Experiencing Azeroth: a Narrative Inquiry Into Playing the Massive Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game (Mmorpg) World of Warcraft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Bobby in Movieland Father Francis J

Xavier University Exhibit Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books Archives and Library Special Collections 1921 Bobby in Movieland Father Francis J. Finn S.J. Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/finn Recommended Citation Finn, Father Francis J. S.J., "Bobby in Movieland" (1921). Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books. Book 6. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/finn/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Library Special Collections at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • • • In perfect good faith Bobby stepped forward, passed the dir ector, saying as he went, "Excuse me, sir,'' and ignoring Comp ton and the "lady" and "gentleman," strode over to the bellhop. -Page 69. BOBBY IN MO VI ELAND BY FRANCIS J. FINN, S.J. Author of "Percy Wynn," "Tom Playfair," " Harry Dee," etc. BENZIGER BROTHERS NEw Yonx:, Cmcnrn.ATI, Cmc.AGO BENZIGER BROTHERS CoPYlUGBT, 1921, BY B:n.NZIGEB BnoTHERS Printed i11 the United States of America. CONTENTS CHAPTER 'PAGB I IN WHICH THE FmsT CHAPTER Is WITHIN A LITTLE OF BEING THE LAST 9 II TENDING TO SHOW THAT MISFOR- TUNES NEVER COME SINGLY • 18 III IT NEVER RAINS BUT IT PouRs • 31 IV MRs. VERNON ALL BUT ABANDONS Ho PE 44 v A NEW WAY OF BREAKING INTO THE M~~ ~ VI Bonny ENDEA vo:r:s TO SH ow THE As TONISHED CoMPTON How TO BE- HAVE 72 VII THE END OF A DAY OF SURPRISES 81 VIII BonnY :MEETS AN ENEMY ON THE BOULEVARD AND A FRIEND IN THE LANTRY STUDIO 92 IX SHOWING THAT IMITATION Is NOT AL WAYS THE SINCEREST FLATTERY, AND RETURNING TO THE MISAD- VENTURES OF BonBY's MoTHER. -

The Videogame Style Guide and Reference Manual

The International Game Journalists Association and Games Press Present THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL DAVID THOMAS KYLE ORLAND SCOTT STEINBERG EDITED BY SCOTT JONES AND SHANA HERTZ THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL All Rights Reserved © 2007 by Power Play Publishing—ISBN 978-1-4303-1305-2 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. Disclaimer The authors of this book have made every reasonable effort to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information contained in the guide. Due to the nature of this work, editorial decisions about proper usage may not reflect specific business or legal uses. Neither the authors nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible to any person or entity with respects to any loss or damages arising from use of this manuscript. FOR WORK-RELATED DISCUSSION, OR TO CONTRIBUTE TO FUTURE STYLE GUIDE UPDATES: WWW.IGJA.ORG TO INSTANTLY REACH 22,000+ GAME JOURNALISTS, OR CUSTOM ONLINE PRESSROOMS: WWW.GAMESPRESS.COM TO ORDER ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL PLEASE VISIT: WWW.GAMESTYLEGUIDE.COM ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our thanks go out to the following people, without whom this book would not be possible: Matteo Bittanti, Brian Crecente, Mia Consalvo, John Davison, Libe Goad, Marc Saltzman, and Dean Takahashi for editorial review and input. Dan Hsu for the foreword. James Brightman for his support. Meghan Gallery for the front cover design. -

Fudge the Elf

1 Fudge The Elf Ken Reid The Laura Maguire collection Published October 2019 All Rights Reserved Sometime in the late nineteen nineties, my daughter Laura, started collecting Fudge books, the creation of the highly individual Ken Reid. The books, the daily strip in 'The Manchester Evening News, had been a part of my childhood. Laura and her brother Adam avidly read the few dog eared volumes I had managed to retain over the years. In 2004 I created a 'Fudge The Elf' website. This brought in many contacts, collectors, individuals trying to find copies of the books, Ken's Son, the illustrator and colourist John Ridgeway, et al. For various reasons I have decided to take the existing website off-line. The PDF faithfully reflects the entire contents of the original website. Should you wish to get in touch with me: [email protected] Best Regards, Peter Maguire, Brussels 2019 2 CONTENTS 4. Ken Reid (1919–1987) 5. Why This Website - Introduction 2004 6. Adventures of Fudge 8. Frolics With Fudge 10. Fudge's Trip To The Moon 12. Fudge And The Dragon 14. Fudge In Bubbleville 16. Fudge In Toffee Town 18. Fudge Turns Detective Savoy Books Editions 20. Fudge And The Dragon 22. Fudge In Bubbleville The Brockhampton Press Ltd 24. The Adventures Of Dilly Duckling Collectors 25. Arthur Gilbert 35. Peter Hansen 36. Anne Wilikinson 37. Les Speakman Colourist And Illustrator 38. John Ridgeway Appendix 39. Ken Reid-The Comic Genius 3 Ken Reid (1919–1987) Ken Reid enjoyed a career as a children's illustrator for more than forty years. -

