Brook House Immigration Removal Centre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erss-Preferred-Suppliers

Preferred Suppliers for the Employment Related Support Services Framework : Lot 1: South East Organisations Contact Details A4e Ralelah Khokher Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0114 289 4729 Atos Origin Philip Chalmers Email: [email protected] Avanta Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0151 355 7854 BBWR Tony Byers Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0208 269 8700 Eaga Jenni Newberry Email: [email protected] Telephone 0191 245 8619 Exemplas Email: [email protected] G4S Pat Roach Email: [email protected], Telephone: 01909 513 413 JHP Group Steve O’Hare Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0247 630 8746 Maximus Email: [email protected] Newcastle College Group Raoul Robinson Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0114 289 8428 Sarina Russo Philip Dack Email: [email protected], Telephone: 02476 238 168 Seetec Rupert Melvin Email: [email protected], Telephone: 01702 201 070 Serco Shomsia Ali Email: [email protected], Telephone: 07738 894 287 Skills Training UK Graham Clarke Email: [email protected], Telephone: 020 8903 4713 Twin Training Jo Leaver Email: [email protected], Telephone: 020 8297 3269 Lot 2: South West Organisations Contact Details BBWR Tony Byers, Email: [email protected], Telephone: 020 8269 8700 BTCV Sue Pearson Email: [email protected], Telephone: 0114 290 1253 Campbell Page Email: [email protected] Groundwork Graham Duxbury Email: [email protected], -

Mutual Support Merchandise

www.mutual-support.org.uk March 2017 Views from Sunningdale Park Hotel—Booking form enclosed Multiple Sclerosis Society. Registered charity nos. 1139257/ SCO41990. Registered as a limited company in England and Wales no. 07451571 Mutual Support Patrons Dr Faraz Jeddi MBBS, MRCS(Ed), AFRCS(Ire), Pg Dip In RM Dr Anita Rose B.A. (hons), D.Clin Psy., AFBPsS, C. Psychol President Air Commodore Mike Barter CBE Honorary Life President Air Vice Marshal TB Sherrington CB OBE Vice President's Kim Bartlett Col Paul Cummings Air Commodore R Merry MB BS FRCP MRCPsych RCOG Honorary Members Christine Jones Roger Langdon MBE Lieutenant Colonel C S MacGregor KRH Stephanie Millward MBE Alastair Hignall CBE Newsletter Articles To Be Sent To: Liz & Neil Abrahams Newsletter Editor 10 Redriff Road Romford Essex RM7 8HD [email protected] Newsletter Deadline For : Sunday 26th March 2017 Cover Photo: Tripadvisor Sunningdale Park Hotel Chair’s Address I am delighted to announce The Soldiers Charity has once again shown its strong support of our work by giving us a grant of £8k towards general expenses in support of our Army members. Without funding like this we could not do what we do so our most sincere thanks go to everyone at the charity who made this happen for us – and in record time too! Everything crossed for a similar response from the other big donors this year. The audit I mentioned in the last couple of newsletters has finally been published and Simeon & I will now meet with The Society to discuss the next steps. -

Nigel Lawrence [email protected] DWP Central Freedom of Information Team Caxton House 6-12 Tothill Stre

DWP Central Freedom of Information Team Caxton House 6-12 Tothill Street London SW1H 9NA Nigel Lawrence freedom-of-information- [email protected] [email protected] DWP Website Our Ref: FOI2020/69472 7 December 2020 Dear Nigel Lawrence, Thank you for your Freedom of Information (FoI) request received on 12 November. You asked for: “Please provide a list of all private sector organisations to which DWP has awarded a contract to purchases services in connection with the provision of any interventions designed to help claimants to enter the labour market. My request includes, but is not limited to, employability courses and individual employment advice including tailored assistance with completing employment applications.” DWP Response I can confirm that the Department holds the information you are seeking for contracts awarded since 2009. Since 2009 DWP Employment Category has awarded contracts for interventions designed to help claimants enter the labour market to the following providers. 15billion 3SC A4e Ltd Aberdeen Foyer Access to Industry Acorn Training Advance Housing & Support Ltd ADVANCED PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT GROUP (UK) LIMITED Adviza Partnership Amacus Ltd Apex Scotland APM UK Ltd Atos IT Services UK Limited Autism Alliance UK Babington Business College Barnardo's 1 Best Practice Training & Development Ltd Burnley Telematics and Teleworking Limited Business Sense Associates C & K Careers Ltd Campbell Page Capital Engineering Group Holdings Capital Training Group Careers Development Group CDG-WISE Ability -

