Amnesty International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tainted Peace: Torture in Sri Lanka Since May 2009

Tainted Peace: Torture in Sri Lanka since May 2009 in Sri Lanka Torture Peace: Tainted Tainted Peace: Torture in Sri Lanka since May 2009 Freedom from Torture August 2015 Torture Freedom from Freedom from Torture 111 Isledon Road London N7 7JW Registered charity no: England 1000340, Scotland SC039632 Freedom from Torture August 2015 Front cover photo: A Sri Lankan soldier stands in front of a war monument in Kilinochchi, Sri Lanka. Back cover photo: A Tamil, who is a survivor of torture at the hands of Sri Lankan security forces, displays significant burns on his back. Photos: Will Baxter http://willbaxter.photoshelter.com Freedom from Torture Freedom from Torture is the only UK-based human rights organisation dedicated to the treatment and rehabilitation of torture survivors. We do this by offering services across England and Scotland to around 1,000 torture survivors a year, including psychological and physical therapies, forensic documentation of torture, legal and welfare advice, and creative projects. Since our establishment in 1985, more than 57,000 survivors of torture have been referred to us, and we are one of the world’s largest torture treatment centres. Our expert clinicians prepare medico-legal reports (MLRs) that are used in connection with torture survivors’ claims for international protection, and in research reports, such as this, aimed at holding torturing states to account. We are the only human rights organ- isation in the UK that systematically uses evidence from in-house clini- cians, and the torture survivors they work with, to hold torturing states accountable internationally; and to work towards a world free from torture. -

Torture's Link to Profit in Sri Lanka, a Retrospective Review

28 SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Mercy for money: Torture’s link to profit in Sri Lanka, a retrospective review Wendell Block, M.D.,* Jessica Lee M.D.,* Kera Vijayasingham B.A.* between 1989 and 2013. We tallied the Key points of interest: number of incidents in which claimants • This paper supplements earlier studies described paying cash or jewelry to end on prevalence of bribe payments to end torture, and collected other associated data torture in Sri Lanka, adding trends such as demographics, organizations of the throughout the war, after the war, perpetrators, locations, and, if available, involving multiple armed organizations, amounts paid. We included torture perpe- and across wide geographic locations. trated by both governmental and nongovern- • Victims may not genuinely be consid- mental militant groups. Collected data was ered to be a security risk but are used for coded and evaluated. Findings: We found extortion. that 78 of the 95 subjects (82.1%) whose • Significant economic and social impact reported ordeals met the United Nations on families is likely. Convention Against Torture/International • Torture unlikely to stop until financial Criminal Court definitions of torture incentives are removed. described paying to end torture at least once. • High prevalence suggests that perpetra- 43 subjects paid to end torture more than tors act in collusion with their superiors once. Multiple groups (governmental and and benefit from impunity. non-governmental) practiced torture and extorted money by doing so. A middleman Abstract was described in 32 percent of the incidents. Background: The purpose of this retro- Payment amounts as reported were high spective study is to describe the pattern of compared to average Sri Lankan annual bribe taking in exchange for release from incomes. -

“We Will Make You Regret Everything”

“We will make you Torture in Iran since regret everything” the 2009 elections Freedom from Torture Country Reporting Programme March 2013 Freedom from Torture Country Reporting Programme March 2013 “We will make you regret everything” Torture in Iran since the 2009 elections “Why did this happen to me, what did I do wrong? ...They’ve made me hate my body to a point that I don’t want to shower or get dressed... I feel alone and can’t trust another person.” Case study - Sanaz, page 6 3 Table of Contents Summary and key findings ............................................................. 7 Key findings of the report .................................................................... 8 Recommendations .......................................................................... 10 Introduction ................................................................................... 11 Freedom from Torture’s history of working with Iranian torture survivors 11 Case sample and method ..................................................................... 11 1. Case Profile ............................................................................................ 12 a. Place of origin and place of residence when detained .................................. 12 b. Ethnicity and religious identity .............................................................. 12 c. Ordinary occupation .......................................................................... 13 d. History of activism or dissent .............................................................. -

Mprof Thesis

Durham E-Theses Lives worthy of human dignity: investigating the impact of UK Asylum Policy on the well-being of asylum seekers in the North East of England. CARROLL, CHRISTINE How to cite: CARROLL, CHRISTINE (2013) Lives worthy of human dignity: investigating the impact of UK Asylum Policy on the well-being of asylum seekers in the North East of England., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8444/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Lives worthy of human dignity: investigating the impact of UK Asylum Policy on the well-being of asylum seekers in the North East of England. Chris Carroll January 2013 Thesis submitted for the award of Master of Professional Practice School of Applied Social Sciences Durham University Declaration I, Chris Carroll, declare that this thesis is my own work and the material included has not previously been submitted for a degree at this or any other university. -

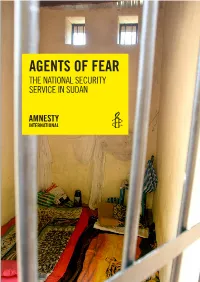

Agents of Fear

AGENTS OF FEAR THE NATIONAL SECURITY SERVICE IN SUDAN Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.8 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. Amnesty International Publications First published in 2010 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2010 Index: AFR 54/010/2010 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. Cover photo : A cell where detainees were held by the National Intelligence and Security Service in Nyala, Sudan. This photograph was taken in 2004 during a visit of -

