Children and Aggressive Toys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toy Gun Eye Injuries – Eye Protection Needed Helsinki Ocular Trauma Study

Acta Ophthalmologica 2018 Toy gun eye injuries – eye protection needed Helsinki ocular trauma study Anna-Kaisa Haavisto, Ahmad Sahraravand, Paivi€ Puska and Tiina Leivo, University of Helsinki and Helsinki University Eye Hospital, Helsinki, Finland ABSTRACT. irideal tear and changes in intraocular Purpose: We report the epidemiology, findings, treatment, long-term outcome pressure (IOP) (Fleischhauer et al. and use of resources for eye injuries caused by toy guns in southern Finland. 1999; Saunte & Saunte 2006; Ram- Methods: All new patients injured by toy guns in one year (2011–2012) and stead et al. 2008; Kratz et al. 2010; treated at Helsinki University Eye Hospital were included. Follow-ups occurred Jovanovic et al. 2012; Haavisto et al. at 3 months and 5 years. 2017). Globe ruptures have been Results: Toy guns caused 15 eye traumas (1% of all eye traumas). Most patients reported from paintballs and also a were male (n = 14) and children aged under 16 years (n = 13). Toy guns few cases from airsoft guns (Greven & = = = Bashinsky 2006; Adyanthaya et al. involved were airsoft guns (n 12), pea shooters (n 2) and paintball (n 1). Eleven patients did not use protective eyewear, and four patients discontinued 2012; Jovanovic et al. 2012; Nemet et al. 2016). Optic neuropathies have their use during the game. Seven patients were not active participants in the also arisen from paintballs (Thach game. Blunt ocular trauma was the primary diagnosis in 13 patients and corneal et al. 1999). Traumatic glaucoma may abrasion in two. Seven patients had retinal findings. In the 5-year follow-up, present even years after a blunt ocular eight of 15 patients had abnormal ocular findings: three had artificial intraocular trauma (Kaufman & Tolpin 1974; lens, two iridodialysis, and one each retinal plomb, mydriasis or iris tear. -

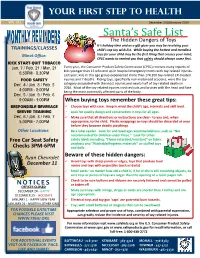

Santass Safe List

Your First Step To Health VOL. 19-1 December 2018/January 2019 Santa’s Safe List The Hidden Dangers of Toys It’s holiday time and as a gift giver you may be receiving your TRAININGS/CLASSES child’s top toy wish list. While buying the hottest and trendiest Minot Office: toys for your child may be the first thing that crosses your mind, CPSC wants to remind you that safety should always come first. Every year, the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) receives many reports of kids younger than 15 who end up in hospital emergency rooms with toy-related injuries. Last year, kids in this age group experienced more than 174,100 toy-related ER-treated injuries and 7 deaths. Riding toys, specifically non-motorized scooters, were the toy category associated with the most injuries and nearly half of toy-related deaths in 2016. Most of the toy-related injuries involved cuts and bruises with the head and face being the most commonly affected parts of the body. When buying toys remember these great tips: Choose toys with care. Keep in mind the child’s age, interests and skill level. Look for quality design and construction in toys for all ages. Make sure that all directions or instructions are clear– to you and, when appropriate, to the child. Plastic wrappings on toys should be discarded at once before they become deadly playthings. Other Locations: Be a label reader. Look for and heed age recommendations, such as “Not recommended for children under three.” Look for other Free Car Seat Safety safety labels including: “Flame retardant/resistant” on fabric products and “Washable/hygienic materials” on stuffed toys Checks 3PM-6PM and dolls. -

Toy Gun Manufacturers: a New Target for Negligent Marketing Liability

TOY GUN MANUFACTURERS: A NEW TARGET FOR NEGLIGENT MARKETING LIABILITY Cynthia A. Brown* I. INTRODUCTION Modern American history chronicles the 1990s and 2000s as decades imbued with high-profile violent events that left a wide wake of injury, maiming and death.1 Throughout the years between 1990 and 2010, public exposure highlighted brutalities occurring across the United States. The decade’s deadly incidents poignantly portrayed by the media, the mass of violent acts receiving less media attention, particularly youth offender violence, and the spread of violent crime from the city centers to the suburbs and rural areas2 prompted health experts to increasingly characterize violence in the 1990s as a “public health epidemic.”3 Unfortunately, the decade that followed ushered in the 21st century with little in the way of inoculation against crime. The century began with the unimaginable events of 9/11 and a new era in high-profile violence. With the world watching, America endured the terrorists’ attacks in Washington, D.C., New York and Pennsylvania, and America experienced a new dimension of vulnerability. It is, therefore, not surprising that the tragic outcomes of two decades of expansive media coverage of extreme violence energized both gun control advocates and second amendment proponents, intensifying an already heated gun control debate. Civil suits also grew in number as victims and survivors demanded accountability. Many plaintiffs targeted gun manufacturers more often as some companies’ marketing strategies revealed intentional appeals to individuals with criminal intentions. Negligent marketing theory provided a novel legal approach directed at weapons manufacturers and distributors that achieved limited success. -

