Physiognomy As a Strategy of Persuasion in Early Christian Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wittgenstein's Critical Physiognomy

Nordic Wittgenstein Review 3 (No. 1) 2014 Daniel Wack [email protected] Wittgenstein’s Critical Physiognomy Abstract In saying that meaning is a physiognomy, Wittgenstein invokes a philosophical tradition of critical physiognomy, one that developed in opposition to a scientific physiognomy. The form of a critical physiognomic judgment is one of reasoning that is circular and dynamic, grasping intention, thoughts, and emotions in seeing the expressive movements of bodies in action. In identifying our capacities for meaning with our capacities for physiognomic perception, Wittgenstein develops an understanding of perception and meaning as oriented and structured by our shared practical concerns and needs. For Wittgenstein, critical physiognomy is both fundamental for any meaningful interaction with others and a capacity we cultivate, and so expressive of taste in actions and ways of living. In recognizing how fundamental our capacity for physiognomic perception is to our form of life Wittgenstein inherits and radicalizes a tradition of critical physiognomy that stretches back to Kant and Lessing. Aesthetic experiences such as painting, poetry, and movies can be vital to the cultivation of taste in actions and in ways of living. Introduction “Meaning is a physiognomy.” –Ludwig Wittgenstein (PI, §568) In claiming that meaning is a physiognomy, Wittgenstein appears to call on a discredited pseudo-science with a dubious history of justifying racial prejudice and social discrimination in order to 113 Daniel Wack BY-NC-SA elucidate his understanding of meaning. Physiognomy as a science in the eighteenth and nineteenth century aimed to provide a model of meaning in which outer signs serve as evidence for judgments about inner mental states. -

Physiognomy in Ancient Science and Medicine

Physiognomy Mariska Leunissen The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Introduction Physiognomy(fromthelaterGreek physiognōmia ,whichisacontractionoftheclassicalform physiognōmonia )referstotheancientscienceofdeterminingsomeone’sinnatecharacteronthe basisoftheiroutward,andhenceobservable,bodilyfeatures.Forinstance,Socrates’famous snubnosewasuniversallyinterpretedbyancientphysiognomistsasaphysiognomicalsignof hisinnatelustfulness,whichheonlyovercamethroughphilosophicaltraining.Thediscipline initstechnicalformwithitsownspecializedpractitionersfirstsurfacesinGreeceinthefifth century BCE ,possiblythroughconnectionswiththeNearEast,wherebodilysignswere takenasindicatorsofsomeone’sfutureratherthanhischaracter.Theshifttocharacter perhapsarisesfromthewidespreadculturalpracticeintheancientGreekandRomanworld oftreatingsomeone’soutwardappearanceasindicativeforhispersonality,whichisalready visibleinHomer(eighthcentury BCE ).Inthe Iliad ,forinstance,adescriptionofThersites’ quarrelsomeandrepulsivecharacterisfollowedbyadescriptionofhisequallyuglybody(see Iliad 2.211–219),suggestingthatthiscorrespondencebetweenbodyandcharacterisno accident.ThersitesisthustheperfectfoilfortheGreekidealofthe kaloskagathos –theman whoisbothbeautifulandgood.Thesameholdsforthepracticeofattributingcharacter traitsassociatedwithaparticularanimalspeciestoapersonbasedonsimilaritiesintheir physique:itisfirstformalizedinphysiognomy,butwasalreadywidelyusedinanon- 1 technicalwayinancientliterature.Themostfamousexampleofthelatterisperhaps SemonidesofAmorgos’satireofwomen(fragment7 -

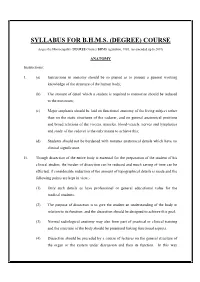

Syllabus for B.H.M.S. (Degree) Course

SYLLABUS FOR B.H.M.S. (DEGREE) COURSE As per the Homoeopathy (DEGREE Course) BHMS regulation, 1983, (as amended up to 2019) ANATOMY Instructions: I. (a) Instructions in anatomy should be so planed as to present a general working knowledge of the structure of the human body; (b) The amount of detail which a student is required to memorise should be reduced to the minimum; (c) Major emphasis should be laid on functional anatomy of the living subject rather than on the static structures of the cadaver, and on general anatomical positions and broad relations of the viscera, muscles, blood-vessels, nerves and lymphatics and study of the cadaver is the only means to achieve this; (d) Students should not be burdened with minutes anatomical details which have no clinical significance. II. Though dissection of the entire body is essential for the preparation of the student of his clinical studies, the burden of dissection can be reduced and much saving of time can be effected, if considerable reduction of the amount of topographical details is made and the following points are kept in view:- (1) Only such details as have professional or general educational value for the medical students. (2) The purpose of dissection is to give the student an understanding of the body in relation to its function, and the dissection should be designed to achieve this goal. (3) Normal radiological anatomy may also form part of practical or clinical training and the structure of the body should be presented linking functional aspects. (4) Dissection should be preceded by a course of lectures on the general structure of the organ or the system under discussion and then its function. -

