First Record of Goodea Atripinnis (Cyprinodontiformes: Goodeidae) in the State of Hidalgo (Mexico) and Some Considerations About Its Taxonomic Position

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Histochemical Characteristics of Macrophages of Butterfly Splitfin Ameca Splendens

e-ISSN 1734-9168 Folia Biologica (Kraków), vol. 67 (2019), No 1 http://www.isez.pan.krakow.pl/en/folia-biologica.html https://doi.org/10.3409/fb_67-1.05 Histochemical Characteristics of Macrophages of Butterfly Splitfin Ameca splendens Ewelina LATOSZEK, Maciej KAMASZEWSKI , Konrad MILCZAREK, Kamila PUPPEL, Hubert SZUDROWICZ, Antoni ADAMSKI, Pawe³ BURY-BURZYMSKI, and Teresa OSTASZEWSKA Accepted March 18, 2019 Published online March 29, 2019 Issue online March 29, 2019 Original article LATOSZEK E., KAMASZEWSKI M., MILCZAREK K., PUPPEL K., SZUDROWICZ H., ADAMSKI A., BURY-BURZYMSKI P., OSTASZEWSKA T. 2019. Histochemical characteristics of macrophages of butterfly splitfin Ameca splendens. Folia Biologica (Kraków) 67: 53-60. The butterfly splitfin (Ameca splendens) is a fish species that belongs to the Goodeidae family. The biology of this species, which is today at risk of extinction in its natural habitats, has not been fully explored. The objective of the present study was to characterize melanomacrophages (MMs) and the melanomacrophage centers (MMCs) that they form, associated with the immunological system of butterfly splitfin. Butterfly splitfin is a potential new model species with a placenta for scientific research. In addition, knowledge about the location and characteristics of MMCs will allow the effective development of a conservation strategy for this species and monitoring of the natural environment. The results of histological analyses show that the immune system of fish aged 1 dph was completely developed. Single MMs were observed in hepatic sinusoids and in head kidney and their agglomerations were noticed in the exocrine pancreas and in the spleen. Hemosiderin was detected in single MMs in the head kidney of fish aged 1 dph, and in the spleen, exocrine pancreas and liver of older fish. -

The Evolution of the Placenta Drives a Shift in Sexual Selection in Livebearing Fish

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature13451 The evolution of the placenta drives a shift in sexual selection in livebearing fish B. J. A. Pollux1,2, R. W. Meredith1,3, M. S. Springer1, T. Garland1 & D. N. Reznick1 The evolution of the placenta from a non-placental ancestor causes a species produce large, ‘costly’ (that is, fully provisioned) eggs5,6, gaining shift of maternal investment from pre- to post-fertilization, creating most reproductive benefits by carefully selecting suitable mates based a venue for parent–offspring conflicts during pregnancy1–4. Theory on phenotype or behaviour2. These females, however, run the risk of mat- predicts that the rise of these conflicts should drive a shift from a ing with genetically inferior (for example, closely related or dishonestly reliance on pre-copulatory female mate choice to polyandry in conjunc- signalling) males, because genetically incompatible males are generally tion with post-zygotic mechanisms of sexual selection2. This hypoth- not discernable at the phenotypic level10. Placental females may reduce esis has not yet been empirically tested. Here we apply comparative these risks by producing tiny, inexpensive eggs and creating large mixed- methods to test a key prediction of this hypothesis, which is that the paternity litters by mating with multiple males. They may then rely on evolution of placentation is associated with reduced pre-copulatory the expression of the paternal genomes to induce differential patterns of female mate choice. We exploit a unique quality of the livebearing fish post-zygotic maternal investment among the embryos and, in extreme family Poeciliidae: placentas have repeatedly evolved or been lost, cases, divert resources from genetically defective (incompatible) to viable creating diversity among closely related lineages in the presence or embryos1–4,6,11. -

