Matthew Parkes the Geological Heritage of Fingal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

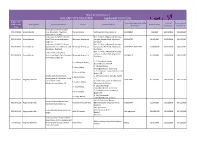

Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to Be Crossed by the Proposed Project

Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to be Crossed by the Proposed Project TB No.: 1 Townlands: Abbotstown/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309268, 238784 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection TB No.: 2 Townlands: Dunsink/ Sheephill Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309327, 238835 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House (within the townland of Sheephill) and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). The remains of a stone demesne wall associated with Abbotstown are located along the northern side of the road (UBH 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection 32102902/EIAR/3B Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 TB No.: 3 Townlands: Sheephill/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 310153, 239339 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south. -

Hydrogeology of the Burren and Gort Lowlands

KARST HYDROGEOLOGY OF THE BURREN UPLANDS / GORT LOWLANDS Field Guide International Association of Hydrogeologists (IAH) Irish Group 2019 Cover page: View north across Corkscrew Hill, between Lisdoonvarna and Ballyvaughan, one of the iconic Burren vistas. Contributors and Excursion Leaders. Colin Bunce Burren and Cliffs of Moher UNESCO Global Geopark David Drew Department of Geography, Trinity College, Dublin Léa Duran Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Laurence Gill Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Bruce Misstear Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin John Paul Moore Fault Analysis Group, Department of Geology, University College Dublin and iCRAG Patrick Morrissey Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin and Roughan O‘Donovan Consulting Engineers David O’Connell Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Philip Schuler Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin Luka Vucinic Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, Trinity College, Dublin and iCRAG Programme th Saturday 19 October 10.00 Doolin Walk north of Doolin, taking in the coast, as well as the Aillwee, Balliny and Fahee North Members, wayboards, chert beds, heterogeneity in limestones, joints and veins, inception horizons, and epikarst David Drew and Colin Bunce, with input from John Paul Moore 13.00 Lunch in McDermotts Bar, Doolin 14.20 Murrooghtoohy Veins and calcite, relationship to caves, groundwater flow and topography John Paul Moore 15.45 Gleninsheen and Poll Insheen Holy Wells, epikarst and hydrochemistry at Poll Insheen Bruce Misstear 17.00 Lisdoonvarna Spa Wells Lisdoonvarna history, the spa wells themselves, well geology, hydrogeology and hydrochemistry, some mysterious heat .. -

Waste Water Discharge Licence Application for Portrane Donabate

Waste Water Discharge Licence Application for Portrane Donabate Rush Lusk Agglomeration. Attachment F1: Assessment of Impact. For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. EPA Export 29-09-2011:04:17:42 Fingal County Council For inspection purposes only. Portrane DonabateConsent of copyright Rush owner required Lusk for any other Waste use. Water Discharge Licence Application Appropriate Assessment Aug 2011 EPA Export 29-09-2011:04:17:42 Portrane Donabate Rush Lusk Waste Water Discharge Licence Application – Appropriate Assessment Contents 1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................3 2 SCREENING ........................................................................................................................2 2.1 MANAGEMENT OF THE SITE ......................................................................................2 2.2 DESCRIPTION OF PLAN OR PROJECT..........................................................................2 2.3 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SITE................................................................................4 2.4 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ..............................................................................11 For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. EPA Export 29-09-2011:04:17:42 Portrane Donabate Rush Lusk Waste Water Discharge Licence Application – Appropriate Assessment 1 INTRODUCTION Fingal County Council is submitting -