ARISTOTLE and the IMPORTANCE of VIRTUE in the CONTEXT of the POLITICS and the NICOMACHEAN ETHICS and ITS RELATION to TODAY Kyle Brandon Anthony Bucknell University

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2010 ARISTOTLE AND THE IMPORTANCE OF VIRTUE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE POLITICS AND THE NICOMACHEAN ETHICS AND ITS RELATION TO TODAY Kyle Brandon Anthony Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Anthony, Kyle Brandon, "ARISTOTLE AND THE IMPORTANCE OF VIRTUE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE POLITICS AND THE NICOMACHEAN ETHICS AND ITS RELATION TO TODAY" (2010). Honors Theses. 21. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/21 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 What does it mean to live a good life? 7 The virtuous life 8 Ethical virtue 13 Bravery as an ethical virtue 20 Justice 22 Chapter 2 The Politics and the ideal polis 28 Development of a polis 29 Features of an ideal polis 32 What does it mean to be a citizen of a polis? 40 Aristotle’s views on education 42 Social groups in a polis who are not recognized as citizens 45 Non-ideal political systems 51 Chapter 3 Connections between the Politics and the Ethics 57 Chapter 4 Difficulties in applying Aristotle’s theories to a modern setting 68 Conclusion Where do we go from here? 87 Bibliography 89 iv Acknowledgements First off, I have to thank God, as He helped me endure this project and gave me the courage to press on when I became frustrated, angry, and ready to quit. -

IS GOD in HEAVEN? John Morreall Religion Department the College of William and Mary

IS GOD IN HEAVEN? John Morreall Religion Department The College of William and Mary 1. Introduction t first glance, this question may seem as silly as the quip “Is the Pope Catholic?” For in the Biblical traditions what Ais older and more accepted than the idea that God is in heaven? In his prayer dedicating the temple, Solomon says over and over, “Hear in heaven your dwelling place (I Kings 8:30, 32, 34, 36, 39, 43, 45, 49), and many Jewish prayers are addressed to God in heaven. The central prayer of Christians, composed by Jesus, begins, “Our Father, who art in heaven.” Both the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed say that Jesus ascended into heaven, where he is now “seated at the right hand of the Father.” What I will show, however, is that, far from being an obvious truth, the claim that God is in heaven is logically incoherent, and so necessarily false. I will begin by presenting four features of the traditional concept of heaven, two from the Hebrew Bible, and two from the New Testament and early Christianity. All of these features were developed at a time when God was thought of as a physical being. But, I will then argue, once Christians thought of God as nonphysical, the traditional concept of heaven was no longer acceptable. My argument is that: 1. Heaven is a place. 2. Only what is physical is located in a place. 3. God is not physical. 4. So God is not located in a place. 5. So God is not located in heaven. -

Aristotle: Movement and the Structure of Being

Aristotle: Movement and the Structure of Being Author: Mark Sentesy Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2926 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Philosophy ARISTOTLE: MOVEMENT AND THE STRUCTURE OF BEING a dissertation by MARK SENTESY submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 © copyright by MARK SENTESY 2012 Aristotle: Movement and the Structure of Being Mark Sentesy Abstract: This project sets out to answer the following question: what does movement contribute to or change about being according to Aristotle? The first part works through the argument for the existence of movement in the Physics. This argument includes distinctive innovations in the structure of being, notably the simultaneous unity and manyness of being: while material and form are one thing, they are two in being. This makes it possible for Aristotle to argue that movement is not intrinsically related to what is not: what comes to be does not emerge from non‐being, it comes from something that is in a different sense. The second part turns to the Metaphysics to show that and how the lineage of potency and activity the inquiry into movement. A central problem is that activity or actuality, energeia, does not at first seem to be intrinsically related to a completeness or end, telos. With the unity of different senses of being at stake, Aristotle establishes that it is by showing that activity or actuality is movement most of all, and that movement has and is a complete end. -