The Wild Child: Children Are Freaks in Antebellum Novels

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2013 The Wild Child: Children are Freaks in Antebellum Novels Heathe Bernadette Heim Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1711 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Wild Child: Children are Freaks in Antebellum Novels by Heather Bernadette Heim A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2013 Heim ii Heim © 2013 HEATHER BERNADETTE HEIM All Rights Reserved iii Heim This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Hildegard Hoeller_______________________ __________ ______________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Mario DiGangi__________________________ ___________ ______________________________________ Date Executive Officer Hildegard Hoeller______________________________ William P. Kelly_______________________________ Marc Dolan___________________________________ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Heim Abstract The Wild Child: Children are Freaks in Antebellum Novels by Heather Bernadette Heim Advisor: Professor Hildegard Hoeller This dissertation investigates the spectacle of antebellum freak shows and focuses on how Phineas Taylor Barnum’s influence permeates five antebellum novels. The study concerns itself with wild children staged as freaks in Margaret by Sylvester Judd, City Crimes by George Thompson, The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe and Our Nig by Harriet Wilson. -

Dangerous Weapons Bill: Draft

STAATSKOERANT, 2 SEPTEMBER 2011 No.34579 3 GENERAL NOTICE NOTICE 606 OF 2011 DEPARTMENT OF POLICE DRAFT DANGEROUS WEAPONS BILL, 2011 Following the decision of the Constitutional Court in the matter of S v Thunzi and S v Mlonzi (Case CCT/81/09), the Minister of Police intends to introduce a draft Dangerous Weapons Bill, 2011, to Parliament, in order to repeal and substitute the Dangerous Weapons Acts in operation in the areas of the erstwhile Republics of South Africa, Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei, and to provide for matters connected therewith. The attached draft Bill is hereby submitted for public comments, in order to finalise it for submission to Cabinet to obtain approval to introduce the Bill to Parliament. Interested persons are invited to submit written comments on the draft Bill within 30 days from the date of publication of this notice to: Postal Address: Major General PC Jacobs Legal Services South African Police Service Private Bag X94 PRETORIA 0001 Street Address: Room No. 340 3rd Floor Presidia Building 255 Pretorius Street Cnr. Paul Kruger and Pretorius Street PRETORIA 0001 E-mail: [email protected] 4 No.34579 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 2 SEPTEMBER 2011 REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA DANGEROUS WEAPONS BILL (As introduced in the National Assembly (proposed section 75); explanatory summary of Bill published in Government Gazette No. ............. of ............. 2011) (The English text is the official text of the Bill) (MINISTER OF POLICE) [B -2011] STAATSKOERANT, 2 SEPTEMBER 2011 No. 34579 5 BILL To provide for certain prohibitions and restrictions in respect of the import, possession, manufacture, sale or supply of certain objects; to repeal and substitute the Dangerous Weapons Acts in operation in the areas of the erstwhile Republics of South Africa, Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei, as those Republics were constituted immediately before 27 April 1994; and to provide for matters connected therewith. -

