The Priority of Morality: the Emergency Constitution's Blind Spot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Frameworks for Detaining Terrorist Suspects

RETHINKING “PREVENTIVE DETENTION” FROM A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE: THREE FRAMEWORKS FOR DETAINING TERRORIST SUSPECTS Stella Burch Elias* ABSTRACT President Barack Obama has convened a multi-agency taskforce whose remit includes considering whether the United States should continue to hold terrorist suspects in extra-territorial “preventive detention,” should develop a new system of “preventive detention” to hold terrorist suspects on domestic soil, or should eschew any use of “preventive detention.” American scholars and advocates who favor the use of “preventive detention” in the United States frequently point to the examples of other countries in support of their argument. At the same time, advocates and scholars opposed to the introduction of such a system also turn to comparative law to bolster their arguments against “preventive detention.” Thus far, however, the scholarship produced by both sides of the debate has been limited in two key respects. Firstly, there have been definitional inconsistencies in the literature—the term “preventive detention” has been used over- broadly to describe a number of different kinds of detention with very little acknowledgment of the fundamental differences between these alternative regimes. Secondly, the debate has been narrow in scope— focusing almost exclusively on “preventive detention” in three or four other (overwhelmingly Anglophone) countries. This Article seeks to * Law Clerk to the Honorable Stephen Reinhardt. Yale Law School, J.D. 2009. I am very grateful to Harold Hongju Koh, Hope Metcalf, Judith Resnik, Reva Siegel, Muneer Ahmad, Sarah Cleveland, and John Ip for their generous advice and thoughtful comments on earlier versions of this article, to Allison Tait, Megan Barnett, and the Yale Law Teaching Series workshop participants for their helpful feedback, and to Meera Shah, Megan Crowley, and the Columbia Human Rights Law Review for their terrific editing. -

VIII. Arbitrary Arrest and Detention

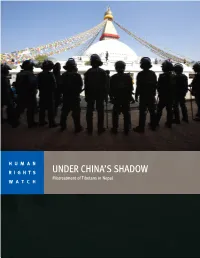

HUMAN RIGHTS UNDER CHINA’S SHADOW Mistreatment of Tibetans in Nepal WATCH Under China’s Shadow Mistreatment of Tibetans in Nepal Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-1135 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2014 978-1-62313-1135 Under China’s Shadow Mistreatment of Tibetans in Nepal Map of Nepal ....................................................................................................................... i Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

Germany 2020 Human Rights Report

GERMANY 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Germany is a constitutional democracy. Citizens choose their representatives periodically in free and fair multiparty elections. The lower chamber of the federal parliament (Bundestag) elects the chancellor as head of the federal government. The second legislative chamber, the Federal Council (Bundesrat), represents the 16 states at the federal level and is composed of members of the state governments. The country’s 16 states exercise considerable autonomy, including over law enforcement and education. Observers considered the national elections for the Bundestag in 2017 to have been free and fair, as were state elections in 2018, 2019, and 2020. Responsibility for internal and border security is shared by the police forces of the 16 states, the Federal Criminal Police Office, and the federal police. The states’ police forces report to their respective interior ministries; the federal police forces report to the Federal Ministry of the Interior. The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and the state offices for the protection of the constitution are responsible for gathering intelligence on threats to domestic order and other security functions. The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution reports to the Federal Ministry of the Interior, and the state offices for the same function report to their respective ministries of the interior. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over security forces. Members of the security forces committed few abuses. Significant human rights issues included: crimes involving violence motivated by anti-Semitism and crimes involving violence targeting members of ethnic or religious minority groups motivated by Islamophobia or other forms of right-wing extremism. -

