Salyan. Some Plants Have Already Started to Yield Fruit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TSLC PMT Result

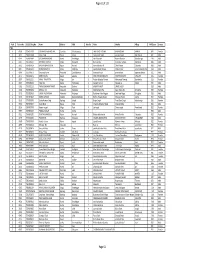

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

Annex-9 Details of Stations/Sites to Be Connected by Broadband Network 9.1

Annex-9 Details of stations/sites to be connected by broadband network 9.1. Introduction The RFA for building and operate broadband connectivity in 3 Districts of Province No. 2 of Nepal. There are in total 3 Districts among which 4 districts are included in Each Package A, Packages are distributed as an inaccessible, Seasionally accessible and Accessible all time by vehicle are covered under this RFA as shown in Table 9.1a-b. NCB: IFA No. 04/NTA/2074/075 to build Broad Band network and provide internet access connectivity services in 3 districts of Province 6. 95 In most of these districts, 2G and 3G celular mobile tchnologies, optical Fiber, VSAT, wireless, Radio Relay Links have been laid by different service providers. They might be in a position to lease the bandwidth for other Internet service providers of the country. In such situation, the Applicant may propose the leasing of existing network and extend it to the required locations either by using suitable technologies. The summary of the broadband internet connectivity points/stations/sites are presented in the Table 9.1a and details of each package are presented in the Table 9.1b. Applicants are requested to prepare a site/station/location wise Bill of Quantity/Bill of Materials based on Table 9.1b NCB: IFA No. 04/NTA/2074/075 to build Broad Band network and provide internet access connectivity services in 3 districts of Province 6. 96 Table 9.1a Summary of the Broadband Internet Access points: 1. S.N. Name of (RURAL) MUNICIPALITY No of School No of Grand Total District Health Centre No of (Rural) No of No of Secondary/ Higher Total Munciplity Munciplity Wada Secondary School Number of Site 1 Surkhet 4 5 99 76 72 694 2 Dailekh 7 4 90 80 69 3 Salyan 7 3 83 46 49 Grand Total 18 12 272 202 190 Surkhet, Dailekh and Salyan Note: 1. -

Government of Nepal National Vigilance Centre Singhdurbar, Kathmandu

Government of Nepal National Vigilance Centre Singhdurbar, Kathmandu Name of Routine Maintenance(RM) Roads of SNRTP Projects for Technical Audit on Fiscal Year 2073/074 Actual length S. Contract Package District S.N. Project Name Length for TA No. (Km) (km) 1 Kabhigoth-Bariyarpur 25.00 10.00 2 Halkhoriyai-MRM-Katghat 7.71 7.71 3 Kalaiya_Gangvawanipur_Malahi 18.30 10.00 4 Kalaiya-Jaitapur Road (Mukhalal Marga) 11.53 10.00 NVC/TA/SNRTP/ Bhaluhi - Inarwasira - Rajghatta - Mahendra 1 BARA 5 RM-073/074- 01 Highway 12.00 10.00 6 Kolbi-Maduwan 11.50 10.00 7 Khekhariya-Pheta-Motisar-Kalaiya 6.14 6.14 8 Piparpati-Bairiya-Kotwali 8.80 8.80 TOTAL LENGTH(KM) 100.98 72.65 1 Bhojpur-Dingla-Mulpani-Keurenipani 39.60 10.00 Dingla-Mulpani-Khartamchha-Kudak-Kaule- 10.19 10.19 2 Dobhane-Road 3 Dingla-Baluwabesi-Kulung 10.50 10.50 NVC/TA/SNRTP/ 4 Taksargumba-Dalgau-Bhulke-Okhre 30.82 10.00 2 BHOJPUR RM-073/074- 02 5 Khairang Patale Pani Hasanpur Road 8.78 8.78 6 Ghoretar Ranibas Manebhanjyang Road 47.30 10.00 Tiwari Bhanjyang Chyangre Bastim Thulo Duma 27.36 10.00 7 Sano Duma Road TOTAL LENGTH(KM) 174.55 69.47 1 Siktar-Budhathum-Baseri-Manbu-Lapa-Road 16.00 10.00 Siktar-aginchowk-salyankot-sukhbhangyang- 17.60 10.00 2 phulkharka-ri-road Hepinge-Khahara-Rigne-Satdobato-Chimchok-Ri 16.00 10.00 3 Road Palpabhanjyang-Hulakbhanjyang-Chainpur- 20.66 10.00 4 Rampur-Bangeraha Hulakbhanjyang-Sadhbhanjyang-Khari- 16.00 10.00 NVC/TA/SNRTP/ 5 3 DHADING-1 Bhunkotghat-Rampur Road RM-073/074- 03 Sadhbhangyang-Dhola-Dudebhangyang- 14.50 10.00 6 Samibhangyang-Satdobato-Thulichaur- -

