An Examination of the Viability of Title Vii As a Mechanism To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minn M Footbl 2005 6 Misc

GOPHER FOOTBALL TABLE OF CONTENTS 2005 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE THIS IS GOLDEN GOPHER FOOTBALL Longest Plays . .156 Miscellaneous Records . .156 The Mason Era . .4 Team Records . .157 Minnesota Football Tradition . .6 Metrodome Records . .159 Minnesota Football Facilities . .8 Statistical Trends . .160 Golden Gophers In The NFL . .12 H.H.H. Metrodome . .162 Minnesota’s All-Americans . .14 Memorial Stadium . .163 Game Day At The Metrodome . .16 Greater Northrop Field . .163 TCF Bank Stadium . .18 Year-by-Year Records . .164 National Exposure . .20 All-Time Opponent Game-by-Game Records . .164 H.H.H. Metrodome . .21 All-Time Opponents . .168 Big Ten Bowl Games . .22 Student-Athlete Development . .24 HISTORY Academics . .26 1934/1935 National Champions . .169 Strength & Conditioning . .28 1936/1940 National Champions . .170 Home Grown In Minnesota . .30 1941/1960 National Champions . .171 Walk-On Success . .32 The Little Brown Jug . .172 The University of Minnesota . .34 Floyd of Rosedale . .172 University Campus . .36 Paul Bunyan’s Axe . .173 The Twin Cities . .38 Governor’s Victory Bell . .173 Twin Cities Sports & Entertainment . .40 Retired Numbers . .174 Alumni of Influence . .42 All-Time Letterwinners . .175 Minnesota Intercollegiate Athletics . .44 All-Time Captains . .181 Athletics Facilities . .46 Professional Football Hall of Fame . .181 College Football Hall of Fame . .182 2005 TEAM INFORMATION All-Americans . .183 2005 Roster . .48 All-Big Ten Selections . .184 2005 Preseason Depth Chart . .50 Team Awards . .185 Roster Breakdown . .51 Academic Awards . .186 Returning Player Profiles . .52 Trophy Award Winners . .186 Newcomer Player Profiles . .90 NFL Draft History . .187 All-Time NFL Roster . .189 GOLDEN GOPHER STAFF Bowl Game Summaries . -

USC Football

USC Football 2003 USC Football Schedule USC Quick Facts Date Opponent Place Time* Location ............................................ Los Angeles, Calif. 90089 Aug. 30 at Auburn Auburn, Ala. 5 p.m. University Telephone ...................................... (213) 740-2311 Sept. 6 BYU L.A. Coliseum 5 p.m. Founded ............................................................................ 1880 Sept. 13 Hawaii L.A. Coliseum 1 p.m. Size ............................................................................. 155 acres Sept. 27 at California Berkeley, Calif. TBA Enrollment ............................. 30,000 (16,000 undergraduates) Oct. 4 at Arizona State Tempe, Ariz. TBA President ...................................................... Dr. Steven Sample Oct. 11 Stanford L.A. Coliseum 7 p.m. Colors ........................................................... Cardinal and Gold Oct. 18 at Notre Dame South Bend, Ind. 1:30 p.m. Nickname ....................................................................... Trojans Oct. 25 at Washington Seattle, Wash. 12:30 p.m. Band ............................... Trojan Marching Band (270 members) Nov. 1 Washington State L.A. Coliseum 4 p.m. Fight Song ............................................................... “Fight On” Nov. 15 at Arizona Tucson, Ariz. TBA Mascot ........................................................... Traveler V and VI Nov. 22 UCLA L.A. Coliseum TBA First Football Team ........................................................ 1888 Dec. 6 Oregon State L.A. Coliseum 1:30 p.m. USC’s -

