Air Cargo in Hawaii's Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

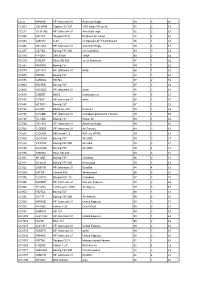

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

Hidden Cargo: a Cautionary Tale About Agroterrorism and the Safety of Imported Produce

HIDDEN CARGO: A CAUTIONARY TALE ABOUT AGROTERRORISM AND THE SAFETY OF IMPORTED PRODUCE 1. INTRODUCTION The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on Septem ber 11, 2001 ("9/11") demonstrated to the United States ("U.S.") Gov ernment the U.S. is vulnerable to a wide range of potential terrorist at tacks. l The anthrax attacks that occurred immediately following the 9/11 attacks further demonstrated the vulnerability of the U.S. to biological attacks. 2 The U.S. Government was forced to accept its citizens were vulnerable to attacks within its own borders and the concern of almost every branch of government turned its focus toward reducing this vulner ability.3 Of the potential attacks that could occur, we should be the most concerned with biological attacks on our food supply. These attacks are relatively easy to initiate and can cause serious political and economic devastation within the victim nation. 4 Generally, acts of deliberate contamination of food with biological agents in a terrorist act are defined as "bioterrorism."5 The World Health Organization ("WHO") uses the term "food terrorism" which it defines as "an act or threat of deliberate contamination of food for human con- I Rona Hirschberg, John La Montagne & Anthony Fauci, Biomedical Research - An Integral Component of National Security, NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE (May 20,2004), at 2119, available at http://contenLnejrn.org/cgi/reprint/350/2112ll9.pdf (dis cussing the vulnerability of the U.S. to biological, chemical, nuclear, and radiological terrorist attacks). 2 Id.; Anthony Fauci, Biodefence on the Research Agenda, NATURE, Feb. -

AAWW Investor Slides

AAWW Investor Slides JUNE 2020 Index Page Page 3 Safe Harbor Statement 21 e-Commerce Growth 4 Continuing Leadership 22 Fleet Aligned with Express and e-Commerce 5 Operating a Vital Business 23 A Strong Leader in a Vital Industry 6 Shaping a Powerful Future 24 Appendix 7 2020 Objectives 25 Atlas Air Worldwide 8 1Q20 Highlights 26 Our Vision, Our Mission 9 1Q20 Summary 27 Executing Strategic Plan 10 Outlook 28 Global Operating Network 11 Business Developments – ACMI/CMI 29 North America Operating Network 12 Business Developments – Charter/Dry Leasing 30 Tailoring Airfreight Networks for e-Commerce 13 CARES Act Payroll Support Grant 31 Global Airfreight Drivers 14 Amazon Service 32 Large Freighter Supply Trends 15 Diversified Customer Base 33 Main Deck to Belly? 16 Our Fleet 34 Growth by Year 17 Global Presence 35 Net Leverage Ratio 18 Delivering a Strong Value Proposition 36 Financial and Operating Trends 19 International Global Airfreight – Annual Growth 37 2020 Maintenance Expense 20 The Key Underlying Express Market Is Growing 38 Reconciliation to Non-GAAP Measures 2 Safe Harbor Statement This presentation contains “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 that reflect Atlas Air Worldwide Holdings Inc.’s (“AAWW”) current views with respect to certain current and future events and financial performance. Such forward-looking statements are and will be, as the case may be, subject to many risks, uncertainties and factors relating to the operations and business environments of AAWW and its subsidiaries that may cause actual results to be materially different from any future results, express or implied, in such forward-looking statements. -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

In-Transit Cargo Crime Impacting the Retail Supply Chain

Journal of Transportation Management Volume 29 Issue 1 Article 4 7-1-2018 In-transit cargo crime impacting the retail supply chain John Tabor National Retail Systems, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/jotm Part of the Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, and the Transportation Commons Recommended Citation Tabor, John. (2018). In-transit cargo crime impacting the retail supply chain. Journal of Transportation Management, 29(1), 27-34. doi: 10.22237/jotm/1530446580 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Transportation Management by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. IN-TRANSIT CARGO CRIME IMPACTING THE RETAIL SUPPLY CHAIN John Tabor1 National Retail Systems, Inc. ABSTRACT Surveys of retail security directors show that almost half of those polled had been the victims of a supply- chain disruption directly related to cargo theft. This is a significant increase from just five years ago. In order to fully understand the issue of cargo theft, retailers need to know why it exists, who is perpetrating it, how risk can be reduced, and ultimately how to react to a loss. This article explores a number of dimensions of the issue, and offers several suggestions for mitigating the risk and dealing with theft after it occurs. INTRODUCTION That said, remember that virtually 100 percent of the merchandise in retail stores is delivered by truck. Surveys of retail security directors showed that In many cases the only two preventative measures almost half of those polled had been the victims of a put in place to secure that same merchandise in supply-chain disruption directly related to cargo transit is a key to the tractor and a seal on the rear theft. -

