The Politics of the CPEC Journal Item

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monday, 20Th November, 2017

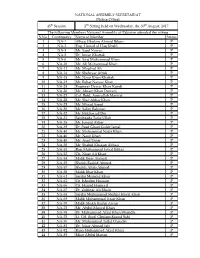

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT (Notice Office) 49th Session 3rd Sitting held on Monday, the 20th November, 2017 The following Members National Assembly of Pakistan attended the sitting S.No. Contituency Name of Member Status 1 NA-1 Alhaaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour P 2 NA-2 Eng. Hamid ul Haq Khalil P 3 NA-3 Mr. Sajid Nawaz P 4 NA-5 Dr. Imran Khattak P 5 NA-6 Mr. Siraj Muhammad Khan P 6 NA-7 Maulana Muhammad Gohar Shah P 7 NA-10 Mr. Ali Muhammad Khan P 8 NA-11 Mr. Mujahid Ali P 9 NA-12 Engineer Usman Khan Tarakai P 10 NA-13 Mr. Aqibullah P 11 NA-15 Mr. Nasir Khan Khattak P 12 NA-17 Dr. Muhammad Azhar Khan Jadoon P 13 NA-18 Mr. Murtaza Javed Abbasi P 14 NA-21 Capt. Retd. Muhammad Safdar P 15 NA-22 Qari Muhammad Yousaf P 16 NA-25 Engineer Dawar Khan Kundi P 17 NA-27 Col. Retd. Amirullah Marwat P 18 NA-28 Mr. Sher Akbar Khan P 19 NA-29 Mr. Murad Saeed P 20 NA-30 Mr. Salim Rehman P 21 NA-32 Mr. Iftikhar ud Din P 22 NA-34 Sahibzada Muhammad Yaqub P 23 NA-35 Mr. Junaid Akbar P 24 NA-36 Mr. Bilal Rehman P 25 NA-37 Mr. Sajid Hussain Turi P 26 NA-40 Mr. Muhammad Nazir Khan P 27 NA-43 Mr. Bismillah Khan P 28 NA-44 Mr. Shahab ud Din Khan P 29 NA-45 Alhaj Shah Jee Gul Afridi P 30 NA-46 Mr. -

YPF Report.Cdr

PERFORMANCE OF YOUNG PARLIAMENTARIANS June 2016 - May 2017 (Fourth Parliamentary Year) NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN FREE AND FAIR ELECTION NETWORK www.fafen.org I www.openparliament.pk I www.parliamentfiles.com +fafenorg @_fafen fafen.org YOUNG MPs SPONSOR 51 LEGISLATIVE PROPOSALS DURING 4TH PARLIAMENTARY YEAR Young lawmakers of MQM excel in annual parliamentary performance scorecard 23 legislators stay mum throughout fourth parliamentary year Aliya Kamran of JUI-F most punctual and Hamza Shehbaz of PML-N least punctual among young lawmakers Pakistan has a large section of young population and their Young Parliamentarians representation in the legislatures has also increased in recent years. Forum (YPF), a platform The Young Parliamentarians Forum (YPF) of the National Assembly established to assist and comprises 78 lawmakers who are below 40 years of age. The annual develop future political performance statistics showed that as many as 55 out of 78 young leadership of the country lawmakers took part in the proceedings of the National Assembly defines “young during the fourth parliamentary year. The remaining lawmakers did not parliamentarians” as “all contribute to the agenda and debates of the House. Majority of these members who are 40 non-participating lawmakers (17) belonged to PML-N while three were years of age or under at associated with PPPP and one each with MQM, PML-F and the time of election”. Independent group. ACTIVE YOUNG LAWMAKERS 43 As 30 29 20 16 14 Number of MN 6 5 3 3 2 Contribution Calling Points of Questions Bills Resolutions Motion under Presentation Amendments Adjournment Matter of to Debates Attention Order (Starred and Rule 259 of Reports to the Rules Motions Public Notices Unstarred) Importance under Rule 87 The data revealed that the young lawmakers mostly contribute agenda in collaboration with their senior colleagues. -