Theescapist 031.Pdf

In talking further with Alex, I realize he that instance when expectations aren’t It’s the best online mag I’ve ever had didn’t see it coming. He was in design met, when bitterness ensues. Raph the pleasure of reading, and that’s not mode when he made the characters. He suggests that the client is in the hands of just because it’s the only one I’ve read. “It only took us 26 minutes to break it!” thought serpents were powerful and the enemy, and that developers should Well, actually it is ... but it’s still the I said, laughing. Everyone else was quick-striking animals and they made not trust the players. Cory Ondrejka of best! (So cliche). What I love most about laughing, too. Well, everyone except sense as a model for a fighting style. He Linden Lab, the developers of Second the mag is what a lot of others seem to Alex. didn’t expect us to take the martial art in Life has a slightly different take on this enjoy ... the perspective presented by any other way than just that. We idea, as we discovered when Pat Miller your writers and their grasp on the You see, Alex had been tinkering and expected a Friday night of fun, relaxation spoke with him. Also in this issue, Bruce gaming world as a whole. I would have planning for weeks on a new idea for a and laughter. That’s what we made it, Nielson discusses different companies’ to say that my favorite read thus far tabletop game and this was its big debut seeing humor in places it was not policies regarding modders. -

Game Developer Magazine

>> INSIDE: 2007 AUSTIN GDC SHOW PROGRAM SEPTEMBER 2007 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SAVE EARLY, SAVE OFTEN >>THE WILL TO FIGHT >>EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW MAKING SAVE SYSTEMS FOR CHANGING GAME STATES HARVEY SMITH ON PLAYERS, NOT DESIGNERS IN PANDEMIC’S SABOTEUR POLITICS IN GAMES POSTMORTEM: PUZZLEINFINITE INTERACTIVE’S QUEST DISPLAY UNTIL OCTOBER 11, 2007 Using Autodeskodesk® HumanIK® middle-middle- Autodesk® ware, Ubisoftoft MotionBuilder™ grounded ththee software enabled assassin inn his In Assassin’s Creed, th the assassin to 12 centuryy boots Ubisoft used and his run-time-time ® ® fl uidly jump Autodesk 3ds Max environment.nt. software to create from rooftops to a hero character so cobblestone real you can almost streets with ease. feel the coarseness of his tunic. HOW UBISOFT GAVE AN ASSASSIN HIS SOUL. autodesk.com/Games IImmagge cocouru tteesyy of Ubiisofft Autodesk, MotionBuilder, HumanIK and 3ds Max are registered trademarks of Autodesk, Inc., in the USA and/or other countries. All other brand names, product names, or trademarks belong to their respective holders. © 2007 Autodesk, Inc. All rights reserved. []CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2007 VOLUME 14, NUMBER 8 FEATURES 7 SAVING THE DAY: SAVE SYSTEMS IN GAMES Games are designed by designers, naturally, but they’re not designed for designers. Save systems that intentionally limit the pick up and drop enjoyment of a game unnecessarily mar the player’s experience. This case study of save systems sheds some light on what could be done better. By David Sirlin 13 SABOTEUR: THE WILL TO FIGHT 7 Pandemic’s upcoming title SABOTEUR uses dynamic color changes—from vibrant and full, to black and white film noir—to indicate the state of allied resistance in-game. -

