The Science and Sociology of Hunting: Shifting Practices and Perceptions in the United States and Great Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amending the Hunting Act 2004

BRIEFING PAPER Number 6853, 13 July 2015 Amending the Hunting By Elena Ares Act 2004 Inside: 1. The Hunting Act 2. Proposals to amend the Act 3. Reactions to the proposals www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 6853, 13 July 2015 2 Contents Summary 3 1. The Hunting Act 4 1.1 The legislation in practice 4 England and Wales 4 Scotland 6 1.2 Public opinion on fox hunting 7 2. Proposals to amend the Act 7 2.1 Procedure to amend the Act 8 2.2 July 2015 announcement 8 2.3 Proposed amendments to Schedule 1 9 Passage through Parliament 9 3. Reactions to the proposals 11 Contributing Authors: Author, Subject, Section of document Cover page image copyright: Chamber-051 by UK Parliament image. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped. 3 Amending the Hunting Act 2004 Summary Hunting with dogs was banned in England in 2004 under The Hunting Act. The legislation includes several exemptions which allow the use of a maximum of two dogs for certain hunting activities, including stalking and flushing. The exemptions under the Act can be amended using a statutory instrument with the approval of both Houses. The Conservative Government included a manifesto commitment to repeal the Hunting Act. However, in July 2015 the Government announced that it intended to amend the legislation to remove the limit on the number of dogs, and instead replace it with a requirement that the number of dogs used is appropriate to the terrain and any other relevant circumstance. -

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015 I. Introduction The Board of Directors (“Board”) has requested information relating to facility operations at the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range (“Chabot Gun Range” or “gun range”), including estimated capital and operation and maintenance costs required for continued operation of the gun range. As discussed below, District staff has gathered information regarding environmental compliance, facility conditions and deferred maintenance, sound impacts and mitigation options, and information related to use, revenue, and operational costs of the gun range. II. CEQA Compliance No action by the Board is being requested at this time, and therefore no action is necessary to comply with CEQA for purposes of this Board item. However, a decision by the Board to consider entry into a long term extension of the Chabot Gun Club’s lease would first require environmental review under CEQA, most likely the preparation of an environmental impact report (EIR). III. History of the Chabot Gun Range In 1963, the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range was developed in cooperation with the Oakland Pistol Club, which had previously leased a site in Knowland Park, Oakland, California. The original 1962 lease was a partnership between the District and the Oakland Pistol Club to construct, develop, operate and maintain a marksmanship range in Anthony Chabot Regional Park. In 1964, the original lease was amended to finalize the schedule and define the cost-share for construction of the Chabot Gun Range. In 1967, the District entered into a new long-term lease with Chabot Gun Club, Inc. -

American Water Spaniel

V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 1 American Water Spaniel Breed: American Water Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: United States First recognized by the AKC: 1940 Purpose:This spaniel was an all-around hunting dog, bred to retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground with relative ease. Parent club website: www.americanwaterspanielclub.org Nutritional recommendations: A true Medium-sized hunter and companion, so attention to healthy skin and heart are important. Visit www.royalcanin.us for recommendations for healthy American Water Spaniels. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 2 Brittany Breed: Brittany Group: Sporting Origin: France (Brittany province) First recognized by the AKC: 1934 Purpose:This spaniel was bred to assist hunters by point- ing and retrieving. He also makes a fine companion. Parent club website: www.clubs.akc.org/brit Nutritional recommendations: Visit www.royalcanin.us for innovative recommendations for your Medium- sized Brittany. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 4 Chesapeake Bay Retriever Breed: Chesapeake Bay Retriever Group: Sporting Origin: Mid-Atlantic United States First recognized by the AKC: 1886 Purpose:This American breed was designed to retrieve waterfowl in adverse weather and rough water. Parent club website: www.amchessieclub.org Nutritional recommendation: Keeping a lean body condition, strong bones and joints, and a keen eye are important nutritional factors for this avid retriever. Visit www.royalcanin.us for the most innovative nutritional recommendations for the different life stages of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 5 Clumber Spaniel Breed: Clumber Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: France First recognized by the AKC: 1878 Purpose:This spaniel was bred for hunting quietly in rough and adverse weather. -