Fafen Election

FAFEN ELECTION . 169 NA and PA constituencies with Margin of Victory less than potentially Rejected Ballots August 3, 2018 The number of ballot papers excluded increase. In Islamabad Capital Territory, from the count in General Elections 2018 the number of ballots excluded from the surpassed the number of ballots rejected count are more than double the in General Elections 2013. Nearly 1.67 rejected ballots in the region in GE-2013. million ballots were excluded from the Around 40% increase in the number of count in GE-2018. This number may ballots excluded from the count was slightly vary after the final consolidated observed in Balochistan, 30.6 % increase result is released by the Election in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa including Commission of Pakistan (ECP) as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas ballots excluded from the count at the (FATA), 7% increase in Sindh and 6.6% polling station level by Presiding Officers increase in Punjab. are to be reviewed by the Returning The following table provides a Officers during the consolidation comparison of the number of rejected proceedings, who can either reject them National Assembly ballot papers in each or count them in favor of a candidate if province/region during each of the past excluded wrongly. four General Elections in 2002, 2008, 2013 The increase in the number of ballots and 2018. Although the rejected ballots excluded from the count was a have consistently increase over the past ubiquitous phenomenon observed in all four general elections, the increase was provinces and Islamabad Capital significantly higher in 2013 than 2008 Territory with nearly 11.7% overall (54.3%). -

S.No. Contituency Name of Member Status 1 NA-1 Alhaaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour P 2 NA-2 Eng

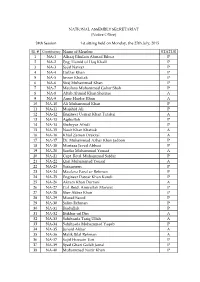

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT (Notice Office) 45th Session 2nd Sitting held on Wednesday, the 30th August, 2017 The following Members National Assembly of Pakistan attended the sitting S.No. Contituency Name of Member Status 1 NA-1 Alhaaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour P 2 NA-2 Eng. Hamid ul Haq Khalil P 3 NA-3 Mr. Sajid Nawaz P 4 NA-5 Dr. Imran Khattak P 5 NA-6 Mr. Siraj Muhammad Khan P 6 NA-10 Mr. Ali Muhammad Khan P 7 NA-11 Mr. Mujahid Ali P 8 NA-14 Mr. Shehryar Afridi P 9 NA-15 Mr. Nasir Khan Khattak P 10 NA-19 Mr. Babar Nawaz Khan P 11 NA-25 Engineer Dawar Khan Kundi P 12 NA-26 Mr. Akram Khan Durrani P 13 NA-27 Col. Retd. Amirullah Marwat P 14 NA-28 Mr. Sher Akbar Khan P 15 NA-29 Mr. Murad Saeed P 16 NA-30 Mr. Salim Rehman P 17 NA-32 Mr. Iftikhar ud Din P 18 NA-33 Sahibzada Tariq Ullah P 19 NA-35 Mr. Junaid Akbar P 20 NA-39 Dr. Syed Ghazi Gulab Jamal P 21 NA-40 Mr. Muhammad Nazir Khan P 22 NA-46 Mr. Nasir Khan P 23 NA-48 Mr. Asad Umar P 24 NA-50 Mr. Shahid Khaqan Abbasi P 25 NA-51 Raja Muhammad Javed Ikhlas P 26 NA-52 Ch. Nisar Ali Khan P 27 NA-54 Malik Ibrar Ahmed P 28 NA-55 Sheikh Rashid Ahmed P 29 NA-57 Sheikh Aftab Ahmed P 30 NA-58 Malik Itbar Khan P 31 NA-61 Sardar Mumtaz Khan P 32 NA-62 Ch. -

Sl. # Constituency Name of Member STATUS 1 NA-1 Alhaaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour P 2 NA-2 Eng

