER.C/L.624 _____________________________________________________________________________ Secretariat Distr.: Limited 18 December 2015 PROTOCOL AND LIAISON SERVICE LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE SEVENTIETH SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY I. MEMBER STATES Page Page Afghanistan......................................................................... 5 Chile ................................................................................. 47 Albania ............................................................................... 6 China ................................................................................ 49 Algeria ................................................................................ 7 Colombia .......................................................................... 50 Andorra ............................................................................... 8 Comoros ........................................................................... 51 Angola ................................................................................ 9 Congo ............................................................................... 52 Antigua and Barbuda ........................................................ 11 Costa Rica ........................................................................ 53 Argentina .......................................................................... 12 Côte d’Ivoire .................................................................... 54 Armenia ........................................................................... -

Florence Griffith-Joyner Was a Two-Time Olympian, Earn- Ing Five Medals in the Process

HISTORY/TRADITION HEAD COACHING HISTORY Since 1919, the UCLA men’s track team has been successfully led by six men - Harry Trotter, Elvin C. “Ducky” Drake, Jim Bush, Bob Larsen, Art Venegas and now, Mike Maynard. Behind these men, the Bruins have won eight National Championships, ranging from 1956 to 1988. Harry “Cap” Trotter - 1919 to 1946 Trotter started coaching the track team in 1919, the year UCLA was founded, and was called upon to coach the football team from 1920-1922. During his tenure as head track coach, Trotter produced numerous prominent track and field athletes. The pride of his coaching career were sprinter Jimmy LuValle and his successor, Elvin “Ducky” Drake. Elvin C. “Ducky” Drake - 1946 to 1964 In 19 seasons under Elvin “Ducky” Drake, UCLA had a dual meet record of 107-48-0 (.690) and won one NCAA Championship and one Pac-10 title. Drake was a charter member into the UCLA Hall of Fame in 1984 and was inducted inducted into the USA Track & Field Track & Field Hall of Fame in December of 2007. In 1973, the Bruin track and field complex was officially named “Drake Stadium” in honor of the UCLA coaching legend who had been associated with UCLA as a student-athlete, coach and athletic trainer for over 60 years. Some of Drake’s star athletes include Rafer Johnson, C.K. Yang, George Stanich, Craig Dixon and George Brown. Jim Bush - 1965 to 1984 Bush had incredible success during his 20 years as head coach, as UCLA won five NCAA Championships, seven Conference Championships and seven national dual meet titles under his guidance. -

Copyright by Daniel Lukas Rosenke 2020 the Dissertation Committee for Daniel Lukas Rosenke Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Daniel Lukas Rosenke 2020 The Dissertation Committee for Daniel Lukas Rosenke Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Supply and Enhance: Tracing the Doping Supply Chain in the 1980s Committee: Janice S. Todd, Supervisor Thomas M. Hunt Tolga Ozyurtcu John Hoberman Ian Ritchie Supply and Enhance: Tracing the Doping Supply Chain in the 1980s by Daniel Lukas Rosenke Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2020 Dedication To my mother, the strongest woman I know To Adam: my brother, best friend, and forever my partner in crime Acknowledgements This project may never have come to fruition without the influence of father, Scott Rosenke. In my young and more impressionable years, he molded me into a man of confidence and conviction, and inspired in me the unwavering self-belief to pursue my dreams, no matter how far-fetched. Perhaps most significantly, I credit him with first introducing me to the subject matter I discuss in this volume, and piquing my interest in the surreptitious drug culture in Olympic and professional sports. Sometime in our mid-teens, I recall my brother Adam – my handsome identical twin – and I seated on the couch with Dad watching Lance Armstrong’s second Tour de France victory. At the time many believed the brash cycling maverick from Plano, Texas, a folk hero among cancer survivors worldwide, was a manna from heaven, sent to restore faith in the sport after a widely-reported scandal at the Tour two years earlier. -