Aryan Enterprises

+91-8048844515 Aryan Enterprises https://www.indiamart.com/aryan-enterprisesdelhi/ We “Aryan Enterprises” are a leading Wholesaler of a wide range of Photo frame, Table Lamp G, Thermometer, etc. About Us Established as a Proprietor firm in the year 2019 at Old Mustafabad (Delhi, India), we “Aryan Enterprises” are a leading Wholesaler of a wide range of Photo frame, Table Lamp G, Thermometer, etc. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/aryan-enterprisesdelhi/profile.html KIDS TOYS O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Kids Toys Car Kids toys Kids Home Toy Super Hero Toys GUN TOYS O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Toy Gun Kids Toys Musical Gun Toys Airsoft Toy Gun FLYING TOYS O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Kids Drone Flying toys Flying toys Flying Helicopter Toy KIDS DRONE O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Kids Drone Toy Flying Drones Camera Drone Drone Camera MAGIC MIRROR O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Round Magic Mirror Magic Mirror Round Magic Mirror Magic Mirror Photo Frame REMOTE CONTROL CAR TOY O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Remote Control Car Stunt Car Toys Remote Control Car Toy Kids Car Toys RACING CAR TOY O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Kids Toys Kids Toys Car Race Car Toys Race Car Toys KID TOYS O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Strike Gun Concept Racing Car Truck Toys For Kids Kids Gun Toy BABY DOLLS O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Kids Dolls Baby Dolls Kids Dolls ROBOT TOY O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Robot Toy Toy Robot Kids Robot Toys KIDS REMOTE CAR O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Remote Car Toys Remote Car Toys Remote Car Toys -

Take the Shop Local Pledge & Win!

2— Last Minute Gift Guide 2016 Dear Santa: doll backpack. Dear Santa: xbox, I want a call of duty game I want a keyboard, Barbie house, Dear Santa: Kaydence I have been a good little boy and a halo game too. American girl doll clothes, fringe I want a cross bow and a toy gun. this year. I would love to have a Colton B. boots and triple bunk doll bed. Colton A. Dear Santa: pedal bike please. Jentry Jones I want a desk, big bear, robot kitty, Trenton W. Dear Santa: Dear Santa: scooter, shopkins, bag, baby stroller I have been a good girl this year. Dear Santa: Can I have the Rhing of fire and and slepover stuff. Dear Santa: So far, I really want a toy pony, I would like a baby doll, fake food, a mastodon? I want a motor bike Melynne The thing I want most is a batman ipad of my own so I can practice a Nabi, a basketball, a deer randa also. castle, play station 4, Nintendo 3D, my school work, a trip with you sled. Casen Dear Santa: clothes and skateboard. to the north pole, and meet all the Zoey Jones I love you. I want American girl dolls, Braiden elves and Mrs. Claus. Thank you Dear Santa: legos and everyone to be happy. for taking the time to read my Dear Santa: I would like a xbox controller, Paityn Dear Santa: letter. P. S. Mommy helped me. I would want some scechers, and play doh, and a toy sniper. Merry I have been a very good girl. -

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 03-22-1915 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 3-22-1915 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 03-22-1915 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 03-22-1915." (1915). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/1242 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , CITY CITY EDITION ALBUQUERQUE MORNING JOURNAL. EDITION TIUKTV-SIXT- II YKAIt V(tl.. CXVXXV. Hit, ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, MONDAY," MARCH 22, 1915, Dally by Ou-rt- or Mnll, 60o a Month. Single Oiplea fto. b ill1.:' Ill SED 8V at t 'oloinlii n, six miles from I'mis, j B MYSTERY OP 30 ZEPPELIN RAID mail,' a huh' tell fci t vv hie hy five GRAPHIC STORY Teutonic Consuls Urge Nationals feet deep and the Harden wall wns overthrown for a distance of eighteen feet. Ill contrast o this, another! li.imh which ,. ,, douse in the- to Quit Country Soon as Possible AXE MURDERS IS PARIS S liile Desdames, in Tal is, merely dent- - DF JOURNEY FROM ed the in. roof Parisians during tlie attack wi re nnahle to distinguish bilWeeii the lie-- j sians n ncwed ihi'ir nllcmpl.s with BELIEVED NEAR LITTLE DAMAGE tonnl ions of t he fa lliug bombs and the POSEN TO SLAV stronger forces. -

Gel Blasters Fact Sheet

FACT SHEET Gel Blasters What is a Gel Blaster? A gel blaster (or gel ball blaster, hydro blaster, gel gun) is a life-like toy gun designed to shoot a gel pellet that has been soaked in water (similar to an Orbeez). Gel blasters are similar to a paintball gun and are becoming more popular for use in activities similar to paintball skirmish and laser tag. Gel blasters are not prohibited in Queensland and do not require a permit or license to keep. They need to be used responsibly and in accordance with relevant laws and requirements (e.g. importation permits, noise, parking, etc.). Please refer to the information below, and visit Council's webpage on Local Laws. Do I need approval? Depending on where you are using gel blasters, and on what scale (i.e. how many people participating, how often), you may need approval from Council. Use Approval Description of proposed development required? Private use No Where gel blasters are being used for skirmish by the resident of a house (Dwelling house) (residents at and their family and/or friends, there is no Council approval required. It is strongly home) recommended that you: • do not advertise your skirmish event on social media, SMS or word of mouth; and • refer to the Party Safe Program information provided by the Queensland Police. Indoor sport Yes Where gel blasters are being used for commercial purposes in an indoor setting the activity is and defined as Indoor sport and recreation. Indoor sport and recreation means the use of recreation premises for a leisure, sport or recreation activity conducted wholly or mainly indoors. -

