An Analysis of the Bhagyalakshmi Scheme in Karnataka Suggestions for Creating New Pathways to Empowerment of Girls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONGRATULATIONS New World Team

MARCH 2021 CONGRATULATIONS New World Team • A S ABILASH & NEETHU ABILASH, KODAKARA • BEGUM AZIZA & MOHAMMED IBRAHIM, HYDERABAD • A S BHAGYASHREE , DAVANGERE • BEGUM HASEENA & ABDUL SATTAR, SHIMOGA • A UMERA BANU , DODDABALLAPUR • BEHERA CHINMAY , CUTTACK • AASHIMA , HANSI • BELERI NAGAPPA & B S PRATIMADEVI, KOPPAL • ABASAHEB GARJE KANTILAL & ANITA KANTILAL GARJE, • BHAGAT JOLLY , AGRA AHMED NAGAR • BHANAP SAMPADA SUHAS , AURANGABAD • ABRAHAM BENNY , KANNUR • BHANGE ROHINI DNYANDEO & RAVINDRA BANDOPANT • AFZAAL AHMED KHAN ABU HURAIRAH , AURANGABAD BODAKHE, NEVASA • AGADI MUKTHUM SAB & BABIJAN MUKTHUMSAB • BHARATH KUMAR AKULA & A SWATHI, AGAGI, UTTARA KANNADA MAHABUBNAGAR • AGARWAL SHEETAL , SUNDERGARH • BHARGAVA UDBHAV , NEW DELHI • AGRAWAL SONIKA , JASHPUR • BHARGAVI R & R DINESHKUMAR, COIMBATORE • ALAPATI DIVYA , WEST GODAVARI • BHAVANA , KARNAL • ALI KASEM & NASIMA BEGUM, SONITPUR • BHAVSAR SIDDHI DHAVAL , AHMEDABAD • AMBIKA HD & HD NAGABHUSHANA, ANANTHAPUR • BINESH , NANMANDA • AMIL , MEERUT • BISWAS SHARMISTHA , BARDHAMAN • ANASUYAMMA & VENKATARAMAPPA, ANANTHAPUR • BOBBILI DHANPAL REDDY & BOBBILI SWETHA, • ANIRUDDHA B V , CHICKMAGALUR HYDERABAD • ANJALI , KARNAL • BODRAVARA MUNIRAJA & BASAMMA P, DAVANGERE • ANJUM SHABANA & SARWAR NISHAT, DHANBAD • BROJEN SINGH THONGAM & THONGAM SUNIBALA, • ANNAPOORANI V & A PARUMAL, COIMBATORE THOUBAL • ANWARHUSSAIN KAKHANDKI MOHAMMED KHALID , • BUNKAR MOHAN LAL , RAJSAMAND BAGALKOT • BURADE CHAYA RAVINDRA & RAVINDRA SURYAKANT • ARCHANA SHASHI & SATISH KUMAR, PATNA BURADE, SOLAPUR • ARI KISHORE KUMAR -

ISCCP – 2019 Scientific Program Day 1: Friday, 19Th April 2019

ISCCP – 2019 Scientific Program Day 1: Friday, 19th April 2019 WORKSHOPS 8.00 AM to 8.50 AM: Registration 8.50 AM to 9.00 AM: Welcome by Dr. Vijay Zutshi, Chair, Workshops Committee Hall 1: Coordinators: Dr. V. Priyanka and Dr. Phani Madhavi Workshop 1: Understanding Colposcopy & treatment for CIN: 9.00 AM to 5.00 PM Convener: Dr. Sweta Balani Co-Conveners: Dr. Mamta Dagar Session 1: 9.00 am to 10.00 am: Basics Chairpersons: Dr. D. Jyothi, Dr. B. Krishnamma, Dr. Devika Rathi, Dr. Usha Raina Time Topic Speaker 9.00 am to 9.15 am HPV infection and CIN Dr. Veena Acharya 9.15 am to 9.30 am Screen positive women, what next? Dr. Sweta Balani 9.30 am to 9.45 am Tissue basis of colposcopy Dr. Sumita Mehta 9.30 am to 9.45 am Interaction 10.00 am to 10.20 am Coffee Break Session 2: 10.20 am to 11.30 am: Colposcopic Diagnosis Chairpersons: Dr. Reddy Rani, Dr. Suresh Babu, Dr. Parimala John and Dr. Pratibha Singh 10.20 am to 10.35 am Equipment, instruments & maintenance Dr. Geethanjali Amin 10.35 am to 10.50 am Normal and abnormal colposcopy Dr. Meena Naik 10.50 am to 11.05 am Colposcopy in challenging situations Dr. Sakunthala Baliga 11.05 am to 11.20 am IFCPC nomenclature and scoring system Dr. Mamta Dagar 11.20 am to 11.30 am Interaction Session 3: 11.30 am to 1.00 pm: Treatment of CIN Chairpersons: Dr. R. Sasiprabha, Dr. Suneela Naidu, Dr. -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Professional-Address.Pdf

