Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos Santana on New 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection Featuring Five Limited-Edition Signature and Replica Guitars Exclusive Guitar Collection Developed in Partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender®, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars to Benefit Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Centre Antigua Limited Quantities of the Crossroads Guitar Collection On-Sale in North America Exclusively at Guitar Center Starting August 20 Westlake Village, CA (August 21, 2019) – Guitar Center, the world’s largest musical instrument retailer, in partnership with Eric Clapton, proudly announces the launch of the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection. This collection includes five limited-edition meticulously crafted recreations and signature guitars – three from Eric Clapton’s legendary career and one apiece from fellow guitarists John Mayer and Carlos Santana. These guitars will be sold in North America exclusively at Guitar Center locations and online via GuitarCenter.com beginning August 20. The collection launch coincides with the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Festival in Dallas, TX, taking place Friday, September 20, and Saturday, September 21. Guitar Center is a key sponsor of the event and will have a strong presence on-site, including a Guitar Center Village where the limited-edition guitars will be displayed. All guitars in the one-of-a-kind collection were developed by Guitar Center in partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars, drawing inspiration from the guitars used by Clapton, Mayer and Santana at pivotal points throughout their iconic careers. The collection includes the following models: Fender Custom Shop Eric Clapton Blind Faith Telecaster built by Master Builder Todd Krause; Gibson Custom Eric Clapton 1964 Firebird 1; Martin 000-42EC Crossroads Ziricote; Martin 00-42SC John Mayer Crossroads; and PRS Private Stock Carlos Santana Crossroads. -

The Blue Review Literature Drama Art Music

Volume I Number III JULY 1913 One Shilling Net THE BLUE REVIEW LITERATURE DRAMA ART MUSIC CONTENTS Poetry Rupert Brooke, W.H.Davies, Iolo Aneurin Williams Sister Barbara Gilbert Cannan Daibutsu Yone Noguchi Mr. Bennett, Stendhal and the ModeRN Novel John Middleton Murry Ariadne in Naxos Edward J. Dent Epilogue III : Bains Turcs Katherine Mansfield CHRONICLES OF THE MONTH The Theatre (Masefield and Marie Lloyd), Gilbert Cannan ; The Novels (Security and Adventure), Hugh Walpole : General Literature (Irish Plays and Playwrights), Frank Swinnerton; German Books (Thomas Mann), D. H. Lawrence; Italian Books, Sydney Waterlow; Music (Elgar, Beethoven, Debussy), W, Denis Browne; The Galleries (Gino Severini), O. Raymond Drey. MARTIN SECKER PUBLISHER NUMBER FIVE JOHN STREET ADELPHI The Imprint June 17th, 1913 REPRODUCTIONS IN PHOTOGRAVURE PIONEERS OF PHOTOGRAVURE : By DONALD CAMERON-SWAN, F.R.P.S. PLEA FOR REFORM OF PRINTING: By TYPOCLASTES OLD BOOKS & THEIR PRINTERS: By I. ARTHUR HILL EDWARD ARBER, F.S.A. : By T. EDWARDS JONES THE PLAIN DEALER: VI. By EVERARD MEYNELL DECORATION & ITS USES: VI. By EDWARD JOHNSTON THE BOOK PRETENTIOUS AND OTHER REVIEWS: By J. H. MASON THE HODGMAN PRESS: By DANIEL T. POWELL PRINTING & PATENTS : By GEO. H. RAYNER, R.P.A. PRINTERS' DEVICES: By the Rev.T. F. DIBDIN. PART VI. REVIEWS, NOTES AND CORRESPONDENCE. Price One Shilling net Offices: 11 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.G. JULY CONTENTS Page Post Georgian By X. Marcel Boulestin Frontispiece Love By Rupert Brooke 149 The Busy Heart By Rupert Brooke 150 Love's Youth By W. H. Davies 151 When We are Old, are Old By Iolo Aneurin Williams 152 Sister Barbara By Gilbert Cannan 153 Daibutsu By Yone Noguchi 160 Mr. -