Establishment of Groundwater Source Protection Zones Martinstown

Establishment of Groundwater Source Protection Zones Martinstown, Ballinvreena Water Supply Scheme December 2010 Prepared by: OCM With contributions from: Dr. Robert Meehan, Ms. Jenny Deakin, Mr. David Ball And with assistance from: Limerick County Council l v Environmental Protection Agency Martinstown Ballinvreena Groundwater SPZ Project description Since the 1980’s, the Geological Survey of Ireland (GSI) has undertaken a considerable amount of work developing Groundwater Protection Schemes throughout the country. Groundwater Source Protection Zones are the surface and subsurface areas surrounding a groundwater source, i.e. a well, wellfield or spring, in which water and contaminants may enter groundwater and move towards the source. Knowledge of where the water is coming from is critical when trying to interpret water quality data at the groundwater source. The Source Protection Zone also provides an area in which to focus further investigation and is an area where protective measures can be introduced to maintain or improve the quality of groundwater. The project “Establishment of Groundwater Source Protection Zones”, led by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), represents a continuation of the GSI’s work. A CDM/TOBIN/OCM project team has been retained by the EPA to establish Groundwater Source Protection Zones at monitoring points in the EPA’s National Groundwater Quality Network. A suite of maps and digital GIS layers accompany this report and the reports and maps are hosted on the EPA and GSI websites (www.epa.ie; www.gsi.ie). i Environmental Protection Agency Martinstown Ballinvreena Groundwater SPZ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 2 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 1 3 Location, Site Description and Well Head Protection .......................................... -

Fingal County Council

Development Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 County / City Council GIS X GIS Y Ballalease Court Portrane Road Donabate Fingal Belmayne Phase 3 Belmayne Clongriffin Fingal Belmayne Phase 4 Belmayne Clongriffin Fingal Bremore Lodge Hamlet lane Balbriggan Fingal Bremore Pastures Bremore Balbriggan Fingal Casleland Rise Castleland Balbriggan Fingal Castlegrange Hansfield Fingal Castleland Park Castleland Balbriggan Fingal Castlemoyne Phase2 Balgriffin Pk House Balgriffin, D17 Fingal Charlestown St Margarets Rd Finglas Fingal Courtneys Way Garristown Village Garristown Fingal Creston Park St Margarets Rd Finglas Fingal Delvin Banks Balbriggan Road Naul Fingal Golden Ridge Skerries Road Rush Fingal Hampton Gardens Naul Road Balbriggan Fingal Hastings Lawn Bremore Balbriggan Fingal Hayestown Close Old Hayestown Rush Fingal Heathfield Cappagh Finglas Fingal Knocksedan Naul road Brackenstown Fingal Lynwood Ballyboughal Village Ballyboughal Fingal Mayeston Hall St Margarets Finglas, D11 Fingal Mill Hill Park Mill Hill Skerries Fingal Murragh House Murragh Oldtown Fingal Oldtown Avenue Fieldstown road Oldtown Fingal Plan Ref F02A/0358 (Windmill) Porterstown Clonsilla Fingal 706393 737838 Plan Ref F03A/1640 Drinan Kinsealy Fingal 719333 745053 Plan Ref F04A/1584 Cruise Park Tyrrelstown Fingal 706636 742278 Plan Ref F04A/1655 Phoenix Park Ashtown Fingal 710470 737140 Plan Ref F05A/0265 (Ridgewood — Phase 7A) Forest Road Swords Fingal 716660 745332 Plan Ref F06A/0671 (Stapolin Phase 3) Stapolin Baldoyle Fingal 723269 740731 Plan Ref F06A/0903 Carrickhill -

Ecological Study of the Coastal Habitats in County Fingal Habitats Phase I & II Flora

