Bertagna J Ed the Hockey Coaching Bible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008-09 Notre Dame Hockey Notes

lllllddddd Sports Information Office University of Notre Dame 112 Joyce Center 2008-09 NOTRE DAME Notre Dame, IN 46556 www.und.com 574-631-7516 574-631-7941 FAX HOCKEY NOTES 2008-09 NOTRE DAME Irish Open Home Schedule With Weekend Series Versus Sacred Heart HOCKEY (0-1-0/0-0-0-0) • Notre Dame looks for first win of the season after falling to Denver, 5-2, in the Hall of OCTOBER 11 $ at Hall of Fame Game Fame Game on Oct. 11. at #6/#6 Denver L, 2-5 17 Sacred Heart (und.com) 7:35 p.m. • Irish and Sacred Heart Pioneers meet for first time in program’s history. 18 Sacred Heart (und.com) 7:05 p.m. • Notre Dame begins four-game homestand that includes visits from Sacred Heart and 24 * Miami (und.com) 7:35 p.m. 25 * Miami (und.com) 7:05 p.m. CCHA foe Miami (Oct. 24-25). 31 * at Northern Michigan 7:35 p.m. • The Series: #8/#8 Notre Dame (0-1-0) vs. Sacred Heart University (0-2-0) NOVEMBER • Date/Site/Time: Fri.-Sat., October 17-18, 2008 • Joyce Center (2,713) • 7:35 p.m./7:05 p.m. 1 * at Northern Michigan 7:35 p.m. 7 at Boston College (ESPN Classic) 7:00 p.m. • Broadcast Information: Radio: Notre Dame hockey can be heard live on Cat Country 99.9 8 at Providence College 7:00 p.m. FM in South Bend. Mike Lockert, now in his seventh season will call all the action for the 14 * Lake Superior State (und.com) 7:35 p.m. -

CCHA Shootout Announcement Release

CENTRAL COLLEGIATE HOCKEY ASSOCIATION 23995 Freeway Park Drive, Suite 101 Farmington Hills, MI 48335 Phone: (248) 888-0600 • Fax: (248) 888-0664 [email protected] • www.ccha.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Fred Pletsch August 14, 2008 (248) 888-0600 CCHA TO UNVEIL SHOOTOUT IN 2008-09 CAMPAIGN Bonus Point Awarded to Tiebreaker Winner FARMINGTON HILLS, Mich. – The Central Collegiate Hockey Association announced today that an NHL style three-player shootout will be used in the 2008-09 season to determine a winner for all of the 168 regular-season conference games that are tied after 60 minutes of regulation play and fi ve minutes of overtime. “The shootout has proved to be an exciting addition to hockey at a variety of levels and we are anxious to bring it into college hockey. The drama it creates is very popular with fans, and importantly, today’s players love it,” stated CCHA Commissioner Tom Anastos, whose conference becomes the fi rst of college hockey’s six Division I men’s leagues to adopt the shootout. “At the same time, the NCAA rules and ice hockey committees have allowed us to implement this tie-breaker protocol so that every regular-season league game will have a winner while preserving the integrity of the national rankings because CCHA games decided by a shootout will still be considered ties for NCAA purposes. Bonus points awarded will impact the conference standings only.” The shootout concept has been enthusiastically endorsed by Greg Hammaren, the Vice President and General Manager of FSN Detroit, which will televise 17 CCHA regular-season and playoff games in 2008-09. -

