Implementation of the Yogyakarta Principles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European Social Charter and Its Supervision Opportunities, Concerns, and the Role of the Ioe

INFORMATION PAPER INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATION OF EMPLOYERS THE EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER AND ITS SUPERVISION OPPORTUNITIES, CONCERNS, AND THE ROLE OF THE IOE CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 2 1. THE SUPERVISION OF THE CHARTER .................................. 3 A. REGULAR REPORTING ...............................................................3 B. THE COLLECTIVE COMPLAINT PROCEDURE ...........................5 C. LEGAL VALUE OF THE DETERMINATIONS RELATED TO THE CHARTER ......................................................5 2. IOE ROLE: OPPORTUNITIES AND CONCERNS .....................6 A. THE SUPERVISION OF THE CHARTER ......................................6 B. THE ROLE OF THE ECSR .............................................................6 C. THE ADDED VALUE OF THE IOE TO THE ENTIRE SYSTEM......7 3. CONCLUSIONS ..........................................................................7 ANNEX I: ECSR INTERPRETATIONS THAT NEGATIVELY IMPACT THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY ..................8 Executive Summary THIS INFORMATION PAPER PROVIDES AN INSIGHT INTO THE CONTENT OF THE EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER (ESC), THE WAY IN WHICH IT IS SUPERVISED, AND THE WORKING METHODS OF THE EUROPEAN COMMITTEE OF SOCIAL RIGHTS (ECSR), WHICH IS TASKED WITH THE CHARTER SUPERVISION. IT HIGHLIGHTS THE OPPORTUNITIES AND CONCERNS FOR THE IOE AND ITS MEMBERS ARISING FROM THE SUPERVISION OF THE ESC. The ESC guarantees social and political -

Cp-Cajp-Inf 166-12 Eng.Pdf

PERMANENT COUNCIL OF THE OEA/Ser.G ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES CP/CAAP-INF. 166/12 23 April 2012 COMMITTEE ON JURIDICAL AND POLITICAL AFFAIRS Original: Spanish SEXUAL ORIENTATION, GENDER IDENTITY, AND GENDER EXPRESSION: KEY TERMS AND STANDARDS [Study prepared by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights "IACHR" pursuant to resolution AG/RES 2653 (XLI-O/11): Human Rights, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Identity] INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS COMISIÓN INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS COMISSÃO INTERAMERICANA DE DIREITOS HUMANOS COMISSION INTERAMÉRICAINE DES DROITS DE L’HOMME ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES WASHINGTON, D.C. 2 0 0 0 6 U.S.A. April 23, 2012 Re: Delivery of the study entitled “Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Gender Expression: Key Terms and Standards” Excellency: I have the honor to address Your Excellency on behalf of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and to attach the document entitled Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Gender Expression: Key Terms and Standards, which will be available in English and Spanish. This paper was prepared at the request of the OAS General Assembly, which, in resolution AG/RES. 2653 (XLI-O/11), asked the IACHR to prepare a study on “the legal implications and conceptual and terminological developments as regards sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression.” The IACHR remains at your disposal for any explanation or further details you may require. Accept, Excellency, renewed assurances of my highest consideration. Mario López Garelli on behalf of the Executive Secretary Her Excellency Ambassador María Isabel Salvador Permanent Representative of Ecuador Chair of the Committee on Juridical and Political Affairs Organization of American States Attachment SEXUAL ORIENTATION, GENDER IDENTITY AND GENDER EXPRESSION: SOME TERMINOLOGY AND RELEVANT STANDARDS I. -

LGBT Global Action Guide Possible

LGBT GLOBAL ACTION GUIDE UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST UNITED NATIONS OFFICE 777 UN Plaza, Suite 7G, New York, NY 10017 USA thanks The Unitarian Universalist United Nations Office wishes to thank the Arcus Foundation for its support which has made the research, writing UU-UNO Staff: and production of this LGBT Global Action Guide possible. While the UU-UNO was very active on the LGBT front in 2008, it was the Arcus Bruce F. Knotts Foundation grant, which began in 2009, that made it possible to Executive Director greatly enhance our LGBT advocacy at the United Nations and to far more effectively engage Unitarian Universalists and our friends in the Celestine Cox Office Coordinator work to end the horrible oppression (both legal and extra-legal) which governments allow and/or promote against people because of their Holly Sarkissian sexual orientation and gender identity. Envoy Outreach Coordinator It is our hope that this guide will prepare you to combat the ignorance Marilyn Mehr that submits to hate and oppression against people not for what they Board President have done, but for who they are. All oppression based on identity (racial, gender, ethnic, sexual orientation, religion, etc.) must end. Many Authors: hands and minds went into the production of this guide. In addition to the Arcus Foundation support, I want to acknowledge the staff, board, Diana Sands interns and friends of the Unitarian Universalist United Nations Office who made this guide possible. I want to acknowledge the work done Geronimo Desumala by the UU-UNO LGBT Associate, Diana Sands, LGBT Fellow Geronimo Margaret Wolff Desumala, III, LGBT intern Margaret Wolff, UU-UNO Board President, Marilyn Mehr, Ph.D., there are many more who should be thanked; Contributors: people who work at the UU-UNO and those who work with us. -

