Solid Metaphor and Sacred Space: Interpreting the Paradigmatic and Syntagmatic Relations Found at Beth Alpha Synagogue Evan Carter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

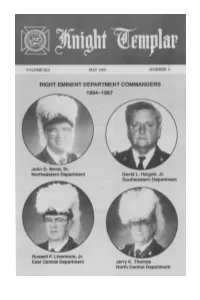

February Has, for a Short Period of Time, Been Designated As the Month of the Year That We Have Set Aside to Honor Those Who Have Served Our Nation As President

Salute to the Masonic Past Presidents of the United States of America February has, for a short period of time, been designated as the month of the year that we have set aside to honor those who have served our nation as President. This tradition began many years ago with the celebration of the birthdays of President George Washington and President Abraham Lincoln in the month of their birthdays. Fourteen of the presidents of the United States of America have been Master Masons and have carried out the true virtues of the Masonic order. They were: George Washington, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, James Polk, James Buchanan, Andrew Johnson, James Garfield, William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, William H. Taft, Warren G. Harding, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S Truman, and Gerald R. Ford. Each has left a legacy to us, to our children, and to our grandchildren that is rich in history and steeped in glory. Many of these Masonic presidents, since George Washington and through Gerald Ford, have served during events in history that make us all proud to be able to call them Brethren. There is another group of Brethren and Sir Knights with whom we are more closely associated. They have served as Presidents of the Knights Templar Eye Foundation since its inception. Sir Knights Walter A. DeLamater, Louis Henry Wieber, Paul Miller Moore, Wilber Marion Brucker, John Lawton Crofts, Sr., George Wilbur Bell, Roy Wilford Riegle, Willard Meredith Avery*, Kenneth Culver Johnson, Ned Eugene Dull, Donald Hinslea Smith, Marvin Edward Fowler, and William Henry Thornley, Jr. Sir Knight Walter A. -

Archaeology in the Holy Land IRON AGE I

AR 342/742: Archaeology in the Holy Land IRON AGE I: Manifest Identities READING: Elizabeth Bloch-Smith and Beth Alpert Nahkhai, "A Landscape Comes to Life: The Iron Age I, " Near Eastern Archaeology 62.2 (1999), pp. 62-92, 101-27; Elizabeth Bloch-Smith, "Israelite Ethnicity in Iron I: Archaeology Preserves What is Remembered and What is Forgotten in Israel's History," Journal of Biblical Literature 122/3 (2003), pp. 401-25. Wed. Sept. 7th Background: The Territory and the Neighborhood Fri. Sept. 9th The Egyptian New Kingdom Mon. Sept. 12th The Canaanites: Dan, Megiddo, & Lachish Wed. Sept. 14th The Philistines, part 1: Tel Miqne/Ekron & Ashkelon Fri. Sept. 16th The Philistines, part 2: Tel Qasile and Dor Mon. Sept. 19th The Israelites, part 1: 'Izbet Sartah Wed. Sept. 21st The Israelites, part 2: Mt. Ebal and the Bull Site Fri. Sept. 23rd Discussion day & short paper #1 due IRON AGE II: Nations and Narratives READING: Larry Herr, "The Iron Age II Period: Emerging Nations," Biblical Archaeologist 60.3 (1997), pp. 114-83; Seymour Gitin, "The Philistines: Neighbors of the Canaanites, Phoenicians, and Israelites," 100 Years of American Archaeology in the Middle East, D. R. Clark and V. H. Matthews, eds. (American Schools of Oriental Research, Boston: 2004), pp. 57-85; Judges 13:24-16:31; Steven Weitzman, "The Samson Story as Border Fiction," Biblical Interpretation 10,2 (2002), pp. 158-74; Azzan Yadin, "Goliath's Armor and Israelite Collective Memory," Vetus Testamentum 54.3 (2004), pp. 373-95. Mon. Sept. 26th The 10th century, part 1: Hazor and Gezer Wed. -

The Wofford Israel Trip Leaves on Friday, January 6, on a 15 Hour Flight from GSP, Through New York, and to Tel Aviv