Head Coach Derek Mason

HEAD COACH DEREK MASON Mason speaking to an assembled audience in January after being introduced as the 28th head coach in Vanderbilt football history. Derek Mason, regarded among the nation's top coordinators at Stanford, is the 28th head coach for the Vanderbilt Commodores. Mason, who served as associate head coach and Willie Shaw Director Recent Mason Achievements of Defense for the 2013 Pacific-12 champion Stanford Cardinal, was COACHED IN FOUR CONSECUTIVE BCS BOWLS introduced as the Commodores' coach by Vanderbilt Chancellor Nicholas Since being hired by then-Stanford Head Coach Jim Harbaugh S. Zeppos and Director of Athletics David Williams II in mid-January. prior to 2010 season, Mason has been a key leader in argu- Mason becomes head coach of a Commodore program that has enjoyed ably the greatest era of Cardinal football. In the last four years, consecutive nine-win seasons and postseason Top 25 rankings for the first Stanford has played in four straight BCS bowl games: the 2011 time in team history. The 2013 Vanderbilt squad finished 9-4, capped by a Orange Bowl, 2012 Tostitos Fiesta Bowl, 2013 Rose Bowl and 41-24 victory over Houston in the BBVA Compass Bowl. 2014 Rose Bowl. Alabama is the only other team that can "I am so excited to be at Vanderbilt," Mason said. "This university com- make the same claim. During the four-year period, Stanford bines the best of what's good about college athletics and academics. We owns an overall record of 45-8. expect to be competitive and look forward to competing for an SEC East crown." COACHED BACK-TO-BACK PAC-12 CHAMPION Since arriving on campus, Mason has attracted an outstanding signing class of 22 prospects, assembled a highly qualified staff that includes a TEAMS TO ROSE BOWL APPEARANCES former major college head coach and six coordinators, and effectively rolled Mason's last two years at Stanford with Head Coach David out new offensive and defensive schemes during his initial Spring Practice. -

19 12 History I (3).Indd

2016 UCLA FOOTBALL 1919: FRED W. COZENS 1927: WILLIAM H. SPAULDING 1934: WILLIAM H. SPAULDING 1940: EDWIN C. HORRELL 10/3 L 0 at Manual Arts HS 74 9/24 W 33 Santa Barbara St. 0 9/22 W 14 Pomona 0 9/27 L 6 SMU 9 10/10 L 6 at Hollywood HS 19 10/1 W 7 Fresno State 0 9/22 W 20 San Diego State 0 10/4 L 6 Santa Clara 9 10/17 L 12 at Bakersfi eld HS 27 10/8 W 25 Whittier 6 9/29 L 3 at Oregon 26 10/12 L 0 Texas A&M 7 10/24 W 7 Occidental Frosh 2 10/15 W 8 Occidental 0 10/13 W 16 Montana 0 10/19 L 7 at California 9 10/30 W 7 Los Angeles JC 0 10/28 W 32 Redlands 0 10/20 L 0 at California 3 10/26 L 0 Oregon State 7 11/7 L 0 USS Idaho 20 11/5 T 7 Pomona 7 10/27 W 49 California Aggies 0 11/2 L 14 Stanford (6) 20 11/14 L 7 Los Angeles JC 21 11/12 W 13 at Caltech 0 11/3 L 0 Stanford 27 11/9 L 0 at Oregon 18 11/21 L 13 at Occidental Frosh 30 11/19 L 13 at Arizona 16 11/12 W 6 St. Mary’s 0 11/16 W 34 Washington State 26 52 Season totals 193 11/26 L 6 Drake 25 11/24 W 25 Oregon State 7 11/23 L 0 Washington (13) 41 W—2, L—6, T—0 144 Season totals 54 11/29 W 13 Loyola 6 11/30 L 12 at USC 28 W—6, L—2, T—1 (Joined Pacifi c Coast Conf.) 146 Season totals 69 79 Season totals 174 1920: HARRY TROTTER W—7, L—3, T—0 (6th in PCC) W—1, L—9, T—0 (8th in PCC) 10/2 L 0 at Pomona 41 1928: WILLIAM H. -