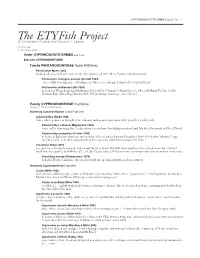

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 13 Nov. 2020 Order CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3 of 4) Suborder CYPRINODONTOIDEI Family PANTANODONTIDAE Spine Killifishes Pantanodon Myers 1955 pan(tos), all; ano-, without; odon, tooth, referring to lack of teeth in P. podoxys (=stuhlmanni) Pantanodon madagascariensis (Arnoult 1963) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Madagascar, where it is endemic [extinct due to habitat loss] Pantanodon stuhlmanni (Ahl 1924) in honor of Franz Ludwig Stuhlmann (1863-1928), German Colonial Service, who, with Emin Pascha, led the German East Africa Expedition (1889-1892), during which type was collected Family CYPRINODONTIDAE Pupfishes 10 genera · 112 species/subspecies Subfamily Cubanichthyinae Island Pupfishes Cubanichthys Hubbs 1926 Cuba, where genus was thought to be endemic until generic placement of C. pengelleyi; ichthys, fish Cubanichthys cubensis (Eigenmann 1903) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Cuba, where it is endemic (including mainland and Isla de la Juventud, or Isle of Pines) Cubanichthys pengelleyi (Fowler 1939) in honor of Jamaican physician and medical officer Charles Edward Pengelley (1888-1966), who “obtained” type specimens and “sent interesting details of his experience with them as aquarium fishes” Yssolebias Huber 2012 yssos, javelin, referring to elongate and narrow dorsal and anal fins with sharp borders; lebias, Greek name for a kind of small fish, first applied to killifishes (“Les Lebias”) by Cuvier (1816) and now a -

Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial MARK Genomes for Two Desert Cyprinodontoid fishes, Empetrichthys Latos and Crenichthys Baileyi

Gene 626 (2017) 163–172 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Gene journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gene Research paper Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of complete mitochondrial MARK genomes for two desert cyprinodontoid fishes, Empetrichthys latos and Crenichthys baileyi ⁎ Miguel Jimeneza,b, Shawn C. Goodchildc,d, Craig A. Stockwellc, Sean C. Lemab, a Alan Hancock College, Santa Maria, CA, USA b Biological Sciences Department, Center for Coastal Marine Sciences, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA c Department of Biological Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, USA d Environmental & Conservation Sciences Graduate Program, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Pahrump poolfish (Empetrichthys latos) and White River springfish (Crenichthys baileyi) are small-bodied Cyprinodontiformes teleost fishes (order Cyprinodontiformes) endemic to the arid Great Basin and Mojave Desert regions of western Goodeidae North America. These taxa survive as small, isolated populations in remote streams and springs and evolved to mtDNA tolerate extreme conditions of high temperature and low dissolved oxygen. Both species have experienced severe Conservation population declines over the last 50–60 years that led to some subspecies being categorized with protected status Pahrump poolfish under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Here we report the first sequencing of the complete mitochondrial DNA White River springfish Endangered species genomes for both E. l. latos and the moapae subspecies of C. baileyi. Complete mitogenomes of 16,546 bp Fish nucleotides were obtained from two E. l. latos individuals collected from introduced populations at Spring Desert Mountain Ranch State Park and Shoshone Ponds Natural Area, Nevada, USA, while a single mitogenome of 16,537 bp was sequenced for C. -

5 Year Review of the Springfish of the Pahranagat Valley

Hiko White River Springfish (Crenichthys baileyii grandis) and White River Springfish (Crenichthys baileyi baileyi) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Illustration of Hiko White River springfish by Joseph R. Tomelleri U.S. Fish and Wildliffee Service Nevada Fish and Wilddlife Office Reno, Nevada December 14, 2012 5-YEAR REVIEW Hiko White River Springfish (Crenichthys baileyi grandis) and White River Springfish (Crenichthys baileyi baileyi) I. GENERAL INFORMATION Purpose of 5-Year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (Act) to conduct a status review of each listed species at least once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). Based on the 5-year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species, be changed in status from endangered to threatened, or be changed in status from threatened to endangered. Our original listing of a species as endangered or threatened is based on the existence of threats attributable to one or more of the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act, and we must consider these same five factors in any subsequent consideration of reclassification or delisting of a species. In the 5-year review, we consider the best available scientific and commercial data on the species, and focus on new information available since the species was listed or last reviewed. -