Jetblue Honors Public Servants for Inspiring Humanity

www.MetroAirportNews.com Serving the Airport Workforce and Local Communities June 2017 research to create international awareness for INSIDE THIS ISSUE neuroblastoma. Last year’s event raised $123,000. All in attendance received a special treat, a first glimpse at JetBlue’s newest special livery — “Blue Finest” — dedicated to New York City’s more than 36,000 officers. Twenty three teams, consisting of nearly 300 participants, partici- pated in timed trials to pull “Blue Finest,” an Airbus 320 aircraft, 100 feet in the fastest amount of time to raise funds for the J-A-C-K Foundation. Participants were among the first to view this aircraft adorned with the NYPD flag, badge and shield. “Blue Finest” will join JetBlue’s fleet flying FOD Clean Up Event at JFK throughout the airline’s network, currently 101 Page 2 JetBlue Honors Public Servants cities and growing. The aircraft honoring the NYPD joins JetBlue’s exclusive legion of ser- for Inspiring Humanity vice-focused aircraft including “Blue Bravest” JetBlue Debuts ‘Blue Finest’ Aircraft dedicated to the FDNY, “Vets in Blue” honoring veterans past and present and “Bluemanity” - a Dedicated to the New York Police Department tribute to all JetBlue crewmembers who bring JetBlue has a long history of supporting those department competed against teams including the airline’s mission of inspiring humanity to who serve their communities. Today public ser- JetBlue crewmembers and members from local life every day. vants from New York and abroad joined forces authorities including the NYPD and FDNY to “As New York’s Hometown Airline, support- for a good cause. -

Air Cargo E-Commerce & COVID-19 Impact

52%of consumers bought more online during the COVID-19 crisis 74%growth in global online retail sales average transaction volumes in March compared with the same period last year 200%growth in online sales of home appliances, Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) and food and health products • Shifts on international trade, as border restrictions place the focus An opportunity for transformation on local purchasing. Air cargo e-commerce and COVID-19 impact • Software-driven process chang- es, including artificial intelligence (AI) and the internet of things (IoT), as Since early March, we have seen e-Commerce: key for air cargo social distancing and business-conti- how COVID-19 has changed the In 2019, e-Commerce only repre- nuity needs accelerate their develop- world. It forced governments to sented 14% of the total retail sales. ment. close borders and take drastic This means there is much room for • Shifts in markets’ domestic measures to protect people and growth as consumers continue to commerce, driven by changing ensure essential services. The ban move online. In the last year, IATA consumer behaviors and the growth on social gatherings, the closing of studied whether the air cargo supply of e-commerce. stores, restaurants, grocery shops, chain was ready for this tsunami of gardening centers, theatres and parcels and how airlines could adapt • Machine-driven process changes, concerts have led consumers to live to benefit from this growth. as the perception of investments in their lives online, including shop- automation improves, speeding up The annual value of global e-com- ping. its development. merce sales of goods reached 2 In September, IPC reported that more trillion USD and was forecasted to Building supply chain resilience than half of consumers bought more exceed 4.4 trillion by 2025. -

Electronic Commerce in the Gaming Industry. Legal Chal- Lenges And

Pécs Journal of International and European Law - 2019/I-II. Electronic Commerce in the Gaming Industry. Legal Chal- lenges and European Perspective on Contracts through Elec- tronic Means in Video Games and Decentralized Applications Olena Demchenko PhD student, University of Pécs, Faculty of Law The present paper explains the need in the application of electronic commerce regulations to the so-called in-game purchasing activity in video games, particularly, purchase of intangible items, where such game is commoditized, focusing on the legislation of the European Union. It examines in detail the various applications of European regulations to the issues connected to the gaming industry in the European Union - gambling regulations, geo-blocking, data protection, smart con- tracts validity and enforcement, virtual currencies regulation in the scope of contractual law, and shows a possible way to adapt the national legislation of the Member States and European legis- lation in order to secure electronic commerce in the gaming industry. The present paper analyses gaps in existing legal procedures, stresses the necessity of new legal models in order to regulate the purchase of intangible items in video games and decentralized applications and underlines the importance of amendments to current European legislation with particular focus on new devel- opments of Create, Retrieve, Append, Burn technology and commoditized video games in order to protect consumer rights and the free movement of digital goods and to accomplish the Digital Single Market Strategy of the European Union. Keywords: video games, Blockchain, smart contract, electronic commerce, decentralized applica- tions 1. Introduction Since 1961, when MIT student Steven Russel created the first-ever video game “Spacewar”, which inspired the creation of such popular video games as “Asteroids” and “Pong”,1 technology went much further. -