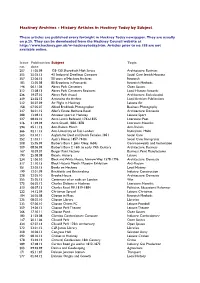

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject

Hackney Archives - History Articles in Hackney Today by Subject These articles are published every fortnight in Hackney Today newspaper. They are usually on p.25. They can be downloaded from the Hackney Council website at http://www.hackney.gov.uk/w-hackneytoday.htm. Articles prior to no.158 are not available online. Issue Publication Subject Topic no. date 207 11.05.09 125-130 Shoreditch High Street Architecture: Business 303 25.03.13 4% Industrial Dwellings Company Social Care: Jewish Housing 357 22.06.15 50 years of Hackney Archives Research 183 12.05.08 85 Broadway in Postcards Research Methods 146 06.11.06 Abney Park Cemetery Open Spaces 312 12.08.13 Abney Park Cemetery Registers Local History: Records 236 19.07.10 Abney Park chapel Architecture: Ecclesiastical 349 23.02.15 Activating the Archive Local Activism: Publications 212 20.07.09 Air Flight in Hackney Leisure: Air 158 07.05.07 Alfred Braddock, Photographer Business: Photography 347 26.01.15 Allen's Estate, Bethune Road Architecture: Domestic 288 13.08.12 Amateur sport in Hackney Leisure: Sport 227 08.03.10 Anna Letitia Barbauld, 1743-1825 Literature: Poet 216 21.09.09 Anna Sewell, 1820-1878 Literature: Novelist 294 05.11.12 Anti-Racism March Anti-Racism 366 02.11.15 Anti-University of East London Radicalism: 1960s 265 03.10.11 Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Females, 1851 Social Care 252 21.03.11 Ayah's Home: 1857-1940s Social Care: Immigrants 208 25.05.09 Barber's Barn 1: John Okey, 1650s Commonwealth and Restoration 209 08.06.09 Barber's Barn 2: 16th to early 19th Century Architecture: -

For Immediate Release March 5, 2004

For Immediate Release March 5, 2004 Contact: Bendetta Roux, New York 212.636.2680 [email protected] Jill Potterton , London 207.752.3121 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S NEW YORK TO OFFER GUITARS FROM ERIC CLAPTON SOLD TO BENEFIT THE CROSSROADS CENTRE IN ANTIGUA “These guitars are the A-Team … What I am keeping back is just what I need to work with. I am selling the cream of my collection.” Eric Clapton, February 2004 Crossroads Guitar Auction Eric Clapton and Friends for the Crossroads Centre June 24, 2004 New York – On June 24, 1999, Christie’s New York organized A Selection of Eric Clapton’s Guitars ~ In Aid of the Crossroads Centre, a sale that became legendary overnight. Exactly five years later, on June 24, 2004, Christie’s will present the sequel when a group of 56 guitars, described by Eric Clapton as “the cream of my collection,” as well as instruments donated by musician friends such as Pete Townshend, will be offered. Featuring iconic instruments such as ‘Blackie’ and the cherry-red 1964 Gibson ES-335, Crossroads Guitar Auction ~ Eric Clapton and Friends for the Crossroads Centre, promises to be a worthy successor to the seminal 1999 sale. The proceeds of the sale will benefit the Crossroads Centre in Antigua. Referring to the selection of guitars that will be offered in this sale, Eric Clapton said: “These guitars are in fact the ones that I kept back from the first auction because I seriously couldn’t consider parting with them at that point … I think they are a really good representation of Rock Culture .. -

The Chemistry Club a Number of Interesting Movies Were Enjoyed by the Chemistr Y Club This Year