SFO V G4S Judgment

Case No: U20201392 IN THE CROWN COURT AT SOUTHWARK IN THE MATTER OF s.45 OF THE CRIME AND COURTS ACT 2013 Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 17/07/2020 Before : MR JUSTICE WILLIAM DAVIS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : SERIOUS FRAUD OFFICE Applicant - and - G4S CARE AND JUSTICE SERVICES (UK) Respondent LIMITED - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Crispin Aylett QC, Hannah Willcocks and Raoul Colvile (instructed by the SFO) for the Applicant Clare Montgomery QC and Katherine Hardcastle (instructed by Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP) for the Respondent Hearing dates: 10th and 17th July 2020 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment ............................. Mr Justice William Davis SFO v G4S C&J Approved Judgment Mr Justice William Davis: Introduction 1. G4S Care and Justice Services (UK) Limited (“G4S C&J”) is a private limited company registered in the United Kingdom. In 2018 the company reported net assets in excess of £85.5 million, revenue of over £341 million and profit of over £17.7 million. The principal activity of G4S C&J was described in the company’s 2018 annual report as “the provision of highly specialised services to central and local governments and government agencies and authorities including adult custody and rehabilitation, prisoner escorting and immigration services”. It is a wholly owned subsidiary of G4S plc, a public limited company incorporated in the United Kingdom. This parent company employs over 550,000 people worldwide. In 2019 its reported revenue was over £7.7 billion. In excess of £1.2 billion of that sum resulted from its operations in the United Kingdom. 2. Between 2005 and 2013 G4S C&J provided electronic monitoring services for the Ministry of Justice (“MoJ”). -

Securing Your World Our Purpose – Securing Your World

G4S plc Integrated Report and Accounts 2019 INTEGRATED REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019 Securing your world Our purpose – securing your world Who we are What we do Our Values G4S is the world’s leading global, integrated G4S plays a valuable and important role in security company. We offer a broad range society. As a major global employer we of security services delivered on a single, make a difference by helping people to live multi-service or integrated basis across six and work in safe and secure environments. continents. We have been investing in G4S takes a fully integrated approach to technology, software and systems. The its strategy and Corporate Social Group’s technology-related security Responsibility (CSR). See page 22 for revenues (see page 5) were over £3bn in more information on our CSR 2019 (2018: £2.8bn). approach and impact on society. Our values underpin everything we do and are brought to life by the behaviours and services provided by our 558,000 people each and every day. Highlights On 26 February 2020, G4S announced a significant milestone in the execution of its corporate strategy with an agreement to sell the majority of its conventional cash solutions businesses (the “Transaction”), greatly enhancing our strategic, commercial and operational focus. As at 28 April 2020, around 71% of the Transaction had completed. Statutory results1 Underlying results2 REVENUE OPERATING CASH FLOW REVENUE OPERATING CASH FLOW £7.8bn £504m £7.7bn £633m (2018: £7.5bn) (2018: £585m) (2018: £7.3bn) (2018: £582m) +3.4% -13.8% +4.7% +8.8% ADJUSTED PBITA3 PROFIT BEFORE TAX4 ADJUSTED PBITA3 EARNINGS £501m £27m £501m £263m (2018: £483m) (2018: £142m) (2018: £501m) (2018: £261m) +3.7% -81.0% +0.0% +0.8% Non-financial KPI EPS4 DIVIDEND PER SHARE5 EPS HEALTH AND SAFETY (5.9p) 3.59p 17.0p 67% (2018: 5.2p) (2018: 9.70p) (2018: 16.9p) REDUCTION IN ROAD TRAFFIC FATALITIES SINCE -213.5% +0.6% 2013 1. -

Adult Training Network

ADULT TRAINING NETWORK ATN REPORT FOR THE PERIOD AUGUST 2013 – JULY 2014 1 | P a g e Adult Training Network Annual Report 2013-2014 Contents Page Organisational Details 3 Mission Statement 3 Aims & Objectives 3 Company Structure 4 Training Centres 5 Business Plan & Aims and Objectives 6 - 7 Company Accounts 7 Staffing Establishment 7-8 Staff Development & Training 8 - 10 Partnership Agreements 10 Accreditation 11 Activities 2013 – 2014 11 -18 Richmond upon Thames College 10 – 14 Waltham Forest College 14 – 15 A4e - JCP Support Contract 16 A4e Professional and Executive and Graduate Programme 16 - 17 Ingeus Work Programme – Routeway Provider 17 Reed in Partnership – Work Programme Pilot 18 G4s – Community Work Placements (CWP) Programme 18 Reed – ESF Families Programme 19 Matrix Accreditation 19 External Verification & Inspection Reports 19-22 Extension Activities 22 -27 Good news stories & Case Studies 27-31 Future Developments & Priorities 31 Conclusion 32 2 | P a g e Adult Training Network Annual Report 2013-2014 ORGANISATIONAL DETAILS The Adult Training Network is a Registered Charity Number 1093609, established in July 1999, and a Company Limited by Guarantee number 42866151. The Head Office is at Unit 18, Arches Business Centre, Merrick Road, Southall, Middlesex, UB2 4AU. The Adult Training Network has a Board of Trustees and a Managing Director, who is the main contact person for the organisation. Further information on the Adult Training Network can be found on the organisation’s website at http://www.adult-training.org.uk. The Chair of the Board of Trustees is Mr Pinder Sagoo and the Managing Director is Mr Sarjeet Singh Gill. -

