Florida Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (Nas) Tool Kit A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caring for the Infant with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS)

Dandle•LION products provide supportive care for infants with NAS Caring for the Infant with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (2012), nonpharmacologic care strategies should comprise the initial approach to therapy in treating Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. NAS is a self-limiting condition where the primary goal of the care team is to decrease symptoms without extraneous pharmacological and medical intervention. Successful management of neonatal withdrawal symptoms rests on a foundation of supportive care for mother and infant, with active participation from a multi-disciplinary care team. Evidence- based strategies include providing a calm environment with decreased visual and auditory stimuli, promoting sleep for parents and infant, providing positive proprioceptive and tactile sensory input, and maximizing nutrition to promote weight gain. Ideally, infant and family remain together for the duration of the hospital stay in a quiet, protected environment with Therapeutic Positioning Skin Protection Therapeutic Touch Protective Environment medical and psychosocial support that continues beyond hospitalization. The DandleWRAP Stretch is Preventing diaper dermatitis is Infant massage provides babies Swaddled, immersion bathing designed to support irritable, hard- essential to promoting comfort in with a positive tactile experience promotes temperature stability to-console babies. The lightweight, babies with NAS. Frequent stooling that promotes proprioception and creates a relaxing and calm American Academy of Pediatrics (2017). Alternative treatment approach for neonatal Holmes, A., Atwood, E. Whalen, B. Beliveau, J., Jarvis, J., Matulis, J. & Ralston, S. (2016). abstinence syndrome may shorten hospital stay. AAP News. Accessed online September Rooming-in to treat neonatal abstinence syndrome: Improved family-centered care at lower moisture-wicking fabric reduces can change the pH of the baby’s and encourages development experience for irritable babies. -

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Guideline

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome MENU Introduction Incidence and risk factors 1. Risk factors for illicit drug use 2. Risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes 3. Risk factors for neonatal abstinence syndrome Consequences 1. Tobacco 2. Alcohol 3. Amphetamines 4. Cocaine and derivatives 5. Marijuana 6. Opiates 7. Polydrug use Diagnosis 1. Drug use in pregnancy 2. Testing of newborns 3. Diagnosis of withdrawal Interventions 1. Antenatal care a. Treatment of pregnant users of illicit drugs b. Smoking in pregnancy c. Support from caregivers for pregnant women abusing drugs 2. Postnatal care 3. Pharmacological treatment a. Opioid withdrawal: MORPHINE REGIMEN b. Non-opioid CNS depressants: PHENOBARBITONE REGIMEN c. Management of the vomiting baby Discharge The Drug use in pregnancy team Infant protection issues Follow-Up Keypoints References Introduction: Pregnant women using drugs have the same anxieties and expectations as other pregnant women. All women using drugs are entitled to accurate information, and to be treated sensitively in a non-judgmental manner. Maternal illicit drug use is a risk factor for adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes including preterm birth. Infants born to mothers using illicit drugs (and alcohol and tobacco) are at risk of the toxic effects of the drugs both in-utero and ex-utero; adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes related to the poor socioeconomic situations and lifestyle factors associated with illicit drug use; neonatal drug withdrawal; and the subsequent poor outcomes of infants reared in a socioeconomically disadvantaged environment. The Report of the US Preventative Services Task Force 1996 1 and the monograph review by Bell and Lau 2 1995 are used as background for the content of this guideline. -