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT (Notice Office) 24th Session 1st sitting held on Monday, the 27th July, 2015 Sl. # Constituency Name of Member STATUS 1 NA-1 Alhaaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour P 2 NA-2 Eng. Hamid ul Haq Khalil P 3 NA-3 Sajid Nawaz P 4 NA-4 Gulzar Khan P 5 NA-5 Imran Khattak P 6 NA-6 Siraj Muhammad Khan P 7 NA-7 Maulana Muhammad Gohar Shah P 8 NA-8 Aftab Ahmad Khan Sherpao A 9 NA-9 Amir Haider Khan A 10 NA-10 Ali Muhammad Khan P 11 NA-11 Mujahid Ali P 12 NA-12 Engineer Usman Khan Tarakai A 13 NA-13 Aqibullah P 14 NA-14 Shehryar Afridi P 15 NA-15 Nasir Khan Khattak A 16 NA-16 Khial Zaman Orakzai A 17 NA-17 Dr. Muhammad Azhar Khan Jadoon P 18 NA-18 Murtaza Javed Abbasi P 19 NA-20 Sardar Muhammad Yousaf A 20 NA-21 Capt. Retd. Muhammad Safdar P 21 NA-22 Qari Muhammad Yousaf A 22 NA-23 Sarzameen P 23 NA-24 Maulana Fazal ur Rehman P 24 NA-25 Engineer Dawar Khan Kundi P 25 NA-26 Akram Khan Durrani A 26 NA-27 Col. Retd. Amirullah Marwat P 27 NA-28 Sher Akbar Khan P 28 NA-29 Murad Saeed P 29 NA-30 Salim Rehman P 30 NA-31 Ibadullah P 31 NA-32 Iftikhar ud Din A 32 NA-33 Sahibzada Tariq Ullah A 33 NA-34 Sahibzada Muhammad Yaqub P 34 NA-35 Junaid Akbar A 35 NA-36 Malik Bilal Rehman A 36 NA-37 Sajid Hussain Turi P 37 NA-39 Syed Ghazi Gulab Jamal P 38 NA-40 Muhammad Nazir Khan P 39 NA-41 Ghalib Khan P 40 NA-42 Muhammad Jamal ud Din P 41 NA-43 Bismillah Khan A 42 NA-44 Shahab ud Din Khan A 43 NA-45 Alhaj Shah Jee Gul Afridi P 44 NA-46 Nasir Khan P 45 NA-47 Qaisar Jamal P 46 NA-48 Asad Umar P 47 NA-49 Dr. -

KECH News July-December 2020 Edition

Tradition, Innovation, Excellence Vol. 08 No. 02 KECH NEWS July - Dec 2020 BI-ANNUAL NEWSLETTER OF UNIVERSITY OF TURBAT In this issue Important News & Events at UoT 1 PRIME MINISTER IMRAN KHAN visits UOT, ADDRESSES faculty & Students 2 PRIME MINISTER IMRAN KHAN visits UOT, ADDRESS faculty & Students (CONT) 3 5TH MEETING OF UOT’S Senate HELD, Zubaida Jalal laid THE foundation Prime Minister Imran Khan visits UoT, stone OF INSTITUTE at UOT addresses faculty and Students 4 PAIGHAM-E-Pakistan CONFERENCE HELD IN UOT Prime minister Imran Khan on 13th November, 2020 had visited 5 UOT SIGNED THE MOUS, University of Turbat and addressed to the faculty, administrative 11TH MEETING OF ACADEMIC COUNCIL staff and students of the university. He also inaugurated 6 11TH MEETING OF UOT’S FINANCE AND Planning Committee HELD, numerous development projects including “Establishment of 10TH ASRB MEETING HELD at UOT, University of Turbat Phase-ll) BRIGADIER SAQIB visits UOT 7 RCCI delegation visits UOT, Governor Balochistan Justice (R) Amanullah Khan Yasinzai, Chief BHC JUDGE, Lawyers AND Law Minister Balochistan Jam Kamal Khan Alyani, Chief Minister MAKER VISIT Law Department 8 VC inaugurates JAMEH MASJID IN UOT, Panjab Sardar Muhammad Usman Buzdar, Federal Ministers BRSDP HELD IN UOT, Zubaida Jalal, Shibli Faraz, Assad Umer, Ejaz Shah, Murad Saeed, MOU SIGNED WITH E-academy Deputy Speaker National Assembly Qasim Khan Suri, Provincial 9 ORIC HOSTED SESSION at UOT, ORIC organized WORKSHOP at UOT, ministers Mir Zahoor Ahmed Buledi, Sardar Muhammad Saleh PH.D -

