Philip Larkin Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Irish Poetry After the Peace Process

No "Replicas/ Atone": Northern Irish Poetry After the Peace Process McConnell, G. (2018). No "Replicas/ Atone": Northern Irish Poetry After the Peace Process. Boundary 2, 45(1), 201-229. https://doi.org/10.1215/01903659-4295551 Published in: Boundary 2 Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2018 Duke University Press. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:27. Sep. 2021 1 No ‘replicas/ atone’: Northern Irish Poetry after the Peace Process Gail McConnell She’s dead set against the dead hand of Belfast’s walls guarding jinkered cul-de-sacs, siderows, bottled sloganlands, and the multinational malls’ slicker demarcations, their Xanadu of brands entwining mind and income. -

002) Fall/Winter 2013-14

This syllabus has been provided as a reference tool for students considering this course. It has been modified to follow Senate regulations. Current students enrolled in any undergraduate course must obtain the most recent syllabus from their course instructor or from their course website. This is not the latest version. Department of English & Writing Studies Twentieth-Century British and Irish Literature English 3554E (002) Fall/Winter 2013-14 Instructor: Dr. G. Donaldson Date/Time: Tuesday 2:30pm-4:10pm Thursday 2:30pm-3:20pm Location: Physics and Astronomy Building 150 Prerequisites At least 60% in 1.0 of English 1020E or 1022E or 1024E or 1035E or 1036E or both English 1027F/G and 1028F/G, or permission of the Department. Antirequisite(s): English 2331E, 2332F/G, 2333F/G, 2334E, 2335F/G and 2336F/G. Unless you have either the requisites for this course or written special permission from your Dean to enroll in it, you may be removed from this course and it will be deleted from your record. This decision may not be appealed. You will receive no adjustment to your fees in the event that you are dropped from a course for failing to have the necessary prerequisites. Course Materials Required Texts: Norton Anthology of English Literature Vol F Alan Bennett, The History Boys Angela Carter, Nights at the Circus Joseph Conrad, Under Western Eyes EM. Forster, A Passage to India Graham Swift, Waterland Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway For the poets we shall study from the Anthology, here are the poems with which to begin your reading: Thomas Hardy Hap Channel Firing The Voice Neutral Tones The Convergence of the During Wind and Rain Drummer Hodge Twain The Walk The Darkling Ah, Are You Digging on In Time of ‘The Breaking of Thrush My Grave? Nations’ A.E. -

THE NOVELS and the POETRY of PHILIP LARKIN by JOAN SHEILA MAYNE B . a . , U N I V E R S I T Y of H U L L , 1962 a THESIS SUBMITT

THE NOVELS AND THE POETRY OF PHILIP LARKIN by JOAN SHEILA MAYNE B.A., University of Hull, 1962 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M .A. in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1968 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his represen• tatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of English The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada April 26, 1968 ii THESIS ABSTRACT Philip Larkin has been considered primarily in terms of his contribution to the Movement of the Fifties; this thesis considers Larkin as an artist in his own right. His novels, Jill and A Girl in Winter, and his first volume of poetry, The North Ship, have received very little critical attention. Larkin's last two volumes of poetry, The Less Deceived and The Whitsun Weddings, have been considered as two very similar works with little or no relation to his earlier work. This thesis is an attempt to demonstrate that there is a very clear line of development running through Larkin's work, in which the novels play as important a part as the poetry. -

Rhyme, Meter, and Closure in Philip Larkin's •Œan Arundel Tomb"