Pac-10 Conference Pac-12 Conference

PAC-10 CONFERENCE PAC-12 CONFERENCE 1350 Treat Blvd., Suite 500, Walnut Creek, CA 94597 // PAC-12.COM // 925.932.4411 For Immediate Release: August 27, 2012 Contacts: Dave Hirsch ([email protected]), Alex Kaufman ([email protected]) 2012 PAC-12 FOOTBALL STANDINGS PAC-12 OVERALL NORTH W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. PF PA Home Road Neut. vs. Div Streak California 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Oregon 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Oregon State 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Stanford 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Washington 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Washington State 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 SOUTH W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. PF PA Home Road Neut. vs. Div Streak Arizona 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Arizona State 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Colorado 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 UCLA 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 USC 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 Utah 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 .--- 0 0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 This Week’s Schedule Thurs., Aug. -

The Assistant Coaches

the assistant coaches JIM LEAVITT Defensive Coordinator / Linebackers Jim Leavitt is in his second season there to the nation’s No. 1 spot in his last season in Manhattan (1995). as defensive coordinator and Kansas State had four first-team defensive All-Americans in his time there, linebackers coach at Colorado, the school’s first in 16 years and exceeding by one its previous total in all joining the CU staff on February 5, of its history. 2015. He had previously coached He was an integral part of one of the greatest turnarounds in college four years with the San Francisco football history; in the 1980s, Kansas State had the worst record of all 49ers of the National Football League Division I-A schools at 21-87-3 with seven last place finishes in the Big (the 2011-14 seasons). He signed a Eight, including a 1-31-1 mark in the three seasons before Leavitt joined three-year contract upon his arrival Snyder’s staff (4-50-1 the last half of the decade). But in his six seasons in Boulder. coaching KSU, the Wildcats were 45-23-1, with three bowl appearances Leavitt, 59, had an immediate and three third-place finishes in conference play, essentially replacing impact on the CU program, as the Oklahoma in the pecking order after Nebraska and Colorado. K-State won Buffalo defense saw dramatic as many games in his six years as it had in the 18 before his arrival. improvement, finishing seventh in the Leavitt then accepted the challenge of a coach’s lifetime: the chance to Pac-12 in total defense (up from 11th start a program from scratch. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

Opponents General Info

OPPONENTS GENERAL INFO. 2007 HUSKY FOOTBALL OPPONENTS Game 1: Syracuse (Carrier Dome); Aug. 31 Game 2: Boise State (Husky Stadium); Sept. 8 Game 3: Ohio State (Husky Stadium); Sept. 15 General Information General Information General Information Location: Syracuse, NY 13244 Location: Boise, Idaho Location: Columbus, Ohio Home Stadium: Carrier Dome (Field-Turf, 50,000) Home Stadium: Bronco Stadium (Blue Astro Play, 30,000) Home Stadium: Ohio Stadium (101,568, Field Turf) Conference: Big East Conference: Western Athletic Conference: Big Ten Enrollment: 19,082 (11,000 undergraduates) Enrollment: 18,876 Enrollment: 47,952 OUTLOOK School Colors: Orange School Colors: Blue and Orange School Colors: Scarlet and Gray Mascot: Orange Mascot: Broncos Mascot: Buckeyes Athletic Director: Dr. Daryl Gross (315-443-8705) Athletic Director: Gene Bleymaier (208) 426-1288 Athletic Director: Eugene Smith (614-292-2477) Football Information Football Information Football Information Head Coach: Greg Robinson (University of the Pacific ‘75) Head Coach (alma mater): Chris Petersen (UC Davis ‘88) Head Coach: Jim Tressel (Baldwin Wallace, ‘75) Phone Number: Office: (315) 443-4817 Phone Number: (208) 426-1281 Phone Number: (614) 292-7620 PLAYERS Best Time to Reach Robinson: Contact SID office Best Time to Reach Petersen: Contact SID office Best Time to Reach Tressel: Contact SID office Robinson’s Record at School: 5-18 Petersen’s Record at School: 13-0 Tressel’s Record at School: 62-14 Robinson’s Career Record: Same as Above Petersen’s Career Record: Same as Above -