Sl. # Contituency Name of Member Status 1 NA-1 Alhaaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour P 2 NA-2 Eng

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT (Notice Office) 50th Session 6th Sitting held on Thursday, the 14th December, 2017 The following Members National Assembly of Pakistan attended the sitting Sl. # Contituency Name of Member Status 1 NA-1 Alhaaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour P 2 NA-2 Eng. Hamid ul Haq Khalil P 3 NA-3 Mr. Sajid Nawaz P 4 NA-5 Dr. Imran Khattak P 5 NA-6 Mr. Siraj Muhammad Khan P 6 NA-7 Maulana Muhammad Gohar Shah P 7 NA-8 Mr. Aftab Ahmad Khan Sherpao P 8 NA-10 Mr. Ali Muhammad Khan P 9 NA-13 Mr. Aqibullah P 10 NA-14 Mr. Shehryar Afridi P 11 NA-18 Mr. Murtaza Javed Abbasi P 12 NA-22 Qari Muhammad Yousaf P 13 NA-25 Engineer Dawar Khan Kundi P 14 NA-27 Col. Retd. Amirullah Marwat P 15 NA-28 Mr. Sher Akbar Khan P 16 NA-30 Mr. Salim Rehman P 17 NA-32 Mr. Iftikhar ud Din P 18 NA-33 Sahibzada Tariq Ullah P 19 NA-35 Mr. Junaid Akbar P 20 NA-36 Mr. Bilal Rehman P 21 NA-41 Mr. Ghalib Khan P 22 NA-42 Mr. Muhammad Jamal ud Din P 23 NA-45 Alhaj Shah Jee Gul Afridi P 24 NA-46 Mr. Nasir Khan P 25 NA-47 Mr. Qaisar Jamal P 26 NA-49 Dr. Tariq Fazal Chudhary P 27 NA-51 Raja Muhammad Javed Ikhlas P 28 NA-52 Ch. Nisar Ali Khan P 29 NA-53 Mr. Ghulam Sarwar Khan P 30 NA-54 Malik Ibrar Ahmed P 31 NA-55 Sheikh Rashid Ahmed P 32 NA-57 Sheikh Aftab Ahmed P 33 NA-61 Sardar Mumtaz Khan P 34 NA-62 Ch. -

Chinese Companies Need to Explain How CPEC Will Benefit Pakistan

Chinese companies need to explain how CPEC will benefit Pakistan Mashal Khan Takkar The Voice Times (n.p) February 2, 2016 QUETTA: Chinese investors need to spell out how exactly Pakistan will benefit from the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), said political and military leaders at a seminar on Monday. They also stressed that the CPEC should not be politicised or made controversial. The matter was taken up on the second day of a seminar on peace and prosperity in Balochistan organised by the non-governmental organisation, Devote Balochistan, and the University of Balochistan in cooperation with the provincial government. Participants claimed that CPEC would be a game-changer for the country and would play an important role in the development of the province and Pakistan. They said law and order in the province had improved but more efforts should be made to ensure that this improvement was permanent. Peace, they said, would create an investment-friendly environment in the province. The seminar was attended by the Chief Minister of Balochistan, Nawab Sanaullah Zehri, federal ministers retired Gen Abdul Qadir Baloch and Jam Kamal Khan, Commander Southern Command Lt Gen Aamir Riaz, Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf’s Shafqat Mehmood and Sardar Yar Muhammad Rind, vice chancellors of the country’s leading universities, journalists and writers. Chief of Army Staff Gen Raheel Sharif, Governor Muhammad Khan Achakzai, Senator Mushahid Hussain Syed and former chief minister Dr Malik Baloch are expected to attend the seminar on Tuesday. Chief Minister Zehri said the country’s future was linked to a developed and prosperous Balochistan. -