The Right to Health and the European Social Charter

THE RIGHT TO HEALTH AND THE EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER March 2009 Information document prepared by the secretariat of the ESC1 The European Social Charter (ESC) complements the European Convention on Human Rights in the field of economic and social rights. It guarantees various fundamental rights and freedoms and, through a supervisory mechanism based on a system of collective complaints and national reports, ensures that they are implemented and observed by States Parties. It was recently revised and the 1996 Revised European Social Charter is gradually replacing the original 1961 Charter. The rights enshrined in the Charter concern housing, health, education, employment, social protection, the free movement of persons and non- discrimination. In either its original version or its revised 1996 version, the Charter has been signed by all 47 member states of the Council of Europe and ratified by 402 of them. The European Committee of Social Rights (ECSR) ascertains whether countries have honoured the undertakings set out in the Charter. The function of the ECSR is to judge the conformity of national law and practice with the Charter. Its fifteen independent and impartial members are elected by the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers for a period of six years, renewable once. The Charter has several provisions which guarantee, expressly or implicitly, the right to health. Article 11 covers numerous issues relating to public health, such as food safety, protection of the environment, vaccination programmes and alcoholism. Article 3 concerns health and safety at work. The health and well- being of children and young persons are protected by Articles 7 and 17. -

En En Amendments 80

European Parliament 2019-2024 Committee on Employment and Social Affairs 2020/0310(COD) 18.5.2021 AMENDMENTS 80 - 918 Draft report Dennis Radtke, Agnes Jongerius (PE689.873v02-00) Adequate minimum wages in the European Union Proposal for a directive (COM(2020)0682 – C9-0337/2020 – 2020/0310(COD)) AM\1231713EN.docx PE692.765v02-00 EN United in diversityEN AM_Com_LegReport PE692.765v02-00 2/443 AM\1231713EN.docx EN Amendment 80 Johan Danielsson, Heléne Fritzon Proposal for a directive – Proposal for a rejection The European Parliament rejects [the Commission proposal]. Or. en Amendment 81 Jessica Polfjärd, Sara Skyttedal, Tomas Tobé, Arba Kokalari, Jörgen Warborn, David Lega, Markus Ferber Proposal for a directive – Proposal for a rejection — The European Parliament rejects [the Commission proposal]. Or. en Amendment 82 Nikolaj Villumsen, Malin Björk, Marianne Vind Proposal for a directive – Proposal for a rejection The European Parliament rejects [the Commission proposal]. Or. en Justification TFEU 153(5) states that the EU has no competence, when it comes to pay: "The provisions of this Article shall not apply to pay […]". Therefore, the proposal for a Directive on Minimum wages is contrary to the Treaty provisions, and cannot be accepted. In addition, this Directive AM\1231713EN.docx 3/443 PE692.765v02-00 EN threatens the Danish and Swedish labour market models, which have proven to be successful in ensuring increases in real wages and in protecting workers rights. Finally, we do not believe that EU legislation on minimum wages will solve the problems with much too low wage levels in the EU Amendment 83 Sandra Pereira Proposal for a directive Title 1 a (new) Text proposed by the Commission Amendment The European Parliament rejects the Commission proposal. -