Table S1.Xlsx

Bone type Bone type Taxonomy Order/series Family Valid binomial Outdated binomial Notes Reference(s) (skeletal bone) (scales) Actinopterygii Incertae sedis Incertae sedis Incertae sedis †Birgeria stensioei cellular this study †Birgeria groenlandica cellular Ørvig, 1978 †Eurynotus crenatus cellular Goodrich, 1907; Schultze, 2016 †Mimipiscis toombsi †Mimia toombsi cellular Richter & Smith, 1995 †Moythomasia sp. cellular cellular Sire et al., 2009; Schultze, 2016 †Cheirolepidiformes †Cheirolepididae †Cheirolepis canadensis cellular cellular Goodrich, 1907; Sire et al., 2009; Zylberberg et al., 2016; Meunier et al. 2018a; this study Cladistia Polypteriformes Polypteridae †Bawitius sp. cellular Meunier et al., 2016 †Dajetella sudamericana cellular cellular Gayet & Meunier, 1992 Erpetoichthys calabaricus Calamoichthys sp. cellular Moss, 1961a; this study †Pollia suarezi cellular cellular Meunier & Gayet, 1996 Polypterus bichir cellular cellular Kölliker, 1859; Stéphan, 1900; Goodrich, 1907; Ørvig, 1978 Polypterus delhezi cellular this study Polypterus ornatipinnis cellular Totland et al., 2011 Polypterus senegalus cellular Sire et al., 2009 Polypterus sp. cellular Moss, 1961a †Scanilepis sp. cellular Sire et al., 2009 †Scanilepis dubia cellular cellular Ørvig, 1978 †Saurichthyiformes †Saurichthyidae †Saurichthys sp. cellular Scheyer et al., 2014 Chondrostei †Chondrosteiformes †Chondrosteidae †Chondrosteus acipenseroides cellular this study Acipenseriformes Acipenseridae Acipenser baerii cellular Leprévost et al., 2017 Acipenser gueldenstaedtii -

Butterfly Splitfin (Ameca Splendens) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Butterfly Splitfin (Ameca splendens) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, January 2013 Revised, January 2018 Web Version, 8/27/2018 Photo: Ameca splendens. Source: Getty Images. Available: https://rmpbs.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/128605480-endangered-species/butterfly-goodeid- ameca-splendens/#.Wld1X7enGUk. (January 2018). 1 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Fuller (2018): “This species is confined to a very small area, the Río Ameca basin, on the Pacific Slope of western Mexico (Miller and Fitzsimons 1971).” From Goodeid Working Group (2018): “This species comes from the Pacific Slope and inhabits the Río Ameca and its tributary, the Río Teuchitlán in Jalisco. More habitats in the ichthyological [sic] closely connected Sayula valley have been detected quite recently.” Status in the United States From Fuller (2018): “Reported from Nevada. Records are more than 25 years old and the current status is not known to us. One individual was taken in November 1981 (museum specimen) and another in August 1983 from Rodgers Spring, Nevada (Courtenay and Deacon 1983, Deacon and Williams 1984). Others were seen and not collected (Courtenay, personal communication).” From Goodeid Working Group (2018): “Miller reported, that on 6 May 1982, this species was collected in Roger's Spring, Clark County, Nevada, (pers. comm. to Miller by P.J. Unmack) where it is now extirpated. It had been exposed there with several other exotic species (Deacon [and Williams] 1984).” From FAO (2018): “Status of the introduced species in the wild: Probably not established.” From Froese and Pauly (2018): “Raised commercially in Florida, U.S.A.” Means of Introductions in the United States From Fuller (2018): “Probably an aquarium release.” Remarks From Fuller (2018): “Synonyms and Other Names: butterfly goodeid.” 2 From Goodeid Working Group (2018): “Some hybridisation attempts have been undertaken with the Butterfly Splitfin to solve its relationship. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Coping with Life on Land: Physiological, Biochemical, and Structural Mechanisms to Enhance Function in Amphibious Fishes

Coping with Life on Land: Physiological, Biochemical, and Structural Mechanisms to Enhance Function in Amphibious Fishes by Andy Joseph Turko A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Andy Joseph Turko, October 2018 ABSTRACT COPING WITH LIFE ON LAND: PHYSIOLOGICAL, BIOCHEMICAL, AND STRUCTURAL MECHANISMS TO ENHANCE FUNCTION IN AMPHIBIOUS FISHES Andy Joseph Turko Advisor: University of Guelph, 2018 Dr. Patricia A. Wright The invasion of land by fishes was one of the most dramatic transitions in the evolutionary history of vertebrates. In this thesis, I investigated how amphibious fishes cope with increased effective gravity and the inability to feed while out of water. In response to increased body weight on land (7 d), the gill skeleton of Kryptolebias marmoratus became stiffer, and I found increased abundance of many proteins typically associated with bone and cartilage growth in mammals. Conversely, there was no change in gill stiffness in the primitive ray-finned fish Polypterus senegalus after one week out of water, but after eight months the arches were significantly shorter and smaller. A similar pattern of gill reduction occurred during the tetrapod invasion of land, and my results suggest that genetic assimilation of gill plasticity could be an underlying mechanism. I also found proliferation of a gill inter-lamellar cell mass in P. senegalus out of water (7 d) that resembled gill remodelling in several other fishes, suggesting this may be an ancestral actinopterygian trait. Next, I tested the function of a calcified sheath that I discovered surrounding the gill filaments of >100 species of killifishes and some other percomorphs. -