Preventive Detention Draft 1

Volume 14, No. 1 2010 TOURO INTERNATIONAL LAW REVIEW 128 EXTREME MEASURES: DOES THE UNITED STATES NEED PREVENTIVE DETENTION TO COMBAT DOMESTIC TERRORISM? By Diane Webber Preventive detention: “an extreme measure which places the individual wholly under the control of the state, not as a punishment for a proven transgression of the law but rather as a precautionary measure based on a presumption of actual or future criminal conduct…” 1 ABSTRACT This paper deals with preventive detention in the United States, i.e. the detaining of a suspect to prevent a future domestic terrorist offense. Two recent events are examined: the Fort Hood shootings; and a preventive arrest in France, to consider problems in combating terrorist crimes on U.S. soil. The paper demonstrates that U.S. law as it now stands, with some limited exceptions, does not permit detention to forestall an anticipated domestic terrorist crime. After reviewing and evaluating the way in which France, Israel and the United Kingdom use forms of preventive detention to thwart possible terrorist acts, the paper proposes three possible ways to fill this gap in U.S. law, and give the United States the same tools to fight terrorism as the other countries discussed in the paper, within the boundaries of the Constitution. Diane Webber, Solicitor of the Senior Courts of England and Wales, LL.B. University College London, LL.M. Georgetown University, Candidate for SJD Georgetown University expected completion in 2014. I would like to thank Professor David P. Stewart for all his help and guidance, and my family John Webber, Daniel Webber and Katie Hyman for their unwavering support and encouragement. -

Alternative Report About Torture Situation in Peru by the Group Against Torture of the National Coordinator of Human Rights

ALTERNATIVE REPORT ABOUT TORTURE SITUATION IN PERU BY THE GROUP AGAINST TORTURE OF THE NATIONAL COORDINATOR OF HUMAN RIGHTS I.- Presentation: The National Coordinator of Human Rights (CNDDHH) is a human right’s collective which groups 79 non-governmental organizations dedicated to defend, promote and educate in human Rights in Peru. It is also, an organization with a special consultative status in the Social and Economic Council of United Nations (UN) and is credited to participate in activities of the Organization of American States (OAS). The present report was developed by the Work Group against Torture of the CNDDHH, specifically on behalf of the Executive Secretariat of the CNDDHH, the Episcopal Commission for Social Action (CEAS), the Center for Psychosocial Care (CAPS) and the Human Rights Commission (COMISEDH). This report expects to report the human rights situation in our country, dealing specifically with problems regarding torture, taking as starting point the information delivered, on behalf of the Peruvian State, in the document called: “Sixth Periodical Report that the State parties must present in 2009, submitted in response to the list of issues (CAT/CPER/Q/6) transmitted to the State party pursuant to the optional reporting procedure (A/62/44, paras. 23 and 24). Peru” dated 28 th July 2011. The information delivered will regard issues that the Committee against Torture (CAT) has formulated to the Peruvian State, taking into account the information we have according to the lines of work of each institution which took part developing the present report. II.- Information regarding the Conventions articles ARTÍCLE 2º 1. -

An Analysis of Preventive Detention for Serious Offenders

An Analysis of Preventive Detention for Serious Offenders PETER MARSHALL* I INTRODUCTION Modem societies are increasingly concerned with risk and the management of insecurity. Preventive detention occupies a key role in the penal response. It is difficult to deny that particularly dangerous offenders should be detained for substantial periods until the risk they pose has reduced. Indeed many Western constituencies demand laws providing these powers. However, preventive detention is an extremely serious and invasive intervention, bearing directly on fundamental human rights and civil liberties. It is also an inherently expansionist policy, often driven by fear and alarm.' As such a detailed examination of the complexities with, and objections to, the practice of preventive detention is appropriate. The term "preventive detention" as used in this paper is a general species of sentence defined by three characteristics: it is of indefinite duration; it is targeted at "dangerous" offenders; and it is intended to prevent the offender from causing serious harm in the future. While the term preventive detention is used in New Zealand, the sentence goes by a myriad of aliases in other jurisdictions. As this paper takes a generic focus, a variety of equivalent rather than jurisdiction-specific terms are used to refer to these indefinite sentences for public protection. Discussion of, and objections to, indefinite sentences come from many different fields, including philosophy, ethics, human rights, the medical and predictive sciences, and legal theory. The concerns expressed are serious, but always contested. Although the legitimacy or illegitimacy of preventive detention cannot be determined on the basis of any one set of considerations, all have a role to play in defining the requirements for a justifiable form of this sentence. -