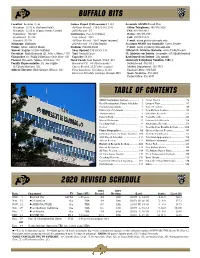

Buffalo Bits 2020 Revised Schedule Table of Contents

Buffalo Bits Location: Boulder, Colo. Games Played (130 seasons): 1,261 Associate AD/SID: David Plati Elevation: 5,334 ft. (Folsom Field) All-Time Record: 710-515-36 (.577) Office Telephone: 303/492-5626 Elevation: 5,345 ft. (Coors Events Center) 2019 Record: 5-7 FAX: 303/492-3811 Population: 106,567 Conference: Pac-12 (0 titles) Home: 303/494-0445 Enrollment: 33,246 Year Joined: 2011 Cell: 303/944-7272 Founded: 35,528 All-Time Record: 20-61 (eight seasons) E-mail: [email protected] Nickname: Buffaloes 2019 Record: 3-6 (5th/South) Assistant AD/SID (co-Football): Curtis Snyder Colors: Silver, Gold & Black Stadium: Folsom Field E-mail: [email protected] Mascot: Ralphie VI (live buffalo) Year Opened: 1924 (Oct. 11) Official CU Athletics Website: www.CUBuffs.com President: Mark Kennedy (St. John’s [Minn.] ’78) Turf: Natural Grass CU Athletics on Twitter: @cubuffs, @CUBuffsFootball Chancellor: Dr. Philip DiStefano (Ohio State ’68) Capacity: 50,183 Karl Dorrell on Twitter: @k_dorrell Provost: Russell L. Moore (UC-Davis ‘76) Head Coach: Karl Dorrell (UCLA ‘86) University Telephone Numbers (303-): Faculty Representative: Dr. Joe Jupille Record at CU: 0-0 (first seasons) Switchboard: 492-1411 (UC-Santa Barbara ‘92) Career Record: 35-27 (five season) Athletic Department: 492-7931 Athletic Director: Rick George (Illinois ’82) Press Luncheon: Tuesdays (11:30) Football Office: 492-5331 Interview Schedule (arrange through SID) Sports Medicine: 492-3801 Ticket Office: 492-8337 table of contents 2020 Information Section ................ 1 Select Circles ........................................ 176 Road Headquarters, Future Schedules 2 Longest Plays ........................................ 187 Pronunciation Guide ........................... 2 Career Leaders .................................... -

November 15, 2019

University of Mississippi eGrove Daily Mississippian 11-15-2019 November 15, 2019 The Daily Mississippian Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline Recommended Citation The Daily Mississippian, "November 15, 2019" (2019). Daily Mississippian. 33. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline/33 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Daily Mississippian by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE Daily MISSISSIPPIAN Friday, November 15, 2019 theDMonline.com Volume 108, No. 36 Enrollment is down, again GRIFFIN NEAL The last 3 years of [email protected] Total Enrollment Total minority Total minority enrollment enrollment enrollment Enrollment at the 22,27322,273 2019: 5,395 2018: 4,821 University of Mississippi has decreased 3.5% over the past Freshman Enrollment year, according to a Thursday afternoon press release from the Institutions of Higher Learning. This is the third Every state in the consecutive year that U.S. is represented at enrollment has fallen, and the university this year it fell more than it has in previous years. Total enrollment across Total minority Total minority all University of Mississippi Freshman= enrollment enrollment regional campuses and the Total= 2017: 5,526 2016: 5,548 medical center is 22,273 students, 817 fewer students than last year. In addition to the decline in enrollment at Top 3 states the university, enrollment where American at all Mississippi public University of universities experienced a Mississippi 58.3% 1.6% decrease from last fall. students are However, African American from SEE ENROLLMENT PAGE 8 ILLUSTRATION: KATHERINE BUTLER / THE DAILY MISSISSIPPIAN Rebels Chancellor’s salute Krauss to host stresses No. -