The Development of a Torture Survivor Specific Measure of Change

19 SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Measuring change and changing measures: The development of a torture survivor specific measure of change Rebecca Horn, PhD, Andy Keefe* Abstract included in the clinical outcome tool. A Freedom from Torture is a UK-based process of discussion and testing of potential human rights organisation dedicated to the approaches led to the development of a draft treatment and rehabilitation of torture clinical outcome tool which was translated survivors. The organisation has been into 15 languages and then pilot tested with working towards the development of a 151 clients. clinical outcome tool for a number of years, The data from the pilot study was and the purpose of this paper is to (a) analysed and used to produce the final describe the process of developing the tool version of the clinical outcome tool. The and the final tool itself, and (b) to outline clinical outcome tool was formally rolled out the system which Freedom from Torture has across the organisation’s five centres in April established to collect, record and analyse the 2014. Clinicians working with adult clients data produced. have been completing it at the beginning of A review of the literature revealed that therapy and then again at regular intervals. existing measures were not appropriate for The data from the first year is currently measuring psychological and emotional being analysed, and the experiences of change amongst torture survivors; therefore clinicians, clients and interpreters of using the organisation undertook to develop a tool the clinical outcome tool are being reviewed, specifically designed for this target group. with a view to continuing to develop and The clinical outcome tool was developed improve the tool and the processes by which collaboratively by Freedom from Torture it is used. -

Trustees' Annual Report and Financial Statements

TRUSTEES’ ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2018 Freedom from Torture OUR VISION IS A WORLD FREE FROM TORTURE. IN A WORLD WHERE TORTURE STILL EXISTS, WE AIM TO ENSURE THAT THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF SURVIVORS ARE RESTORED THROUGH REHABILITATION AND PROTECTION. WE FIGHT TO ENSURE THAT STATES RESPONSIBLE FOR TORTURE ARE HELD TO ACCOUNT. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF TRUSTEES Our patron Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu describes the user engagement and survivor activism rooted in "lived experience". African concept of Ubuntu as a shared and common humanity We are thinking now about how we can support others to embrace summed up by the phrase “I am because you are”. A person with more participative methods and shift the balance of power towards Ubuntu is one with self-assurance who is open, available to others beneficiaries. We know that this engagement will also enrich our and affirms them. own practice through the benefits of mutual exchange. This sums up the ethos and values of Freedom from Torture – a I am very proud that we are playing a leading role in efforts to place of refuge, healing and hope rooted in respect for universal demonstrate how "hostile environment" policies in the UK are human rights, where we strive to be open, available, confident and impacting on asylum seekers and refugees including torture affirming while always being ready to listen and learn. survivors. This year also saw the publication of some immensely powerful research that put survivors’ voices and calls for change at Last year, our CEO Sonya Sceats led a huge exercise to review and the fore. -

“We Will Make You Regret Everything”

“We will make you Torture in Iran since the Registered charity no: England 1000340, Scotland SC039632 regret everything” 2009 elections Freedom from Torture Summary Version Country Reporting Programme March 2013 Freedom from Torture Country Reporting Programme March 2013 “We will make you regret everything” Torture in Iran since the 2009 elections Introduction Freedom from Torture (formerly known as the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture) is a UK- based human rights organisation and one of the world’s largest torture treatment centres. Since our foundation in 1985, more than 50,000 people have been referred to us for rehabilitation and other forms of care and practical assistance. In 2012 Freedom from Torture provided treatment services to more than 950 clients from around 80 different countries. In addition our independent medico-legal report service is commissioned to prepare between 300 and 600 medico-legal reports (MLRs) every year, for use mainly in UK asylum proceedings. Freedom from Torture seeks to protect and promote the rights of torture survivors by drawing on the evidence of torture that we have recorded over almost three decades. In particular, we aim to contribute to international efforts to prevent torture and hold perpetrator states to account through our Country Reporting Programme, based on research into torture patterns for particular countries, using evidence contained in our MLRs. ‘”We will make you regret everything” Torture in Iran since the 2009 elections’ is a study conducted by Freedom from Torture of 50 Iranian cases, forensically documented by clinicians in our Medico Legal Report Service, of torture perpetrated between 2009 and 2011. -

Proving Torture, Demanding the Impossible: Home Office Mistreatment of Medical Evidence

