Utah Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan Design Guide • Implementation and May Require Users to Redo Specific Tasks, Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 XTERRA COMPETITION RULES 1. Swim

2015 XTERRA COMPETITION RULES 1. Swim: 1.1. Wetsuits: are allowed based on water temperature measured the day prior to the event and confirmed the day of the event. Where water temperatures are close to limits, the decision will be made one hour before the start of the first swim. Pro/Elite Athletes: Wetsuits are allowed for pro athletes if the water temperature is below 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Centigrade). Age Group Athletes: Wetsuits are allowed for age group athletes if the water temperature is below 72 degrees Fahrenheit (22 degrees C) Mandatory Wetsuit: Wetsuits are mandatory below 57 degrees F (14 degrees C) Challenged Athletes: Wetsuits are allowed but not required at 1 any water temperature. Note: XTERRA follows the Swim Rules for Wetsuit Use established by the ITU at all XRC events. See Section D.2 in the ITU Competition Rules for specific details. Note: The XTERRA/ITU rules may be waived by the XPS race directors in favor of USA Triathlon Swimming Conduct rules. See Section 4 of the USA Triathlon Rules for specific details. o Note: If a race is governed by the USAT Article IV Swimming 2 Conduct rules – the following portion of Section 4.4 will apply: “When the water temperature is greater than 78 degrees, but less than 84 degrees Fahrenheit, age group participants may wear a wetsuit at their own discretion, provided however that participants who wear a wetsuit within this temperature range shall not be eligible for prizes or awards.” Specifically: the athlete will not be eligible for XTERRA Points. -

Refresh! Opening Hours out of School Holidays - Autumn/Winter Relax and Unwind Enjoy

Training Pool Programme Ice Rink Programme refresh! Opening Hours Out Of School Holidays - Autumn/Winter Relax and unwind Enjoy 22:00 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun While your children swim Public Ice Skating Ice Skating Curling Curling Curling Curling Skating Lessons Lessons Opening Times and Prices (10am - (8am - (8am - Masters Masters (Sauna and Steam Room – includes free swim) 21:00 12.30pm) 12.30pm) 12.30pm) Prices Crossfit ICE PREPARATION Autumn/Winter 2016/17 GASC Standard Public Public Public Fun Skating Adult £6.00 Aqua 20:00 Otters Curling Curling Curling Curling Session Skating Skating Aerobics (1pm - OAP/ Students £4.60 3.15pm) (1-3.30pm) (1-3pm) Set up Set I.A.S.C I.A.S.C I.A.S.C ICE PREPARATION Memberships available. Please contact Sub Aqua Lane swimming 19:00 Figure Lane Swimming Ice Skating Figure Lane swimming the Waterfront Fitness Gym on 01475 213 137 I.A.S.C I.A.S.C Skating Lessons Skating Lane swimming Curling Curling Curling Curling Club You must be 16 years and over to use sauna/steam room I.A.S.C (3.30pm - (3.15- 7.00pm) (3.45- 7.30pm) 6.45pm) Opening Hours: 18:00 ICE PREPARATION Mon-Fri 10am-9pm Sat-Sun 9am-4.30pm Ice Curling Curling Curling Curling Disco Closed Closed Club I.A.S.C (7-9pm) Offers Swim 17:00 Lessons Lessons Lessons Lessons Lessons Swimming Swimming Swimming Swimming Swimming Opening Hours During School Holidays including Public holidays Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 16:00 OpePublicning HPublicours Public Public Public Ice Skating Ice VSkatingisito r Prices Skating Skating Skating Skating Skating Lessons Lessons (10am- (10am- (10am- (10am- (10am- (8am- (8am- Leis12.30pm)ure Pool12.30pm) 12.30pm) 12.30pm) 12.00pm) 12.30pm) 12.30pm) During non-school term times and public holidays, 15:00 all activities are at the standard prices. -

Safety Tips for Having Fun on the Red & Sheyenne Rivers

Safety Tips for Having Fun on the Red & Sheyenne Rivers Boating/Canoeing/Kayaking/Fishing Water Safety is Your Responsibility!!! Canoeing, Kayaking and Boating • Stay sober. Never recreate on the river while Swimming/Wading under the influence of alcohol or drugs. • Swimming in the Red River is not • Children and adults should always wear a recommended. Personal Flotation Device (PFD)/life jacket that • If wading, wear a properly fitted and fastened fits properly and is fastened. Don’t assume you life jacket. have the swimming skills to keep you afloat, even the strongest swimmers can drown. Fishing • • Stay sober. Never recreate near the river while Do not paddle/boat alone. under the influence of alcohol or drugs. • Learn about your route in advance, including • Children and adults should always wear a potential hazards and current water conditions. Personal Flotation Device (PFD)/life jacket that • Portage around dams. fits properly and is fastened. Don’t assume you • Take a paddling/boating class. Learn the have the swimming skills to keep you afloat, essential canoeing/kayaking strokes to even the strongest swimmers can drown. effectively steer the vessel. • Be careful of slippery riverbanks. • Learn to swim. • Know where your fishing hooks are flying. (over) • Avoid situations that are beyond your paddling Dams and swimming ability. Seven of the eight dams on the U.S. portion of the • Have a safety plan. Red River have been retrofitted with a five percent slope rock rapid that has eliminated the undertow Carry a spare paddle. and allowed upstream fish migration. Still be Bring a whistle or sound-signaling device. -