Neonatal Drug Withdrawal Abstract

Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care CLINICAL REPORT Neonatal Drug Withdrawal Mark L. Hudak, MD, Rosemarie C. Tan, MD,, PhD, THE abstract COMMITTEE ON DRUGS, and THE COMMITTEE ON FETUS AND Maternal use of certain drugs during pregnancy can result in transient NEWBORN neonatal signs consistent with withdrawal or acute toxicity or cause KEY WORDS opioid, methadone, heroin, fentanyl, benzodiazepine, cocaine, sustained signs consistent with a lasting drug effect. In addition, hos- methamphetamine, SSRI, drug withdrawal, neonate, abstinence pitalized infants who are treated with opioids or benzodiazepines to syndrome provide analgesia or sedation may be at risk for manifesting signs ABBREVIATIONS of withdrawal. This statement updates information about the clinical CNS—central nervous system — presentation of infants exposed to intrauterine drugs and the thera- DTO diluted tincture of opium ECMO—extracorporeal membrane oxygenation peutic options for treatment of withdrawal and is expanded to include FDA—Food and Drug Administration evidence-based approaches to the management of the hospitalized in- 5-HIAA—5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid fant who requires weaning from analgesics or sedatives. Pediatrics ICD-9—International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision — – NAS neonatal abstinence syndrome 2012;129:e540 e560 SSRI—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor INTRODUCTION This document is copyrighted and is property of the American fi Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors Use and abuse of drugs, alcohol, and tobacco contribute signi cantly have filed conflict of interest statements with the American to the health burden of society. The 2009 National Survey on Drug Use Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through and Health reported that recent (within the past month) use of illicit a process approved by the Board of Directors. -

Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System: Normal Values for First 3 Days and Weeks 5–6 in Non-Addicted Infantsadd 2802 524

RESEARCH REPORT doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02802.x Finnegan neonatal abstinence scoring system: normal values for first 3 days and weeks 5–6 in non-addicted infantsadd_2802 524..528 Urs Zimmermann-Baer1,2, Ursula Nötzli1, Katharina Rentsch3 & Hans Ulrich Bucher1 Division of Neonatology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland,1 Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital, Kantonsspital Winterthur, Switzerland2 and Institute for Clinical Chemistry, University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland3 ABSTRACT Objective The neonatal abstinence scoring system proposed by Finnegan is used widely in neonatal units to initiate and to guide therapy in babies of opiate-dependent mothers. The purpose of this study was to assess the variability of the scores in newborns and infants not exposed to opiates during the first 3 days of life and during 3 consecutive days in weeks 5 or 6. Patients and methods Healthy neonates born after 34 completed weeks of gestation, whose parents denied opiate consumption and gave informed consent, were included in this observational study.Infants with signs or symptoms of disease or with feeding problems were excluded. A modified scoring system was used every 8 hours during 72 hours by trained nurses; 102 neonates were observed for the first 3 days of life and 26 neonates in weeks 5–6. A meconium sample and a urine sample at weeks 5–6 were stored from all infants to be analysed for drugs when the baby scored high. Given a non-Gaussian distribution the scores were represented as percentiles. Results During the first 3 days of life median scores remained stable at 2 but the variability increased, with the 95th percentile rising from 5.5 on day 1 to 7 on day 2. -

Simplification of the Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System: Retrospective Study of Two Institutions in the USA

Open Access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016176 on 27 September 2017. Downloaded from Simplification of the Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System: retrospective study of two institutions in the USA Enrique Gomez Pomar,1 Loretta P Finnegan,2 Lori Devlin,3 Henrietta Bada,1 Vanessa A Concina,1 Katrina T Ibonia,1 Philip M Westgate4 To cite: Gomez Pomar E, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Finnegan LP, Devlin L, et al. Objective To develop a simplified Finnegan Neonatal Simplification of the Finnegan Abstinence Scoring System (sFNAS) that will highly ► A simplified scoring system (simplified Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring correlate with scores ≥8 and ≥12 in infants being System: retrospective Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System (sFNAS)) is assessed with the FNAS. study of two institutions proposed developed from a large data set and cross- Design, setting and participants This is a in the USA. BMJ Open validated using a database from another institution. retrospective analysis involving 367 patients admitted to 2017;7:e016176. doi:10.1136/ ► Cutoff values are provided for the sFNAS which two level IV neonatal intensive care units with a total of bmjopen-2017-016176 predict the cutoff value. 40 294 observations. Inclusion criteria included neonates ► The retrospective nature of our study requires ► Prepublication history for with gestational age ≥37 0/7 weeks, who are being this paper is available online. prospective validation of the inter-rater reliability of assessed for neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) using To view these files, please visit the sFNAS and also the clinical validity of this tool. -