![Xf]D Axfb'/ &Fs"/ Cfs[Lt Kgyl ऋृषिराम प](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1276/xf-d-axfb-fs-cfs-lt-kgyl-7451276.webp)

Xf]D Axfb'/ &Fs"/ Cfs[Lt Kgyl ऋृषिराम प

खुला प्रलतयोलगता配मक परीक्षाको वीकृ त नामावली वबज्ञापन नं. : २०७७/७८/३३ (लुम्륍बनी प्रदेश) तह : ३ पदः कलनष्ठ सहायक (गो쥍ड टेटर) रोल नं. उ륍मेदवारको नाम उ륍मेदवारको नाम ललंग सम्륍मललत हुन चाहेको समूह थायी म्ि쥍ला थायी न. पा. / गा.वव.स बािेको नाम बाबुको नाम 1 AACHAL SINGH THAKUR आँचल l;+x &fs"/ Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Banke Sub- Metropolitan Nepalgunj eujtL l;+x &fs"/ xf]d axfb'/ &fs"/ 2 AAKRITI PANTHI cfs[lt kGyL Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Gulmi Thanapati ऋृषिराम पन्थी बाबुराम पन्थी 3 AAKRITI GIRI cfs[tL lu/L Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Rolpa Sunil Smiriti vu" lu/L zf]ef/fd lu/L 4 AARATI KHANAL cf/lt vgfn Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Tehrathum Solma lglwgfy vgfn led k|;fb vgfn 5 AARTI PARIYAR आरती पररयार Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Banke Nepalgunj भोटे ष िंह पररयार षबष्ण ु पररयार 6 AASHA BASEL cfiff a;]n Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Pyuthan Belbas VDC l/vL/fd h};L k"gf/fd h};L 7 AASHA GHIMIRE cfzf l#ld/] Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Arghakhanchi patauti lxdnfn l#ld/] sdn k|;fb l#ld/] 8 AASTHA SHRESTHA cf:yf >]i& Female ख쥍ु ला, महिला Rupandehi Butwal dVvg nfn >]i& lji)f" nfn >]i& 9 AAWSAHAYAK MANI PANDEY अवशायक मषण पाण्डoे Male ख쥍ु ला Rupandehi Rohini षशतल प्र ाद पाण्डे षदनकर मषण पाण्डे 10 AAYUSHMA HAMAL K.C. -

