Bach Violin Concertos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Recording Booklet

Johann Sebastian Bach EDITION: BREITKOPF & HÄRTEL, EDITED BY J. RIFKIN (2006) Dunedin Consort & Players John Butt director SUSAN HAMILTON soprano CECILIA OSMOND soprano MARGOT OITZINGER alto THOMAS HOBBS tenor MATTHEW BROOK bass MASS IN J S Bach (1685-1750) Mass in B minor BWV 232 B MINOR Mass in B minor Edition: Breitkopf & Härtel, edited by Joshua Rifkin (2006) Johann Sebastian Bach Dunedin Consort & Players John Butt director ach’s Mass in B Minor is undoubtedly his most spectacular choral work. BIts combination of sizzling choruses and solo numbers covering the gamut of late-Baroque vocal expression render it one of the most joyous musical 6 Et resurrexit ............................................................... 4.02 Missa (Kyrie & Gloria) experiences in the western tradition. Nevertheless, its identity is teased by 7 Et in Spiritum sanctum ................................. 5.27 countless contradictions: it appears to cover the entire Ordinary of the Catholic 1 Kyrie eleison .............................................................. 9.39 8 Confiteor ....................................................................... 3.40 Liturgy, but in Bach’s Lutheran environment the complete Latin text was seldom 2 Christe eleison ........................................................ 4.33 9 Et expecto .................................................................... 2.07 sung as a whole; it seems to have the characteristics of a unified work, yet its 3 Kyrie eleison ............................................................. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 2 Tuomo Suni, Violin Tuomo 3

1 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 2 Tuomo Suni, violin Tuomo 3 MISSION STATEMENT To move, engage, challenge and delight our audiences through our music with performances, recordings and educational activities, both in Scotland and beyond. VISION To be recognised as one of the leading international ensembles in period performance, admired for our particularly lively engagement with historical discovery and spontaneous music making, creative programming, and the infectious commitment of our world-class musicians, audiences and supporters, both in Scotland and in the international arena. CORE VALUES Caring for and nurturing our audience, supporters, musicians and employees, bringing them ever closer to the centre of our work. Performing programmes that our musicians and audiences find engaging, challenging and rewarding, bringing our music to as many people of the diverse communities we serve as possible. Exploring fully the potential of our historical heritage to bring to the fore connections with our present and stress the vitality and relevance of our work. Fostering in our musicians the inquisitive, searching, experimenting mindset necessary to ensure our music remains vibrant and relevant. We believe everyone has the right to enjoy our music and we are committed to ensuring non-professional singers and instrumentalists of all ages, as well as the next generation of professional musicians and scholars have the opportunity to engage with and learn from our work in a deep and meaningful way. 4 Recording Handel’s Samson at St Jude’s on the Hill, London, May 2018 Samson at St Jude’s Recording Handel’s 5 CONTENTS MUSIC DIRECTOR’S REPORT 6 CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S REPORT 7 TRUSTEES’ REPORT 8 ACHIEVEMENTS AND PERFORMANCE 12 FINANCIAL REVIEW 18 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 22 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 28 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT 38 6 MUSIC DIRECTOR’S REPORT At the beginning of the new financial year, we found The latter was described by The Times as ‘ensemble ourselves in Krakow, undertaking one of Dunedin brilliance at its most inventive and scintillating’. -

Historically Informed Performance

Impact case study (REF3b) Institution: University of Glasgow Unit of Assessment: 35 – Music Title of case study: Original performances of Bach and Handel recreated for global contemporary audiences 1. Summary of the impact John Butt’s research has played a leading role in bringing historically informed music performance to professional and public audiences across the world. His recording of Messiah (2006) achieved critical acclaim and was presented with the Classic FM/Gramophone Baroque Vocal Album and the Marché International du Disque et de l'Edition Musicale Award. The recording also achieved commercial success for independent record producer, Linn Records with sales of over 20,000, and had a significant impact on Scotland’s leading baroque ensemble, the Dunedin Consort, with seven more recordings of works by Bach and Handel, substantial royalty income, increased funding (including new subsidies) and new touring opportunities. This success has also enabled an active education outreach programme to develop both professional training and broader public interest. 2. Underpinning research Intellectual background In 2002 John Butt (University of Glasgow Gardiner Chair of Music, 2001-present) published a major monograph on the culture of historically informed performance. Playing with History (Cambridge University Press) established many of the primary questions regarding the role of historically informed performance in contemporary culture – such as how it ties into other historical conditions and its potential to refresh many aspects of classical music culture. One of the most significant conclusions was identifying the need to use historical knowledge and experience to encourage new creative possibilities in contemporary performance, even if adopting historical parameters might suggest a restriction of performative possibilities. -