Handbook on European Non-Discrimination Law

10.2811/11978 TK-30-11-003-EN-C Handbook Handbook on European non-discrimination law Handbook on European European non-discrimination law, as constituted by the EU non-discrimination directives, and Article 14 of and Protocol 12 to the European Convention on Human Rights, prohibits discrimination across a range of contexts and a range of grounds. This Handbook examines European non-discrimination law stem- ming from these two sources as complementary systems, drawing on them interchangeably to the extent that they overlap, while highlighting differences where these exist. With the impressive body of case-law developed by the European Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice of the European Union in the field of non-discrimination, it seemed useful to present, in an accessible way, a handbook with a CD-Rom intended for legal practitioners in the EU and Council of Europe Member States and be- yond, such as judges, prosecutors and lawyers, as well as law-enforcement officers. Handbook on European non-discrimination law EuropEan union agEncy for fundamEntal rigHts Schwarzenbergplatz 11 - 1040 Vienna - Austria Tel. +43 (1) 580 30-60 - Fax +43 (1) 580 30-693 fra.europa.eu - [email protected] ISBN 978–92–871–9995–9 EuropEan court of Human rigHts council of EuropE 67075 Strasbourg Cedex - France Tel. +33 (0) 3 88 41 20 18 - Fax +33 (0) 3 88 41 27 30 echr.coe.int - [email protected] © European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2010. European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Council of Europe, 2010. European Court of Human Rights - Council of Europe The manuscript was finalised in July 2010. -

I. Introduction

GENERAL REPORT I. Introduction 1. The Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations, appointed by the Governing Body of the International Labour Office to examine the information and reports submitted under articles 19, 22 and 35 of the Constitution by States Members of the International Labour Organization on the action taken with regard to Conventions and Recommendations held its 70th Session in Geneva from 25 November to 10 December 1999. The Committee has the honour to present its report to the Governing Body. 2. The composition of the Committee is as follows: Mr. Anwar Ahmad Rashed AL-FUZAIE (Kuwait), Professor of Private Law of the University of Kuwait; Deputy Vice-President of the Research University of Kuwait; attorney; member of the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC); member of the Higher Consultative Committee on the Application of Islamic Law (Palace of the Emir of Kuwait); former Director of Legal Affairs of the Municipality of Kuwait; former Adviser to the Embassy of Kuwait (Paris). Ms. Janice R. BELLACE (United States), Samuel Blank Professor, Professor of Legal Studies and Management, and Associate Dean of the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania; President, Singapore Management University; Senior Editor, Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal; member of the Executive Board of the US branch of the International Society of Labour Law and Social Security; member of the Public Review Board of the United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural -

Celebrating 10 Years of the Yogyakarta Principles What Have We Learnt and Where to Now?

Celebrating 10 years of the Yogyakarta Principles What have we learnt and where to now? Report of the Conference, Bangkok, 25-26 April 2017 The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the APF concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Celebrating 10 years of the Yogyakarta Principles: What have we learnt and where to now? © Copyright Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions and United Nations Development Programme August 2017 No reproduction is permitted without prior written consent from the APF or the UNDP. Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions GPO Box 5218 Sydney NSW 1042 Australia Email: [email protected] Web: www.asiapacificforum.net United Nations Development Programme Bangkok Regional Hub 3rd Floor, United Nations Service Building Rajdamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200 Thailand Email: [email protected] Web: www.asia-pacific.undp.org Photographs by the Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions and the United Nations Development Programme. Report of the Conference Contents Abbreviations 3 Acknowledgements 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Objectives and outcomes of the Conference 6 2.1. Objectives 6 2.2. Expected outcomes 6 3. Structure and themes of the Conference 7 3.1. Past 7 3.2. Present 7 3.3. Future 8 3.4. Working method of the Conference 8 4. Summary of proceedings -

European Social Charter

091015 PREMS European Social CharterEuropean European Social Charter Collected texts (7th edition) Updated: 1st January 2015 – Collected texts – Collected (7th edition) www.coe.int/socialcharter European Social Charter Collected texts (7th edition) (updated to 1st January 2015) Council of Europe Contents I. BASIC TEXTS 9 A. European Social Charter and Protocols 9 1. European Social Charter of 1961 9 2. Additional Protocol of 1988 25 3. Amending Protocol of 1991 31 4. Additional Protocol of 1995 providing for a system of collective complaints 35 B. Revised European Social Charter of 1996 38 II. SIGNATURES, RATIFICATIONS, DECLARATIONS AND RESERVATIONS 65 A. Signatures and ratifications of the 1961 Charter, its Protocols and the European Social Charter (Revised) 66 B. Tables of accepted provisions 69 C. Reservations and declarations 79 1. Reservations and declarations relating to the European Social Charter (1961) 79 2. Reservations and declarations relating to the 1988 Additional Protocol 97 3. Reservations and declarations relating to the 1991 Amending Protocol 100 4. Reservations and declarations relating to the 1995 Additional Protocol providing for a system of collective complaints 101 5. List of declarations, reservations and other communications related to the revised European Social Charter (1996) 101 III. EXPLANATORY REPORTS 129 A. Explanatory report to the 1988 Additional Protocol 129 B. Explanatory report to the 1991 Amending Protocol 138 C. Explanatory report to the 1995 Protocol 145 D. Explanatory report to the revised European Social Charter 153 IV. EUROPEAN COMMITTEE OF SOCIAL RIGHTS 173 A. Composition 173 B. Election of members of the Committee 174 1. Increase in the number of members from seven to nine 174 2. -