Work Programme Supply Chains

Work Programme Supply Chains The information contained in the table below reflects updates and changes to the Work Programme supply chains and is correct as at 30 September 2013. It is published in the interests of transparency. It is limited to those in supply chains delivering to prime providers as part of their tier 1 and 2 chains. Definitions of what these tiers incorporate vary from prime provider to prime provider. There are additional suppliers beyond these tiers who are largely to be called on to deliver one off, unique interventions in response to a particular participants needs and circumstances. The Department for Work and Pensions fully anticipate that supply chains will be dynamic, with scope to flex and evolve to reflect change within the labour market and participant needs. The Department intends to update this information at regular intervals (generally every 6 months) dependant on time and resources available. In addition to the Merlin standard, a robust process is in place for the Department to approve any supply chain changes and to ensure that the service on offer is not compromised or reduced. Comparison between the corrected March 2013 stock take and the September 2013 figures shows a net increase in the overall number of organisations in the supply chains across all sectors. The table below illustrates these changes Sector Number of organisations in the supply chain Private At 30 September 2013 - 367 compared to 351 at 31 March 2013 Public At 30 September 2013 - 128 compared to 124 at 30 March 2013 Voluntary or Community (VCS) At 30 September 2013 - 363 compared to 355 at 30 March 2013 Totals At 30 September 2013 - 858 organisations compared to 830 at March 2013. -

Document Title

Work Programme Contents At a Glance – Work Programme Introduction Change of circumstances Mandatory referrals Optional referrals / mandatory participation Voluntary referrals / voluntary participation Claimant working for 26 weeks or more and treated as an early completer Work Programme completers Light Touch regime At a Glance – Work Programme The Work Programme gives up to two years of extra support to claimants who need more help in finding and staying in work. The Work Programme provider decides how best to support claimants referred to them, through a ‘black box' approach. The last date for referrals to the Work Programme was 31st March 2017. All claimants referred on or before this date will remain on the Work Programme for up to 104 weeks even if they move into work, unless they complete the Work Programme early. Claimants were referred to the Work Programme at different points in their Universal Credit claim. A referral could either be mandatory or voluntary. Some voluntary referrals resulted in the claimant having to participate on a mandatory basis. A change in a claimant’s circumstances can result in changes to the nature of participation on the Work Programme and to their agreed commitments. Additional support is provided to claimants in the Intensive Work Search regime when they complete the Work Programme. Introduction The Work Programme provides up to two years of extra support to claimants who need more help in finding and staying in work. The Work Programme providers decide how best to support claimants referred to them, through a ‘black box' approach. The claimant’s Commitment provided the foundation for referral to the Work Programme and claimants were issued with a new Commitment as part of the referral process. -

DWP's Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health

DWP’s Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health Related Services (Release 5 October 2020) ERSA is pleased to be able to inform you of the organisations on Tier 1 and Tier 2 of the DWP Commercial Agreement for Employment and Health Related Services (CAEHRS). In total the DWP received submissions from 61 organisations with a total of 171 compliant submissions across the 7 regional lots. Overall, this has resulted in a total of 28 organisations being awarded a place on CAEHRS, 21 of which have multiple places and 7 have single awards. As set out during this competition the design of CAEHRS allows the department to offer further places they become available. The department does not currently have any plans to undertake further activity at this time but will formally notify the market as appropriate. Those that have been unsuccessful on this occasion are able to bid for future opportunities on CAEHRS. As communicated previously CAEHRS is already planned to be used for Scotland JETS delivery in Regional Lot 7 later this month and the Long-term unemployment programme that subject to further decisions will be outlined shortly. ERSA’s Chief Executive, Elizabeth Taylor said “This announcement is welcomed by the sector. ERSA is scheduling a series of events to provide more information about the successful organisations and the DWP’s plans, these events will keep the sector informed, build partnerships, and enable collaboration”. ERSA is running a series of Meet the Primes events, the first of which will be on Friday 23 October at 1pm. This will be followed by ERSA Member Forums based on the 7 CPA/ regional lot areas. -