Coaching Records

COACHING RECORDS Coaching Facts 61 Team-By-Team Won-Lost-Tied Records 63 All-Time Coaches 69 COACHING FACTS *Does not include vacated years.The 2020 tournament was not held due to .800—Vic Heyliger, Michigan, 1948-57 (16-4) the COVD-19 pandemic. .789—Gino Gasparini, North Dakota, 1979-90 (15-4) TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES .778—Scott Sandelin, Minn. Duluth, 2004-19 (21-6) 24—Jack Parker, Boston U., 1974-2012 .700—Rick Bennett, Union (NY), 2012-17 (7-3) 23—Red Berenson, Michigan, 1991-2016 .700—*Murray Armstrong, Denver, 1958-72 (14-6) 23—Jerry York, Bowling Green and Boston College, 1982-2016 .694—Bob Johnson, Wisconsin, 1970-82 (12-5-1) 22—Ron Mason, Bowling Green and Michigan St., 1977-2002 .667—Jim Montgomery, Denver, 2014-18 (8-4) 18—Richard Umile, New Hampshire, 1992-2013 .643—Ned Harkness, Rensselaer and Cornell, 1953-70 (9-5) 18—Don Lucia, Colorado Col. and Minnesota, 1995-2017 .638—Jerry York, Bowling Green and Boston College, 1982-2016 (41-23-1) 16—Jeff Jackson, Lake Superior St. and Notre Dame, 1991-2019 .625—Jeff Jackson, Lake Superior St. and Notre Dame, 1991-2019 (25-15) 13—Len Ceglarski, Clarkson and Boston College, 1962-91 .625—Jack Kelley, Boston U., 1966-72 (5-3) 13—George Gwozdecky, Miami (OH) and Denver, 1993-2013 .625—Tim Whitehead, Maine, 2002-07 (10-6) 12—Doug Woog, Minnesota, 1986-97 .607—Dave Hakstol, North Dakota, 2005-15 (17-11) 12—*Jeff Sauer, Colorado Col. and Wisconsin, 1978-2001 .606—Shawn Walsh, Maine, 1987-2001 (20-13) 12—Mike Shafer, Cornell, 1996-2019 OACHED WO IFFERENT CHOOLS NTO 11—Shawn Walsh, Maine, 1987-2001 C T D S I 11—Rick Comley, Northern Mich. -

2019-20 Big Ten Hockey Media Guide

2019-20 BIG TEN HOCKEY MEDIA GUIDE BIG LIFE. BIG STAGE. BIG TEN. TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS THE BIG TEN CONFERENCE Media Information ........................................................................................... 2 Headquarters and Conference Center 5440 Park Place • Rosemont, IL 60018 • Phone: 847-696-1010 Big Ten Conference History .............................................................................. 3 New York City Office 900 Third Avenue, 36th Floor • New York, NY, 10022 • Phone: 212-243-3290 Commissioner James E. Delany ........................................................................ 4 Web Site: bigten.org Big Life. Big Stage. Big Ten. ............................................................................... 5 Facebook: /BigTenConference Twitter: @BigTen, @B1GHockey 2019-20 Composite Schedule ........................................................................ 6-7 BIG TEN STAFF – ROSEMONT 2019-20 TEAM CAPSULES........................................................................8-15 Commissioner: James E. Delany Michigan Wolverines ..................................................................... 9 Deputy Commissioner, COO: Brad Traviolia Michigan State Spartans .............................................................. 10 Deputy Commissioner, Public Affairs:Diane Dietz Minnesota Golden Gophers ........................................................ 11 Senior Associate Commissioner, Television Administration:Mark D. Rudner Associate Commissioner, CFO: Julie Suderman Notre Dame Fighting -

HCA December 2010.Indd

Hockey Commissioners’ Association For Immediate Release: Contacts: January 6, 2011 Tim Connor, University of Notre Dame, (574) 631-7519 Dave Moross, Colorado College (719) 389-6755 Fred Pletsch, CCHA, (248) 888-0600 Doug Spencer, WCHA, (608) 829-0100 TYLER JOHNSON OF COLORADO COLLEGE NAMED NATIONAL COLLEGE HOCKEY PLAYER OF THE MONTH Anders Lee of Notre Dame is the Commissioners’ Choice Rookie of the Month FARMINGTON HILLS, Mich. – Colorado College senior forward Tyler Johnson is the Hockey Commissioners’ Association National Division I Player of the Month for December. The 5-foot-9, 170-pound forward helped lead the Tigers to a 6-2-0 run during December by scoring seven goals and adding seven assists, while boasting a +6 rating. He has also recorded the game-winning goal in Colorado College’s last four victories. Johnson added two power-play goals in the month of December, which upped his nation-leading total to nine goals scored with the man advantage. At the midway point of the season, Johnson has already tied his career- high totals which he set in the 2009-10 campaign, posting a 14-9-23 line. He sits in a tie for second place in the WCHA with 14 goals this season. The Cloquet, Minn., native recorded three points (1g, 2a) in a 5-4 victory over Michigan State in the semifi nals of the Great Lakes Invitational, his sixth multi-point game out of a possible eight in December. The Tigers dropped a 6-5 decision to No. 10 Michigan in the GLI championship contest, but Johnson tallied a power- play goal and an assist. -