1 Preventive Detention in Europe and the United States © Christopher

Preventive Detention in Europe and the United States © Christopher Slobogin Vanderbilt University Law School Introduction In M. v. Germany,1 decided in 2010, the European Court of Human Rights addressed the legality of indeterminate criminal dispositions based in whole or part on assessments of risk. In more general terms, the case examines the tension between the government’s desire to keep dangerous people off the streets and a convicted offender’s interest in avoiding prolonged confinement based solely on predictions of antisocial behavior. The decisions in this case—from the lower level German courts, through the Federal Constitutional Court in Germany, to the European Court of Human Rights—illustrate a range of approaches to this difficult issue. This paper provides both a discussion of M. v. Germany on its own terms and a comparison of the case with United States law on preventive detention, particularly as laid out in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Kansas v. Hendricks,2 and related sentencing jurisprudence. Read narrowly, the European Court’s decision in M. is consistent with Hendricks. Both cases prohibit indeterminate incarceration based solely on a prediction of future conduct when the incarceration is punitive in nature. Both also appear to allow non-punitive preventive detention, particularly of people with serious mental disorder. Read broadly, however, M.’s definition of “punitive” appears to be different than Hendricks’. Further, the limitations that M. imposes on indefinite detention that occurs in connection with criminal sentencing may be more stringent than those required by American constitutional restrictions on punishment. The European Court’s treatment of preventive detention ends up being both more nuanced and less formalistic than American caselaw, but it stills leaves a number of questions unanswered. -

Limits of Preventive Detention, the Rinat Kitai-Sangero the Academic Center of Law and Business, Israel

McGeorge Law Review Volume 40 | Issue 4 Article 3 1-1-2008 Limits of Preventive Detention, The Rinat Kitai-Sangero The Academic Center of Law and Business, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/mlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Rinat Kitai-Sangero, Limits of Preventive Detention, The, 40 McGeorge L. Rev. (2016). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/mlr/vol40/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Law Reviews at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in McGeorge Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Limits of Preventive Detention Rinat Kitai-Sangero* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRO DUCTION ............................................................................................ 904 II. ARGUMENTS AGAINST THE GROUND OF DANGEROUSNESS ........................ 908 A. The Ability to Predict Dangerousnessand the Elusive Concept of Dangerousness .................................................................................. 908 B. Detention as Punishment ....................................................................... 915 C. A Presumption of G uilt .......................................................................... 920 III. BALANCING THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE AGAINST THE PUBLIC INTEREST IN PREVENTING HARM ................................................................. 923 IV. SETTING LIMITS ON PREVENTIVE DETENTION -

Preventive Detention: a Comparison of Bail Refusal Practices in the United States, England, Canada and Other Common Law Nations

Pace International Law Review Volume 8 Issue 2 Spring 1996 Article 4 April 1996 Preventive Detention: A Comparison of Bail Refusal Practices in the United States, England, Canada and Other Common Law Nations Kurt X. Metzmeier Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr Recommended Citation Kurt X. Metzmeier, Preventive Detention: A Comparison of Bail Refusal Practices in the United States, England, Canada and Other Common Law Nations, 8 Pace Int'l L. Rev. 399 (1996) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr/vol8/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace International Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PREVENTIVE DETENTION: A COMPARISON OF BAIL REFUSAL PRACTICES IN THE UNITED STATES, ENGLAND, CANADA AND OTHER COMMON LAW NATIONS Kurt X. Metzmeiert I. INTRODUCTION With origins obscured in the mists of Anglo-Saxon history, bail as an institution still unites the criminal law systems of England, the United States, Canada and many nations of the former British empire. However, conscious cross-comparison by modern English-speaking legal reformers, rather than blind ad- herence to ancient precedent, has caused many similarities in the countries' legal practices. Examining each others' legal sys- tems, critical articles and treatises, and law reforms, reformers have carried on a debate on bail across national lines that has been written into the law of nations from Canada to New Zea- land. The United States, while not completely part of this dis- cussion, has both contributed to and benefitted from this debate. -