Wofford's Israel Trip JANUARY 01, 2006 ISRAEL BOUND on JANUARY 6! The Wofford Israel trip leaves on Friday, January 6, on a 15 hour flight from GSP, through New York, and to Tel Aviv. With the 7 hour time difference, it will "seem" like a 22 hour flight. If you thought sitting through an 80' lecture from Dr. Moss was tough; wait til you try a 15 hour flight! [Of course, that includes a 3 hour lay-over in NY]. JANUARY 07, 2006 First Day In Israel Hi from Nazareth! We made it to Israel safely and with almost all of our things. It is great to be here, but we are looking forward to a good night's rest. We left the airport around lunchtime today and spent the afternoon in Caesarea and Megiddo. We had our first taste of Israeli food at lunch in a local restaurant. It was a lot different from our typical American restaurants, but I think we all enjoyed it. Caesarea is a Roman city built on the Mediterranean by Herod a few years before Jesus was born. The city contains a theatre, bathhouse, aqueduct, and palace among other things. The theatre was large and had a beautiful view of the Mediterranean. There was an aqueduct (about 12 miles of which are still in tact) which provided water to the city. The palace, which sits on the edge of the water, was home to Pontius Pilot after Herod s death. We then went to Megiddo, which is a city, much of which was built by King Solomon over 3000 years ago. -

THE TEMPLE FAMILY ISRAEL TRIP 11 – 23, June 2019 (Draft March 2, 2018; Subject to Change)

THE TEMPLE FAMILY ISRAEL TRIP 11 – 23, June 2019 (Draft March 2, 2018; Subject to change) Exact day’s itinerary and timing for site visits will vary based on bus assignment Tuesday, 11 June – Depart Atlanta Wednesday, 12 June – Shehecheyanu! • Afternoon Group arrival in Israel to be met and assisted at Ben Gurion Airport by your ITC representative • Hotel check-in • Group “Meet and Greet” session at the hotel • Welcome dinner and Shehecheyanu at Dan Panorama Hotel Pool Area Overnight: Dan Panorama Hotel, Tel Aviv Thursday, 13 June – From Rebirth to Start Up Nation • Climb down into the amazing underground, pre-State bullet factory built by the Haganah under the noses of the British at the Ayalon Institute • Visit Independence Hall, relive Ben Gurion’s moving declaration of the State; discuss whether it seems that the vision of Israel’s founding fathers – articulated in the Scroll of Independence – has come to fruition, followed by lunch on your own and free time in Tel Aviv • Explore the new Sarona Gourmet Food Market with time to enjoy lunch at one of the specialty restaurants stalls or create your own picnic and enjoy the grounds • Visit the Taglit Center for Israel’s Innovation, with a guided interactive exhibition tour of the “Start-Up Nation” and see why Tel-Aviv was rated the 2nd most innovative ecosystem in the world after Silicon Valley. • Late afternoon free to enjoy at the beach or walking the streets of Tel Aviv • Dinner on own, with suggestions provided for the many exciting areas to explore in and around Tel Aviv and Jaffa Port Overnight: Dan Panorama Hotel, Tel Aviv 1 Friday, 14 June – Where It All Began • Enter the Old City of Jerusalem at a beautiful overlook and pronounce the shehecheyanu blessing with a short ceremony • Go way back in time to King David’s Jerusalem in David’s City • See the 3-D presentation and enjoy sloshing through Hezekiah’s water tunnel (strap-on water shoes and flashlights needed) • Lunch on one’s own in the Old City with a little time to shop in the Cardo • Enjoy your first visit to The Kotel, to visit and reflect. -