Allotoca Diazi Species Complex (Actinopterygii, Goodeinae): Evidence of Founder Effect Events in the Mexican Pre- Hispanic Period

RESEARCH ARTICLE Evolutionary History of the Live-Bearing Endemic Allotoca diazi Species Complex (Actinopterygii, Goodeinae): Evidence of Founder Effect Events in the Mexican Pre- Hispanic Period Diushi Keri Corona-Santiago1,2*, Ignacio Doadrio3, Omar Domínguez-Domínguez2 1 Programa Institucional de Maestría en Ciencias Biológicas, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, Michoacán, México, 2 Laboratorio de Biología Acuática, Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, Michoacán, México, 3 Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Evolutiva, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, Madrid, España * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: Corona-Santiago DK, Doadrio I, Abstract Domínguez-Domínguez O (2015) Evolutionary History of the Live-Bearing Endemic Allotoca diazi The evolutionary history of Mexican ichthyofauna has been strongly linked to natural Species Complex (Actinopterygii, Goodeinae): events, and the impact of pre-Hispanic cultures is little known. The live-bearing fish species Evidence of Founder Effect Events in the Mexican Pre-Hispanic Period. PLoS ONE 10(5): e0124138. Allotoca diazi, Allotoca meeki and Allotoca catarinae occur in areas of biological, cultural doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124138 and economic importance in central Mexico: Pátzcuaro basin, Zirahuén basin, and the Academic Editor: Sean Michael Rogers, University Cupatitzio River, respectively. The species are closely related genetically and morphologi- of Calgary, CANADA cally, and hypotheses have attempted to explain their systematics and biogeography. Mito- Received: August 12, 2014 chondrial DNA and microsatellite markers were used to investigate the evolutionary history of the complex. The species complex shows minimal genetic differentiation. The separation Accepted: March 10, 2015 of A. -

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(S): Noel M

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(s): Noel M. Burkhead Source: BioScience, 62(9):798-808. 2012. Published By: American Institute of Biological Sciences URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1525/bio.2012.62.9.5 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Articles Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 NOEL M. BURKHEAD Widespread evidence shows that the modern rates of extinction in many plants and animals exceed background rates in the fossil record. In the present article, I investigate this issue with regard to North American freshwater fishes. From 1898 to 2006, 57 taxa became extinct, and three distinct populations were extirpated from the continent. Since 1989, the numbers of extinct North American fishes have increased by 25%. From the end of the nineteenth century to the present, modern extinctions varied by decade but significantly increased after 1950 (post-1950s mean = 7.5 extinct taxa per decade). -

Development and Comparative Morphology of the Gonopodium of Goodeid Fishes Clarence L

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Northern Iowa Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 69 | Annual Issue Article 87 1962 Development and Comparative Morphology of the Gonopodium of Goodeid Fishes Clarence L. Turner Wartburg College Gullermo Mendoza Grinnell College Rebecca Reiter Grinnell College Copyright © Copyright 1962 by the Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Turner, Clarence L.; Mendoza, Gullermo; and Reiter, Rebecca (1962) "Development and Comparative Morphology of the Gonopodium of Goodeid Fishes," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science: Vol. 69: No. 1 , Article 87. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol69/iss1/87 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Turner et al.: Development and Comparative Morphology of the Gonopodium of Goode 1962] SELFINC OF H. NANA 571 Schiller, E. L. 1959c. Experimental studies on morphological variation in the cestode genus Hymenolepis. III. X-irradiation as a mechanism for facilitating analyses in H.. nana. Exp. Par. 8-427-470. Voge, M., and Heyneman, D. 1957. Development of Hymenolepis nana and Ii ymcnolepis dimi1111ta ( Cestoda: Hymenolepididae) in the inter mediate host Tribolium confusum. University of California Publications in Zoology .59:549-579. Voge, M., and Heyneman, D. 1958. Effect of high temperature on the larval development of Hymenolepis nana and Hymenolepis diminuta ( Cestoda: Cyclophyllidea).