Hist The Chronicle Coll CHS of 1942 1942 Edited by the Students of Chelmsford High School 2 ~{ Chelmsford High School Foreword The grcalest hope for Lh<' cider comes f rorn l h<' spiril of 1\mcrirnn youth. E xcmplilit>cl hy the cha r aclcristics of engerne%. f rnnk,wss. amhilion. inili,lli\·c'. and faith. il is one of the uplil'ling factor- of 01 1r li\'CS. \ \ 'iLhoul it " ·e could ,, <'II question th<' f1 1Lurc. \ \ 'ith il we rnusl ha\'C Lh e assurallce of their spirit. \ Ve hope you\\ ill nlld in the f oll o,, ing page:- some incli cnlion of your pasl belief in our young people as well as sornP pncouragcmenl for the rnnlinualion of your faiLh. The Chronicle of 1942 ~ 3 CONTENTS Foreword 2 Con lent 3 ·I 5 Ceo. ' . \\' righl 7 Lucian 11. 13urns 9 r undi y 11 13oard of l:cl ilors . Ser I iors U11dcrgrnd1rnlcs 37 .l11 nior Class 39 Sopho111ore Cb ss ,JO F reshma11 C lass 4 1 S port s 43 /\ct i,·ilies I lumor 59 Autographs 66 Chelmsford High School T o find Llw good in llE'. I've learned lo Lum T o LhosE' \\'ilh w hom my da ily lol is rasl. \ \/hose grncious h111n11n kindness ho lds me fast. Throughout the ycnr I w a nl to learn. T ho1 1gh war may rage and nations overlum. Those deep simplirilies Lhat li\'C and lasl. To M. RIT !\ RY J\N vV e dedicate our yearbook in gra te/ul recognition o/ her genial manner. -

The Fender Custom Shop and “Blackie” Your Questions Answered…

The Fender Custom Shop and “Blackie” Your questions answered… A few days before the launch of the Fender Eric Clapton “Blackie” Reissue, Mike Eldred – Director of Sales and Marketing for the Fender Custom Shop, was interviewed by Guitar Center for his personal account of the “Blackie” Reissue project. GC: So Mike, what’s your role at Fender, and in the Custom Shop specifically? Mike: I’m Director of Sales and Marketing for the FMIC Custom Division, and that encompasses all brands: Tacoma, Guild, Gretsch, Fender, Charvel, Jackson, and the amplifiers. GC: What is it about “Blackie” that makes it so special, even within that special world? Mike: It’s an iconic Stratocaster. The story about the guitar is really such a great story about how Eric bought the guitar--bought several guitars--and then pieced together basically just one guitar from a bunch of different parts. So he actually built the guitar, which is very unique when it comes to iconic guitars like this. A lot of times they’re just bought at a store or something like that. But here, an artist actually built the guitar, and then used it on so many different recordings, and it was so identified with Eric Clapton and his musical legacy. GC: Then, after 35 years of ownership, he offered it up for sale. What did Fender think when they heard that Guitar Center had bought Blackie at auction for almost a million dollars? Mike: Just that we were glad that it was sold to someone we have a relationship with. The concern that we had was that somebody was going to buy it and then just lock it away and that would be that, or some private collector would buy it or something like that. -

WHO's GUITAR Is That?

2013 KBA -BLUES SOCIETY OF THE YEAR CELEBRATING OUR 25TH YEAR IN THIS ISSUE: -Who’s Guitar is That? -The Colorado-Alabama Connection Volume 26 No3 April/May2020 -An Amazing Story -Johnny Wheels Editor- Chick Cavallero -Blues Boosters Partners -CBS Lifetime Achievement WHO’s GUITAR is Award to Mark Sundermeier -CBS Lifetime Achievement That? Award to Sammy Mayfield By Chick Cavallero -CD Reviews –CBS Members Pages Guitar players and their guitar pet names what’s in a name, eh? Not every guitar player names his CONTRIBUTERS TO THIS ISSUE: guitars, heck be pretty hard since some of them have hundreds, and some big stars have Chick Cavallero, Jack Grace, Patti thousands. Still, there have been a few famous Cavallero, Gary Guesnier, Dr. Wayne ones in the Blues World. Most every blues fan Goins, Michael Mark, Ken Arias, Peter knows who Lucille was, B.B. King’s guitar, right? “Blewzzman” Lauro But why? Well, in 1949 BB was a young bluesman playing at a club in Twist, Arkansas that was heated by a half-filled barrel of kerosene in the middle of the dance floor to keep it warm. A fight broke out and the barrel got knocked over with flaming kerosene all over the wooden floor. “It looked like a river of fire, so I ran outside. But when I got on the outside, I realized I left my guitar inside.” B.B. Said he then raced back inside to save the cheap Gibson L-30 acoustic he was playing …and nearly lost his life! The next day he found out the 2 men who started the fight-and fire- had been fighting over a woman named Lucille who worked at that club. -