Ecological Study of the Coastal Habitats in County Fingal Habitats Phase I & II Flora Fingal County Council November 2004 Supported by Ecological Study of the Coastal Habitats in County Fingal Phase I & II Habitats & Flora Prepared by: Dr. D. Doogue, Ecological Consultant D. Tiernan, Fingal County Council, Parks Division H. Visser, Fingal County Council, Parks Division November 2004 Supported by Michael A. Lynch, Senior Parks Superintendent. Table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Objectives 2 1.2 The Study Area 3 1.3 Acknowledgements 4 2. METHODOLOGY 2.1 The Habitat Mapping 6 2.2 The Vegetation Survey 6 2.3 The Rare Plant Survey 6 3 RESULTS 3.1 Habitat Classes 8 3.1.1 The Coastland 8 3.1.1.1 Rocky Sea Cliffs 8 3.1.2.2 Sea stacks and islets 9 3.1.1.3 Sedimentary sea cliffs 9 3.1.1.4 Shingle and Gravel banks 10 3.1.1.5 Embryonic dunes 10 3.1.1.6 Marram dunes 11 3.1.1.7 Fixed dunes 11 3.1.1.8 Dune scrub and woodland 12 3.1.1.9 Dune slacks 12 3.1.1.10 Coastal Constructions 12 3.1.2 Estuaries 12 3.1.2.1 Mud shores 13 3.1.2.2 Lower saltmarsh 13 3.1.2.3 Upper saltmarsh 14 3.1.3 Seashore 15 3.1.3.1 Sediment shores 15 3.1.3.2 Rocky seashores 15 3.2 Habitat Maps & Site Reports 16 3.2.1 Delvin 17 3.2.2 Cardy Point 19 3.2.3 Balbriggan 21 3.2.4 Isaac’s Bower 23 3.2.5 Hampton 26 3.2.6 Skerries – Barnageeragh 28 3.2.7 Red Island 31 3.2.8 Skerries Shore 31 3.2.9 Loughshinny 33 3.2.10 North Rush to Loughshinny 37 3.2.11 Rush Sandhills 38 3.2.12 Rogerstown Shore 41 3.2.13 Portrane Burrow 43 3.2.14 Corballis 46 3.2.15 Portmarnock 49 3.2.16 The Howth Peninsula 56 4. -

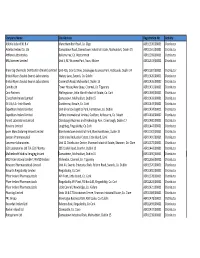

VACANT SITE REGISTER (Updated 10/01/20) Register No

Fingal County Council VACANT SITE REGISTER (updated 10/01/20) Register No. Property Ownership Folio Date of Date entered (Link to Site Description Property Address Owner Owner Address Market Value Reference Valuation on Register Map) Flemington Park / Flemington FCC VS/0009 Greenfield site Lane, Flemington Townland, Pauline Murphy 23 Fitzwilliam Place, Dublin 2 DN178996F €480,000 31/05/2018 28/12/2017 Balbriggan, Co Dublin. Lands west of the R121 Church Unit 11, Block F, Maynooth Business FCC VS/0016 Greenfield site Road, Townland of Hollystown, Glenveagh Homes Ltd Campus, Straffan Road, Maynooth, DN209979F €5,000,000 23/05/2018 28/12/2017 Dublin 15 Co.Kildare Lands west of the R121 Church Unit 11, Block F, Maynooth Business FCC VS/0017 Greenfield site Road, Townlands of Kilmartin and Glenveagh Homes Ltd Campus, Straffan Road, Maynooth, DN215479F, DN31149F €13,000,000 23/05/2018 28/12/2017 Hollystown, Dublin 15 Co.Kildare Unit 11, Block F, Maynooth Business Lands to the northwest of Campus, Straffan Road, Maynooth, FCC VS/0018 Greenfield site Tyrrelstown Public Park, Townland Glenveagh Homes Ltd DN168811F €1,200,000 23/05/2018 28/12/2017 Co.Kildare of Kilmartin, Dublin 15 1- 11 Woodlands Manor, 1- Linda Byrne Molloy, Ratoath, County Meath 2- 12a Castleknock 2- Mary Molloy, Green, Castleknock, Dublin 15 3- 12 Somerton, Castleknock Golf Club, 3- Patrick Molloy, Dublin 15 Directly east of Ulster Bank, 4- 23 The Courtyard, Clonsilla, Dublin 4- Susan Molloy, forming part of Deanstown House 15 FCC VS/0117 Regeneration Site DN217018F €1,200,000 18/11/2019 08/11/2019 Site on Main Street, 5- Toolestown House, Straffan Road, 5- Stephen Molloy, Blanchardstown, Dublin 15 Maynooth, Co. -

PDF (Full Report)