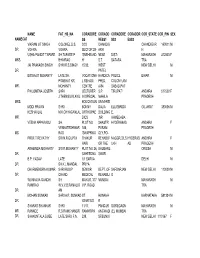

NAME FAT_HS_NA CORADDRE CORADD CORADDRE CORADDR COR_STATE COR_PIN SEX NAMECAT SS RESS1 SS2 ESS3 VIKRAM JIT SINGH COLONEL D.S. 3/33 CHANDIG CHANDIGAR 160011 M DR. VOHRA VOHRA SECTOR 28- ARH H USHA PANDIT TAPARE SH.TAPARE P 'SNEHBAND NEAR DIST- MAHARASH 412803 F MRS. BHIMRAO H' S.T. SATARA TRA JAI PRAKASH SINGH SHRI R.S.SINGH 15/32, WEST NEW DELHI M DR. PATEL BISWAJIT MOHANTY LATE SH. VOCATIONA HANDICA POLICE BIHAR M PRABHAT KR. L REHABI. PPED, COLONY,ANI MR. MOHANTY CENTRE A/84 SABAD,PAT PHILOMENA JOSEPH SHRI LECTURER S.P. TIRUPATI ANDHRA 517502 F J.THENGUVILAYIL IN SPECIAL MAHILA PRADESH MRS. EDUCATION UNIVERSI MODI PRAVIN SHRI BONNY DALIA ELLISBRIDG GUJARAT 380006 M KESHAVLAL M.K.CHHAGANLAL ORTHOPAE BUILDING E, MR. DICS ,NR AHMEDABA VEENA APPARASU SH. PLOT NO SHASTRI HYDERABAD ANDHRA F VENKATESHWAR 188, PURAM PRADESH MS. RAO 'SWAPRIKA' CLY,PO- PROF.T REVATHY SRI N.R.GUPTA THAKUR REHABI.F NAGGR,DILS HYDERAB ANDHRA F HARI OR THE UKH AD PRADESH ARABINDA MOHANTY SRI R.MOHANTY PLOT NO 24, BHUBANE ORISSA M DR. SAHEEDNA SWAR B.P. YADAV LATE 1/1 SARVA DELHI M DR. SH.K.L.MANDAL PRIYA DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHRI ROOP SENIOR DEPT. OF SAFDARJAN NEW DELHI 110029 M DR. CHAND MEDICAL REHABILI G WUNNAVA GANDHI SH MAYUR, 377 MUMBAI MAHARASH M RAMRAO W.V.V.B.RAMALIG V.P. ROAD TRA DR. AM MOHAN SUNKAD SHRI A.R. SUNKAD ST. HONAVA KARNATAKA 581334 M DR. IGNATIUS R SHARAS SHANKAR SHRI 11/17, PANDUR GOREGAON MAHARASH M MR. RANADE R.S.RAMCHANDR RAMKRIPA ANGWADI (E), MUMBAI TRA DR. -