2016-2017 Season

1 Emily Mitchell (Soprano) 2 MONTEVERDI Vespers 1610 Monteverdi’s spectacular masterpiece of 1610 is the most lavish of all the music that this peerless genius wrote for the church in early 17th century Venice. Nothing composed before Bach can rival it for sonic grandeur, but there is intimacy too in Monteverdi’s brilliantly imaginative use of solo voices and instruments. With a starry vocal line-up, joined by the virtuoso players of Dunedin Consort and His Majestys Sagbutts and Cornetts, join us for what promises to be an unmissable event. Monteverdi Fri 09.09.2016 Vespro della beata Vergine, 1610 Lammermuir Festival, St Mary’s Haddington Director John Butt 7.30pm | £19.50 – £11.50 Soprano Sold out. Returns only Joanne Lunn Esther Brazil Soprano Emilie Renard Mezzo Sun 11.09.2016 Joshua Ellicott Tenor Perth Concert Hall Matthew Long Tenor Bass 3pm | £19.50 – £11.50 Edward Grint Matthew Brook Bass with His Majesties Sackbutts and Cornetts 3 Christine Sticher (Double Bass) 4 PURCELL, SHAKESPEARE & CERVANTES Fantasy & Madness From a world in which windmills are giants and ordinary inns are castles, through the underwater kingdom of Neptune & Amphitrite, to an enchanted forest filled with fairies, the stories of Cervantes and Shakespeare are lifted off the page by Purcell’s theatrically rich musical settings. The Elizabethan literary landscapes of Don Quixote de la Mancha, The Tempest, and A Midsummer’s Night Dream are staged fusing sound, light, costume, and the beauty of the written word. Inspired by the theatrical spectacle and machinery, which lies at the heart of Restoration period theatre and opera, two singers embody the stories of these writers through voice and action, as they continually uncover moments of transformation within their costume. -

DUNEDIN CONSORT JOHN BUTT SIX Brandenburg Concertos

DUNEDIN CONSORT JOHN BUTT SIX BRANDENBURG CONCERTOS John Butt Director and Harpsichord Cecilia Bernardini Violin Pamela Thorby Recorder David Blackadder Trumpet Alexandra Bellamy Oboe Catherine Latham Recorder Katy Bircher Flute Jane Rogers Viola Alfonso Leal del Ojo Viola Jonathan Manson Violoncello Recorded at Post-production by Perth Concert Hall, Perth, UK Julia Thomas from 7-10 May 2012 Design by Produced and recorded by Gareth Jones and gmtoucari.com Philip Hobbs Photographs by Assistant engineering by David Barbour Robert Cammidge Cover image: The Kermesse, c.1635-38 (oil on panel) by Peter Paul Rubens (Louvre, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library) DISC 1 Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F Major, BWV 1046 Concerto 1mo à 2 Corni di Caccia, 3 Hautb: è Bassono, Violino Piccolo concertato, 2 Violini, una Viola è Violoncello col Basso Continuo q […] 4:02 w Adagio 3:44 e Allegro 4:11 r Menuet Trio Polonaise 8:47 Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F Major, BWV 1047 Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino, concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo t […] 4:51 y Andante 3:18 u Allegro assai 2:44 Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G Major, BWV 1048 Concerto 3zo a tre Violini, tre Viole, è tre Violoncelli col Basso per il Cembalo i […] 5:30 o Adagio 0:25 a Allegro 4:46 Total Time: 42:44 DISC 2 Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G Major, BWV 1049 Concerto 4ta à Violino Principale, due Fiauti d’Echo, due Violini, una Viola è Violone in Ripieno, Violoncello è Continuo q Allegro 6:45 w Andante 3:20 e Presto 4:30 Brandenburg Concerto No. -