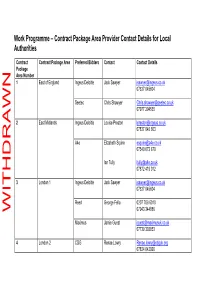

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities Contract Contract Package Area Preferred Bidders Contact Contact Details Package Area Number 1 East of England Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Seetec Chris Shawyer [email protected] 07977 294535 2 East Midlands Ingeus Deloitte Louise Preston [email protected] 07837 045 603 A4e Elizabeth Squire [email protected] 07540 673 670 Ian Tully [email protected] 07872 419 012 3 London 1 Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Reed George Fella 0207 708 6010 07943 344886 WITHDRAWN Maximus Jamie Guest [email protected] 07739 302853 4 London 2 CDG Renae Lowry [email protected] 07824 642926 Seetec Andrew Emerson [email protected] 07977 002278 A4e Jenny Smith [email protected] 07540 673678 Mark Roberts [email protected] 07545 423 778 5 North East Ingeus Deloitte Neil Johnson [email protected] 07557 281648 Avanta Kaye Rideout [email protected] (Regional Director) 07590 418294 6 North West 1 Ingeus Deloitte Barry Fletcher [email protected] 07800 624722 A4e Rhys Harris [email protected] 07872 424 457 Di Ainsworth [email protected] 07880 786707 7 North West 2 G4S George Selmer [email protected] 0161 618 1792 WITHDRAWN Avanta Marie Murray– [email protected] Henderson (Regional 07872 502912 Director) Amanda Stewart [email protected] (Regional Director) 07971 248945 Seetec Debra Fullerton [email protected] 0161 236 8964 8 -

UK Government Overview

Market Characteristics Government Key Characteristics Long Term Growth Drivers . Above group average margins . Focus on security . Significant G4S expertise - differentiation . Propensity to outsource . Consolidated markets . Opportunities for variation/extensions . Flexible cost base . Contracts for multiple Government agencies . Military security outsourcing . Care and justice outsourcing . Additional services/cross selling . Double digit market growth Market Participants Defensive Qualities . Serco . CRG . Long term contracts . Capita . XE . Price and cost indexation . VT/Babcock . Triple Canopy . Kalyx . Dyncorp . GEO . Olive . Reliance . Aegis . AKAL . IAP Worldwide Services 1 Government David Taylor -Smith, MBE Regional President and CEO G4S Secure Solutions UK and Ireland Contents . G4S UK Government overview . UK Government market dynamics . G4S UK Government strategy . G4S Global Government strategy . Wins, extensions and pipeline . Conclusions 3 G4S UK Government overview 2009 Revenue £m . Leading supplier of secure Police, 40 Education, 7 Foreign Office , 45 solutions to UK Government . Market leaders in justice, police and immigration Defence , 58 . £670m revenues in 2009 . Margins above group average Immigration , 81 Justice , 247 Health, 87 Welfare, 106 4 G4S UK Government overview Profile Justice Immigration Police Welfare 4 Prisons Electronic Monitoring 4 IRCs 30 Custody suites Prisoner Escorts Escorting 675 police/court cells 3 Secure Training Centres Repatriation Interim Staff Security services Technology Security Forensic medical Technology Security Technology Technology Manchester Courts PFI #1 - 70% Share Training overseas # 1 - 45% Share #1 Foreign Office Defence Health Other Met Office PPP 6 major hospitals GCHQ PFI Cabinet Office Pre-deployment & 175+ health centres FCO UK security HMRC SF training Patient transport Embassy Olympic Build Site Technology Technology protection in Temp security staff 24 countries ELCAS SOCA / DFID in Afghanistan 5 G4S UK Government Overview Ireland, N. -

National Audit Office Report (HC 832 2012-2013): a Commentary for the Committee of Public Accounts on the Work Programme Outcome

REPORT BY THE COMPTROLLER AND AUDITOR GENERAL HC 832 SESSION 2012-13 13 DECEMBER 2012 A commentary for the Committee of Public Accounts on the Work Programme outcome statistics Our vision is to help the nation spend wisely. We apply the unique perspective of public audit to help Parliament and government drive lasting improvement in public services. The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending for Parliament and is independent of government. The Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG), Amyas Morse, is an Officer of the House of Commons and leads the NAO, which employs some 860 staff. The C&AG certifies the accounts of all government departments and many other public sector bodies. He has statutory authority to examine and report to Parliament on whether departments and the bodies they fund have used their resources efficiently, effectively, and with economy. Our studies evaluate the value for money of public spending, nationally and locally. Our recommendations and reports on good practice help government improve public services, and our work led to audited savings of more than £1 billion in 2011. A commentary for the Committee of Public Accounts on the Work Programme outcome statistics Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 13 December 2012 This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the National Audit Act 1983 for presentation to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act Amyas Morse Comptroller and Auditor General National Audit Office 12 December 2012 HC 832 London: The Stationery Office £8.75 This note provides the Committee with a commentary on the Department’s statistics for Work Programme outcomes and makes reference where appropriate to other published material.