Solitary Confinement and the “Hard” Cases in the United States and Norway

UCLA UCLA Criminal Justice Law Review Title “Everything Is at Stake if Norway Is Sentenced. In that Case, We Have Failed”: Solitary Confinement and the “Hard” Cases in the United States and Norway Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0bv8f638 Journal UCLA Criminal Justice Law Review, 1(1) Author Rovner, Laura Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Solitary Confinement in US and Norway “EVERYTHING IS AT STAKE IF NORWAY IS SENTENCED. IN THAT CASE, WE HAVE FAILED”:* Solitary Confinement and the “Hard” Cases in the United States and Norway Laura Rovner** While the harms caused by solitary confinement and its overuse in American prisons have gained increased recognition over the last decade, most states and the federal government maintain that extensive solitary confinement is both necessary and appropriate for those people deemed “the worst of the worst.” As a result, many of those who have been so la- beled have languished in solitary confinement for years or even decades. With limited exceptions, they are there with the blessing of the federal courts, which have generally held that even very lengthy periods of solitary confinement do not violate the Eighth Amendment’s Cruel and Unusual Punishments clause. In this Article, I examine a Norwegian court’s holding that Anders Behring Breivik’s long-term solitary confinement violates the European Convention on Human Rights to consider the lessons it holds for American Eighth Amendment conditions of confinement jurisprudence. * Wenche Fuglehaug & Andreas Bakke Foss, Everything Is at Stake if Norway Is Sentenced. In That Case We Have Failed, Aftenposten (Feb. -

Administrative Detention

http://assembly.coe.int Doc. 14079 06 June 2016 Administrative detention Report1 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Rapporteur: Lord Richard BALFE, United Kingdom, European Conservatives Group Summary The Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights stresses the importance of the right to liberty and security guaranteed in Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. It is worried that administrative detention has been abused in certain member States for purposes of punishing political opponents, obtaining confessions in the absence of a lawyer and/or under duress, or apparently for stifling peaceful protests. Regarding administrative detention as a tool to prevent terrorism or other threats to national security, the committee recalls that purely preventive detention of persons suspected of intending to commit a criminal offence is not permissible and points out that mere restrictions (as opposed to deprivation) of liberty are permissible in the interests of national security or public safety and for the prevention of crime. All member States concerned should refrain from using administrative detention in violation of Article 5. Instead, they should make use of available tools respecting human rights in order to protect national security or public safety. Giving examples of such tools, the committee recalls their legal requirements, including a prohibition of discrimination on the basis of nationality. 1. Reference to committee: D oc. 12998, Reference 3900 of 1 October 2012. F - 67075 Strasbourg Cedex | [email protected] | Tel: +33 3 88 41 2000 | Fax: +33 3 88 41 2733 Doc. 14079 Report Contents Page A. Draft resolution......................................................................................................................................... 3 B. Explanatory memorandum by Lord Richard Balfe, rapporteur................................................................. -

Measures Aimed at Reducing the Use of Pretrial Detention in the Americas

OEA/Ser.L/V/II.163 Doc. 105 3 July 2017 Original: Spanish INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Report on Measures Aimed at Reducing the Use of Pretrial Detention in the Americas 2017 www.iachr.org OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Rapporteurship on the Rights of Persons Deprived of Liberty. Report on measures aimed at reducing the use of pretrial detention in the Americas. p. ; cm. (OAS. Official records ; OEA/Ser.L/V/II) ISBN 978-0-8270-6663-2 1. Preventive detention--America. 2. Prisoners--Civil rights--America. 3. Pre-trial procedure--America. 4. Criminal procedure--America. 5. Detention of persons--America. 6. Human rights--America. I. Title. II. Series. OEA/Ser.L/V/II.163 Doc. 105 Document published thanks to the financial support of the Spanish Fund for the OAS. The positions herein expressed are those of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of the Spanish Fund for the OAS. INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Members Francisco José Eguiguren Praeli Margarette May Macaulay Esmeralda Arosemena de Troitiño José de Jesús Orozco Henríquez Paulo Vannuchi James L. Cavallaro Luis Ernesto Vargas Silva Executive Secretary Paulo Abrão Assistant Executive Secretary Elizabeth Abi-Mershed The Commission acknowledges the special efforts of its Executive Secretariat in producing this report, and in particular, Sofía Galván Puente, Human Rights Specialist. Approved by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on July 3, 2017. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11 CHAPTER 1 | INTRODUCTION 21 A. Background, Scope, and Purpose of the Report 21 B.