Caprihans India Limited Kycdata List

Sr No of BANK MOBILE No FOLIONO NAME JOINTHOLDER1 JOINTHOLDER2 JOINTHOLDER3 ADDRESS1 ADDRESS2 ADDRESS3 ADDRESS4 CITY PINCODE Shares SIGNATURE PAN1 DETAILS NO EMAIL NOMINATION DIPTIKA SURESHCHANDRA RAGINI C/O SHIRISH I NEAR RAMJI 1 'D00824 BHATT SURESHCHANDRA TRIVEDI PANCH HATADIA MANDIR,BALASINOR 0 0 35 REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED CHHOTABHAI BIDI JETHABHAI PATEL MANUFACTURES,M.G.RO 2 'D01065 DAKSHA D.PATEL & CO. AD POST SAUGOR CITY 0 0 40 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED DEVIPRASAD DAHYABHAI BATUK DEVIPRASAD 1597 3 'D01137 SHUKLA SHUKLA SHRIRAMJINISHERI KHADIA AHMEDABAD 1 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED ANGODD MAPUSA 4 'E00112 EMIDIO DE SOUZA VINCENT D SOUZA MAPUSA CABIN BARDEZ GOA 0 0 70 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED 5 'R02772 RAMESH DEVIDAS POTDAR JAYSHREE RAMESH POTDAR GARDEN RAJA PETH AMRAVATI P O 0 0 50 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED SHASTRI GANESH BLOCK NO A‐ AMARKALAPATARU CO‐ NAGAR,DOMBIVALI 6 'A02130 ASHOK GANESH JOSHI VISHWANATH JOSHI 6/2ND FLOOR OP HSG SOCIETY WEST, 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED ARVINDBHAI CHIMANLAL NEAR MADHU PURA, 7 'A02201 PATEL DUDHILI NI DESH VALGE PARAMA UNJHA N.G. 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED ARVINDBHAI BHAILALBHAI A‐3 /104 ANMOL OPP NARANPURA NARANPURA 8 'A03187 PATEL TOWER TELEPHONE EXCHANGE SHANTINAGAR AHMEDABAD 0 0 140 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED MIG TENAMENT PREMLATA SURESHCHANDRA NO 8 GUJARAT GANDHINAGAR 9 'P01152 PATEL HSG BOARD SECT 27 GUJARAT 0 0 77 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED C/O M M SHAH, 10 'P01271 PIYUSHKUMAR SHAH MANUBHAI SHAH BLOCK NO 1, SEROGRAM SOCIETY, NIZAMPURA, BARODA 0 0 35 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED 169 THAPAR 11 'P02035 PREM NATH JAIN NAGAR MEERUT 0 0 50 REGISTERED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED REQUIRED 92/6 MITRA PARA DT. -

Tumkur Grain Merchants' Co-Op Bank Ltd., Administrative Office, Opp

Tumkur Grain Merchants' Co-op Bank Ltd., Administrative Office, Opp. Govt. Polytechnic, B H Road Tumkur DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED DEPOSITS BR. BR. AC. NO\CHQ Sl # CUST NAME\Details AC TYPE AMOUNT CODE NAME NO. 1 2 JCR SOWBHAGYA H S BANKERS CHQ 69164 14386.00 2 2 JCR SUSHEELA RAMESH BANKERS CHQ 70867 4000.00 3 2 JCR ASST DIRECTOR OF FACTORIES BANKERS CHQ 71182 160.00 4 2 JCR ASST DIRECTOR OF FACTORIES BANKERS CHQ 71183 640.00 5 2 JCR SUSHEELA RAMESH BANKERS CHQ 71274 2200.00 6 2 JCR MEHBOOB KHAN BANKERS CHQ 71391 1200.00 7 2 JCR H R BASAVARAJU BANKERS CHQ 71388 1000.00 8 2 JCR T C NATARAJ BANKERS CHQ 71392 700.00 9 2 JCR RAMESH T S BANKERS CHQ 71400 700.00 10 2 JCR T H HANUMANTHAPPA BANKERS CHQ 71396 490.00 11 2 JCR R T O BANKERS CHQ 71579 100.00 12 2 JCR COMMISSIONER CMC BANKERS CHQ 73201 50000.00 13 2 JCR SRINIVAS S R BANKERS CHQ 73442 10000.00 14 2 JCR ORIENTAL INSURANCE BANKERS CHQ 84044 209.00 15 2 JCR SREE PARSHWANATHA BANKERS CHQ 84236 805.00 16 2 JCR G H S CHITRASHEKAR & SONS CU 522 423.52 17 2 JCR RAMESH TRADERS T A CU 523 11.68 18 2 JCR APPAJAPPA & SONS CU 525 213.95 19 2 JCR RUDRAPPA G & CO CU 530 24.39 20 2 JCR T GUBANNA & SONS CO CU 595 102.44 21 2 JCR KRISHNA TRAN & HARDWARE MERCHANT CU 601 146.48 22 2 JCR ABDUL BASHEER & CO CU 621 269.08 23 2 JCR PRABHUDEV CARRIERS CU 639 337.15 24 2 JCR PRAVEEN TRADERS CU 656 129.25 25 2 JCR VENKATACHALA SETTY A M & SONS CU 690 182.42 26 2 JCR K G N TRADERS CU 674 129.96 27 2 JCR SREE SHANKAR AGENCIES CU 681 84.77 28 2 JCR SREE NANJUNDESHWARA OIL TRADERS CU 698 133.37 29 2 JCR SUDARSHAN ENTERPRISES CU 720 188.00 30 2 JCR T K R BRICK & TILE WORKS CU 730 100.15 31 2 JCR SREE GANGADHARA TRADERS CU 784 40.78 32 2 JCR PANKAJA ENTERPRISES CU 785 120.21 33 2 JCR RUDRAPPA G & SONS CU 319 129.54 34 2 JCR KAMADHENU FINANCIERS CU 320 240.15 35 2 JCR SRI BALAJI TRADING CO CU 330 80.42 DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED DEPOSITS BR. -