Proving Torture Demanding the impossible Home Office mistreatment of expert medical evidence November 2016 Freedom from Torture is the only UK-based human rights organisation dedicated to the treatment and rehabilitation of torture survivors. We do this by offering services across England and Scotland to around 1,000 torture survivors a year, including psychological and physical therapies, forensic documentation of torture, legal and welfare advice, and creative projects. Since our establishment in 1985, more than 57,000 survivors of torture have been referred to us, and we are one of the world’s largest torture treatment centres. Our expert clinicians prepare medico-legal reports (MLRs) that are used in connection with torture survivors’ claims for international protection, and in research reports, such as this. We are the only human rights organisation in the UK that systematically uses evidence from in-house clinicians, and the torture survivors they work with, to hold torturing states accountable internationally; and to work towards a world free from torture. To find out more about Freedom from Torture please visit www.freedomfromtorture.org Or follow us on Twitter@FreefromTorture Or join us on Facebook www.facebook.com/FreedomfromTorture Proving Torture Demanding the impossible Home Office mistreatment of expert medical evidence Cover photo: Survivor of Torture, by Jenny Matthews Title page photo: the scarred back of a 22-year-old Tamil man who is a survivor of sexual abuse and torture by Sri Lankan security forces while in detention ~ photo by Will Baxter FOREWORD Freedom from Torture must be congratulated for this excellent report. It clearly sheds light on what many of us working within the complex field of assessment of torture have been perturbed by for years - seemingly bizarre Home Office decisions in some asylum claims. -

Torture Survivors' Handbook

Torture Survivors’ Handbook Information and Resources for Torture Survivors in the UK Your rights to access support, advice and justice March 2015 Realised with the financial support of the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation 2 Contents Part 1: Introduction ........................................................... 5 i) Who this Handbook is for? .............................................. 5 ii) What information can I find in this Handbook? .............. 6 iii) What is Torture? ............................................................ 7 iv) Can REDRESS offer specialist advice?............................. 9 Part 2: Services and Assistance: What can I Expect? ......... 12 i) Medical and Social Support ........................................... 12 ii) British Nationals Tortured Abroad ................................ 20 iii) Torture by British officials Abroad ............................... 22 iv) Migrants Tortured Abroad ........................................... 24 Part 3: Seeking Justice: Obtaining Legal Advice and Moving Forward .......................................................................... 35 i) Making a Criminal Complaint against Perpetrators of Torture or Ill-Treatment .................................................... 38 ii) Bringing Complaints against the State for its Role in Serious Human Rights Abuses ........................................... 47 A. National Authorities .................................................. 47 B. International Human Rights Bodies .......................... 49 iii) Suing Torturers -

Methods for Addressing Ongoing Torture

P.O. Box 5675, Berkeley, CA 94705 USA METHODS FOR ADDRESSING ONGOING TORTURE Contact Information: Nuha Abusamra, Frank C. Newman Intern or Edith Coliver Intern Representing Human Rights Advocates through University of San Francisco School of Law International Human Rights Law Clinic Tel: 415-422-6961 [email protected] Professor Connie de la Vega [email protected] 1 Introduction State actors regularly violate international law without being held accountable for their violations. Consequently, survivors of torture have not been afforded adequate remedies. In order to ensure justice for torture survivors, there must be documentation of torture in order to promote transparency while simultaneously holding perpetrators of violence accountable. To ensure the effectiveness of the process, victims must be afforded access to legal remedies. The obligations against torture are set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,1 the Convention Against Torture,2 and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.3 This statement addresses the ongoing issue of torture by noting practices in four countries: the U.S., Syria, Iran, and Russia. I. The Need for Documentation In respect to the four countries mentioned above, there is a need for an impartial observance and documentation of state sponsored torture. In order to begin the transparency process, all states must first recognize the universal prohibition of torture and ill treatment pursuant to treaty obligations. This extends to “all places that the State party controls as a government authority.”4 1 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, U.N. Doc. A/810 (1948), Article 5, available at: http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/. -

Women's Asylum News

Issue 135 April/May 2016 Women’s Asylum News Women’s Project at Asylum Aid IN THIS ISSUE Pp. 2-4. Lead Article: Subscribe to “Time to Act” on double standards for sexual violence by Women’s Asylum Sonya Sceats, Freedom from Torture News Pp. 6. Sector Update: Victims of trafficking suffer long-term mental ill-health Women disproportionately affected in the Syrian refugee crisis and by the EU-Turkey refugee deal Donate Now and Pp. 7-8. National News: help us save lives! Immigration Bill to introduce a 72-hour time limit on the detention of pregnant women Pp. 8-9. International News: Lebanese authorities break sex trafficking ring exploiting Syrian women Refugee women from Djibouti hold hunger strike to protest rape and impunity Pp. 9-11. Publications: US: Transgender women abused in immigration detention UN Commission on the Status of Women: A mised opportunity Refugee Rights Data Project: Calais survey reveals women at risk Pp. 11-12 Events and Training FORWARD: Understanding FGM Film screening: Falling at each hurdle, credibility assesments in women’s asylum claims WGN: Recovery from sexual violence course Pp. 12-13 Charter Update: Still We Rise: WAST Roadshow Women’s Asylum News 134 (February/March 2016) 1 Lead Article The campaign has already achieved success, including adoption by the Home Office of a Women’s Asylum Action Plan containing a number of important commitments including a “Time to act” on double standards for sexual violence guarantee of a female interviewer to any woman who requests one at screening and inclu- On Tuesday 12 April, the Lords Select Committee on Sexual Violence in Conflict issued a pro- sion of information on the impact of trauma on memory in a new credibility training pro- gress report on the UK’s global sexual violence initiative.