Invitation for the European Lure Coursing Championship 2016

Invitation for the European Lure Coursing Championship 2016 Organization: FCI – Fédération Cynologique Internationale Execution: Slovenský klub chovateľov chrtov - Slovak Sighthound Club. Regulations: FCI Regulations for International Sighthound Races and Lure Coursing Events Information: www.coursing2016.eu Location: Penzión Sedlo, 966 74 Veľké Pole, Slovakia GPS coordinates: N 48.53995 – E 18.53401 Coursing director: Mr. Vlastislav Vojtek, Slovakia FCI delegates: Mrs. Veronika Kučerová Chrpová, Czech Republic Mrs. Agata Juszczyk, Poland Judges: The national organizations are invited to send a list of available judges together with entry form. Schedule: Friday 17th June 2016 starting at 8:00 o´clock: Galgo Espanol, Magyar Agar, Cirneco Dell´Etna, Podenco Ibicenco, Pharao Hound, Podenco Canario, Italian Greyhound, Italian Greyhound Sprinter, Whippet Sprinter Saturday 18th June 2016 starting at 8:00 o´clock: Barzoi, Deerhound, Irish Wolfhound, Saluki, Sloughi Sunday 19th June 2016 starting at 8:00 o´clock: Afghan Hound, Azawakh, Greyhound, Chart Polski, Whippet Depending on the number of dogs entered for the competition, breeds can be moved to another day. The definite breed schedules (reparation) will be published and communicated with the national organizations not later than 20th May 2016. Veterinary control: The veterinary control will be done at 15:00 – 18:00 hrs. only the day prior to the starting day. Valid vaccination passport, rabies vaccination according to regulations is mandatory, at least 21 days; vaccination passport has to be presented. Control measurement: According to the decision of the CdL Commission all Whippets and Italian Greyhounds which are not registered in the database will be remeasured in height upon registration at the veterinary inspection. -

2021 Camp Keowa Master Programming Schedule

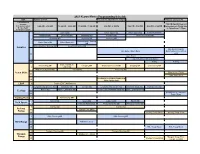

2021 Keowa Master Programming Schedule KEY Update: 2/17/21 ←Lunch 12:15pm/Siesta 1:00pm ←Dinner Lineup 5:45 I = instructional program 7:00 PM (Spirit Program) O = open program 9:00 AM - 9:50 AM 10:00 AM - 10:50 AM 11:00 AM - 11:50 AM 2:00 PM - 2:50 PM 3:00 PM - 3:50 PM 4:00 PM - 4:50 PM No program on Friday due B = bookable to Campfire at 7:30pm A = Adult Program BSA Guard Water Sports MB Water Sports MB Instructional Swim Swimming MB Swimming MB Swimming MB Kayaking MB Small Boat Sailing MB Lifesaving MB Kayaking MB Canoeing MB I Motor Boating / Rowing Water Sports MB Water Sports MB MB Aquatics Motor Boating / Rowing MB Small Boat Sailing MB Mile Swim/ Rowing Mile Swim (Thurs Only) Qualifications (Tues/Wed O only) Open Swim Open Boating (ends at 4:30pm) B Tubing Tubing Signs, Signals, & Geocaching MB Camping MB Wilderness Survival MB Camping MB Orienteering MB I Codes MB Wilderness Survival MB First Aid MB Pioneering MB Scout Skills Firem'n Chit (Thurs) O Totin' Chip (Tues) Introduction to Outdoor Leadership A Skills (Adults Only) LEAF I Project LEAF (AM Session) Envionmental Science MB Astronomy MB Forestry MB Environmental Science MB Mammal Study MB Plant Science MB I Ecology Nature MB Space Exploration MB Reptile and Amphibian Study MB Space Exploration MB Introduction to Leave No O Trace (Tues) Trading Post I Salemanship MB Fishing MB Sports MB Athletics MB Sports MB Field Sports I Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB I Archery MB Archery MB Archery O Archery Free Shoot Range B Archery Troop Shoot Archery -

'An Incredibly Vile Sport': Campaigns Against Otter Hunting in Britain

Rural History (2016) 27, 1, 000-000. © Cambridge University Press 2016 ‘An incredibly vile sport’: Campaigns against Otter Hunting in Britain, 1900-39 DANIEL ALLEN, CHARLES WATKINS AND DAVID MATLESS School of Physical and Geographical Sciences, University of Keele, ST5 5BG, UK [email protected] School of Geography, University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Otter hunting was a minor field sport in Britain but in the early years of the twentieth century a lively campaign to ban it was orchestrated by several individuals and anti-hunting societies. The sport became increasingly popular in the late nineteenth century and the Edwardian period. This paper examines the arguments and methods used in different anti-otter hunting campaigns 1900-1939 by organisations such as the Humanitarian League, the League for the Prohibition of Cruel Sports and the National Association for the Abolition of Cruel Sports. Introduction In 2010 a painting ‘normally considered too upsetting for modern tastes’ which ‘while impressive’ was also ‘undeniably "gruesome"’ was displayed at an exhibition of British sporting art at the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle. The Guardian reported that the grisly content of the painting was ‘the reason why it was taken off permanent display by its owners’ the Laing Gallery in Newcastle.1 The painting, Sir Edwin Landseer’s The Otter Speared, Portrait of the Earl of Aberdeen's Otterhounds, or the Otter Hunt had been associated with controversy since it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1844 Daniel Allen, Charles Watkins and David Matless 2 (Figure 1). -