J.S. Bach Das Wohltemperierte Klavier

.S. ach J Bas wohltemperierteD lavier K John Butt Johann Sebastian Bach as wohltemperierte lavier John Butt harpsichord D K The Well-Tempered Clavier Book I, BWV 846–69 isc 1 isc 2 1.D Prelude No. 1 in C major ...................2:00 1.D Prelude No. 13 in F sharp major ........ 1:24 2. Fugue No. 1 in C major ......................1:31 2. Fugue No. 13 in F sharp major ........... 1:33 3. Prelude No. 2 in C minor .................. 1:26 3. Prelude No. 14 in F sharp minor .........1:19 4. Fugue No. 2 in C minor ..................... 1:20 4. Fugue No. 14 in F sharp minor ........... 1:52 5. Prelude No. 3 in C sharp major ....... 1:20 5. Prelude No. 15 in G major ..................0:52 6. Fugue No. 3 in C sharp major .......... 2:16 6. Fugue No. 15 in G major.....................2:38 7. Prelude No. 4 in C sharp minor ....... 1:53 7. Prelude No. 16 in G minor .................. 1:09 8. Fugue No. 4 in C sharp minor ..........2:45 8. Fugue No. 16 in G minor..................... 1:32 9. Prelude No. 5 in D major ................... 1:11 9. Prelude No. 17 in A flat major .............. 1:22 10. Fugue No. 5 in D major ..................... 1:34 10. Fugue No. 17 in A flat major ............... 1:56 11. Prelude No. 6 in D minor .................. 1:20 11. Prelude No. 18 in G sharp minor .........1:13 12. Fugue No. 6 in D minor ..................... 1:46 12. Fugue No. 18 in G sharp minor ........ -

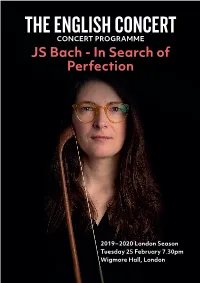

EC-Bach Perfection Programme-Draft.Indd

THE ENGLISH CONCE∏T 1 CONCERT PROGRAMME JS Bach - In Search of Perfection 2019 – 2020 London Season Tuesday 25 February 7.30pm Wigmore Hall, London 2 3 WELCOME PROGRAMME Wigmore Hall, More than any composer in history, Bach The English Concert 36 Wigmore Street, Orchestral Suite No 4 in D Johann Sebastian Bach is renowned Laurence Cummings London, W1U 2BP BWV 1069 Director: John Gilhooly for having frequently returned to his Guest Director / The Wigmore Hall Trust own music. Repurposing and revising it Bach Harpsichord Registered Charity for new performance contexts, he was Sinfonia to Cantata 35: No. 1024838. Lisa Beznosiuk Geist und Seele wird verwirret www.wigmore-hall.org.uk apparently unable to help himself from Flute Disabled Access making changes and refinements at Bach and Facilities Tabea Debus Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D every level. Recorder BWV 1050 Tom Foster In this programme, we explore six of Wigmore Hall is a no-smoking INTERVAL Organ venue. No recording or photographic Bach’s most fascinating works — some equipment may be taken into the Sarah Humphrys auditorium, nor used in any other part well known, others hardly known at of the Hall without the prior written Bach Recorder permission of the Hall Management. all. Each has its own story to tell, in Sinfonia to Cantata 169: Wigmore Hall is equipped with a Tuomo Suni ‘Loop’ to help hearing aid users receive illuminating Bach’s working processes Gott soll allein mein Herze haben clear sound without background Violin and revealing how he relentlessly noise. Patrons can use the facility by Bach switching their hearing aids over to ‘T’. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