A Collective Response Philip Jennings 2013 Contents Acknowledgements…………………………....2 Chairperson’s note…………………………….3 Foreword……………………………………...4 Melting the Iceberg of Intimidation…………...5 Understanding the Issue………………………8 Lower Order…………………………………10 Middle Order………………………………...16 Higher Order………………………………...20 Invest to Save………………………………..22 Conclusion…………………………………..24 Board Membership…………………………..25 Recommendations…………………………...26 Bibliography………………………………....27 1 Acknowledgements: The Management Committee of Safer Blanchardstown would like to extend a very sincere thanks to all those who took part in the construction of this research report. Particular thanks to the staff from the following organisations without whose full participation at the interview stage this report would not have been possible; Mulhuddart Community Youth Project (MCYP); Ladyswell National School; Mulhuddart/Corduff Community Drug Team (M/CCDT); Local G.P; Blanchardstown Local Drugs Task Force, Family Support Network; HSE Wellview Family Resource Centre; Blanchardstown Garda Drugs Unit; Local Community Development Project (LCDP); Public Health Nurse’s and Primary Care Team Social Workers. Special thanks to Breffni O'Rourke, Coordinator Fingal RAPID; Louise McCulloch Interagency/Policy Support Worker, Blanchardstown Local Drugs Task Force; Philip Keegan, Coordinator Greater Blanchardstown Response to Drugs; Barbara McDonough, Social Work Team Leader HSE, Desmond O’Sullivan, Manager Jigsaw Dublin 15 and Sarah O’Gorman South Dublin County Council for their editorial comments and supports in the course of writing this report. 2 Chairpersons note In response to the research findings in An Overview of Community Safety in Blanchardstown Rapid Areas (2010) and to continued reports of drug debt intimidation from a range of partners, Safer Blanchardtown’s own public meetings and from other sources, the management committee of Safer Blanchardstown decided that this was an issue that required investigation. -

Fingal Historic Graveyards Project Volume 1

Fingal Historic Graveyards Project Volume 1 Introduction 1. Introduction..................................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Acknowledgments.................................................................................................. 2 2. Fingal Historic Graveyard Project................................................................................. 2 2.1. Survey Format ........................................................................................................ 2 2.1.1. Graveyard Survey Form................................................................................ 2 2.1.2. Site Information ............................................................................................. 3 2.1.3. General Information ...................................................................................... 3 2.1.4. Location.......................................................................................................... 3 2.1.5. Designations .................................................................................................. 3 2.1.6. Historic Maps ................................................................................................. 9 2.1.7. Setting............................................................................................................. 9 2.1.8. Historical Context.......................................................................................... 9 2.1.9. Bibliographic References ............................................................................ -

Seamount Abbey Across Dublin City and Residential Location, Train Station, 5 Km from the M1 2.54 Ha (6.27 Acre) and Detached Houses; 11 No

SEA MOUNT MALAHIDE | CO DUBLIN SEA MOUNT Highly Exclusive Development Opportunity with Full Planning Permission for 46 Luxury Houses | Approx. 3.34 ha (8.25 acre) SEA MOUNT BER Exempt SEA MOUNT MALAHIDE | CO DUBLIN ASSET HIGHLIGHTS SEA MOUNT SEA MOUNT Balbriggan Superb development The larger site has full Skerries Potential for Adjacent to Elevated setting Exceptionally Highly accessible location, opportunity comprising planningM1 permission for additional residential highly successful with stunning views high quality approx. 1 km from Malahide two sites of approx. development of 46 large development on the Seamount Abbey across Dublin city and residential location, Train Station, 5 km from the M1 2.54 ha (6.27 acre) and detached houses; 11 no. second site development Malahide Estuary less than 1 km from motorway, 8 km from Dublin 0.80 ha (1.98 acre) 3 bedroom houses and Malahide Castle Airport, 9 km from the M50 Ballyboghil Lusk Ashbourne 35 no. 4 bedroom houses motorway and 14 km from Dublin city centre Donabate Swords M1 MALAHIDE MALAHIDE DUBLIN St. Margarets AIRPORT Kinsealy Portmarnock Malahide is a highly desirable coastal town, situated Malahide is well accessible by public transport, with R107 R106 approx. 14 km north of Dublin city centre. As at Census Malahide Train Station providing regular services R132 2016, Malahide had a population of 23,681. Malahide is to Dublin city. Various Dublin Bus routes also serve M50 Balgriffin renowned for its enviable array of amenities. Malahide the location. This coastal setting also offers a host of Finglas Sutton village offers extensive retail facilities and services seaside attractions, including Malahide Beach, Malahide Whitehall Donaghmede Howth including fashion boutiques, hair and beauty salons, Marina and Malahide Yacht Club. -