Airsoft a Nonlethal Form of Firearm Currently Illegal Within Australia

This is a submission to the committee on Personal choice and community impacts This submission deals with Airsoft a Nonlethal form of firearm currently illegal within Australia. Can this be made legal. In 2002 the firearms act was amended in Western Australia to make paintball legal even though it is not a recognised sport in Australia. Meanwhile in the rest of the world it has lead to sports that are enjoyed by hundreds of thousands. Airsoft A brief description of what Airsoft is. Airsoft is a sport that has developed out of what were called BB guns in the 1980’s and early 1990’s. They were developed in Japan due to paintball being illegal in that country. A tagger used in airsoft consists of a simulated weapon made of plastic, Pot- metal or aluminium that ejects a round sphere 6 or 8mm in size made of either plastic or corn starch with a gluten coating (referred to as bio rounds as they break down quickly) with a weight of 0.12 up to 0.42 grams. Airsoft as a sport/recreational activity is enjoyed by 100,000’s around the world. By all ages and sexes. In the attached world map (Appendix A) you may note that every country in the world we would consider peers play the sport of airsoft. In Australia it is not however recognised as a sport due to the current illegal status. However with over 20 publications in half a dozen languages and hundreds of stores online plus the actual reference in Law to the sport of airsoft in both New Zealand’s firearms law and other countries it would be disingenuous to not proscribe it at least the recreational game/sport status that paintball enjoys in this Country. -

Feminist Periodicals

The Un versity o f W scons n System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 21, Number 3, Fall 2001 Published by Phyllis HolmanWeisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian Feminist Periodicals A current listing ofcontents Volume 21, Number 3 Fall 2001 Periodical literature is the cutting edge ofwomen's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the U(liversity of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum offeminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to ajournal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table ofcontents pages from currentissues ofmajor feministjournals are reproduced in each issue of Feminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first pUblication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. U.S. subscription price(s). 4. Subscription address. 5. Current editor. 6. Editorial address (if different from SUbscription address). -

NERF ULTRA ONE Price: $49.99 Manufacturer Or Distributor

W.A.T.C.H.’S 2019 Nominees for “10 WORST TOYS” NERF ULTRA ONE Price: $49.99 Manufacturer or Distributor: Hasbro Retailer(s): Target.com, Walmart.com, Hasbro.com Age Recommendation: “AGES 8+” Warnings: “CAUTION: Do not aim at eyes or face. TO AVOID INJURY: Use only with official NERF darts….”, and other cautions/warnings. HAZARD: POTENTIAL FOR EYE INJURIES! W.A.T.C.H. OUT! The manufacturer of this dart “blaster” boasts that the ammunition “FIRES UP TO 120 FT” with “POWERFUL SPEED” making this the “FARTHEST FLYING NERF DART. EVER.” The darts provided can shoot with enough force to potentially cause eye injuries. Of note at least one retailer sells this “motorized” toy weapon alongside “Nerf Battle Goggles, a “toy” which “…does not provide protection.” W.A.T.C.H.’S 2019 Nominees for “10 WORST TOYS” SPIKE THE FINE MOTOR HEDGEHOG Price: $17.99 Manufacturer or Distributor: Learning Resources, Inc. Retailer(s): Magic Beans, Kohls.com, Amazon.com, eBay.com, Target.com, Walmart.com Age Recommendation: “18+ Months” Warnings: None. HAZARD: POTENTIAL FOR INGESTION AND CHOKING INJURIES! W.A.T.C.H. OUT! This “hedgehog”, sold for oral-age children as young as 18 months old, comes with twelve removable, rigid-plastic “quills” measuring approximately 3 ½ inches long. The quills can potentially be mouthed and occlude a child’s airway. W.A.T.C.H.’S 2019 Nominees for “10 WORST TOYS” BUNCHEMS BUNCH’N BUILD Price: $16.58 Manufacturer or Distributor: Spin Master LTD. Retailer(s): Amazon.com, Michael’s, Michaels.com, Walmart.com, Nordstromrack.com, Lightinthebox.com Age Recommendation: “4+” Warnings: “CAUTION: Keep away from hair.