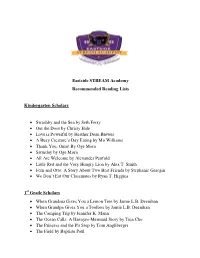

Eastside STREAM Academy Recommended Reading Lists

Eastside STREAM Academy Recommended Reading Lists Kindergarten Scholars Swashby and the Sea by Seth Ferry Out the Door by Christy Hale Love is Powerful by Heather Dean Brewer A Busy Creature’s Day Eating by Mo Williams Thank You, Omu! By Oge Mora Saturday by Oge Mora All Are Welcome by Alexander Penfold Little Red and the Very Hungry Lion by Alex T. Smith Fern and Otto: A Story About Two Best Friends by Stephanie Graegin We Don’t Eat Our Classmates by Ryan T. Higgins 1st Grade Scholars When Grandma Gives You a Lemon Tree by Jamie L.B. Deenihan When Grandpa Gives You a Toolbox by Jamie L.B. Deenihan The Camping Trip by Jennifer K. Mann The Ocean Calls: A Haenyeo Mermaid Story by Tina Cho The Princess and the Pit Stop by Tom Angliberger The Field by Baptiste Paul You Hold Me Up by Monique Gray Smith Dear Dragon: A Pen Pal by Josh Funk It Came in the Mail by Ben Clanton Julian Is a Mermaid by Jessica Love Julian at the Wedding by Jessica Love 2nd Grade Scholars My Papi has a Motorcycle by Isabel Quintero If You Come to Earth by Sophie Blackall Your Name is a Song by Jamilah Thompson Bigelow Norman: One Amazing Goldfish by Kelly Bennett Khalil and Mr. Hagerty and the Backyard Treasures by Tricia Springstubb Ten Ways to Hear Snow by Cathy Camper Giraffe Problems by Jory John The Patchwork Bik by Maxine Beneba Clarke Fruit Bowl by Mark Hoffman Interrupting Chicken and the Elephant of Surprise by David Ezra Jack (Not Jackie) by Erica Silverman I’m New Here by Anne Sibley O’Brien Someone New by Anne Sibley O’Brien 3rd Grade Scholars Pages & Co. -

The New Third Place: Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming in American Youth Culture

Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning Nr 3/2005 Årgång 12 FAKULTETSNÄMNDEN FÖR LÄRARUTBILDNING THE FACULTY BOARD FOR TEACHER EDUCATION Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning nr 3 2005 årgång 12 Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning (fd Lärarutbildning och forskning i Umeå) ges ut av Fakultetsnämnden för lärarutbildning vid Umeå universitet. Syftet med tidskriften är att skapa ett forum för lärarutbildare och andra didaktiskt intresserade, att ge information och bidra till debatt om frågor som gäller lärarutbildning och forskning. I detta avseende är tidskriften att betrakta som en direkt fortsättning på tidskriften Lärarutbildning och forskning i Umeå. Tidskriften välkomnar även manuskript från personer utanför Umeå universitet. Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning beräknas utkomma med fyra nummer per år. Ansvarig utgivare: Dekanus Björn Åstrand Redaktör: Fil.dr Gun-Marie Frånberg, 090/786 62 05, e-post: [email protected] Bildredaktör: Doktorand Eva Skåreus e-post: [email protected] Redaktionskommitté: Docent Håkan Andersson, Pedagogiska institutionen Professor Åsa Bergenheim, Pedagogiskt arbete Docent Per-Olof Erixon, Institutionen för estetiska ämnen Professor Johan Lithner, Matematiska institutionen Doktorand Eva Skåreus, Institutionen för estetiska ämnen Universitetsadjunkt Ingela Valfridsson, Institutionen för moderna språk Professor Gaby Weiner, Pedagogiskt arbete Redaktionens adress: Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning, Gun-Marie Frånberg, Värdegrundscentrum, Umeå universitet, 901 87 UMEÅ. Grafisk formgivning: Eva Skåreus och Tomas Sigurdsson, Institutionen för estetiska ämnen Illustratör: Eva Skåreus Original: Print & Media, Umeå universitet Tryckeri: Danagårds grafiska, 2005:2001107 Tekniska upplysningar till författarna: Tidskrift för lärarutbildning och forskning framställs och redigeras ur allmänt förekommande Mac- och PC-program. Sänd in manuskript på diskett eller som e-postbilaga. -