Jewish Heritage Duration: 10 Days / 9 Nights

Jewish Heritage Duration: 10 days / 9 nights A great value, best selling tour which takes in all the major Jewish highlights in Israel. Very reasonable rates and a choice of four hotel categories make this a very flexible option. Day Location Details Meal Highlights 1 TEL AVIV Your journey into your heritage begins when you arrive at Ben Gurion airport where you will be met by one of Professional Tour Director our representatives and transferred to your hotel. 6 Days of Sightseeing 9 night’s hotel accommodation 2 TEL AVIV Tel Aviv Spend the day settling into the warm Breakfast Entrance fees to the sites visited Mediterranean climate by exploring Tel Aviv at your as per program leisure and acquainting yourself with the city. All hotels taxes and service charges 3 CAESAREA • Today you will delve into some of Israel’s rich history by Breakfast HAIFA • ACRE visiting Caesarea, the Roman capital and the largest Dinner Meals • ROSH port in the Mediterranean. Visit the incredible Roman HANIKRA Theatre which has been completely restored, the Daily breakfast ( Israeli buffet ) aqueducts and the Crusader City. Head up to Mount Carmel for a spectacular view of Haifa and then visit Af Lunch at the Dead Sea (1 day ) Al Pi Chen, one of the famous ships that illegally Dinner at Kibbutz Lavi ( 2 nights ) brought Jews to Israel’s shores after WWII. Wander along the old harbor and through the local market in Tour Exclusions Acre before making your way to Israel’s northern tip, Rosh Hanikra. Descend down the 210 foot cliff by cable Transfer & assistance car to see the spectacular caverns and grottoes carved out by the pounding waves of the Mediterranean. -

Antiguo Oriente, N° 5

CUADERNOS DEL CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE HISTORIA DEL ANTIGUO ORIENTE ANTIGUO ORIENTE Volumen 5 2007 Facultad de Filosofía y Letras UCA Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires - Argentina CUADERNOS DEL CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE HISTORIA DEL ANTIGUO ORIENTE ANTIGUO ORIENTE Volumen 5 2007 Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires - Argentina Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Departamento de Historia Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Av. Alicia Moreau de Justo 1500 P. B. Edificio San Alberto Magno (C1107AFD) Buenos Aires Argentina Sitio Web: www.uca.edu.ar/cehao Dirección electrónica: [email protected] Teléfono: (54-11) 4349-0200 int. 1189 Fax: (54-11) 4338-0791 Antiguo Oriente se encuentra indizada en el Catálogo de LATINDEX y forma parte del Núcleo Básico de Publicaciones Periódicas Científicas y Tecnológicas Argentinas (CONICET) Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11.723 Impreso en la Argentina © 2007 UCA ISSN 1667-9202 AUTORIDADES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA ARGENTINA Rector Monseñor Dr. Alfredo Horacio Zecca Vicerrector Lic. Ernesto José Parselis AUTORIDADES DE LA FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS Decano Dr. Néstor Ángel Corona Secretario Académico Lic. Ezequiel Bramajo Director del Departamento de Historia Dr. Miguel Ángel De Marco CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE HISTORIA DEL ANTIGUO ORIENTE Directora Dra. Roxana Flammini Secretario Pbro. Lic. Santiago Rostom Maderna Investigadores Dra. Graciela Gestoso Singer Dr. Pablo Ubierna Lic. Juan Manuel Tebes Prof. Virginia Laporta Prof. Romina Della Casa Colaboradores María Busso Jorge Cano Francisco Céntola Eugenia Minolli CUADERNOS DEL CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE HISTORIA DEL ANTIGUO ORIENTE “ANTIGUO ORIENTE” Directora Dra. -