MSU Blue Line Club Supporting Spartan Hockey Since 1962 NEWSLETTER • VOL

MSU Blue Line Club Supporting Spartan Hockey Since 1962 NEWSLETTER • VOL. 1, 2016-17 Young Spartans Gain Confidence as Big Ten Play Begins By Neil Koepke MSUSpartans.com When Michigan State opened the college hockey season in mid-October, there were a myriad of questions to be answered about the direction of the new-look Spartans. How would MSU replace graduated standout goaltender Jake Hildebrand? Where would the scoring come from? And how would the Spartans respond with 10 freshmen on the roster and most playing key roles? Two months into the season, after experiencing the usual growing pains and some low and high moments, the answers to the prominent questions are starting to come. For sure, it’s taken some time for Michigan State to come together as a team and get its game in sync. But it’s apparent forward Villiam Haag. that there has been steady improvement, and that the skill Minney started the season sharing the goaltending duties level of this team is higher than in recent seasons. with freshman John Lethemon. In the first seven games, Min- The low moment of the season was the opening weekend ney made four starts and Lethemon three. when the Spartans got swept at Lake Superior State, 6-1, 7-3. Minney showed steady improvement and he was rewarded Ouch! That was misery for the players, coaches and fans. with both starts against Ferris State – a home loss and crucial Steady improvement followed, and despite some disap- road win – and played at a high level against North Dakota. pointing losses, Michigan State showed it was more competi- For two seasons playing behind Hildebrand, an NCAA West tive, and several players elevated their game. -

Coaching Records

Coaching Records Coaching Facts .......................................................................... 40 Team-By-Team Won-Lost-Tied Records, By Coach .................................................................................. 41 All-Time Coaches ...................................................................... 44 40 COACHING FACTS Coaching Facts *Does not include vacated years. COACHED TWO DIFFERENT SCHOOLS FROZEN FOUR WINS TOURNAMENT APPEARANCES INTO TOURNAMENT 16—Vic Heyliger, Michigan, 1948-57 (.800) 24—Jack Parker, Boston U., 1974-2012 Ned Harkness, Rensselaer (1953-61) and Cornell 14—*Murray Armstrong, Denver, 1958-72 (.700) 22—Ron Mason, Bowling Green and Michigan St., (1967-70) 14—Jerry York, Bowling Green and Boston College, 1977-2002 Al Renfrew, Michigan Tech (1956) and Michigan 1984-2012 (.700) 22—Red Berenson, Michigan, 1991-2012 (1962-64) 12—Jack Parker, Boston U., 1974-2009 (.522) 20—Jerry York, Bowling Green and Boston College, Len Ceglarski, Clarkson (1962-70) and Boston College 10—John MacInnes, Michigan Tech, 1960-81 (.556) 1982-2013 (1973-91) 9—Ned Harkness, Rensselaer and Cornell, 1953-70 18—Richard Umile, New Hampshire, 1992-2013 Ron Mason, Bowling Green (1977-79) and Michigan St. (.643) (1982-2002) 15—Don Lucia, Colorado Col. and Minnesota, 1995-2013 9—Bob Johnson, Wisconsin, 1970-82 (.643) Jeff Sauer, Colorado Col. (1978) and Wisconsin 8—Gino Gasparini, North Dakota, 1979-87 (.800) 13—Len Ceglarski, Clarkson and Boston College, 1962-91 (1983-2001) 13—George Gwozdecky, Miami (OH) and Denver, 1993- 7—Herb Brooks, Minnesota, 1974-79 (.875) 2013 Mike McShane, St. Lawrence (1983) and Providence 6—Len Ceglarski, Clarkson and Boston College, 12—Doug Woog, Minnesota, 1986-97 (1989-91) 1962-85 (.381) 12—*Jeff Sauer, Colorado Col. and Wisconsin, 1978-2001 George Gwozdecky, Miami (OH) (1993) and Denver 6—Shawn Walsh, Maine, 1988-2000 (.500) (1995-2013) 11—Shawn Walsh, Maine, 1987-2001 Jerry York, Bowling Green (1982-90) and Boston College FROZEN FOUR WINNING PERCENTAGE 11—Rick Comley, Northern Mich. -

