Mclachlin's Law: in All Its Complex Majesty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youth Activity Book (PDF)

Supreme Court of Canada Youth Activity Book Photos Philippe Landreville, photographer Library and Archives Canada JU5-24/2016E-PDF 978-0-660-06964-7 Supreme Court of Canada, 2019 Hello! My name is Amicus. Welcome to the Supreme Court of Canada. I will be guiding you through this activity book, which is a fun-filled way for you to learn about the role of the Supreme Court of Canada in the Canadian judicial system. I am very proud to have been chosen to represent the highest court in the country. The owl is a good ambassador for the Supreme Court because it symbolizes wisdom and learning and because it is an animal that lives in Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada stands at the top of the Canadian judicial system and is therefore Canada’s highest court. This means that its decisions are final. The cases heard by the Supreme Court of Canada are those that raise questions of public importance or important questions of law. It is time for you to test your knowledge while learning some very cool facts about Canada’s highest court. 1 Colour the official crest of the Supreme Court of Canada! The crest of the Supreme Court is inlaid in the centre of the marble floor of the Grand Entrance Hall. It consists of the letters S and C encircled by a garland of leaves and was designed by Ernest Cormier, the building’s architect. 2 Let’s play detective: Find the words and use the remaining letters to find a hidden phrase. The crest of the Supreme Court is inlaid in the centre of the marble floor of the Grand Entrance Hall. -

For Immediate Release – June 19, 2020 the ADVOCATES' SOCIETY

For immediate release – June 19, 2020 THE ADVOCATES’ SOCIETY ESTABLISHES THE MODERN ADVOCACY TASK FORCE The Advocates’ Society has established a Modern Advocacy Task Force to make recommendations for the reform of the Canadian justice system. The recommendations of the Task Force will seek to combine the best measures by which Canadian courts have adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic with other measures designed to ensure meaningful and substantive access to justice for the long term. The Advocates’ Society believes that permanent changes to our justice system require careful research, analysis, consultation, and deliberation. “This is a pivotal moment for the Canadian justice system,” said Guy Pratte, incoming President of The Advocates’ Society. “There is no doubt that we are learning a great deal from the changes to the system brought about by necessity during this crisis. We have a unique opportunity to reflect on this experience and use it to enhance the efficiency and quality of the justice system. We must do that while preserving the fundamental right of litigants to have their cases put forward in a meaningful and direct way before courts and other decision-makers.” The Task Force is composed of members of The Advocates’ Society from across the country. They will be guided by an advisory panel of some of the most respected jurists and counsel in our country. The Task Force’s mandate is to provide insight and analysis to assist in the modernization of the justice system. It will be informed by experience, jurisprudence and Canadian societal norms. The Task Force will offer recommendations designed to ensure that the Canadian legal system provides a sustainable, accessible and transparent system of justice in which litigants and the public have confidence. -

Rt. Hon. Beverley Mclachlin, P.C. Chief Justice of Canada

Published July 2014 Judicial Profile by Witold Tymowski Rt. Hon. Beverley McLachlin, P.C. Chief Justice of Canada here is little in the early life of Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin that would foreshadow her rise to the highest judicial office in Canada. After all, she was not raised in a large cosmopolitan center, but on a modest Tranch on the outskirts of Pincher Creek, Alberta, a small town in the lee of Canada’s beautiful Rocky Mountains. Her parents, Eleanora Kruschell and Ernest Gietz, did not come from wealth and privilege. They were hard- working ranchers who also took care of a nearby sawmill. Chief Justice McLachlin readily admits that growing up, she had no professional female role models. And so, becoming a lawyer, let alone a judge, was never part of her early career plans. Indeed, the expectation at the time was that women would marry and remain within the home. Girls might aspire to teaching, nursing, or secretarial work, but usually only for a short time before they married. Her childhood, nonetheless, had a distinct influence on her eventual career path. Chief Justice McLachlin proudly refers to herself as a farm girl and has often spoken of a deep affection for Pincher Creek. A Robert McInnes painting depicting a serene pastoral scene, appropriately entitled Pincher Creek, occupies a prominent place in her Supreme Court office and offers a reminder of her humble beginnings. That Chief Justice McLachlin maintains a deep connec- tion with her birthplace is hardly surprising. Despite its geographical remoteness, it nurtured its youth with a It grounded her with a common-sense practicality and culture centered on literacy, hard work, and self-reli- the importance of doing your honest best at whatever ance. -