Studies in English, New Series Volume 6 Article 26 1988 Rhyme, Meter, and Closure in Philip Larkin's “An Arundel Tomb" Elizabeth Gargano-Blair Iowa City Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Gargano-Blair, Elizabeth (1988) "Rhyme, Meter, and Closure in Philip Larkin's “An Arundel Tomb"," Studies in English, New Series: Vol. 6 , Article 26. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new/vol6/iss1/26 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Studies in English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English, New Series by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gargano-Blair: Rhyme, Meter, and Closure in Philip Larkin's “An Arundel Tomb" RHYME, METER, AND CLOSURE IN PHILIP LARKIN’S “AN ARUNDEL TOMB” Elizabeth Gargano-Blair Iowa City In his 1965 preface to The North Ship, Philip Larkin names three major poets who influenced his “undergraduate” and “post-Oxford” work: W. H. Auden, Dylan Thomas, and W. B. Yeats. He goes on to describe Yeats as the most potent, and potentially destructive, of these influences: “I spent the next three years trying to write like Yeats, not because I liked his personality or understood his ideas but out of infatuation with his music (to use the word I think Vernon [Watkins] used). In fairness to myself it must be admitted that it is a particularly potent music, pervasive as garlic, and has ruined many a better talent.”1 At a time when many young poets were resisting this “dangerous” music, fearful of losing poetic sense in mere sound, one challenge was to find new approaches to the use of rhyme and meter. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Different From Himself: Reading Philip Larkin After Modernism Sarah Humayun PhD English Literature University of Edinburgh 2013 ABSTRACT: This thesis addresses the work of Philip Larkin in the light of critical positions, stemming from mainly modernist perspectives, which characterize it as the opposite of what counts as innovatory, experimental and progressive in twentieth-century poetry. It aims to critique this assumption without, however, trying to prove that Larkin’s work is modernist or experimental. Rather, understanding ‘form’ in modernism as an entity that resists subjectivity and ostensibly includes otherness within its self-reflexive boundaries, it aims to offer readings of Larkin’s work that do not begin from these parameters but from an understanding of otherness as relational. Additionally, it gives extended consideration to Larkin’s prose with the aim of initiating a reconsideration of Larkin’s contribution to literature in English from a perspective that includes the essays and the novels. -

Larkin's Earlier Poetry: a Affirmation of War Circumstances Dr

Pramana Research Journal ISSN NO: 2249-2976 Larkin's Earlier Poetry: A Affirmation of War Circumstances Dr. Mohammad Arif Assistant Professor University Institute of Liberal Arts Chandigarh University [email protected] Abstract: A broad appraisal of Larkin’s work between 1938 and 1945 suggests that the poems which were selected for publication in The North Ship were those which were more cautious and withdrawn in their attitudes to the war circumstances and therefore least controversial and least polemical. The horrible circumstances of the second World War, turned Larkin into a war poet who captured the harsh realities of a time when everything seemed to fall apart. The conditions of the 1940s diverted the interest of the young Larkin to a war-affected society. Larkin felt the need of the time and made sincere attempts to brood over his country both physically and psychologically. He was deeply out of sympathy with England and his earlier work should be read in light of the poet as a “wartime refugee” who wrote about a society affected by the situation of the 1940s. Introduction Alarmed by the overwhelming nature of contemporary reality, Philip Larkin has confined himself to the erupting fallout of the post-war decline. Like other Movements poets who were concerned with tracing the “ historical and social circumstances of their time.” ( Swarbrick 71), Larkin’s poetry too, cannot be “ abstracted from the social and political history of those post-war years.” as Regan rightly observes ( PL 23). Essentially “a wry commentator” on the straitened circumstances of contemporary Britain.” (Regan 12). In fact, it might be argued that in the poetry of Philip Larkin, we not only see the image of T.S. -

At Death, You Break Up: Philip Larkin's Struggle with Mortality

Title "At death, you break up" : Philip Larkin's struggle with mortality Author(s) Harada, Keiko Citation Osaka Literary Review. 25 P.16-P.28 Issue Date 1986-12-20 Text Version publisher URL https://doi.org/10.18910/25542 DOI 10.18910/25542 rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University "At death , you break up" — Philip Larkin's struggle with mortality — Keiko Harada — "Do you think much about growing older? Is it something that worries you?" — "Yes, dreadfully. If you assume you're going to live to be seventy, seven decades, and think of each decade as a day of the week, starting with Sunday, then I'm on Friday afternoon now. Rather a shock, isn't it? If you ask why does it bother me, I can only say I dread endless extinction. 1) As if he had intended to build up his career along clear landmarks, Philip Larkin published his poetry volumes at the rate of one per decade: The North Ship in 1945, The Less Deceived in 1955, The Whitsun Weddings in 1964 and High Windows in 1974. The poet's sudden death on 2 December, 1985, at the age of sixty-three, unfortunately, left our hope for a final volume unfulfilled. Throughout these four volumes, Larkin has dedicated himself to writing about the 'unhappiness' of people caught up in time: "Deprivation is for me what daffodils were for Wordsworth"?) The recurring themes are 'memory', 'passage of time', 'old age' and 'death'. Larkin insistently dealt with them again and again. -