SUPERGIRLS and WONDER WOMEN: FEMALE REPRESENTATION in WARTIME COMIC BOOKS By

SUPERGIRLS AND WONDER WOMEN: FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN WARTIME COMIC BOOKS by Skyler E. Marker A Master's paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina May, 2017 Approved by: ________________________ Rebecca Vargha Skyler E. Marker. Supergirls and Wonder Women: Female Representation in Wartime Comics. A Master's paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. May, 2017. 70 pages. Advisor: Rebecca Vargha This paper analyzes the representation of women in wartime era comics during World War Two (1941-1945) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (2001-2010). The questions addressed are: In what ways are women represented in WWII era comic books? What ways are they represented in Post 9/11 comic books? How are the representations similar or different? In what ways did the outside war environment influence the depiction of women in these comic books? In what ways did the comic books influence the women in the war outside the comic pages? This research will closely examine two vital periods in the publications of comic books. The World War II era includes the genesis and development to the first war-themed comics. In addition many classic comic characters were introduced during this time period. In the post-9/11 and Operation Iraqi Freedom time period war-themed comics reemerged as the dominant format of comics. Headings: women in popular culture-- United States-- History-- 20th Century Superhero comic books, strips, etc.-- History and criticism World War, 1939-1945-- Women-- United States Iraq war (2003-2011)-- Women-- United States 1 I. -

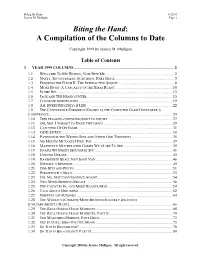

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29 -

Sistema De Controlo De Versões Em Mundos Virtuais Para Negociação De Configurações Espaciais

Sistema de Controlo de Versões em Mundos Virtuais para Negociação de Configurações Espaciais Tese apresentada por Filipe Santos à Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Informática, sob a orientação de Leonel Morgado e de Benjamim Fonseca, Professores Auxiliares do Departamento de Engenharias da Escola de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro. Aos meus pais. i ii AGRADECIMENTOS Numa tese que assenta em modelos de aprendizagem colaborativos, que defendem que a aprendizagem é especialmente significativa quando se dá “com o outro”, não podia deixar o seu autor de agradecer a todo um conjunto de pessoas que, pela sua contribuição através de sugestões, críticas ou revisões, tornaram a sua própria aprendizagem (e, consequentemente, este contributo) significativo. Foram muitas as pessoas que participaram directamente ou indirectamente ao longo deste processo. A todos estou grato. Em particular, gostaria de salientar e agradecer: Aos meus orientadores, Leonel Morgado e Benjamim Fonseca, e ao professor Paulo Martins pela constante orientação e revisão dos textos produzidos ao longo de todo este percurso; Ao Carlos Ferreira, Antónia Barreto e Mafalda Belo pelo seu auxílio nos aspectos científicos ligados às ciências sociais e da educação; Aos dois professores do 1º ciclo do ensino básico, professores Pascal Paulus e Augusta Santos, que me abriram as portas das suas salas de aula e me deixaram conduzir este projecto com as suas turmas e nas suas práticas lectivas. Estou também muito agradecido a todos os “pequenotes” que foram, também eles, participantes nesta fase, fruto de uma pedagogia que os ouve e os toma em consideração nos muitos processos de tomada de decisão; Aos meus pais, Manuel e Elisabete Santos, pela constante paciência, encorajamento e confiança. -

What Is the Future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming? Richard Slater (00804443) What Is the Future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming?

What is the future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming? Richard Slater (00804443) What is the future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming? Richard Slater (00804443) An undergraduate dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of CS335 - The Computing Dissertation module of BSc (Hons) Computer Science. I (Richard Slater) hereby certify that the content of this document has been produced solely by me in person according to the regulations set out by the University of Brighton, as such it is an original work. I so declare that any reference to non-original document or material has been properly acknowledged. Document Data Total Word Count 8944 Word Count 8090 excluding footnotes and annexes Modified 26 February 2004 By Richard Slater Revision 78 a PDF version of this document is available at http://www.richard-slater.co.uk/university/dissertation Page 1 of 28 What is the future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming? Richard Slater (00804443) 1) Table of Contents 1) Table of Contents................................................................................................... 2 2) Abstract................................................................................................................ 3 3) Introduction........................................................................................................... 4 3.1) Terms and Definitions.......................................................................................4 3.2) Quality of references........................................................................................5