The Beginnings of Formal Logic: Deduction in Aristotle's Topics Vs

Phronesis 60 (�0�5) �67-309 brill.com/phro The Beginnings of Formal Logic: Deduction in Aristotle’s Topics vs. Prior Analytics Marko Malink Department of Philosophy, New York University, 5 Washington Place, New York, NY 10003. USA [email protected] Abstract It is widely agreed that Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, but not the Topics, marks the begin- ning of formal logic. There is less agreement as to why this is so. What are the distinctive features in virtue of which Aristotle’s discussion of deductions (syllogismoi) qualifies as formal logic in the one treatise but not in the other? To answer this question, I argue that in the Prior Analytics—unlike in the Topics—Aristotle is concerned to make fully explicit all the premisses that are necessary to derive the conclusion in a given deduction. Keywords formal logic – deduction – syllogismos – premiss – Prior Analytics – Topics 1 Introduction It is widely agreed that Aristotle’s Prior Analytics marks the beginning of formal logic.1 Aristotle’s main concern in this treatise is with deductions (syllogismoi). Deductions also play an important role in the Topics, which was written before the Prior Analytics.2 The two treatises start from the same definition of what 1 See e.g. Cornford 1935, 264; Russell 1946, 219; Ross 1949, 29; Bocheński 1956, 74; Allen 2001, 13; Ebert and Nortmann 2007, 106-7; Striker 2009, p. xi. 2 While the chronological order of Aristotle’s works cannot be determined with any certainty, scholars agree that the Topics was written before the Prior Analytics; see Brandis 1835, 252-9; Ross 1939, 251-2; Bocheński 1956, 49-51; Kneale and Kneale 1962, 23-4; Brunschwig 1967, © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���5 | doi �0.��63/�5685�84-��34��86 268 Malink a deduction is (stated in the first chapter of each). -

1 the Aristotelian Method and Aristotelian

1 The Aristotelian Method and Aristotelian Metaphysics TUOMAS E. TAHKO (www.ttahko.net) Published in Patricia Hanna (Ed.), An Anthology of Philosophical Studies (Athens: ATINER), pp. 53-63, 2008. ABSTRACT In this paper I examine what exactly is ‘Aristotelian metaphysics’. My inquiry into Aristotelian metaphysics should not be understood to be so much con- cerned with the details of Aristotle's metaphysics. I am are rather concerned with his methodology of metaphysics, although a lot of the details of his meta- physics survive in contemporary discussion as well. This warrants an investigation into the methodological aspects of Aristotle's metaphysics. The key works that we will be looking at are his Physics, Meta- physics, Categories and De Interpretatione. Perhaps the most crucial features of the Aristotelian method of philosophising are the relationship between sci- ence and metaphysics, and his defence of the principle of non-contradiction (PNC). For Aristotle, natural science is the second philosophy, but this is so only because there is something more fundamental in the world, something that natural science – a science of movement – cannot study. Furthermore, Aristotle demonstrates that metaphysics enters the picture at a fundamental level, as he argues that PNC is a metaphysical rather than a logical principle. The upshot of all this is that the Aristotelian method and his metaphysics are not threatened by modern science, quite the opposite. Moreover, we have in our hands a methodology which is very rigorous indeed and worthwhile for any metaphysician to have a closer look at. 2 My conception of metaphysics is what could be called ‘Aristotelian’, as op- posed to Kantian. -

Metaphysics Translated by W

Aristotle Metaphysics translated by W. D. Ross Book Α 1 All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves; and above all others the sense of sight. For not only with a view to action, but even when we are not going to do anything, we prefer seeing (one might say) to everything else. The reason is that this, most of all the senses, makes us know and brings to light many differences between things. By nature animals are born with the faculty of sensation, and from sensation memory is produced in some of them, though not in others. And therefore the former are more intelligent and apt at learning than those which cannot remember; those which are incapable of hearing sounds are intelligent though they cannot be taught, e.g. the bee, and any other race of animals that may be like it; and those which besides memory have this sense of hearing can be taught. The animals other than man live by appearances and memories, and have but little of connected experience; but the human race lives also by art and reasonings. Now from memory experience is produced in men; for the several memories of the same thing produce finally the capacity for a single experience. And experience seems pretty much like science and art, but really science and art come to men through experience; for ‘experience made art’, as Polus says, ‘but inexperience luck.’ Now art arises when from many notions gained by experience one universal judgement about a class of objects is produced. -