Page 1 of 66

PMT Result Sheet 2077/078 Token Ward PMT Rank SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika Father Mother Village Quintile Gender No No Score 1 50143 6770010003 ASHOK JOSHI Bajhang Lamatola 8 Ammar raj joshi Gyandevi joshi Ranigau 910 1 Male 2 49402 767700300007 bharat kami Bajhang Deulekh 4 birjit kami mallabhatada 916.4 1 Male 3 49539 7566088041 MAN KUMARI NEPALI Surkhet Hariharpur 5 INDRA BIR DAMAI DIL KUMARI DAMAI DOPKA 917.9 1 Female 4 50519 7361016007 JANAKI KATHAYAT Dolpa Tripurakot 1 HIRA BAHADUR KATHAYAT RAM KUMARI KATHAYAT KATHAYAT TOL 918.9 1 Female 5 49590 6870006043 NARESH SARKI Bajhang JAYA SARKI LACHHU SARKI 919.4 1 Male 6 45068 763320310031 DEV LOHAR Bajura Jugada 3 SARPA LAL KAMI PAMPHA KAMI JUGADA 919.8 1 Male 7 50520 7369002013 Basanti Budha Bajura Kolti 3 Sharke budha Budi bista Cholu 920.2 1 Female 8 49644 766660400074 SANGITA SUNAR Surkhet Taranga 4 LAL BAHADUR SUNAR KHAGI SARA SUNAR SAJGHAT 920.4 1 Female 9 48644 767750700024 MANJU BOHARA Baitadi Mathairaj 7 GAJ BAHADUR BOHARA KUTURI BOHARA DWARI 921 1 Female 10 50075 766590040009 ASMITA MAHATARA Humla ShreeNagar 1 Prem mahatara Pankali Mahatara Kalkhe 922 1 Female 11 50082 766590040012 BACHA MAHATARA Humla ShreeNagar 1 Dabale mahatara Chimsi mahatara Kalkhe 922 1 Male 12 47042 767740230003 DAMANTI TAMATA Darchula Eyarkot 2 BAHADUR RAM TAMATA NANTA DEVI TAMATA SUNNAMUNNA 922 1 Female 13 46458 767740240025 KUMARI RAMITA THAGUNNA Darchula Earkot 1 HAR SINGH THAGUNNA BHANA DEVI THAGUNNA EARKOT 922 1 Female 14 47032 7274047032 RAJENDRA SINGH THEKARE Darchula Eyarkot 2 AMMAR SINGH -

Final Report for Rti, Health for Life

RTI, HEALTH FOR LIFE FINAL REPORT FOR This document compiles introduction of the project, information on the program implementation, program design, main achievements made and constraint faced during the implementation period and lessons learnt. [ A n t e n n a F o u n d a t i o n Ne p a l ] [ K u s u n t i M a r g , E k a n t a k u n a , L a k i t p u r ] [ 5 0 0 0 0 8 4 , 5 0 0 0 0 8 0 ] [5 5 4 5 8 5 7 ] [ 3 F e b r u a r y 2 0 1 5 ] FINAL REPORT FOR RTI, HEALTH FOR LIFE SUB-CONTRACT INFORMATION Subcontract Number 5-330-0213728-field under USAID Contract Number AID-367-C-13- 00001 entitled “Communication program initiative under the funding support of Health for Life” Name of Sub-Contractor: Antenna Foundation Nepal Date of Submission: 4 February 2015 Date Page 1 FINAL REPORT FOR RTI, HEALTH FOR LIFE LIST OF ABBREVIATION AFN Antenna Foundation Nepal AHW Auxiliary Health Worker ANM Auxiliary Nurse Midwife CAG Content Advisory Group DPHO District Public Health Office DHO District Health Office FCHVs Female Community Health Volunteers FM Frequency Modulation H4L Health for Life HIV/AIDS and STD Human Immunodeficiency Virus/ Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Sexually Transmitted Disease HFOMC Health Facility Operation and Management Committee JKLS Jeewan Ka Lagi Swasthya Date Page 2 FINAL REPORT FOR RTI, HEALTH FOR LIFE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The main achievements made during the implementation period are - x Enhanced capacity of radio program producers in areas of quality radio content by including field reports, investigative reporting, stories of success and failures; production of radio PSAs; skills for conducting public hearing x Promoted health as a “main news” by radio stations like Radio Buddha Awaaj, Kapilvastu FM, Dhurbatara FM, Deurali FM, Radio Bheri, Bulbule FM, Nepali Awaaj, Radio Krishnasar, Radio Tulsipur, Naya Yug FM, Sworgadwari FM, Radio Kapurkot, Radio Rapti, Radio Sisne, Radio Rolpa and Radio Mandavi. -

Annual Report and District Wise Successful Stories, Plans, Strategies and Publications

Backward Society Education (BASE) Annual Progress Report 2006 Central Project Office Tulsipur-6, Rajaura Dang Phone: +977-82-520055, 522212 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nepalbase.org 1 Table of Content Page 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................. 03 Vision, Mission, Goal, Goal............................................................................. 03 Objective:........................................................................................................ 04 2. SUMMARY...................................................................................................... 05 3. THE MAIN ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE CURRENT FISCAL YEAR.............. 06 PROGRAMS.................................................................................................................11 4. EDUCATION PROGRAM................................................................................ 11. 4.1 Education and Child Development.........................................................11. 4.2 Campaign for the Protection of Children Affected by Conflict............. ..31. 4.3 Sponsorship Management Program.......................................................31 4.4 Income Generating Program................................................................. 31. 4.5 Health Program.................................................................................... 34. 4.6 Disaster Preparedness and Response.................................................. 36 4.7 Organizational Development -