1. Philip Larkin

Notes References to material held in the Philip Larkin Archive lodged in the Brynmor Jones Library, University of Hull (BJL), are given as file numbers preceded by 'DPL'. 1. PHILIP LARKIN 1. Harry Chambers, 'Meeting Philip Larkin', in Larkin at Sixty, ed. Anthony Thwaite (London: Faber and Faber, 1982) p. 62. 2. John Haffenden, Viewpoints: Poets in Conversation (London, Faber and Faber, 1981) p. 127. 3. Christopher Ricks, Beckett's Dying Words (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993). 4. D. J. Enright, 'Down Cemetery Road: the Poetry of Philip Larkin', in Conspirators and Poets (London: Chatto & Windus, 1966) p. 142. 5. Hugo Roeffaers, 'Schriven tegen de Verbeelding', Streven, vol. 47 (December 1979) pp. 209-22. 6. Andrew Motion, Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life (London: Faber and Faber, 1993). 7. Philip Larkin, Required Writing (London: Faber and Faber, 1983) p. 48. 8. See Selected Letters of Philip Larkin 1940-1985, ed. Anthony Thwaite (London: Faber and Faber, 1992) pp. 648-9. 9. DPL 2 (in BJL). 10. DPL 5 (in BJL). 11. Kingsley Amis, Memoirs (London: Hutchinson, 1991) p. 52. 12. Philip Larkin, Introduction to Jill (London: The Fortune Press, 1946; rev. edn. Faber and Faber, 1975) p. 12. 13. Donald Davie, Thomas Hardy and British Poetry (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973) p. 64. 14. Required Writing, p. 297. 15. Blake Morrison, 'In the grip of darkness', The Times Literary Supplement, 14-20 October 1988, p. 1152. 16. Lisa Jardine, 'Saxon violence', Guardian, 8 December 1992. 17. Bryan Appleyard, 'The dreary laureate of our provincialism', Independent, 18 March 1993. 18. Ian Hamilton, 'Self's the man', The Times Literary Supplement, 2 April 1993, p. -

We Met at the End of the Party’

APPENDIX: ‘Be my Valentine this Monday’ and ‘We met at the end of the party’ These poems came to light in 2002, as a result of a complicated sequence of events. Following Monica Jones’s death on 15 February 2001, the staff of the Brynmor Jones Library, Hull, cleared 105 Newland Avenue of Larkin’s remaining books and manuscripts. The Philip Larkin Society then purchased the remaining non-literary items: furniture, pictures and ornaments. These were removed in late 2001 and early 2002, and are now on long-term loan to the Hull Museums Service and the East Riding Museum Service. Both searches missed a small dark red ‘©ollins Ideal 468’ hard-backed manu- script notebook which had slipped behind the drawers of a bedside cabinet. This cabinet was removed by the house-clearer with the final debris, and subse- quently fell into the hands of a local man, Chris Jackson, who contacted the Larkin Society. I confirmed the authenticity of the book in a brief meeting with Mr Jackson in the Goose and Granite public house in Hull on 17.vii.2002. The notebook seems initially to have been intended for ‘Required Writing’, which Larkin wished to keep separate from the drafts in his workbooks proper. The first eleven sides are occupied by pencil drafts of ‘Bridge for the Living’, dated between 30 May 1975 and 27 July 1975. These are followed by notes on Thomas Hardy and other topics. Seven months later, however, Larkin used the book again, this time for more personal writing. The central pages were left blank but on the final five sides he wrote pencil drafts, dated between 7 February 1976 and 21 February 1976, of ‘Morning at last: there in the snow’, ‘Be my Valentine this Monday’ and ‘We met at the end of the party’. -