Practice Resource: CARE of the NEWBORN EXPOSED to SUBSTANCES DURING PREGNANCY

Care of the Newborn Exposed to Substances During Pregnancy Practice Resource for Health Care Providers November 2020 Practice Resource: CARE OF THE NEWBORN EXPOSED TO SUBSTANCES DURING PREGNANCY © 2020 Perinatal Services BC Suggested Citation: Perinatal Services BC. (November 2020). Care of the Newborn Exposed to Substances During Pregnancy: Instructional Manual. Vancouver, BC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced for commercial purposes without prior written permission from Perinatal Services BC. Requests for permission should be directed to: Perinatal Services BC Suite 260 1770 West 7th Avenue Vancouver, BC V6J 4Y6 T: 604-877-2121 F: 604-872-1987 [email protected] www.perinatalservicesbc.ca This manual was designed in partnership by UBC Faculty of Medicine’s Division of Continuing Professional Development (UBC CPD), Perinatal Services BC (PSBC), BC Women’s Hospital & Health Centre (BCW) and Fraser Health. Content in this manual was derived from module 3: Care of the newborn exposed to substances during pregnancy in the online module series, Perinatal Substance Use, available from https://ubccpd.ca/course/perinatal-substance-use Perinatal Services BC Care of the Newborn Exposed to Substances During Pregnancy ii Limitations of Scope Iatrogenic opioid withdrawal: Infants recovering from serious illness who received opioids and sedatives in the hospital may experience symptoms of withdrawal once the drug is discontinued or tapered too quickly. While these infants may benefit from the management strategies discussed in this module, the ESC Care Tool is intended for newborns with prenatal substance exposure. Language A note about gender and sexual orientation terminology: In this module, the terms pregnant women and pregnant individual are used. -

Opioid-Exposed Mother/Baby Dyads & Breastfeeding

BREASTFEEDING MEDICINE Volume 13, Number 4, 2018 Clinical Research ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/bfm.2017.0172 Examination of Hospital, Maternal, and Infant Characteristics Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation Among Opioid-Exposed Mother-Infant Dyads Davida M. Schiff,1,2 Elisha M. Wachman,1 Barbara Philipp,1 Kathleen Joseph,3 Hira Shrestha,1 Elsie M. Taveras,2 and Margaret G.K. Parker1 Abstract Objectives: Among opioid-exposed newborns, breastfeeding is associated with less severe withdrawal signs, yet breastfeeding rates remain low. We determined the extent to which hospital, maternal, and infant characteristics are associated with breastfeeding initiation and continuation among opioid-exposed dyads. Materials and Methods: We examined breastfeeding initiation and continuation until infants’ discharge among opioid-exposed dyads from 2006 to 2016. Among dyads meeting hospital breastfeeding guidelines, we assessed hospital (changes in breastfeeding guidelines and improvement initiatives [using delivery year as a proxy]), maternal (demographics, comorbid conditions, methadone versus buprenorphine treatment, and delivery mode), and infant (gestational age and birth weight) characteristics. We used multivariable logistic regression to examine independent associations of characteristics with breastfeeding initiation and continuation. Results: Among 924 opioid-exposed dyads, 61% (564) met breastfeeding criteria. Overall, 50% (283/564) of dyads initiated and 33% (187/564) continued breastfeeding until discharge. Breastfeeding initiation and con- tinuation rates increased from 38% and 8% in 2006, to 56% and 34% in 2016, respectively. In adjusted models, infants born after reducing restrictions in hospital breastfeeding guidelines and prenatal breastfeeding education (adjusted odds ratio, aOR 2.6 [95% confidence interval, CI 1.5–4.5]) had increased odds of receiving any maternal breast milk versus infants born with earlier hospital policies. -

Clinical Policy: Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Guidelines Reference Number: CP.MP.86 Revision Log Date of Last Revision: 09/21