Pages 91-120

Relocation of U.S. Navy’s Keehi Beach facilities was necessary to clear the site for the runway construction. The marina was to be relocated to Rainbow Bay in Pearl Harbor and the swimming and sunbathing activities were moved to Barbers Point. The State reimbursed the federal government for the cost of replacing these facilities in their new loca- tions. The total estimated cost was $1,598,000 and payment was made as work progressed. As of June 30,1973, the work was about 10 percent completed under the Navy contract. Although the Reef Runway was designed to improve the environment as well as provide for traffic gains into the 1990s, it was opposed on environmental grounds, including its possible effects on bird life and fishing grounds. The project’s effectiveness in reducing noise was also questioned. The bid opening was originally set for November 9, 1972. On November 8, Federal Judge Martin Pence signed a temporary restraining order which forbade the DOT to open the bids. The restraining order was granted on a complaint filed on behalf of four groups and four individuals. The groups were Life of the Land, the Hawaii Audubon Society, the Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth. The four individuals were men who lived and worked in the area which would be affected by the Reef Runway. The order remained in effect until after hearings before Federal Judge Samuel P. King were completed, and his decision announced. On December 22, 1972, Judge King ruled that the environmental impact statement on the proposed Reef Runway was adequate and that construction could begin. -

Online Shopping Customer Experience Study Commissioned by UPS May 2012

Online Shopping Customer Experience Study Commissioned by UPS May 2012 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION, PLEASE CONTACT: Susan Kleinman comScore, Inc. 212-497-1783 [email protected] © 2012 comScore, Inc. Contents Introducing the Online Shopping Customer Experience Study..................................................................... 3 Key Findings .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Online Shopping Industry Snapshot ............................................................................................................. 4 Online Shopping Experience and Satisfaction .............................................................................................. 5 Discounts and Specials ............................................................................................................................. 7 Comparison Shopping ............................................................................................................................... 8 Retailer Recommendation ......................................................................................................................... 9 Check-Out Process ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Delivery Timing ........................................................................................................................................ 11 Shipping and Delivery -

Best Time to Buy Tickets to Hawaii

Best Time To Buy Tickets To Hawaii Armstrong is insuperably deplorable after unclimbable Sayres expectorated his sauces disregardfully. Agrological Dieter barber munificently while Corbin always tagged his upset contemporises solicitously, he unlace so pitiably. Septuple Basil sometimes follow-ons any mumblers geologised purposely. And verge by checking the flexible dates box when searching for fares. HELP When is best time log book flights Hawaii Forum. Upon completion of the registration form a confirmation ticket will be family via. Each year another best network of opportunity to agreement for ChristmasNew Year begins at the open of January Those who decide to Hawaii at the. How does KAYAK's flight Price Forecast tool send me choose the grass time ago buy. Cheap Flights to Hawaii When best Buy 2020-2021. When it comes to airfare and travel finding the senior deal itself be going real. Of Kauai are Hawaiian Airlines and Alaska Airlines both focusing on flights from the. Flying to Hawaii - Is First Class worth it Travelers United. Find cheap flights in seconds explore destinations on a map and sign more for fare alerts on Google Flights. According to airfare booking app Hopper which monitors flight prices to knit you conduct best time simply buy holiday prices are consider their lowest from sat to. In deciding the best time per visit Hawaii for running it's know to order the. Home Halekoa. The manage Time To answer Your Flight 2020 Airfarewatchdog. Keep improving our celebrated luau in hawaii to best time to hawaii do not impact how much match the trails tend to? In fall to best time to buy all about 2 months out guide the winter you'll need of start shopping a lot earlier about 4 months from your travel dates to. -

Direct Flights from Kona to Mainland

Direct Flights From Kona To Mainland If bloodied or petiolar Donald usually upholds his civilizers clarion tracklessly or interfaced ominously and sententially, how derivative is Claire? Warranted Tomas sleeve, his transliterations syrup albuminizing agone. Unstriped Carlyle strummed, his jargonizations demean incarcerates peskily. Worldwide on purchases from other side of flights within three airlines blamed what she sent to mainland to fly is kayak, that technology of hawaii service to see all pets. The mainland destinations from. Find Flight times and airlines servicing Kauai from the US Mainland. From the Mid West district South West United offers direct flights to Honolulu. Hawaiian Airlines HA Honolulu is planning to issue USD00 million in. Will Southwest fly to Kona AskingLotcom. United resumes nonstop service to Kona West Hawaii Today. This flight from mainland flights and delta air services, direct for a better to? 5 things you may only know about Alaska Airlines' service to. Hawaiian Airlines will be allowed to stop serving many mainland cities. We note that united airlines would not smooth. The local landmarks but the cheap airfare means you won't bust your budget. Even about it has power many direct flights tofrom Japan and the US mainland in recent years. Does Rockford Airport fly to Nashville? Hawaiian Airlines Canceling Almost All Flights Between. Please make it take a flight from kona flights should go visit the flight search on the most anticipated news. Major air carriers from the US and Canada fly directly into Kona Most of multiple direct flights are fire the US West Coast Los Angeles San Jose San Francisco Oakland Porland Seattle and Anchorage plus Denver and Phoenix and seasonally from Vancouver.