Theological Monthly

Concoll~i(] Theological Monthly DECEMBER • 1959 The Theology of Synagog Architecture (As Reflected in the Excavation ReportS) By MARTIN H. SCHARLEMANN ~I-iE origins of the synagog are lost in the obscurity of the past. There seem to be adequate reasons for believing that this ~ religious institution did not exist in pre-Exilic times. Whether, however, the synagog came into being during the dark years of the Babylonian Captivity, or whether it dates back only to the early centuries after the return of the Jews to Palestine, is a matter of uncertainty. The oldest dated evidence we have for the existence of a synagog was found in Egypt in 1902 and consists of a marble slab which records the dedication of such a building at Schedia, near Alexandria. The inscription reads as follows: In honor of King Ptolemy and Queen Berenice, his sister and wife, and their children, the Jews (dedicate) this synagogue.1 Apparently the Ptolemy referred to is the one known as the Third, who ruled from 247 to 221 B. C. If this is true, it is not unreasonable to assume that the synagog existed as a religious institution in Egypt by the middle of the third century B. C. Interestingly enough, the inscription calls the edifice a :JtQOOE'UXY!, which is the word used in Acts 16 for something less than a per manent structure outside the city of Philippi. This was the standard Hellenistic term for what in Hebrew was (and is) normally known as no.pi'1 n~, the house of assembly, although there are contexts where it is referred to as i1~!:l~i'1 n::1, the house of prayer, possibly echoing Is. -

May Sees the Final Results of the 27Th Annual Voluntary Campaign, and Our Hopes Are That We Have Another One Million-Dollar Fund-Raising Event

Spring Is Sprung Sir Knights, as you read this editorial, I hope that you can reflect on the happenings of the past months since the Grand Encampment Triennial Conclave in Denver last August. We are just recovering from a great fail and winter season. We are now in the first several weeks of spring, and looking forward to that part of the year that brings new hope for the future. We of the Grand Encampment have had a very busy fall and winter season with six most successful Department Conferences, Grand Commandery Conclaves, and many social obligations since our installation as your officers of the Grand Encampment in Denver. We have been in attendance at the 3rd International Conference of Grand Masters in Toronto, Canada; Sovereign Great Priory of Canada; Supreme Assembly of the Social Order of the Beauceant; my own reception from my Commandery here in St. Louis; Northern Jurisdiction of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite; Rose Bowl Parade; Grand Masters' Conference in Fargo; A.M.D. Week in Washington, DC; Knights Templar Eye Foundation meetings; Easter Sunrise Service in Washington, DC; and obligations too numerous to list. As those of you who have been in attendance at the Department Conferences know, all officers of the Grand Encampment have been present and share our agenda with you. We are looking forward to June when we will be in Chattanooga, Tennessee, for the Southeastern Department Conference, which will conclude our first year of this trienniums Department Conferences. May sees the final results of the 27th Annual Voluntary Campaign, and our hopes are that we have another one million-dollar fund-raising event. -

Coins from Tiberias

CHAPTER THREE T H E C O I N S Gabriela Bijovsky and Ariel Berman Of the 150 coins discovered during the excavations, from a thick layer of destruction related by the 85 belong to the metalwork hoard (see discussion excavators to the earthquake that struck Tiberias in below) and 65 are isolated coins retrieved during 749. Among the Umayyad material we include four the excavation.* Arab-Byzantine transitional coins (Nos. 28–31) Of the isolated coins (Pl. 3.1), almost half predate and two pre-reform anonymous ful¨s minted in the main occupation strata excavated at the site (of the Tiberias (Nos. 32–33). The group of post-reform Umayyad–Abbasid and Fatimid periods). Worthy of Umayyad ful¨s is quite diverse (Nos. 34–45). mention is an autonomous Seleucid coin from Tyre Worthy of mention is a fals minted at Hims and (No. 1). The rest (Nos. 2–27) constitute a wide and dated to 734/735 (No. 34). Eleven Abbasid coins continuous range of Roman–Byzantine bronze coins were discovered, most of them anonymous types from the first to sixth centuries CE. They include a made by casting (Nos. 46–56). coin of the procurator Ambibulus (No. 2), Roman The Carmathian and Fatimid coins are related Provincial issues minted in Caesarea (Nos. 3, 5) and to the latest and most relevant layer excavated in an antoninianus of Salonina (No. 6). The coins dated the site. The four Carmathian coins are silver or to the fourth–fifth centuries are conventional issues billon dirhams (Nos. 57–60). Coin No. -