St.Thomas College, (Autonomous) Thrissur

St.Thomas College, (Autonomous) Thrissur UG ADMISSION 2021 PROVISIONAL ALLOTMENT RANK LIST 24/08/2021 BA English & History (Double Main) Aided GENERAL - (Confirmed List) Rank Application Number Student Name Index Mark 1 STC2021UG00636 GAYATHRI MANMOHAN 1660 2 STC2021UG07967 ALWINS K WILSON KOOTHUR WILSON 1660 3 STC2021UG07043 ANNA MEHRI 1651 4 STC2021UG07089 AVANI C S CHANDRIKA SADANANDAN 1650 5 STC2021UG01337 ANN AMBROSE MENACHERY 1641 6 STC2021UG05085 UNNIMAYA S NAIR UNNIMAYA SUDHAKARAN NAIR 1637 7 STC2021UG04908 ANSA ANTONY 1637 8 STC2021UG00899 ROSEMARY GEORGE 1637 9 STC2021UG07631 ALEENA SUNNY 1634 10 STC2021UG07582 VINAYAK S S SHALINI SREEJITH 1633 11 STC2021UG00441 DONA DAVIS 1633 12 STC2021UG09377 FATHIMA MASHAHIL UK UPPUKANDATHIL 1632 13 STC2021UG02442 THRISHA PRADEEP 1632 14 STC2021UG07676 SOURAV C B 1632 15 STC2021UG07616 AMAN REHMAN K P 1632 16 STC2021UG03287 ASWATHI T 1630 17 STC2021UG07079 AKHILA K KUNNATHUR 1630 18 STC2021UG08135 SREEKALA K J KAIPPULLY JAYAN 1629 19 STC2021UG05279 DISHNA A R AMMATT RAJAN 1628 20 STC2021UG09101 ANN MARY 1626 21 STC2021UG07163 AFLA KADER NP NALAKATH PILAKKATTIL 1625 22 STC2021UG00114 REVATHY O 1624 23 STC2021UG06787 NANDANA S JAYAN 1624 24 STC2021UG00659 BHAVITHA K S 1624 25 STC2021UG04126 FAIZA SAFEER 1623 26 STC2021UG00470 NIVEDITHA C.M CHALIPPATT MANOJ 1623 27 STC2021UG03918 ROSMARY BIJU 1623 28 STC2021UG02699 JENNA ANGEL JOSEPH 1622 29 STC2021UG04159 MINNU JOSEPH 1621 30 STC2021UG09637 KRISHNENDU S KUMAR 1621 GENERAL - (Waiting List) Rank Application Number Student Name Index Mark 1 STC2021UG01289 -