Book REVIEW S

BooK REVIEW S Holy Days of Obligation. By Susan Zettell. Winnipeg: Nuage Edi tions, 1998. 160 pages. $14.95 paper. Given a tomato still warm out of the garden, you instinctively bring it to your nose and take a deep breath. The essence of fresh tomato, the memo1y of eve1y perfect tomato eaten, the smell of summer. In Ho~y Days of Obligation, Susan Zettell brings memory to instant life with writing that connects to all the senses. The fift een stories in Holy Days of Obligation move forward and back in time. as mem01y makes one connection, then another in a family histo1y: the after-rain smell of worms in the backyard brings back a fishing trip; the steaming wool of ironed trousers evokes the winter mem01y of nine pairs of sodden mittens drying over the furnace vents. And the perfect tomato sand wich is insisted on by a dying man who won't give up the memory of appe tite. Bertie is the oldest child, big sister, responsible for helping with eight younger siblings. Nine children- the pattern of names sung into the suppertime dusk: ·'Bertie-Catherine-Margaret-Robert-David-Ronnie-Michael-Sancly-Simon." The siblings appear here and there in Zettell's stories as distinct personalities, but more often as part of a sticky. noisy, earful or houseful of too many bodies. Frank and Elizabeth are always "our father," "our mother," never just Bertie·s. The young Bertie watches and remembers. if she doesn't always understand at the time: "I feel as if I'm more eyes and ears than anything else . -

W. H. Auden and Me

W. H. Auden and me 125 (`Edward', `The Twa Corbies'), `The Rime of the Ancient Mariner', `The 5 Journey of the Magi', and Auden's `O what is that sound?', simply called `Ballad' here.' The last came, somehow, with the absolute certainty of knowledge that the point of poetry was its ambiguity; that you just couldn't W. H. Auden and me know what it meant. This I must have been taught, though possibly not in that particular classroom. Is it a man or woman who speaks? Who, in answer to the question about the sound of drumming coming closer from down in the valley, says: `Only the scarlet soldiers, dear,/The soldiers coming.'? Who has betrayed whom? Who cries out `O where are you going? Stay with me here!/ Were the vows you swore deceiving, deceiving?'? Who replies: `No, I promised to love you, dear,/But I must be leaving'? These questions were discussed; we knew that there wasn't an answer to any of ... we go back them; that indeterminacy was the point of asking them. We wouldn't have to `Consider this and in our time'; put it like that. We were 15 years old. But we — probably — played about it's a key text, no doubt about it: with the questions after class, just as a year later under the influence of our A-level French set-texts we devised a wet the first garden party of the year, -your-knickers comic routine in the leisurely conversation in the bar, which the romantic poets Hugo and de Musser (`Huggo and Mussett') the fact that it is later were a seedy, down-at-heel music hall duo, doomed to play the Bingley than we think. -

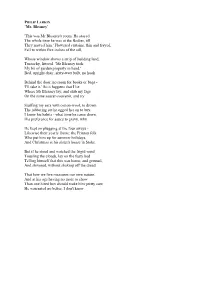

PHILIP LARKIN ’Mr

PHILIP LARKIN ’Mr. Bleaney’ 'This was Mr Bleaney's room. He stayed The whole time he was at the Bodies, till They moved him.' Flowered curtains, thin and frayed, Fall to within five inches of the sill, Whose window shows a strip of building land, Tussocky, littered. 'Mr Bleaney took My bit of garden properly in hand.' Bed, upright chair, sixty-watt bulb, no hook Behind the door, no room for books or bags - 'I'll take it.' So it happens that I lie Where Mr Bleaney lay, and stub my fags On the same saucer-souvenir, and try Stuffing my ears with cotton-wool, to drown The jabbering set he egged her on to buy. I know his habits - what time he came down, His preference for sauce to gravy, why He kept on plugging at the four aways - Likewise their yearly frame: the Frinton folk Who put him up for summer holidays, And Christmas at his sister's house in Stoke. But if he stood and watched the frigid wind Tousling the clouds, lay on the fusty bed Telling himself that this was home, and grinned, And shivered, without shaking off the dread That how we live measures our own nature, And at his age having no more to show Than one hired box should make him pretty sure He warranted no better, I don't know. ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ That Whitsun, I was late getting away: Not till about One-twenty on the sunlit Saturday Did my three-quarters-empty train pull out, All windows down, all cushions hot, all sense Of being in a hurry gone.