THE NCAA NEWS/June 7,1999

The NCAA Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association June 7,1969, Volume 26 Number 23 Committee CFA will continue studv of I-A play-off on costs 4 The College Football Association Ncinas conceded thcrc was “al- has appointed a committee to con ways a possibility” that changes in maps plan tinue studying a proposed 16-team the bowl system could negate the In its first meeting, the Special play-off and to evaluate the post- play-off proposal. Committee on Cost Reduction deve- season bowl structure. That translates into money. The loped an action plan that will include In addition, the CFA voted to 24 CFA teams that played in bowl six months of research and explora- submit legislation at next January’s games last season received $33.5 tion with a goal of legislation for NCAA Convention that would re- million. Revenue from the proposed consideration at the 1991 NCAA store the 30 initial grants per year play-off has been estimated at any- Convention. limit on football grants-in-aid (the where from %42million to $87 mil- The special committee, which current limit is 25). But the CFA lion, with all CFA members sharing was established by the adoption of members rejected a “recovery” plan the money. Proposal No. 39- 1 at the 1989 that would have allowed Division (See rehted story on page 4.) Convention, met May 30 to June 1 I-A schools under the limit to get Donnie Duncan, athletics director in Dallas. back to 95 total scholarships over a at the University of Oklahoma, said The resolution contained in Pro- two-year period. -

Spartan Hockey History 2014-15 Michigan State University Hockey 145 Spartan Hockey History Msuspartans.Com

SPARTAN HOCKEY HISTORY 2014-15 MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY HOCKEY 145 SPARTAN HOCKEY HISTORY MSUSPARTANS.COM SPARTAN HOCKEY TIMELINE OF TRADITION Michigan State has long been at the forefront of collegiate hockey success. Spartan hockey ranks among the winningest programs in NCAA history, and both teams and players alike have reached the pinnacle of achieve- ment. From its championship tradition to record-setting players and coaches, Spartan hockey truly embodies a Commitment to Excellence. Jan. 11, 1922 – Michigan State March 16, 1967 – MSU, fifth in the WCHA regular season, de- plays its first intercollegiate hock- feats champion Michigan Tech, 2-1 in overtime, to win the ey game, falling to Michigan, 5-1. playoffs for the second straight season. Doug Volmar nets both goals, including the winner at 5:44 of overtime. Feb. 11, 1923 – MSU gets its first win, 6-1 over the Lansing March 18, 1967 – After falling to Boston University in the Independents. NCAA semifinals, MSU captures third place with a 6-1 win over North Dakota in the NCAA consolation game. Jan. 12, 1950 – MSU plays its first game since 1930, losing to Nov. 10, 1973 – Tom Ross ties the school record with five Michigan Tech, 6-2. goals in a 9-5 win over Notre Dame at MSU Ice Arena. Nov. 29, 1951 – MSU plays its Dec. 28, 1973 – MSU wins its first Great Lakes Invitational, first game under legendary defeating Michigan Tech, 5-4, in the finals. coach Amo Bessone, defeating Carl Moore played on MSU’s first Ontario Agricultural College, team in 1922, and captained the Oct. -

Men's and Women's Ice Hockey

The Official 2007 NCAA OFFICIAL 2007 NCAA® MEN’S AND WOMEN’S ICE HOCKEY The NCAA salutes the more than RECORDS BOOK 360,000 student-athletes participating in 23 sports at ® Men’s and Women’s Ice Hockey Records Book and Women’s Men’s more than 1,000 member institutions NCAA 55595-10/06 IHR 06 THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 6222, Indianapolis, Indiana 46206-6222 317/917-6222 www.NCAA.org Photo by Saint Anselm Sports Information www.NCAAsports.com Compiled By: J.D. Hamilton, Assistant Director of Statistics. Bonnie Senappe, Assistant Director of Statistics. Jeff Williams, Assistant Director of Statistics. Distributed to sports information directors and conference publicity directors. NCAA, NCAA logo and National Collegiate Athletic Association are registered marks of the Association and use in any manner is prohibited unless prior approval is obtained from the Association. Copyright, 2006, by the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Printed in the United States of America. ISSN 1089-0092 Front Cover Photos (all rows left to right) Top Row: Amy Statz, Wisconsin-Stevens Point; Bill McCurdy, New Hampshire; Cory Schneider and Mike Brennan, Boston College and Robbie Earl, Wisconsin; Richie Fuld, Middlebury. Second Row: Aaron Johnson, Augsburg; Mark Johnson, Wisconsin; John Rolli, Massachusetts-Dartmouth; Bill Mandigo, Middlebury. Third Row: Krissy Wendell, Minnesota; Brett Sterling, Colorado College; Laura Hurd, Elmira; Ron Mason, Michigan State. Bottom Row: Brian Elliott, Wisconsin; Justin Mercier (16) and Head Coach Enrico Blasi, Miami (Ohio); Nikki Burish, Wisconsin; Randi Dumont, Erika Nakamura, Gloria Velez, Shannon Sylvester, Middlebury. 2 2007 NCAA ICE HOCKEY Contents School Name-Change/Abbreviation Key............ -