Nomination a La Cour Supreme Du Canada: L'honorable Juge Thomas A

Nomination 'a la Cour supreme du Canada: L'honorable Juge Thomas A. Cromwell Supreme Court of Canada Appointment: The Honourable Justice Thomas A. Cromwell Les juges ie ]a Cour supreme du Canada et les The judges of the Supreme Court of Canada and membres de la Facult6 de droit de l'Universit6 the University of Ottawa's Faculty of Law have d'Ottawa entretiennent depuis fort longtemps always maintained close personal and profes- d~jA d'6troites relations. La tradition veut que sional ties. It is tradition to hold a welcoming chaque nouveau juge nomm A.la Cour supreme reception for each newly appointed judge to the du Canada soit invit6 A une reception pour Supreme Court of Canada. The Chiel Justice c61bbrer sa nomination. La juge en chef et les and Puisne Judges of the Supreme Court of 2009 CanLIIDocs 61 juges pun~s de la Cour supreme du Canada, les Canada, Deans of the Common Law and Civil doyens des Sections de common law et de droit Law Sections, professors and students are invit- civil de mme que les professeurs et les 6tudi- ed to attend. ants sont toutes et tous convi~s Ay assister. In keeping with this tradition, the Faculty of law Le 26 mars 2009, la Facult6 a de nouveau per- celebrated on March 26, 2009 the appointment pttu6 la tradition, en offrant une r~ception pour of Justice Thomas A. Cromwell, which was [a nomination du juge Thomas A. Cromwell, announced December 22, 2008. As in previous annonce le 22 d~cembre 2008. Tout comme ceremonies for Justices Deschamps, Fish, lors des cArtmonies d'accueil des juges Abella, Charron and Rothstein, the Right Deschamps, Fish, Abella, Charron et Rothstein, Honourable Madam Chief justice Beverley la tr~s honorable juge en chef Beverley McLachlin made introductory remarks and McLachlin a salu6 le ju~e Cromwell. -

695 Legal Writing: Some Tools

LEGAL WRITING: SOME TOOLS 695 LEGAL WRITING: SOME TOOLS THE RIGHT HONOURABLEBEVERLEY MCLACHLIN• I am both honoured and delighted to speak here this evening. First because this address brings me back to my home province of Alberta, and second because it gives me the opportunity to recognize the Alberta Law Review and those who have contributed to its success. Like its companion publications across Canada, the Review is a vital source of analysis of the complex issues facing our legal system. The Review enhances the quality of justice in this country by contributing to a reasoned analysis of these issues. And beyond its legal analysis, the Review gives scholars the chance to write and publish and offers students the opportunity to hone their research, analytical, and writing skills. Tonight I would like to talk to you about the last of these skills - the skill of legal writing. I begin with a preliminary question: Does legal writing still matter in the electronic age? The answer, it seems to me, is an unequivocal yes. The law students here tonight have grown up in the information and communication age. In your lifetimes, computers have become part of the fabric of the workplace. Fax machines hastened the flow of information around the globe, only to be superseded by the everi more powerful technologies of the Internet. Cell phones ring almost everywhere and at any time. These advances in technology and communications have brought us many benefits, speed being the most evident. But we cannot rely on communications technology to ensure the quality of communication. -

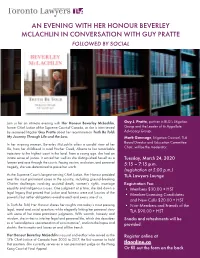

An Evening with Her Honour Beverley Mclachlin in Conversation with Guy Pratte Followed by Social

AN EVENING WITH HER HONOUR BEVERLEY MCLACHLIN IN CONVERSATION WITH GUY PRATTE FOLLOWED BY SOCIAL Join us for an intimate evening with Her Honour Beverley McLachlin, Guy J. Pratte, partner in BLG’s Litigation former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, as she is interviewed Group and the Leader of its Appellate by seasoned litigator Guy Pratte about her recent memoir Truth Be Told: Advocacy Group. My Journey Through Life and the Law. Mark Gannage, Litigation Counsel, TLA Board Director and Education Committee In her inspiring memoir, Beverley McLachlin offers a candid view of her life, from her childhood in rural Pincher Creek, Alberta to her remarkable Chair, will be the moderator. trajectory to the highest court in the land. From a young age, she had an innate sense of justice. It served her well as she distinguished herself as a Tuesday, March 24, 2020 lawyer and rose through the courts. Facing sexism, exclusion, and personal 5:15 – 7:15 p.m. tragedy, she was determined to prove her worth. (registration at 5:00 p.m.) As the Supreme Court’s longest-serving Chief Justice, Her Honour presided TLA Lawyers Lounge over the most prominent cases in the country, including ground-breaking Charter challenges involving assisted death, women’s rights, marriage Registration Fee: equality and indigenous issues. One judgment at a time, she laid down a • Members $30.00 + HST legal legacy that proved that justice and fairness were not luxuries of the • Member Licensing Candidates powerful but rather obligations owed to each and every one of us. -