HS NEWS Volume 22, Issue 01

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository Spring 1977 HS NEWS Volume 22, Issue 01 Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/v22_news Recommended Citation "HS NEWS Volume 22, Issue 01" (1977). HSUS News 1977. 4. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/v22_news/4 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASTERFILE COPY HutnaneThe Do Not Remove SPRING 1977 Vol. 22 No.1 soc•e"'. OF THE UNITED STAT:~ Let's Put Greyhound Racing Out of the Running! Let's Put Greyhound Racing The popularity of greyhound racing is increasing. According to a prevent it from becoming legal in other states. is that it is necessary for their dogs to be trained recent HSUS survey of the 50 state attorneys general, greyhound racing Recently, The HSUS and others did just that in in that way in order to be competitive with dogs has been legalized in 72% of the states which had it proposed in their the state of California where the voters were trained in other states where use of live rabbits legislatures during the past two years. Likewise, pari-mutuel or other asked to permit wagering at dog tracks. The is not illegal. The trainers suggest they would be wagering has been allowed at the dog tracks in each state adopting HSUS immediately issued and circulated a cheating the betting public if they didn't train greyhound racing. -

Our Action Plan for Animal Welfare Contents

Our Action Plan for Animal Welfare Contents Foreword by the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 3 Executive summary 5 Devolution and engagement 7 Sentience and enforcement 8 International trade and advocacy 9 Farm animals 12 Pets and sporting animals 14 Wild animals 17 Next steps 19 2 Our Action Plan for Animal Welfare Foreword by the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs We are a nation of animal lovers. The UK was the first country in the world to pass legislation to protect animals in 1822 with the Cruel Treatment of Cattle Act. We built on this to improve conditions related to slaughterhouses in 1875, and then passed the landmark Protection of Animals Act in 1911. The Animal Welfare Act 2006 introduced a robust framework and powers for protecting all kept animals in England and Wales. Since 2010 we have achieved remarkable things in animal welfare. On farms we introduced new regulations for minimum standards for meat chickens, banned the use of conventional battery cages for laying hens and made CCTV mandatory in slaughterhouses in England. For pets, microchipping became mandatory for dogs in 2015, we modernised our licensing system for a range of activities such as dog breeding and pet sales, have protected service animals via ‘Finn’s Law’ and banned the commercial third-party sales of puppies and kittens (‘Lucy’s Law’). In 2019 our Wild Animals in Circuses Act became law, and we have led work to implement humane trapping standards. But we are going to go further. Our manifesto was clear that high standards of animal welfare are one of the hallmarks of a civilised society. -

1-FWG-Presentation

Forensics Working Group FWG Terms of Reference • Published on Defra PAW website • Objective: to assist in combating wildlife crime through the promotion, development and measured review of DNA and forensic techniques • FWG supports the whole of PAW UK, providing tools to assist enforcers FWG Composition • Representatives of UK government departments, police, UK Border Agency, government endorsed forensic laboratories and secure NGOs • 2-3 meetings a year, informs and informed by PAW Steering Group Improved Information available • Collated cases that have used forensics • Awareness of tests available • Legal Eagle articles • Forensic Wildlife Crime Handbook (Oct 2012) • PAW / NWCU / TRACE websites Sampling Kits • Practical kit for use in the field • Maximising evidential opportunities • Easy -to -use • Consumable replacements • Advice and guidance, contacts Forensic Analysis Fund • Match-funding for wildlife forensic analysis • Information provided by investigator, assessed by FAF panel • Conditions of funding (media / costs) • New improved form (2012) • Communication and awareness • Monitoring of effectiveness FAF - Selected case studies 1. Illegal trade in ivory 2. Rhino horn smuggling 3. Hare coursing 1. Illegal ivory trade • Trade in ivory is only legal if it is from an elephant that died before 1947 and it is worked • Online trade opened a new opportunity for potential illegal trade in ivory • Age of ivory from appearance can be faked 1. Illegal ivory trade • NWCU had intelligence relating to potential illegal ivory sales on eBay • Alerted Hampshire Police who carried out a search on the premises • 33 items of ivory seized • Accused claimed they were pre 1947 • FWG suggested carbon dating 1. Illegal ivory trade • Radio-carbon dating – new forensic tool to date ivory • Nuclear bomb testing enrichment of C 14 since 1950s • Can identify ivory that is from elephants alive after the ban in trade (1947) 1. -