2.Coaches 13-22 Indd.Indd

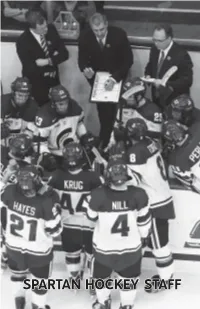

SSPARTANPARTAN HHOCKEYOCKEY SSTAFFTAFF 1133 SPARTAN HOCKEY | 1966, 1986, 2007 NCAA CHAMPIONS HHEADEAD CCOACHOACH TTOMOM AANASTOSNASTOS THE ANASTOS FILE ... EducaƟ on: B.A., Michigan State (1987) Collegiate Playing Experience: Four-year le erwinner, Michigan State (1982-85) Collegiate Coaching Experience: Head Coach, University of Michigan-Dearborn, 1987-90 Assistant Coach Michigan State University , 1990-92 Head Coach Michigan State University, 2011-pres. Head Coaching Records: University of Michigan-Dearborn 68-37-7 (three seasons) Michigan State University 19-16-4 (one season) 1144 SPARTAN HOCKEY | 1966, 1986, 2007 NCAA CHAMPIONS Tom Anastos, a Michigan State alumnus who has stature in college hockey of his alma mater, where excelled in the sport of hockey as a player, coach, he will guide the Spartans into their 72nd varsity administrator, and visionary, was appointed to the season. He will also be helping Michigan State into posi on of Head Coach of the Michigan State Hockey the Big Ten Hockey Conference, which will begin play program on March 23, 2011. Anastos, who previously with the 2013-14 season. served as the commissioner of the Central Collegiate Anastos, who was honored as MSU’s “Distin- Hockey Associa on for 13 seasons, became just the guished Spartan” by the hockey program in 2004, sixth Michigan State hockey coach in program history both played and coached at his alma mater before and the fourth in the modern era. stepping into an administra ve role. He was a four- Anastos’ fi rst season behind the bench (2011-12) year le erwinner at Michigan State (1981-85) for featured an experience-laden team with nine seniors former coach Ron Mason, and received his bachelor’s and 14 upperclassmen overall. -

Approved 2-23-16 MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY COUNCIL MINUTES INTERNATIONAL CENTER, ROOM 115 JANUARY 26, 2016

Approved 2-23-16 MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY COUNCIL MINUTES INTERNATIONAL CENTER, ROOM 115 JANUARY 26, 2016 - 3:15-5:00 P.M. Present: R. Abramovitch, K. Millenbah (for D. Buhler), M. Chaddock (for J. Baker), K. Prouty (for K. Bartig, J. Bell, Y. Bolumole, N. Bunge, G. Burns, J. Carter-Johnson, B. Chakrani, G. Chao, M. Chavez, S.H. Choi, J. Christensen, D. Clemons, M. Crimp, M. Dease, R.K. Edozie, K. Elliot, J. Farley, B. Feltman, R. Floden, M. Floer, M. Kroth (for J. Forger), C. Gall, T. Gates, C. Hogan (for L. Goldstein), G. O’Mura (for S. Gupta, C. Haka, S. Hanson, G. Harrell, E. Helsen, H. Hong, G. Hopenstand, C. Alsup (for J. Howarth, E. Hunter, R. German (for Jackson-Elmore), S. Jaksa, A. Jamison, D. Jordan, A. Kalis, A. Kepsel, R.J. Kirkpatric,, D. Kramer, N. Lafferty, A. Lazarow, J. Litten, C. Long, R. Maleczka, R. Manderfield, J. Maurer, B. Mavis, E. McCallum, R. Miller, E. Moore, D. Nails, M. Nair, M. Noel, S. Noffsinger, J. Palac, M. Piper, S. Printy, R. Rasch, M. Raven, A. Reed, D. Rivera, L. Robinson, J. Rosa, S. Sankar, L. Santavicca, R. LaDuca (for E. Simmons), K. Sims, C. Smith, L. Sochay, A. Sousa, W. Spielman, R. Spiro, B. Sternquist, M. Sticklen, J. Stoddart, W. Strampel, J. Torrez, G. Urquhart, M. Worden, S. Yoder, B. Zandstra Absent: W. Anderson, M. Booth, P. David, J. Dulebohn, S. Esquith, J. Ewing, R. Fernandez, G. Fink, J. Fitzsimmons, J. Francese, S. Garnett, T. Glasmacher, J. Goddeeris, D. Grooms, L. Harris, J.