Urge to Own That Clapton Guitar Is Contagious, Scientists Find - the New York Times Page 1 of 3

Urge to Own That Clapton Guitar Is Contagious, Scientists Find - The New York Times Page 1 of 3 This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. You can order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, please click here or use the "Reprints" tool that appears next to any article. Visit www.nytreprints.com for samples and additional information. Order a reprint of this article now. » March 9, 2011 Urge to Own That Clapton Guitar Is Contagious, Scientists Find By JOHN TIERNEY Why would someone pay $959,500 for a used guitar? That was a difficult enough question in 2004 when Eric Clapton sold his beloved Fender Stratocaster named Blackie. But now, as collectors around the world prepare to bid Wednesday at another charity auction of Mr. Clapton's guitars, the questions are even tougher. Why would someone create a replica of Blackie, complete with every single nick and scratch, including the wear pattern from Mr. Clapton's belt buckle and the burn mark from his cigarettes? And why is that replica expected to fetch at least $20,000 at Wednesday's auction, and probably much more? Fortunately, social scientists have been hard at work on the answers. After conducting experiments and interviewing guitar players and collectors, they have just published papers analyzing ''celebrity contagion'' and ''imitative magic,'' not to mention ''a dynamic cyclical model of fetishization appropriate to an age of mass-production.'' One of their conclusions is that the seemingly illogical yearning for a Clapton relic, even a pseudorelic, stems from an instinct crucial to surviving disasters like the Black Death: the belief that certain properties are contagious, either in a good or a bad way. -

Lyrics and Music

Soundtrack for a New Jerusalem Lyrics and Music By Lily Meadow Foster and Toliver Myers EDITED by Peter Daniel The 70th Anniversary of the National Health Service 1 Jerusalem 1916 England does not have a national anthem, however unofficially the beautiful Jerusalem hymn is seen as such by many English people. Jerusalem was originally written as a preface poem by William Blake to his work on Milton written in 1804, the lyrics were added to music written by Hubert Parry in 1916 during the gloom of WWI when an uplifting new English hymn was well received and needed. Blake was in- spired by the mythical story Jesus, accompanied by Joseph of Arimathea, once came to England. This developed its major theme that of creating a heaven on earth in En- galnd, a fairer more equal country that would abolish the exploitation of working people that was seen in the ‘dark Satin mills’ of the Industrial revolution. The song was gifted by Hubert Parry to the Suffragette movement who were inspired by this vi- sion of equality. 2 Jerusalem William Blake lyrics Hubert Parry Music 1916 And did those feet in ancient time Walk upon England's mountains green? And was the holy Lamb of God On England's pleasant pastures seen? And did the countenance divine Shine forth upon our clouded hills? And was Jerusalem builded here Among those dark Satanic Mills? Bring me my bow of burning gold! Bring me my arrows of desire! Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold! Bring me my chariot of fire! I will not cease from mental fight Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand Till we have built Jerusalem In England's green and pleasant Land Hubert Parry 1916 Words by William Blake 1804 3 Jerusalem 1916 4 Jerusalem 1916 5 Jerusalem 1916 William Blake imagined a time when Britain would be a fairer more equal society. -