In UML Split, Maoist Centre Sees Chance at Regaining Its Relevance

WI THOUT F EAR O R F A V O U R Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXIX No. 186 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 35.4 C 14.0 C Monday, August 23, 2021 | 07-05-2078 Janakpur Jomsom In UML split, Maoist Centre sees chance at regaining its relevance As Madhav Nepal moves to register new party, the former rebel party, under threat of being wiped out of political scene, appears to be major beneficiary besides Congress. TIKA R PRADHAN Observers say while the Nepali KATHMANDU, AUG 22 Congress is likely to make a comeback after its massive loss in the 2017 elec- Once registered with the Election tions as the first party due to the UML Commission, Madhav Nepal’s CPN split, the Maoist Centre can make an (Unified Socialist) party is most likely attempt to prove its relevance. to extend support to the Sher Bahadur “A split in the UML was Dahal’s Deuba government, in return for some interest, rather than Deuba’s. That’s ministerial berths. Nepal has already why Maoist chair Dahal was making a applied for registration after splitting push for it,” said Lok Raj Baral, a pro- from the CPN-UML, which he led for fessor of political science. 15 years from 1993 to 2008. Nepal’s “There is a realisation in the Maoist decision to part ways with KP Sharma Centre that its relevance is over and it Oli, the UML chair, makes Deuba, or does not have any agenda to sell dur- the Nepali Congress for that matter, ing the elections.” the beneficiary. -

PMT Result-2019-2076-06-07.Xlsx

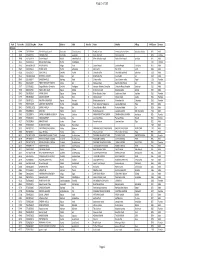

Page 1 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender Diploma 1 40944 7335076004 Dinesh Prasad patel Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 Ramakant raut devratiya kumari devi pipariya dostiya 895.3 Male 2 38430 7074002055 SAPANA PANT Darchula Sankarpur 8 Prem Raj Pant Dura Devi Pant 895.5 Female 3 39088 7573255014 Dream Nepali Kailali RamsikharJhala 5 Bhim bahadur nepali Parbati devi nepali janakpur 897.7 Male 4 36314 6559094024 Bhupendra Rokaya Humla ShreeNagar 5 905 Female 5 39914 666060007039 MANA NEPALI Mugu Photu 3 Gyane Nepali Jaukala Nepali Tali Libru 907.5 Male 6 36391 7259016011 HANSA KARKI Humla Sarkeedeu 9 Suka Karki Kari Karki sarke 908.6 Male 7 42326 7519101027 SAJAL KAFLE Sindhuli Phokari 8 Lilanath Kafle Tika kafle (pokhrel) phokhari 910 Male 8 36213 756000115029 NAMARAJ BUDHA Mugu Seri 9 Bhakta Budha Puni Budha seri 912.6 Male 9 35645 6229038047 ISHWORI MALLA Bajhang Rayal 1 Chitra malla Sanu Kumari malla Rayal 913 Female 10 35992 7160012064 PREM PRAKASH TAMATA Mugu Seri 2 Manasur Kami BanchuKala Tamata seri 914.6 Male 11 39377 6919050010 Durga Bahadur Shrestha Sindhuli Kholagaun 8 Narayan Bahadur Shrestha Chandra Maya Shrestha Ginchaur 915.1 Male 12 44500 9860612960 Pabitra Bdr shahi Bajura Gotree 4 birkha Bdr shahi patakala saha gotree 915.7 Male 13 38631 7569002063 JANAKI SHAHI Bajura Gotree 1 Bhim Bahadur Shahi Saileshwori Shahi baskena 916.7 Female 14 37770 7063002010 SANGITA KHATRI Jumla Birat 8 Motilal khatri Shanti khatri Ludku 918.1 Female 15 36849 7269004111 RANJITA KUMARI