CEN,:'ENI;'" ~orporation Clinical Policy: Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Guidelines Reference Number: CP.MP.86 Revision Log Date of Last Revision: 09/21 See Important Reminder at the end of this policy for important regulatory and legal information. Description Maternal drug use and intrauterine exposure of the fetus during pregnancy can lead to drug withdrawal in the infant after delivery. Clinically important neonatal withdrawal most commonly results from intrauterine opioid exposure. However, maternal use of central nervous system depressants (e.g., benzodiazepines, barbiturates and alcohol) and other drugs also results in signs of neonatal symptoms/withdrawal in exposed infants. Neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), describes opioid-only withdrawal symptoms while Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) describes neonates who are at-risk for poly-substance exposure, including opioids. The term NAS will be used here for both polysubstance and opioid-only exposure. Signs of withdrawal will develop in 55 - 94% of neonates exposed to opioids in utero. Typical signs of withdrawal from specific drugs occur based on the half-lives of elimination of the drug. Maternal use of multiple drugs during pregnancy will also have an impact on the onset and severity of NAS. In general though, if one week has elapsed between the last maternal opioid use and delivery, the incidence of NAS is relatively low. Table 1 below lists common drugs abused along with the typical onset of NAS symptoms. Table 1. Common Drug NAS Symptom Onset Drug Typical onset Heroin Within 24 hrs with delay up to 5-7 days or later Methadone 24-72 hrs with delay up to 5-7 days later Morphine & Hydrocodone Within 3 days Buprenorphine Within 40 hrs Ethanol 3-12 hrs Barbiturate 4-7 days with delay up to 14 days Diazepam 12 days Chlordiazepoxide 21 days Policy/Criteria I. -

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Therapeutic Interventions

Juli Sublett, MSN, RN Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Therapeutic Interventions Abstract Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) occurs in infants exposed to opiates or illicit drugs during pregnancy. It can be severe and cause long hospital stays after birth and with symptoms up to 6 months after birth. Pharmaco- logic interventions are commonly used as treatment for NAS; however, their safety and effi cacy are not fully recognized. Pharmacologic treatments for NAS include medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, morphine, and phenobar- bital. Nonpharmacologic interventions and complementary therapies have been documented in neonates. However, there are gaps in the literature regarding use of these thera- pies for neonatal withdrawal. This article provides an overview of the possible risks, benefi ts, and outcomes of pharmacologic and complementary therapies in the neonatal population, and illustrates the gaps in knowledge related to their use for neonatal withdrawal. Keywords: Complementary alternative therapy; Neonatal Absti- nence Syndrome; Pharmacology; Supportive care interventions. Tetra Images/Alamy Tetra 102 volume 38 | number 2 March/April 2013 Copyright © 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. ince the 1980s, the incidence of Neonatal Kaltenbach (2010) refute the idea of gender difference Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) has increased in their research. They state that NAS severity or the by 300% (Backes et al., 2012). NAS is a con- need for treatment is not associated with the sex of the dition in which infants undergo withdrawal infant after performing a large retrospective chart after exposure to prescription or nonprescrip- review of 308 NAS infants. tion opioids such as methadone or heroin in Sutero. -

AWHONN Compendium of Postpartum Care

AWHONN Compendium of Postpartum Care THIRD EDITION AWHONN Compendium of Postpartum Care Third Edition Editors: Patricia D. Suplee, PhD, RNC-OB Jill Janke, PhD, WHNP, RN This Compendium was developed by AWHONN as an informational resource for nursing practice. The Compendium does not define a standard of care, nor is it intended to dictate an exclusive course of management. It presents general methods and techniques of practice that AWHONN believes to be currently and widely viewed as acceptable, based on current research and recognized authorities. Proper care of individual patients may depend on many individual factors to be considered in clinical practice, as well as professional judgment in the techniques described herein. Variations and innovations that are consistent with law and that demonstrably improve the quality of patient care should be encouraged. AWHONN believes the drug classifications and product selection set forth in this text are in accordance with current recommendations and practice at the time of publication. However, in view of ongoing research, changes in government regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to drug therapy and drug reactions, the reader is urged to check information available in other published sources for each drug for potential changes in indications, dosages, warnings, and precautions. This is particularly important when a recommended agent is a new product or drug or an infrequently employed drug. In addition, appropriate medication use may depend on unique factors such as individuals’ health status, other medication use, and other factors that the professional must consider in clinical practice. The information presented here is not designed to define standards of practice for employment, licensure, discipline, legal, or other purposes. -