Premiership of Mr. Shahid Khaqan Abbasi from 01

LIST OF FEDERAL MINISTERS I MINISTERS OF STATE AND ADVISERS I SPECIAL ASSISTANTS TO THE PRIME MINISTER DURING THE PREMIERSHIPOf , MR. SHAHID KHAOAN ABBASI,From 01-08-2017 to 31-05-2018. S.NO. NAME/ PERIOD PORTFOLIO PERIOD OF PORTFOLIO 04.08.2017 to 31.05.2018 2. Commerce and Textile. 04.08.2017 to 31.05.2018 3. Hafiz Abdul Kareem 04.08.2017 to 09.03.2018 04.08.2017 to 09.03.2018 Communications. 14.03.2018 to 31.05.2018 4.03.2018 to 31. Capital Administration and 4. Dr. Tariq Fazal Chaudhry 27.04.2018 to 31.05.2018 27.04.2018 Devel ment Division. 5. Engr. Khurram Dastgir Khan Defence. 04.08.2017 to 31.05.2018 04.08.20 1.0 018 Addl: Fore n Affai 201 to 31.05.2018 6. Rana Tanveer Hussain Defence Production. 04.08.2017 to 02.05.2018 04.0 Science & Techno Mr. Usman Ibrahim 7. Defence Production. 03.05.2018 to 31.05.2018 03.05.2018 Mr. Muhammad Baligh Ur 8 Federal Education and Rehman 04.08.2017 to 31.05.2018 Professional Training. 04.08.20 9. Mr. Muhammad Ishaq Dar Finance, Revenue and .08.2017 to 21.11.2017 04.08.2017 to 11.03.2018 Economic Affairs. Without Portfolio 22.11.2017 to 11.03.2018 10. Mr. Miftah Ismail Finance, Revenue and 27.04.2018 to 31.05.2018 27.04.2018 to 31.05.2018 Economic irs. 11. Khawaja Muhammad Asif Foreign Affairs. 04.08.2017 to 26.04.2018 04.08.2017 to 26. -

S.No. Contituency Name of Member Status 1 NA-2 Eng. Hamid Ul Haq Khalil P 2 NA-6 Mr

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECRETARIAT (Notice Office) 46th Session 5th Sitting held on Friday, the 15th September, 2017 The following Members National Assembly of Pakistan attended the sitting S.No. Contituency Name of Member Status 1 NA-2 Eng. Hamid ul Haq Khalil P 2 NA-6 Mr. Siraj Muhammad Khan P 3 NA-7 Maulana Muhammad Gohar Shah P 4 NA-10 Mr. Ali Muhammad Khan P 5 NA-12 Engineer Usman Khan Tarakai P 6 NA-14 Mr. Shehryar Afridi P 7 NA-15 Mr. Nasir Khan Khattak P 8 NA-17 Dr. Muhammad Azhar Khan Jadoon P 9 NA-18 Mr. Murtaza Javed Abbasi P 10 NA-23 Mr. Sarzameen P 11 NA-25 Engineer Dawar Khan Kundi P 12 NA-27 Col. Retd. Amirullah Marwat P 13 NA-28 Mr. Sher Akbar Khan P 14 NA-35 Mr. Junaid Akbar P 15 NA-43 Mr. Bismillah Khan P 16 NA-45 Alhaj Shah Jee Gul Afridi P 17 NA-48 Mr. Asad Umar P 18 NA-49 Dr. Tariq Fazal Chudhary P 19 NA-51 Raja Muhammad Javed Ikhlas P 20 NA-57 Sheikh Aftab Ahmed P 21 NA-60 Maj. Retd. Tahir Iqbal P 22 NA-61 Sardar Mumtaz Khan P 23 NA-70 Malik Shakir Bashir Awan P 24 NA-73 Mr. Abdul Majeed Khan P 25 NA-75 Lt. Col. Retd. Ghulam Rasool Sahi P 26 NA-82 Rana Muhammad Afzal Khan P 27 NA-83 Mian Abdul Manan P 28 NA-85 Haji Muhammad Akram Ansari P 29 NA-86 Mr. Qaiser Ahmad Sheikh P 30 NA-87 Mr. -