Technical Review 12-04 December 2012

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation Technical Review 12-04 December 2012 1 The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation The Wildlife Society and The Boone and Crockett Club Technical Review 12-04 - December 2012 Citation Organ, J.F., V. Geist, S.P. Mahoney, S. Williams, P.R. Krausman, G.R. Batcheller, T.A. Decker, R. Carmichael, P. Nanjappa, R. Regan, R.A. Medellin, R. Cantu, R.E. McCabe, S. Craven, G.M. Vecellio, and D.J. Decker. 2012. The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The Wildlife Society Technical Review 12-04. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Series Edited by Theodore A. Bookhout Copy Edit and Design Terra Rentz (AWB®), Managing Editor, The Wildlife Society Lisa Moore, Associate Editor, The Wildlife Society Maja Smith, Graphic Designer, MajaDesign, Inc. Cover Images Front cover, clockwise from upper left: 1) Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) kittens removed from den for marking and data collection as part of a long-term research study. Credit: John F. Organ; 2) A mixed flock of ducks and geese fly from a wetland area. Credit: Steve Hillebrand/USFWS; 3) A researcher attaches a radio transmitter to a short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma hernandesi) in Colorado’s Pawnee National Grassland. Credit: Laura Martin; 4) Rifle hunter Ron Jolly admires a mature white-tailed buck harvested by his wife on the family’s farm in Alabama. Credit: Tes Randle Jolly; 5) Caribou running along a northern peninsula of Newfoundland are part of a herd compositional survey. Credit: John F. Organ; 6) Wildlife veterinarian Lisa Wolfe assesses a captive mule deer during studies of density dependence in Colorado. -

HISTORICAL SKETCH of RURAL FIELD SPORTS in LANCASTER COUNTY by Herbert H

I. HISTORICAL SKETCH OF RURAL FIELD SPORTS IN LANCASTER COUNTY By Herbert H. Beck A consideration of the purposes and value of history requires that the historian be properly qualified as a witness before the bar of posterity. In cases such as the one at hand this qualification should reach the point of showing not only that the writer be in close and accurate touch with the past but that he have a technical knowledge of his subject. Before such examination the writer modestly presumes to eligibility. He believes that while this sketch might have been written by men whose memories reach farther back than his own by thirty of forty years, it could have been done by none of this generation perhaps whose interest in the field sports of Lancaster County has been keener nor whose experience has been more widely ranged than his over the various phases of the subject. From a boyhood in which the writings of Frank Forrester had their quick appeal and the sportsmen of his village took on a heroism he has found his keenest recreation afield. Following an ancient instinct which, though it may have softened, has not turned with years he has entered enthusias- tically at one time or another into all of the sportsmanly kinds of local hunting. He has splashed through the tussock swamps of many townships hunting snipe on the spring migration; he has been in parties of woodcock shooters in the days prior to 1904 when July cock-shooting was the accepted mid-summer sport; he has spent scores of August afternoons in the up- country farmlands in pursuit of -

Private Assistance in Outdoor Recreation. a Directory of Organizations Providing Aid to Individuals and Public Groups

DOCUMRNT IIRSUMIR ED 032 146' RC 002 882 Private Assistance in Outdoor Recreation. A Directory of Organizations Providing Aid to Individuals and Public Croups. Department of the Interior. Washington. D.C. Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. Pub Date 68 Note -38p. Available from-Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Covernment Printing Office. Washington. D. C. 20402 (0-285-370, $0.30). EDRS Price MF -$025 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors-AthleticActivities,*Directories,Hobbies.NationalOrganizations.Outdoor Education. *Publications, *Recreation. *Recreational Activities. Recreational Facilities, Resource Materials. *Technical Assistance . In an effort to aid private recreation area developers and operators. and other individuals interested in outdoor recreation, this Bureau of Outdoor Recreation publication lists a number of professional societies and national organizations providing low-cost publications and other aids to planning. development, and operation of outdoor recreation areas. Publications and type of assistance available are listed for the following recreational activities: archery. bicycling. boating and canoeing. camping. driving and sightseeing. fishing. hiking and walking for pleasure. horseback riding, hunting, nature study. outdoor games and sports. picnicking. skating. shooting preserves and ranges. skiing, and swimming. Related subjects of park management. public relations. and community action are also included. (SW) I t (.1 reNPrivate Assistance CDPOutdoor Recreation LLJ A DIRECTORY of ORGANIZATIONS PROVIDING AID to INDIVIDUALS and PUBLIC. GROUPS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION E WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. This is not a complete listing of organizations or publications.