“Early music is dead, long live early music!” The Holland Baroque ensemble and the Dutch early music revival Carine Hartman Student number: 6626726 MA Applied Musicology MA thesis Academic year 2018-2019 Utrecht University Supervisor: Dr. Ruxandra Marinescu Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my thesis supervisor, Dr. Ruxandra Marinescu. During the research process, she gave me helpful feedback and advice on my writings and I am grateful for her supervision. I also would like to thank Judith and Tineke Steenbrink from Holland Baroque for letting me interview them and answering further questions that I had considering this research. I also wish to thank Holland Baroque’s producer Clara van Meyel for contributing ideas to the research and giving me additional information on Holland Baroque. The organization of Holland Baroque in general has let me in on the ensemble’s ideas, vision and challenges and I am thankful for their open attitude towards me. I thank my friends for their interest in my research and their additional knowledge. Lastly, I thank my mother, father and sister and my boyfriend in particular for their motivational words and sympathy, which have helped me to complete this thesis. I hope you enjoy reading my thesis. 1 Table of contents ABSTRACT 3 INTRODUCTION 4 CHAPTER 1. THE HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE PRACTICE DEBATE 7 1.1 SCHOLARLY VIEWS ON HIP 7 1.1.1 “Getting it right” 9 1.1.2 The “literalistic performance” 11 1.1.3 Period instruments 12 1.2 THE DUTCH EARLY MUSIC MOVEMENT 14 1.3 A NEW GENERATION 15 CHAPTER 2. -

Bach and the Rationalist Philosophy of Wolff, Leibniz and Spinoza,” 60-71

Chapter 1 On the Musically Theological in Bach’s Cantatas From informal Internet discussion groups to specialized aca demic conferences and publications, an ongoing debate has raged on whether J. S. Bach ought to be considered a purely artistic or also a religious figure.^ A recently formed but now disbanded group of scholars, the Internationale Arbeitsgemeinschaft fiir theologische Bachforschung, made up mostly of German theologians, has made significant contributions toward understanding the religious con texts of Bach’s liturgical music.^ These writers have not entirely captured the attention or respect of the wider world of Bach 1. For the academic side, the most influential has been Friedrich Blume, “Umrisse eines neuen Bach-Bildes,” Musica 16 (1962): 169-176, translated as “Outlines of a New Picture of Bach,” Music and Letters 44 (1963): 214-227. The most impor tant responses include Alfred Durr, “Zum Wandel des Bach-Bildes: Zu Friedrich Blumes Mainzer Vortrag,” Musik und Kirche 32 (1962): 145-152; see also Friedrich Blume, “Antwort von Friedrich Blume,” Musik und Kirche 32 (1962): 153-156; Friedrich Smend, “Was bleibt? Zu Friedrich Blumes Bach-Bild,” DerKirchenmusiker 13 (1962): 178-188; and Gerhard Herz, “Toward a New Image of Bach,” Bach 1, no. 4 (1970): 9-27, and Bach 2, no. 1 (1971): 7-28 (reprinted in Essays on J. S. Bach [Ann Arbor: UMI Reseach Press, 1985], 149-184). 2. For a convenient list of the group’s main publications, see Daniel R. Melamed and Michael Marissen, An Introduction to Bach Studies (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 15. For a full bibliography to 1996, see Renate Steiger, ed., Theologische Bachforschung heute: Dokumentation und Bibliographie der Intemationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fiir theologische Bachforschung 1976-1996 (Glienicke and Berlin: Galda and Walch, 1998), 353-445. -

2017-2018 Season

2017– 2018 1 Welcome IT GIVES ME GREAT Passion. If you favour PLEASURE to introduce Bach’s John Passion, visit us such a stimulating in Perth where we will be programme of events for our reconstructing the full Good 2013–14 season. We will be Friday liturgy. appearing across Scotland and Europe to perform not Whilst we retain our focus just the familiar Dunedin on Bach and the eighteenth- favourites, but also a number century, we will also be of works that are new to our looking back into the repertoire. previous century exploring the heart-wrenching music We open with one of the best-loved of Italian composer, Claudio Monteverdi. choral works, Mozart’s Requiem, which To round off the season we perform for we will also be recording for Linn in the first time with the internationally- September. With a characteristically renowned countertenor Iestyn Davies fresh take on the classic, we will give you in Edinburgh and at the Wigmore Hall a chance to hear us perform it for the in London, in some sublime yet rarely first time in both Perth and Haddington, heard music by Johann Christoph Bach, the latter marking our return once again Johann Sebastian’s second cousin. This to the Lammermuir Festival. will also be the first of our Bach 300 project where during the course of 2014 After a quick visit to Brittany in the we will be tracking Bach’s work during Autumn to perform Bach’s John Passion 1714. Keep tuned for more details at the Lanvellec Festival, we return for throughout the season. -