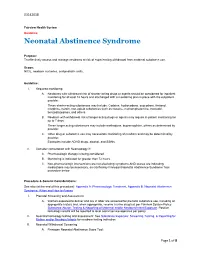

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

03142018 Fairview Health System Guideline Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Purpose: To effectively assess and manage newborns at risk of experiencing withdrawal from maternal substance use. Scope: NICU, newborn nurseries, and pediatric units. Guideline: I. Required monitoring: A. Newborns with withdrawal risk of shorter-acting drugs or agents should be considered for inpatient monitoring for at least 72 hours and discharged with a monitoring plan in place with the outpatient provider. These shorter-acting substances may include: Codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, fentanyl, morphine, heroin, non-opioid substances such as cocaine, methamphetamine, tramadol, benzodiazepines, and others. B. Newborn with withdrawal risk of longer acting drugs or agents may require in-patient monitoring for up to 7 days. These longer acting substances may include methadone, buprenorphine, others as determined by provider. C. Other drug or substance use may necessitate monitoring of newborn and may be determined by provider. Examples include ADHD drugs, alcohol, and SSRIs. II. Consider consultation with Neonatology if: A. Pharmacologic therapy is being considered. B. Monitoring is indicated for greater than 72 hours. C. Non-pharmacologic interventions are not alleviating symptoms AND scores are indicating medications may be necessary, as clarified by Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Tool procedure below. Procedure & General Considerations: See also (at the end of this procedure): Appendix A: Pharmacologic Treatment, Appendix B: Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: When and How to Assess I. Prenatal Screening and Assessment: A. Women expected to deliver and are in labor are screened for prenatal substance use, including an appropriate history and, when appropriate, receive a urine drug test per Fairview System Policy Substance Abuse: Testing & Reporting of Maternal and/or Newborn/Infant Exposure. -

Newborn Payment Policy Applies to the Following Tufts Health Plan Products

Newborn Payment Policy Applies to the following Tufts Health Plan products: ☒ Tufts Health Plan Commercial (including Tufts Health Freedom Plan)1 ☐ Tufts Medicare Preferred HMO (a Medicare Advantage product) ☐ Tufts Health Plan Senior Care Options (SCO) (a dual-eligible product) The following payment policy applies to Tufts Health Plan contracting inpatient facilities and professional providers who render newborn services in an inpatient setting. In addition to the specific information contained in this policy, providers must adhere to the information outlined in the Professional Services and Facilities Payment Policy. Note: Audit and disclaimer information is located at the end of this document. POLICY Tufts Health Plan covers medically necessary well and sick newborn services, in accordance with the member’s benefits and in accordance with federal and applicable state mandate coverage including, but not limited to the provisions of, Chapter 175 Section 47C, Chapter 175 Section 47F and Chapter 176G Section 4. GENERAL BENEFIT INFORMATION Services and subsequent payment are pursuant to the member's benefit plan document. Member eligibility and benefit specifics should be verified prior to initiating services by logging on to the secure Provider website or by contacting Commercial Provider Services. PREVENTIVE SERVICES Due to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (commonly referred to as federal health care reform), with the exception of groups maintaining “grandfathered” status, all Tufts Health Plan products provide 100% coverage for preventive care services. Grandfathered groups are not subject to this requirement, but many have opted to cover preventive services with no cost sharing. This means that most members will have no cost-sharing responsibility when preventive services are rendered by an in-network provider.