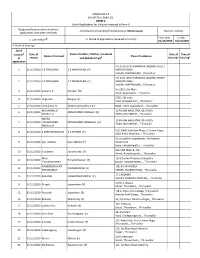

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Maduravoyal Revision identy applicaons have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Husband Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon NO 27/A, DEVI NARAYANA LAKSHMI STREET 1 01/12/2020 C E PRAKASAN C E NARAYANAN (F) MARUTHI RAM NAGAR, AYAPPAKKAM, , Thiruvallur NO 27/A, DEVI NARAYANA LAKSHMI STREET 2 01/12/2020 C E PRAKASAN C E NARAYANAN (F) MARUTHI RAM NAGAR, AYAPPAKKAM, , Thiruvallur No 2319, 5th Main 3 01/12/2020 Sumathi R Ramesh (H) Road, Ayapakkam, , Thiruvallur 2785, 5th main 4 01/12/2020 Jaiganesh Rangan (F) road, Ayyappakkam, , Thiruvallur 5 01/12/2020 Hemalatha D Dhatshinamoorthy K (H) 8640, TNHB, Ayapakkam, , Thiruvallur MOHAMMED 10 FA JAIN NAKSHTRA, 86 UNION 6 01/12/2020 MOHAMMED NORULLA (F) NASRULLA ROAD, NOLAMBUR, , Thiruvallur HAJIRA 10 FA JAIN NAKSHTRA, 86 UNION 7 01/12/2020 MOHAMMED MOHAMMED NASRULLA (H) ROAD, NOLAMBUR, , Thiruvallur NASRULLA C16, DABC Gokulam Phase 3, Sriram Nagar 8 01/12/2020 S SURIYAKRISHNAN K S SATHISH (F) Main Road, Nolambur, , Thiruvallur 42 sri Lakshmi apartments, 3rd Avenue 9 01/12/2020 sijo mathew biju mathew (F) millennium town, adayalampau, , Thiruvallur 312 VNR Milford, 7th 10 01/12/2020 Sundaram savarimuthu (F) Street, -

Annexure 1B 18416

Annexure 1 B List of taxpayers allotted to State having turnover of more than or equal to 1.5 Crore Sl.No Taxpayers Name GSTIN 1 BROTHERS OF ST.GABRIEL EDUCATION SOCIETY 36AAAAB0175C1ZE 2 BALAJI BEEDI PRODUCERS PRODUCTIVE INDUSTRIAL COOPERATIVE SOCIETY LIMITED 36AAAAB7475M1ZC 3 CENTRAL POWER RESEARCH INSTITUTE 36AAAAC0268P1ZK 4 CO OPERATIVE ELECTRIC SUPPLY SOCIETY LTD 36AAAAC0346G1Z8 5 CENTRE FOR MATERIALS FOR ELECTRONIC TECHNOLOGY 36AAAAC0801E1ZK 6 CYBER SPAZIO OWNERS WELFARE ASSOCIATION 36AAAAC5706G1Z2 7 DHANALAXMI DHANYA VITHANA RAITHU PARASPARA SAHAKARA PARIMITHA SANGHAM 36AAAAD2220N1ZZ 8 DSRB ASSOCIATES 36AAAAD7272Q1Z7 9 D S R EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY 36AAAAD7497D1ZN 10 DIRECTOR SAINIK WELFARE 36AAAAD9115E1Z2 11 GIRIJAN PRIMARY COOPE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED ADILABAD 36AAAAG4299E1ZO 12 GIRIJAN PRIMARY CO OP MARKETING SOCIETY LTD UTNOOR 36AAAAG4426D1Z5 13 GIRIJANA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE MARKETING SOCIETY LIMITED VENKATAPURAM 36AAAAG5461E1ZY 14 GANGA HITECH CITY 2 SOCIETY 36AAAAG6290R1Z2 15 GSK - VISHWA (JV) 36AAAAG8669E1ZI 16 HASSAN CO OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UNION LTD 36AAAAH0229B1ZF 17 HCC SEW MEIL JOINT VENTURE 36AAAAH3286Q1Z5 18 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED 36AAAAI0050M1ZW 19 INDU FORTUNE FIELDS GARDENIA APARTMENT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 36AAAAI4338L1ZJ 20 INDUR INTIDEEPAM MUTUAL AIDED CO-OP THRIFT/CREDIT SOC FEDERATION LIMITED 36AAAAI5080P1ZA 21 INSURANCE INFORMATION BUREAU OF INDIA 36AAAAI6771M1Z8 22 INSTITUTE OF DEFENCE SCIENTISTS AND TECHNOLOGISTS 36AAAAI7233A1Z6 23 KARNATAKA CO-OPERATIVE MILK PRODUCER\S FEDERATION -