An Activist's Guide to the Yogyakarta Principles

An Activist’s Guide to The Yogyakarta Principles Guide to The Yogyakarta An Activist’s The Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity An Activist’s Guide to The Yogyakarta Principles Section 1 Overview and Context In 2006, in response to well- documented patterns of abuse, a distinguished group of international human rights experts met in Yogyakarta, Indonesia to outline a set of international principles relating to sexual orientation YogYakarta, and gender identity. IndoneSIa The result is the Yogyakarta Principles: a universal guide to human rights which affirm binding international legal standards with which all States must comply. They promise a different future where all people born free and equal in dignity and rights can fulfil that precious birthright. 2 An Activist’s Guide to The Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity In November 2006, we were honored to This Activist’s Guide is a tool for those Foreword serve as co-chairs of a four-day meeting who are working to create change and at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, build on the momentum that has already Indonesia. That meeting culminated a begun around the Yogyakarta Principles. We all have the same human rights. drafting process among twenty-nine In local neighborhoods and international Whatever our sexual orientation, gender international human rights experts organisations, activists of all sexual who identified the existing state of orientations and gender identities are a identity, nationality, place of residence, sex, international human rights law in relation vital part of the international human rights to issues of sexual orientation and gender system, serving as monitors, educators, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, identity. -

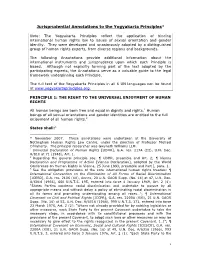

Jurisprudential Annotations to the Yogyakarta Principles*

Jurisprudential Annotations to the Yogyakarta Principles* Note: The Yogyakarta Principles reflect the application of binding international human rights law to issues of sexual orientation and gender identity. They were developed and unanimously adopted by a distinguished group of human rights experts, from diverse regions and backgrounds. The following Annotations provide additional information about the international instruments and jurisprudence upon which each Principle is based. Although not explicitly forming part of the text adopted by the participating experts, the Annotations serve as a valuable guide to the legal framework underpinning each Principle. The full text of the Yogyakarta Principles in all 6 UN languages can be found at www.yogyakartaprinciples.org. PRINCIPLE 1: THE RIGHT TO THE UNIVERSAL ENJOYMENT OF HUMAN RIGHTS All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.1 Human beings of all sexual orientations and gender identities are entitled to the full enjoyment of all human rights.2 States shall:3 * November 2007. These annotations were undertaken at the University of Nottingham Human Rights Law Centre, under the direction of Professor Michael O’Flaherty. The principal researcher was Gwyneth Williams LLM. 1 Universal Declaration of Human Rights [UDHR], G.A. res. 217A (III), U.N. Doc. A/810 at 71 (1948), Art. 1. 2 Regarding the general principle see: ¶ UDHR, preamble and Art. 2; ¶ Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action [Vienna Declaration], adopted by the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, 25 June 1993, preamble and Part I, para. 1. 3 See the obligation provisions of the core international human rights treaties: ¶ International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination [ICERD], G.A. -

How Could the Yogyakarta Principles Help Improve the Situation Of

How could the Yogyakarta Principles help improve the situation of transgender people, when examined in the framework of existing bodies of international non-discrimination norms? Alexandra PISA, ANR 835165 University of Tilburg International and European Public Law, Human Rights Track Supervising professors: S.J. Rombouts Stefanie Jansen 1 Table of contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................... .1 1. Chapter I – A general view of the 'Yogyakarta Principles' …............................................................... 1 1. What are the Yogyakarta Principles and what is their role?........................................................... 3 2. What is their legal status?.............................................................................................................. 4 3. What do the principles contain?..................................................................................................... 6 4. How were the Principles received by the international community?................................................................................................................................... 8 2. Chapter II – Comparing the Principles with existing international legal norms.................................. 13 1. Are the 'Yogyakarta Principles' derived from existing international legal norms?.........................................................................................................................................