Virtual BACH FESTIVAL OREGON BACH FESTIVAL 2021

LISTENING GUIDE June 25- July 11, 2021 OREGONVirtual BACH FESTIVAL OREGON BACH FESTIVAL 2021 Welcome to the 2021 Oregon Bach Festival In times of uncertainty, music is a constant in our lives. Music offers catharsis. It keeps us entertained, conjures memories, and expresses our deepest emotions.Music is everywhere. And during this divisive and tumultuous moment, we’re grateful that music is a powerful and relentless force that universally connects us. As we continue to fight a world-wide pandemic together, OBF invites you to join the global community of music lovers who will listen and watch the 2021 virtual Festival from the comfort and safety of their own spaces.All events are presented free and on-demand. A new concert is posted every day at noon and, unless otherwise noted, will remain available throughout the Festival. Whether you’re watching at home alone or you’re gathered with a socially distanced group of friends for a watch party, we hope you enjoy the 2021 slate of brilliant works. We’ll see you for a return to live music in 2022! June 25 Bach Listening Room with Matt Haimovitz June 25 Dunedin Consort: Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos 5 & 6 June 26 Paul Jacobs: Handel & Bach Recital June 27 To the Distant Beloved with Tyler Duncan June 28 Visions of the Future Part 1: Miguel Harth-Bedoya (48 hours only) June 29 Dunedin Consort: Lagrime Mie June 30 Visions of the Future Part 2: Eric Jacobsen (48 hours only) July 1 Emerson String Quartet July 2 Visions of the Future Part 3: Julian Wachner (48 hours only) July 3 Lara Downes presents -

A 16Th-Century Meeting of England & Spain

A 16th-Century Meeting of England & Spain Blue Heron with special guest Ensemble Plus Ultra Saturday, October 15, 2011 · 8 pm | First Church in Cambridge, Congregational Sunday, October 16, 2011 · 4 pm | St. Ignatius of Antioch Episcopal Church, New York City A 16th-Century Meeting of England & Spain Blue Heron with special guest Ensemble Plus Ultra Saturday, October 15, 2011 · 8 pm | First Church in Cambridge, Congregational Sunday, October 16, 2011 · 4 pm | St. Ignatius of Antioch Episcopal Church, New York City Program Blue Heron & Ensemble Plus Ultra John Browne (fl. c. 1500) O Maria salvatoris mater a 8 Blue Heron Richard Pygott (c. 1485–1549) Salve regina a 5 intermission Ensemble Plus Ultra Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548–1611) Ave Maria a 8 Ave regina caelorum a 8 Victoria Vidi speciosam a 6 Vadam et circuibo civitatem a 6 Nigra sum sed formosa a 6 Ensemble Plus Ultra & Blue Heron Victoria Laetatus sum a 12 Francisco Guerrero (1528–99) Duo seraphim a 12 Blue Heron treble Julia Steinbok Teresa Wakim Shari Wilson mean Jennifer Ashe Pamela Dellal Martin Near contratenor Owen McIntosh Jason McStoots tenor Michael Barrett Sumner Thompson bass Paul Guttry Ulysses Thomas Peter Walker Scott etcalfe,M director Ensemble Plus Ultra Amy Moore, soprano Katie Trethewey, soprano Clare Wilkinson, mezzo-soprano David Martin, alto William Balkwill, tenor Tom Phillips, tenor Simon Gallear, baritone Jimmy Holliday, bass Michael Noone, director Blue Heron · 45 Ash Street, Auburndale MA 02466 (617) 960-7956 · [email protected] · www.blueheronchoir.org Blue Heron Renaissance Choir, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt entity.