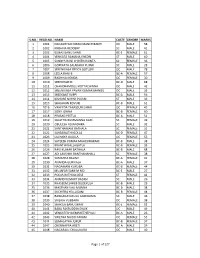

S.No. Regd.No. Name Caste Gender Marks 1 1001

S.NO. REGD.NO. NAME CASTE GENDER MARKS 1 1001 NAGASHYAM KIRAN MANCHIKANTI OC MALE 58 2 1002 KRISHNA REDDERY SC MALE 41 3 1003 ELMAS BANU SHAIK BC-E FEMALE 61 4 1004 VENKATA RAMANA KHEDRI ST MALE 60 5 1005 SANDYA RANI CHINTHAKUNTA SC FEMALE 36 6 1006 GOPINATH SALAKARU PUJARI SC MALE 28 7 1007 SREENIVASA REDDY GOTLURI OC MALE 78 8 1008 LEELA RANI B BC-A FEMALE 57 9 1009 RADHIKA KONDA OC FEMALE 30 10 1010 SREEDHAR M BC-D MALE 68 11 1011 CHANDRAMOULI KOTTACHINNA OC MALE 42 12 1012 SREENIVASA PAVAN KUMAR MANGU OC MALE 35 13 1013 SREEKANT SUPPI BC-A MALE 56 14 1014 KISHORE NAYAK PUJARI ST MALE 39 15 1015 SHAJAHAN KOVURI BC-B MALE 61 16 1016 VAHEEDA TABASSUM SHAIK OC FEMALE 45 17 1017 SONY JONNA BC-B FEMALE 60 18 1018 PRASAD PEETLA BC-A MALE 51 19 1019 SUJATHA BUMMANNA GARI SC FEMALE 49 20 1020 OBULESH ADIANDHRA SC MALE 32 21 1021 SANTHAMANI BATHALA SC FEMALE 31 22 1022 SARASWATHI GOLLA BC-D FEMALE 47 23 1023 LAVANYA GAJULA OC FEMALE 55 24 1024 SATEESH KUMAR MAHESWARAM BC-B MALE 38 25 1025 KRANTHI NALLAGATLA BC-B FEMALE 33 26 1026 RAVI KUMAR BATHALA BC-B MALE 68 27 1027 ADI LAKSHMI BANTHANAHALL SC FEMALE 38 28 1028 SAMATHA BALIMI BC-A FEMALE 41 29 1030 ANANDA GURIKALA BC-A MALE 37 30 1031 NAGAMANI KURUBA BC-B FEMALE 44 31 1032 MUJAFAR SAMI M MD BC-E MALE 27 32 1033 POOJA RATHOD DESE ST FEMALE 42 33 1034 ANAND KUMART BADIGI SC MALE 26 34 1035 KHASEEM SAHEB DUDEKULA BC-B MALE 29 35 1036 MASTHAN VALI MUNNA BC-B MALE 38 36 1037 SUCHITRA YELLUGANI BC-B FEMALE 44 37 1038 RANGANAYAKULU GUDIDAMA SC MALE 46 38 1039 SAILAJA VUBBARA OC FEMALE 38 39 1040 SHAKILA BANU SHAIK BC-E FEMALE 52 40 1041 BABA FAKRUDDIN SHAIK OC MALE 49 41 1042 VENKATESH DEMAKETHEPALLI BC-A MALE 26 42 1043 SWETHA NAIDU PAKAM OC FEMALE 55 43 1044 SUMALATHA JUKUR BC-B FEMALE 37 44 1047 CHENNAPPA ARETI BC-A MALE 29 45 1048 NAGARAJU CHALUKURU OC MALE 40 Page 1 of 127 S.NO. -