Office of Director Public Relations

PRESIDENT’S SECRETARIAT (PUBLIC) PRESS WING ----- ISLAMABAD AUGUST 04, 2017: President Mamnoon Hussain administered the oath of office to 27 Federal Ministers and 16 Ministers of State at an impressive and dignified ceremony held at the Aiwan-e-Sadr, Islamabad on Tuesday. Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbassi was also present. Those sworn in as Federal Ministers included Mohammad Ishaq Dar, Kamran Micheal, Muhammad Pervaiz Malik, Hafiz Abdul Kareem, Engr. Khurram Dastgir Khan, Syed Javed Ali Shah, Rana Tanveer Hussain, Khawaja Muhammad Asif, Akram Khan Durrani, Ghulam Murtaza Khan Jatoi, Riaz Hussain Pirzada, Ahsan Iqbal, Lt. General (R) Salahuddin Tirmizi, Muhammad Barjees Tahir, Zahid Hamid, Mushahid Ullah Khan, Sardar Awais Ahmed Khan Leghari, Pir Syed Sadaruddin Shah Rashidi, Mir Hasil Khan Bizenjo, Khawaja Saad Rafique, Sardar Muhammad Yousaf, Lt. General (Retd) Abdul Qadir Baloch, Saira Afzal Tarar, Sikandar Hayat Khan Bosan, Sheikh Aftab Ahmed, Muhammad Baligh Ur Rehman and Molana Ameer Zaman. Dr. Tariq Fazal Chaudhary, Haji Muhammad Akram Ansari, Muhammad Junaid Anwaar Chaudhry, Abid Sher Ali, Jam Kamal Khan, Marriyum Aurangzeb, Anusha Rahman, Dr. Darshan, Muhammad Tallal Chaudhry, Barrister Mohsin Shahnawaz Ranjha, Barrister Usman Ibrahim, Abdul Rehman Khan Kanju, Ch. Jaffar Iqbal, Sardar Muhammad Arshad Khan Laghari, Pir Muhammad Amin Ul Hasnat Shah and Ghalib Khan took oath as Minsters of State. Speaker National Assembly Sardar Ayaz Sadiq, parliamentarians, senior politicians, diplomats and high level civil officials attended the oath-taking ceremony. The entire oath taking ceremony was administered in national language. ********** . -

Parliamentarians Tax Directory

PARLIAMENTARIANS TAX DIRECTORY FOR YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2017 (Published on 22nd February 2019) FOREWORD Every country levies taxes to raise revenues which are essential for the running of affairs of a state and provision of public services. Development of a progressive taxation system is an essential tool to reduce social inequalities in a society and bridge the gap between the rich and the poor. The countries exhibiting due diligence in collection of taxes from the affluent segments of the society through progressive taxation and expending them judiciously for the welfare of the poor are rated high on transparency and good governance index. Efficient, fair and sustainable tax systems are critical for institution building and promoting democracy and improved economic governance. The need for transparency and accountability in a vibrant democracy imposes extra responsibility on public representatives for disclosure of their assets and the sources of their income. With these aims and objectives, Federal Board of Revenue published, its first Tax Directory of Parliamentarians in tax year 2013. However, this time, in line with the incumbent government’s reform agenda, The Directory embodies the policy of transparency and accountability through access to information. The publication of the Parliamentarians’ Tax Directory is an integral step towards ensuring transparency and informing voters about the tax- paying status of their elected representatives. Tax Directory of the honourable Parliamentarians for the tax year 2017 is now published. The directory contains tax details of members of the Senate of Pakistan and Members of the National as well as Provincial Assemblies. I would like to appreciate the efforts of the Federal Board of Revenue for compiling and publishing this tax directory.