Greco-Roman Legal Analysis: the Topics of Invention

St. John's Law Review Volume 66 Number 1 Volume 66, Winter 1992, Number 1 Article 3 Greco-Roman Legal Analysis: The Topics of Invention Michael Frost Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GRECO-ROMAN LEGAL ANALYSIS: THE TOPICS OF INVENTION MICHAEL FROST* I. INTRODUCTION Despite a wealth of commentary on legal reas6ning and legal logic, modern writers on the subject demonstrate a curious and re- grettable disregard for the close connections between classical Greco-Roman theories of forensic discourse and modern theories of legal reasoning and analysis. Two recent treatises on logic and legal reasoning, Judge Ruggero Aldisert's Logic for Lawyers' and Pro- fessor Steven Burton's An Introduction to Law and Legal Reason- ing,2 are exceptions to this rule. Their treatises fall within a 2,000- year-old tradition of rhetorical analysis and discourse especially designed for lawyers. Beginning with treatises on rhetoric by Aris- totle, Cicero, and Quintilian, philosophers and lawyers have re- peatedly attempted, some more ambitiously than others, to de- scribe and analyze legal reasoning and methodology. Judge Aldisert implicitly acknowledges his participation in this ancient tradition with an epigraph drawn from Cicero's Republic, with his choice of subject matter, and with his use of centuries-old rhetori- cal terminology.3 Professor Burton's approach to legal analysis and argument can also be traced back to ancient rhetorical treatises especially written for the instruction of beginning advocates. -

Aristotle on Sign-Inference and Related Forms Ofargument

12 Introduction degree oflogical sophistication about what is required for one thing to follow from another had been achieved. The authorities whose views are reported by Philodemus wrote to answer the charges of certain unnamed opponents, usually and probably rightly supposed to be Stoics. These opponents draw· on the resources of a logical STUDY I theory, as we can see from the prominent part that is played in their arguments by an appeal to the conditional (auvTJp.p.EvOV). Similarity cannot, they maintain, supply the basis of true conditionals of the Aristotle on Sign-inference and kind required for the Epicureans' inferences to the rion-evident. But instead of dismissing this challenge, as Epicurus' notoriously Related Forms ofArgument contemptuous attitude towards logic might have led us to expect, the Epicureans accept it and attempt· to show that similarity can THOUGH Aristotle was the first to make sign-inference the object give rise to true conditionals of the required strictness. What is oftheoretical reflection, what he left us is less a theory proper than a more, they treat inference by analogy as one of two species of argu sketch of one. Its fullest statement is found in Prior Analytics 2. 27, ment embraced by the method ofsimilarity they defend. The other the last in a sequence offive chapters whose aim is to establish that: is made up of what we should call inductive arguments or, if we .' not only are dialectical and demonstrative syllogisms [auAAoyw,uol] effected construe induction more broadly, an especially prominent special by means of the figures [of the categorical syllogism] but also rhetorical case of inductive argument, viz. -

INTRODUCTION Anthropometry Literally Means the Measurement of Man. It Is Derived from Greek Words, Anrhropos Which Means Man

INTRODUCTION Anthropometry literally means the measurement of man. It is derived from Greek words, anrhropos which means man and metron which means measure. As an early tool of physical anthropology, it has been used for identification, for the purpose of understanding human physical variation. International Encyclopedia of Ergonomics and Human factors (vol. I) narrated that the word Anthropometry was coined by French naturalist Georges Cuvier. In view of the fact that no two individuals are ever alike in all their measurable characters (except perhaps monozygotic twins) and that the later tend to undergo change in varying degrees, hence persons living under different conditions and members of different ethnic groups and the offspring of unions between them frequently present interesting differences in body form and proportions. It is therefore, necessary to have some means of giving quantitative expression to the variations exhibited by such traits. Anthropometry constitutes a means towards this end, The anthropologists are concemed with functional relationships among traits and between traits and the environment. Anthropometry as defined by Juan Comas is a systematized body of techniques for measuring and taking observations on man, his skeleton, the skull, the limbs and trunk etc., as well as the organs, by the most reliable means and scientific methods." HISTORICAL AND EPISTEMOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE The journey of the concept of anthropometry began in the age of early man when they start to fullfill there needs in the pre-historic times. The units of measurement were probably among the earliest tools invented by humankind. It was this concept of measurement which first initiated the ways of comparison between the ecofacts and artifacts, shapes and sizes of inorganic materials like tools and organic materials like plants and animals and later on man began his/her comparison with others in view of morphology, strength of the body, behaviour,etc.