2020 21 Media Guide Comple

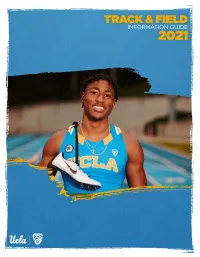

2021 UCLA TRACK & FIELD 2021 QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location Los Angeles, CA The 2021 Bruins Men’s All-Time Indoor Top 10 65-66 Rosters 2-3 Athletic Dept. Address 325 Westwood Plaza Women’s All-Time Indoor Top 10 67-68 Coaching Staff 4-9 Los Angeles, CA 90095 Men’s All-Time Outdoor Top 10 69-71 Men’s Athlete Profles 10-26 Athletics Phone (310) 825-8699 Women’s All-Time Outdoor Top 10 72-74 Women’s Athlete Profles 27-51 Ticket Offce (310) UCLA-WIN Drake Stadium 75 Track & Field Offce Phone (310) 794-6443 History/Records Drake Stadium Records 76 Chancellor Dr. Gene Block UCLA-USC Dual Meet History 52 Bruins in the Olympics 77-78 Director of Athletics Martin Jarmond Pac-12 Conference History 53-55 USA Track & Field Hall of Fame Bruins 79-81 Associate Athletic Director Gavin Crew NCAA Championships All-Time Results 56 Sr. Women’s Administrator Dr. Christina Rivera NCAA Men’s Champions 57 Faculty Athletic Rep. Dr. Michael Teitell NCAA Women’s Champions 58 Home Track (Capacity) Drake Stadium (11,700) Men’s NCAA Championship History 59-61 Enrollment 44,742 Women’s NCAA Championship History 62-63 NCAA Indoor All-Americans 64 Founded 1919 Colors Blue and Gold Nickname Bruins Conference Pac-12 National Affliation NCAA Division I Director of Track & Field/XC Avery Anderson Record at UCLA (Years) Fourth Year Asst. Coach (Jumps, Hurdles, Pole Vault) Marshall Ackley Asst. Coach (Sprints, Relays) Curtis Allen Asst. Coach (Distance) Devin Elizondo Asst. Coach (Distance) Austin O’Neil Asst. -

Doha 2018: Compact Athletes' Bios (PDF)

Men's 200m Diamond Discipline 04.05.2018 Start list 200m Time: 20:36 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Rasheed DWYER JAM 19.19 19.80 20.34 WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 20.08.09 2 Omar MCLEOD JAM 19.19 20.49 20.49 AR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 NR 19.97 Femi OGUNODE QAT Bruxelles 11.09.15 3 Nethaneel MITCHELL-BLAKE GBR 19.94 19.95 WJR 19.93 Usain BOLT JAM Hamilton 11.04.04 4 Andre DE GRASSE CAN 19.80 19.80 MR 19.85 Ameer WEBB USA 06.05.16 5 Ramil GULIYEV TUR 19.88 19.88 DLR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM Bruxelles 16.09.11 6 Jereem RICHARDS TTO 19.77 19.97 20.12 SB 19.69 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria 16.03.18 7 Noah LYLES USA 19.32 19.90 8 Aaron BROWN CAN 19.80 20.00 20.18 2018 World Outdoor list 19.69 -0.5 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria 16.03.18 19.75 +0.3 Steven GARDINER BAH Coral Gables, FL 07.04.18 Medal Winners Doha previous Winners 20.00 +1.9 Ncincihli TITI RSA Columbia 21.04.18 20.01 +1.9 Luxolo ADAMS RSA Paarl 22.03.18 16 Ameer WEBB (USA) 19.85 2017 - London IAAF World Ch. in 20.06 -1.4 Michael NORMAN USA Tempe, AZ 07.04.18 14 Nickel ASHMEADE (JAM) 20.13 Athletics 20.07 +1.9 Anaso JOBODWANA RSA Paarl 22.03.18 12 Walter DIX (USA) 20.02 20.10 +1.0 Isaac MAKWALA BOT Gaborone 29.04.18 1.