Donald Marshall, the Supreme Court and Troubles on the Water at Burnt Church

This is the News: Donald Marshall, the Supreme Court and Troubles on the Water at Burnt Church by Paul Fitzgerald A thesis submitted to Saint Mary’s University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Atlantic Canada Studies March 2006, Halifax, Nova Scotia © Paul Fitzgerald Approved: Dr. Chris McCormick External Examinator Kim Kierans Reader Dr. John G. Reid Supervisor March 17, 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-17648-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-17648-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

The Right Honourable Beverley Mclachlin, PC, CC, Cstj

The Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin, PC, CC, CStJ The Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin served as Chief Justice of Canada from 2000 to mid-December 2017. Ms. McLachlin works as an arbitrator and mediator in Canada and internationally. She brings to those forms of dispute resolution her broad and deep experience from over 35 years in deciding a wide range of business law and public law disputes, in both common law and civil law; her ability to work in both English and French; and her experience and skill in leading and consensus-building for many years as the head of a diverse nine- member court. Ms. McLachlin also sits as a Justice of Singapore’s International Commercial Court and the Hong Kong Final Court of Appeal. Her judicial career began in 1981 in the province of British Columbia, Canada. She was appointed to the Supreme Court of British Columbia (a court of first instance) later that year and was elevated to the British Columbia Court of Appeal in 1985. She was appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of British Columbia in 1988 and seven months later, she was sworn in as a Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada. Ms. McLachlin is the first and only woman to be Chief Justice of Canada and she is Canada’s longest serving Chief Justice. The former Chief Justice chaired the Canadian Judicial Council, the Advisory Council of the Order of Canada and the Board of Governors of the National Judicial Institute. In June 2018 she was appointed to the Order of Canada as a recipient of its highest accolade, Companion of the Order of Canada. -

International Journal of the Legal Profession Judging Gender

International Journal of the Legal Profession Judging gender: difference and dissent at the Supreme Court of Canada MARIE-CLAIRE BELLEAU* & REBECCA JOHNSON** ABSTRACT Over 25 years ago, Justice Bertha Wilson asked “Will women judges really make a difference?” Taking up her question, we consider the place of difference in gender and judging. Our focus is on those ‘differences of opinion’ between judges that take the form of written and published judicial dissent. We present and interrogate recent statistics about practices of dissent on the Supreme Court of Canada in relation to gender. The statistics are provocative, but do not provide straightforward answers about gender and judging. They do, however, pose new questions, and suggest the importance of better theorizing and exploring the space of dissent. 1. Introductory observations In a controversial 1990 speech, Justice Bertha Wilson, the first woman judge of the Supreme Court oF Canada, posed a question that has occupied many theorists of law: “Will women judges really make a diFFerence?” (Wilson, 1990). With the beneFit oF 25 years with women judges on Canada’s highest court, it is worth returning to Justice Wilson’s question. But in asking about judges, gender and diFFerence, we want to Foreground a particular kind of diFFerence often present For appellate judges: a ‘diFFerence of opinion’. All judges grapple constantly with the unavoidable tension at the heart oF law—a tension between the demands of stability and responsive change (Fitzpatrick, 2001). But the grappling is intensiFied For appellate judges, who bring multiple skills and divergent liFe experiences to bear on a single case. -