Company Name Site Address Registration No

Company Name Site Address Registration No. Activity AbbVie Ireland NL B.V Manorhamilton Road, Co. Sligo ASR11336/00001 Distributor Astellas Ireland Co. Ltd Damastown Road, Damastown Industrial Estate, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11341/00001 Distributor Athlone Laboratories Ballymurray, Co. Roscommon ASR11399/00001 Distributor BNL Sciences Limited Unit S, M7 Business Park, Naas, Kildare ASR11343/00001 Distributor Brenntag Chemicals Distribution (Ireland) Limited Unit 405, Grants Drive, Greenogue Business Park, Rathcoole, Dublin 24 ASR11387/00001 Distributor Bristol‐Myers Squibb Swords Laboratories Watery Lane, Swords, Co. Dublin ASR11426/00001 Distributor Bristol‐Myers Squibb Swords Laboratories Cruiserath Road, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11426/00002 Distributor Camida Ltd Tower House, New Quay, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary ASR11431/00001 Distributor Cara Partners Wallingstown, Little Island Industrial Estate, Co. Cork ASR11494/00001 Distributor Clarochem Ireland Limited Damastown, Mulhuddart, Dublin 15 ASR11433/00001 Distributor Eli Lilly S.A ‐ Irish Branch Dunderrow, Kinsale, Co. Cork ASR11449/00001 Distributor Expeditors Ireland Limited Unit 6 Horizon Logistics Park, Harristown, Co. Dublin ASR11434/00001 Distributor Expeditors Ireland Limited Caffery International Limited, Coolfore, Ashbourne, Co. Meath ASR11434/00002 Distributor Forest Laboratories Limited Clonshaugh Business and Technology Park. Clonshaugh, Dublin 17 ASR11400/00001 Distributor Hovione Limited Loughbeg, Ringaskiddy, Co.Cork ASR11447/00001 Distributor Ipsen Manufacturing Ireland -

Whitechurch Stream Flood Alleviation Scheme

WHITECHURCH STREAM FLOOD ALLEVIATION SCHEME Environmental Report MDW0825 Environmental Report F01 06 Jul. 20 rpsgroup.com WHITECHURCH STREAM FAS-ER Document status Version Purpose of document Authored by Reviewed by Approved by Review date A01 For Approval HC PC MD 09/04/20 A02 For Approval HC PC MD 02/06/20 F01 For Issue HC PC MD 06/07/20 Approval for issue Mesfin Desta 6 July 2020 © Copyright RPS Group Limited. All rights reserved. The report has been prepared for the exclusive use of our client and unless otherwise agreed in writing by RPS Group Limited no other party may use, make use of or rely on the contents of this report. The report has been compiled using the resources agreed with the client and in accordance with the scope of work agreed with the client. No liability is accepted by RPS Group Limited for any use of this report, other than the purpose for which it was prepared. RPS Group Limited accepts no responsibility for any documents or information supplied to RPS Group Limited by others and no legal liability arising from the use by others of opinions or data contained in this report. It is expressly stated that no independent verification of any documents or information supplied by others has been made. RPS Group Limited has used reasonable skill, care and diligence in compiling this report and no warranty is provided as to the report’s accuracy. No part of this report may be copied or reproduced, by any means, without the written permission of RPS Group Limited.