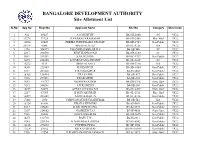

Finalprint 30X40

BANGALORE DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Site Allotment List Sl.NoApp No Regn No Applicant Name Site No Category Dimension 1932 89027 A S MURTHY B6-SH-5880 SC 9X12 211276 19325 G VENKATARAMAIAH B8-SG-2480 Phy. Hnd 9X12 311824 10820 PREMA INDUDHARA SWAMY B6-SD-1965 Gen Public 9X12 421678 6046 MANGALA H S B6-SL-5326 IIA 9X12 52136 304377 CHANDRASHEKAR R S B6-SB-540 SC 9X12 64237 298590 RENUKAPRASAD B4-SD-1680 SC 9X12 79041 254381 S MUKUNDA B4-SC-1313 Gen Public 9X12 86475 288280 G NARAYANA SWAMY B1-SL-2338 SC 9X12 914272 4115 DHAYALAN G B1-SH-1140 IIA 9X12 1014301 225585 RAJESH H R B9-SD-1464 Gen Public 9X12 11 8517 207850 Y R SHAHAPUR B2-SI-5868 Gen Public 9X12 1218368 138414 PRAVATHI B6-SB-437 Gen Public 9X12 137416 297471 PRAKASH R B1-SK-435 Gen Public 9X12 145659 414717 VISHWANATH H B6-SD-1546 State Govt 9X12 159212 344241 S R RAMESH B6-SB-504 Gen Public 9X12 1614219 52892 APPAJI GOWDA N R B6-SE-2497 State Govt 9X12 172217 17105 B SHIVAKUMAR B1-SL-2311 Phy. Hnd 9X12 1810499 203621 ANITHA RAJU S B1-SL-2316 Gen Public 9X12 1917402 1050 VISHWANATH B CHADICHAL B6-SB-543 IIA 9X12 2016924 81656 UDAYA KUMARI B6-SJ-4601 Gen Public 9X12 216912 235651 KARI GOWDA H S B7-SJ-5721 Gen Public 9X12 229207 324952 NASREEN TAJ B7-SI-4665 State Govt 9X12 235548 20686 SHIVALINGAIAH B4-SD-1695 Gen Public 9X12 2414471 132710 RAJU T N B2-SI-2811 Gen Public 9X12 258943 225934 K NAGARAJA ADIGA B7-SE-6542 Gen Public 9X12 2611126 275872 PUTTEGOWDA B8-SF-1961 Gen Public 9X12 2717574 69552 RITA GURURAJ B6-SG-5514/I Gen Public 9X12 289509 27554 D R SHIVANAND H LENGATI B7-SJ-5073 -

List-1 - Female Candidates of Southern Region Qualified Against State-Wise Vacancies

Staff Selection Commission (SR) Chennai CONSTABLE(GD) IN CAPFs, NIA & SSF AND RIFLEMAN(GD) IN ASSAM RIFLES EXAMINATION 2015 - Result for Female Candidates to be called for Medical Examination List-1 - Female Candidates of Southern Region qualified against State-wise vacancies Sl. No Roll Number Name of the Candidate Cat1 Cat2 Cat3 1 8002002425 TALAPALA NAGARANI 2 2 8002004019 PEDADA POLAMMA 6 3 8002004675 PODEM VAMSILATHA 2 4 8002005020 MOTANI KAMALA 1 5 8002007128 POLEBOINA SARITHA 2 6 8002008713 P DIVYA 2 7 8002010880 PAYAM SANDHYARANI 2 8 8002011643 TIRUPATAMMA AREPALLI 6 9 8002011868 KOPPALAKONDA SRUTHI 6 10 8002011938 K ANURADHA 6 11 8002011961 SHIVARATHRI KAVITHA 6 12 8002013830 PAMARTHI LAKSHMI TIRUPATHAMMA 2 13 8002016638 KUDUMULA MAHESWARI 6 14 8002017157 GUGULOTHU BHAVANI 2 15 8002017260 PUSHPALA CHANDRAKALA 16 8002017952 BHUKYA RAJAMANI 2 17 8002018540 GUNJI VENKATA RAMANA 6 18 8002019131 JARAGALA SWATHI 19 8002019226 GUGULOTH PRIYANKA 2 20 8002020230 MUTTARASI NEELAVATHI 6 21 8002020373 T RAMALAKSHMI 6 22 8002021058 DADEPOGU RENUKA 1 23 8002021702 GUGULOTHU VIJAYA 2 24 8002022407 MITAYIGIRI RAZIYABEE 6 25 8002022751 THOTA SUKANYA 6 26 8002023428 DHARAVATH SRILATHA 2 27 8002023775 BHUKYA SHIRISHA 2 28 8002023853 G ROJA 2 29 8002024999 ESLAWTH JAGADAMBA 2 30 8002025337 KHARAM PRIYANKA 2 31 8002025391 JETTY MOUNAVENI 6 32 8002026817 MUNJA SUMALATHA 6 33 8002027714 DANDUGULA JYOTHI 6 34 8002028763 SANGARABOINA SWAPNA 6 35 8002029213 ATNALA SHILPARANI 6 36 8002030026 KURUVA SUSEELA 6 37 8002030161 MUDAVATH RAJITHA 2 38 8002031021