Beverley Mclachlin a 'Chief' Inspiration to Women In

FEBRUARY 2018 BEVERLEY MCLACHLIN Cultivating a spirit of Alumni prepare A ‘CHIEF’ INSPIRATION student engagement and mooters for upcoming community involvement competitions TO WOMEN IN LAW See page 28 See page 10 SEE PAGE 14 CONTENTS QUEEN’S LAW COMMUNITY INDEX DEAN’S COUNCIL MEMBERS Class of ’67 Class of ’91 Hayley Pitcher…46–47 Faculty COVER STORY Sheila A. Murray, Law’82 (Com’79) Doug Forsythe, John Samantha Horn Laura Robinson Beverley Baines, 14 Students meet SCC’s longest- Chair Getliffe, Bob Laughton, …36–37 …10–11 Law’73…49 serving Chief Justice President and General Counsel John McKercher, Phil Leonard Rotman…13 Nick Bala, Law’77…33 CI Financial Corp. Quintin…70 Class of ’15 Kevin Banks…26-27 Before retiring as Chief Justice Queen’s Law Reports Online Class of ’92 Arielle Kaplan…5 Art Cockfield, Law’93 of Canada, Beverley McLachlin David Sharpe, Law’95, Vice-Chair is a periodic electronic update of Class of ’69 Brenda MacDonald …53 President and CEO visited Queen’s as the guest of Queen’s Law Reports magazine Robert Milnes…24 …6–7, 42–43 Class of ’16 Christopher Essert Bridging Finance Inc. honour at a public forum and two published by Emma Cotman…67 …8, 10 gatherings with law students. David Allgood, Law’74 (Arts’70) Class of ’72 Class of ’93 Thomas Mack…46–47 Dean Bill Flanagan Past Chair QUEEN’S FACULTY OF LAW Richard Baldwin…26 Gary Clarke…58–59 Jordan Moss…46–47 …6, 9, 14–15, 26,56 Counsel MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS David Wake…9 58–59, 66–67 Dentons Canada LLP Matt Shepherd, Director Class of ’94 Class of ’17 Gail Henderson…14 Macdonald Hall Class of ’76 Claire Kennedy Michael Coleman…72 Mohamed Khimji…4, FEATURES Betty DelBianco, Law’84 Queen’s University 6, 59 Chief Legal & Administrative Officer The Hon. -

Remarks of the Right Honourable Beverley Mclachlin, P.C., Chief

Remarks of the Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin, P.C. Chief Justice of Canada At the Annual Conference of the Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice October 16, 2015 Saskatoon, Saskatchewan 1 Remarks of the Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin, P.C. Chief Justice of Canada At the Annual Conference of the Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice October 16, 2015 Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Introduction Distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen. I am honoured to address you today at this very important event – the first national conference on indigenous law, bringing together judges, lawyers, police and correctional workers. Merci beaucoup de m’avoir si gentiment invitée à venir vous adresser la parole aujourd’hui. I would like to share with you some of my thoughts on a subject dear to me – access to justice – but from a special perspective – the perspective of Aboriginal peoples. We Canadians like to think that we live in a just society. We have a Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a complex and vast edifice of law, a strong legal profession and a respected judiciary. This has not been achieved easily. Only the vision, tenacity and sacrifice of the generations that have preceded us has yielded these results. Yet the task of securing justice for Canadians is not done. Having achieved a justice system that is the envy of many countries, we have come to realize that we face another challenge: ensuring that all Canadians – be they rich or poor, privileged or marginalized – can actually avail themselves of the system. FINAL AS DELIVERED 2 Today, I propose to explore with you three questions: First, why does access to justice matter? Second, what are the barriers to access to justice? And finally, how do we address the cultural barriers that Aboriginal peoples face in accessing the justice system? 1. -

Reconciliation and the Supreme Court: the Opposing Views of Chief Justices Lamer and Mclachlin

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Articles & Book Chapters Faculty Scholarship 2003 Reconciliation and the Supreme Court: The Opposing Views of Chief Justices Lamer and McLachlin Kent McNeil Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Source Publication: Indigenous Law Journal. Volume 2, Issue 1 (2003), p. 1-26. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation McNeil, Kent. "Reconciliation and the Supreme Court: The Opposing Views of Chief Justices Lamer and McLachlin." Indigenous Law Journal 2.1 (2003): 1-26. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. Reconciliation and the Supreme Court: The Opposing Views of Chief Justices Lamer and McLachlin KENT MCNEIL' I INTRODUCTION 2 II CHIEF JUSTICE LAMER'S VIEWS 4 III MCLACHLIN J.'S VIEWS BEFORE SHE BECAME CHIEF JUSTICE 10 IV ANALYSIS OF THESE DIVERGENT VIEWS OF RECONCILIATION 17 V FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS: DELGAMUUKW AND MARSHALL 19 VI CONCLUSION 23 The Supreme Court of Canada has said that Aboriginal rights were recognized and affirmed in the Canadian Constitution in 1982 in order to reconcile Aboriginalpeoples'prior occupation of Canada with the Crown's assertion of sovereignty. However, sharp divisions appeared in the Court in the 1990s over how this reconciliation is to be achieved Chief Justice Lamer, for the majority, understood reconciliation to involve the balancingof Aboriginal rights with the interests of other Canadians.In some situations,he thought this couldjustify the infringement of Aboriginal rights to achieve, for example, economic and regional fairness.