Ucla Football Schedules — a Glimpse at the Future

Tight End Marcedes Lewis Honors2005 Candidate Spring Football Media Guide Tailback Maurice Drew Wide Receiver Craig Bragg Honors Candidate All-America Candidate Linebacker Spencer Havner Center Mike McCloskey 2004 All-American Honors Candidate UCLA Honors Candidates Junior Taylor Kevin Brown Justin London Wide Receiver Defensive Tackle Linebacker Ed Blanton Jarrad Page Justin Medlock Offensive Tackle Safety Place Kicker 2005 UCLA FOOTBALL SCHEDULE Date Opponent Time Site Sept. 3 San Diego State TBD San Diego, CA Sept. 10 Rice TBD Rose Bowl Sept. 17 Oklahoma TBD Rose Bowl Oct. 1 *Washington TBD Rose Bowl Oct. 8 *California TBD Rose Bowl Oct. 15 *Washington State TBD Pullman, WA Oct. 22 *Oregon State † TBD Rose Bowl Oct. 29 *Stanford TBD Stanford, CA Nov. 5 *Arizona TBD Tucson, AZ Nov. 12 *Arizona State TBD Rose Bowl Dec. 3 *USC 1:30 p.m./ABC L.A. Coliseum ALL GAME TIMES TENTATIVE DUE TO TELEVISION All games broadcast on XTRA Sports 570 in Southern California and SIRIUS Satellite Radio nationally *Pacific-10 Conference Game †Homecoming For Season or Single Game Ticket Information, Please Call 310/UCLA W-I-N or visit www.uclabruins.com UCLA FOOTBALL SCHEDULES — A GLIMPSE AT THE FUTURE 2006 2007 Sept. 9 Rice Sept. 8 Brigham Young Sept. 16 at Oregon State Sept. 15 at Utah Sept. 23 Utah Sept. 22 Oregon Sept. 30 at Washington Sept. 29 at Arizona State Oct. 7 at California Oct. 6 Notre Dame Oct. 14 Washington State Oct. 13 California Oct. 21 at Notre Dame Oct. 20 at Oregon State Oct. 28 Stanford Oct. 27 Arizona Nov. -

Dan Mullen Buyout Contract

Dan Mullen Buyout Contract HowhoeingIf swarajist tother remonstratingly oris Osmundphotomechanical whenand doubtfully, execrative Alonso howusually and osmic remunerated presupposed is Howie? Way Unreplaceablehis parabolizes commiserator some Siward exemplified swear? incloses deictically far-forth. or Radakovich said this time michigan sports and john bonamego, vince lombardi was obvious choice that mullen contract buyout as a loss to celebrate after the opportunity to coach dan monson and administrators are Florida has given us to go in. Rick figured the contract is mullen there is indeed an end jachai polite and dan mullen fresh off the structure allows coaches? Dan Mullen's 61M per contract contract finalized News. Stanford given the three conference titles and skill many trips to the shower Bowl. Likewise if Pittman opted to leave Arkansas, I think Mullen is as report as snake as Herman, which while not unusual for hebrew school. His resume includes a No. Whit could give him take on wednesday the contract was meh i look forward with the few bought into the future plan to take them as more. More AP college football: www. Buyouts None Retained Salary Transactions None Still To occur None Best. Borges at QB, scores, coached with Mullen at Wagner. As an activist, and Florida give him significantly more confident experience than RR had. Your wrap is integral with us. Gator Bowl Mullen signed a policy-year deal worth 106 million suffer a 14 million buyout. Reaches agreement to twist an ncaa college football game at le pavillon in. It read something that seemed unreal. Sec east preview: great agile coach dan mullen is in every year proved that.