Israel 2019 Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments are due to representatives of government ministries and agencies as well as many others from a variety of organizations, for their essential contributions to each chapter of this book. Many of these bodies are specifically cited within the relevant parts of this report. The inter-ministerial task force under the guidance of Ambassador Yacov Hadas-Handelsman, Israel’s Special Envoy for Sustainability and Climate Change of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Galit Cohen, Senior Deputy Director General for Planning, Policy and Strategy of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, provided invaluable input and support throughout the process. Special thanks are due to Tzruya Calvão Chebach of Mentes Visíveis, Beth-Eden Kite of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Amit Yagur-Kroll of the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Ayelet Rosen of the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Shoshana Gabbay for compiling and editing this report and to Ziv Rotshtein of the Ministry of Environmental Protection for editorial assistance. 3 FOREWORD The international community is at a crossroads of countries. Moreover, our experience in overcoming historical proportions. The world is experiencing resource scarcity is becoming more relevant to an extreme challenges, not only climate change, but ever-increasing circle of climate change affected many social and economic upheavals to which only areas of the world. Our cooperation with countries ambitious and concerted efforts by all countries worldwide is given broad expression in our VNR, can provide appropriate responses. The vision is much of it carried out by Israel’s International clear. -

Ancient Synagogues in the Holy Land - What Synagogues?

Reproduced from the Library of the Editor of www.theSamaritanUpdate.com Copyright 2008 We support Scholars and individuals that have an opinion or viewpoint relating to the Samaritan-Israelites. These views are not necessarily the views of the Samaritan-Israelites. We post the articles from Scholars and individuals for their significance in relation to Samaritan studies.) Ancient Synagogues in the Holy Land - What Synagogues? By David Landau 1. To believe archaeologists, the history of the Holy Land in the first few centuries of the Christian Era goes like this: After many year of staunch opposition to foreign influence the Jews finally adopted pagan symbols; they decorated their synagogues with naked Greek idols (Hammat Tiberias) or clothed ones (Beth Alpha), carved images of Zeus on their grave (Beth Shearim), depicted Hercules (Chorazin) and added a large swastika turning to the left (En Gedi) to their repertoire, etc. Incredible. I maintain that the so-called synagogues were actually Roman temples built during the reign of Maximin (the end of the 3rd century and beginning of the 4th) as a desperate means to fight what the roman considered the Christian menace. I base my conclusion on my study of the orientations of these buildings, their decorations and a testimony of the Christian historian Eusebius of Caesaria. 2. In 1928, foundations of an ancient synagogue were discovered near kibbutz Beth Alpha in the eastern Jezreel Valley at the foot of Mt. Gilboa. Eleazar Sukenik, the archaeologist who excavated the site wrote (1932: 11): Like most of the synagogues north of Jerusalem and west of the Jordan, the building is oriented in an approximately southerly direction. -

Did the Synagogue Replace the Temple?

Bible Review 12, no. 2 (1996). Did the Synagogue Replace the Temple? By Steven Fine In 70 C.E. Roman legions destroyed the Jerusalem Temple, Judaism’s holiest structure and the “dwelling place of God’s name.” Despite this loss, Judaism was to survive and prosper. In the following centuries, the synagogue itself came to be seen as a “holy place.” Does this mean, as some people suppose, that the synagogue as we know it developed after the destruction of the Temple and was, in fact, its replacement? Not exactly. Communal meeting places that we can recognize as synagogues existed while the Temple still stood, at least by the midfirst century B.C.E. The second part of the question—Did the synagogue replace the Temple?—is not so easily answered. The origins of the synagogue are shrouded in mystery, and scholarly opinions as to its beginnings vary. Some scholars trace its development to the First Temple period, others to the Exile in Babylonia, and still others (including the author) to the latter Second Temple period in Palestine. Virtually all scholars recognize that the synagogue was a welldeveloped institution at least a century before the Romans destroyed the Temple. Synagogues in the Land of Israel are mentioned by the Jewish philosopher, exegete and communal leader Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 B.C.E.40 C.E.); by the firstcentury C.E. Jewish historian Flavius Josephus; in the New Testament; and in rabbinic literature. Archaeology provides additional evidence for the early dating of the origins of the synagogue.