A Variety Show from Tagora

Roll-call La Belle Époque is created, directed and performed by: V David Adamson, Joceline Adamson, Ian Bennett, Maimu Berg, Yucel Biricik, David Bousquet, Angela Brewer, David Crowe, Grégoire de Victor, Isabelle Dousset, Catherine Dreyfus, Imogen Hattenville, Louis Hattenville, Nell Hattenville, Paula Hinchy, Pelin Iscan, Banu Karamanoğlu, Selina Kenny, Julia Laffranque, Oscar Laffranque, Tobias Laffranque, Elena Malagoni, Roger Massie, Ann Meyer, Tina Mul- cahy, Bridget O’Loughlin, Maria Oreshkina, Louise Palmer, Simon Palmer, Edmond Perrier, Edouard Per- rier, Lucy Perrier, Maria Psarrou, Sabine Rinck, Milica Sajin, Doris Schaal, Mónica Soler-Pérez, Martin Swit- zer, Janis Symons, Martyn Symons, Andrew Tattersall, Richard Thayer, François Thouvenin, William Valk, Julie Vauboin, Armelle Weber, Julia Whitham, Andrew Wright, Jonah Wright, Liam Wright, Marie- Anne Wright, Martin Wright, Owen Wright. Backstage V Morgane Agez, Dianne Bartsch, Hazel Bastier, Lois Ceredig, Sara Rekar. Wardrobe V Marie-Claude Leroux, with the help of Janis Symons and Julie Vauboin. A variety show Décor V Martyn Symons. from Tagora Technical team V Albin Bernard, Richard Cruse, Hal d’Arpini, Carlos Hernández, Jeannine O’Kane, Rob Simmons. Cube noir Front-of-house/bar Koenigshoffen, V Guido Brockmann, Pelin Iscan, Marloes Kerstens, Michèle Lotz, Claire Massie, Lourd McCabe, Dave Strasbourg Parrott, Milica Sajin. 13-15 December 2013 Acknowledgements Grateful thanks to: Michèle Adamson, Amicale du per- 18-20 December 2013 sonnel du Conseil de l’Europe; Albert Ashok; Pierre Charpilloz; CREPS; Finnish National Gallery, Hel- sinki; Ann and Christopher Grayson; Adrienne and Michael Ingledow; David-Michel Muller; Xavier Schmaltz; Marie-José Schneider; Collectif Trois 14; Ville de Strasbourg V uProgramme The music hall tradition u Tagora asked J.R. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 107 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 107 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 147 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2001 No. 164 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was build upon the past, and by their pray- ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER called to order by the Speaker pro tem- ers and their noble deeds still grace PRO TEMPORE pore (Mr. THORNBERRY). this Nation and its future. The SPEAKER pro tempore. The f Even in this time, sometimes called ‘‘the age of worldwide refugees,’’ You Chair will entertain 1-minute requests DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER still call people to faith and freedom. at the end of the day. PRO TEMPORE Bless the Members of Congress and The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- grant them wisdom as they secure f fore the House the following commu- homeland borders and enact lawful im- nication from the Speaker: migration. The world will be shown a WAIVING POINTS OF ORDER THE SPEAKER’S ROOMS, land where Your promise will be real- AGAINST CONFERENCE REPORT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, ized, faith can be expressed, and all will ON H.R. 2299, DEPARTMENT OF Washington, DC, November 30, 2001. be free. TRANSPORTATION AND RELATED I hereby appoint the Honorable MAC THORNBERRY to act as Speaker pro tempore We still answer Your call, Lord, now AGENCIES APPROPRIATIONS on this day. and forever. Amen. ACT, 2002 J. DENNIS HASTERT, f Speaker of the House of Representatives. Mr. REYNOLDS. Mr. Speaker, by di- rection of the Committee on Rules, I f THE JOURNAL call up House Resolution 299 and ask PRAYER The SPEAKER pro tempore. -

GRAM PARSONS LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

GRAM PARSONS LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. As performed in principal recordings (or demos) by or with Gram Parsons or, in the case of Gram Parsons compositions, performed by others. Gram often varied, adapted or altered the lyrics to non-Parsons compositions; those listed here are as sung by him. Gram’s birth name was Ingram Cecil Connor III. However, ‘Gram Parsons’ is used throughout this document. Following his father’s suicide, Gram’s mother Avis subsequently married Robert Parsons, whose surname Gram adopted. Born Ingram Cecil Connor III, 5th November 1946 - 19th September 1973 and credited as being the founder of modern ‘country-rock’, Gram Parsons was hugely influenced by The Everly Brothers and included a number of their songs in his live and recorded repertoire – most famously ‘Love Hurts’, a truly wonderful rendition with a young Emmylou Harris. He also recorded ‘Brand New Heartache’ and ‘Sleepless Nights’ – also the title of a posthumous album – and very early, in 1967, ‘When Will I Be Loved’. Many would attest that ‘country-rock’ kicked off with The Everly Brothers, and in the late sixties the album Roots was a key and acknowledged influence, but that is not to deny Parsons huge role in developing it. Gram Parsons is best known for his work within the country genre but he also mixed blues, folk, and rock to create what he called “Cosmic American Music”. While he was alive, Gram Parsons was a cult figure that never sold many records but influenced countless fellow musicians, from the Rolling Stones to The Byrds.