Canoe Rescue Training Recovery and Re-Entry During COVID-19 Pandemic

Canoe Rescue Training Recovery and Re-entry during COVID-19 Pandemic Recommendations Submitted to Paddle Canada. Charles Burchill, Paul Shipman, Donna Kurt, Priscilla Haskin, Brian Johnston, Eric Gyselman Introduction Paddle Canada has provided information on running courses during the COVID-19 pandemic period which have been outlined on the Paddle Canada website. The typical techniques used for canoe rescues increase the likelihood of close contact and have not been well addressed in the canoeing program or Paddle Canada COVID-19 recommendations. Completing rescues is a critical canoeing skill even during this time, this document provides some additional information that might be helpful in the training of canoe rescues while minimizing proximity and contact. Most of the recommendations noted in this document are already practiced with regards to skills development and safety, but implementation may take some additional time and considerations. The skills outlined are consistent with the Paddle Canada Lake and Moving Water programs. This document is specific to canoe rescues (recovery and re-entry); there is already direction with regard to running overall courses during the COVID-19 pandemic period including: health assessment, location, physical distance, disinfection of equipment, and use of PPE. This document and associated material are specific to the modification and considerations related to canoe rescues. The end goal is to make the rescue more efficient and, in COVID-19 times, maintain physical distance. Considerations – Risk of exposure to the virus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, while executing a rescue - mitigation strategies (distancing, masks, gloves, sanitizer, other PPE). If the risk is high then the course will not run, or participants that are high risk (e.g. -

SWIMMING TEST for KAYAKING CLUB

SWIMMING TEST for KAYAKING CLUB To be able to check out Wittenberg kayaks, one must have passed a 4 hour kayak training class (two 2-hour sessions, one in the pool, second on the river), and to take that class, one must have first passed the following swimming test. The Swimming Test can be administered by any lifeguard at the pool, at any time the lifeguards are on duty, and not busy, during open swim hours. The swimmer must be able to: Satisfactory • swim four laps continuously, in the following styles o two laps freestyle, continuing on to [ ] o a third lap on one’s back, pausing to don a PFD, for a [ ] o fourth lap having donned a life-jacket (PFD) [ ] • swim at least half a length underwater (goggles ok) [ ] • float, on one’s back (30 secs), and also “deadman’s float (10 secs) [ ] • tread water in the deep end for two minutes, including: o raising hands out of water for 15 seconds [ ] o raising elbows out of water for 10 seconds [ ] o over-all treading time, of two minutes [ ] • retrieve a ‘brick’ from the bottom of the shallow end, 20 feet from the edge, and swim it back to the pool’s edge. Goggles ok, but no walking. [ ] Witnessed by: _________________________________ Date: ____________ (lifeguard, or test administrator) Signed by: _________________________________ Date: ____________ (swimmer) Please print name: ______________________________ Copies of this certification will be kept in the Kayak Club files, and also in the Boathouse Log, for quick reference, along with confirmation that one has passed the four-hour kayak basics class (2 hours in the pool, 2 hours on the river). -

Number of Steps Per Minute for Selected Activities

Number of steps per minute for selected activities Aerobics, high impact 203 Orienteering 260 Aerobics, low impact 145 Painting 131 Aerobics, step 246 Pilates 101 Badminton, casual 131 Ping pong 116 Badminton, competitive 203 Racquetball, casual 203 Basketball, game 230 Racquetball, competitive 290 Basketball, recreational 174 Raking leaves 125 Bicycling, leisurely 116 Roller skating 203 Bicycling, stationary 203 Rowing, light 101 Bowling 87 Rowing, moderate 203 Boxing 348 Running, 10 mph (6 min/mile) 463 Canoeing, light 87 Running, 8 mph (7.5 min mile) 391 Chopping wood, around home 174 Running, 6 mph (10 min mile) 290 Circuit Training 232 Running, 5 mph (12 min/mile) 232 Cross-country skiing, intense 260 Scuba diving 203 Cross-country skiing, moderate 232 Show shoveling 174 Cross-country skiing, slow 203 Snowboarding, light 150 Dancing 131 Snowboarding, moderate 182 Downhill skiing 174 Soccer, recreational 203 Elliptical trainer 203 Soccer, competitive 290 Firewood, carrying 145 Softball 145 Firewood, sawing with handsaw 217 Squash 348 Firewood, stacking 145 Stair climbing, machine 260 Football 260 Stair climbing, moderate 334 Gardening, light 116 Stair climbing, slow 232 Gardening, heavy 174 Stair climbing, vigorous 434 Gardening, weeding 131 Stretching 72 Golfing, without a cart 131 Swimming, backstroke 203 Golfing, with a cart 101 Swimming, breaststroke 290 Grocery Shopping 67 Swimming, butterfly 319 Handball 348 Swimming, freestyle 203 Hiking, 10-20 lb. load 217 Swimming, leisure 174 Hiking, 21-42 lb. load 232 Swimming, treading -

Helpful Terminology for Masters Swimmers

Fitness & Recreation Center bu.edu/fitrec | (617) 358-3750 Helpful Terminology for Masters Swimmers Many swimming terms are universal and some specific to BUMS. Here are some you might hear on deck. If you are new to swimming or BUMS, familiarize yourself with these terms and feel free to ask the coaches for clarification. Interval. Time to complete a swim of a certain distance. Rest time is included in the interval and varies in duration depending on the specific aims of the set. i.e., 4 x 200 on 3:00. This means that you have 3 minutes to complete 200 yards before you begin the next one. You push off to begin swim #2 at exactly 3:00, etc. Nearly all sets are done on either an interval or rest interval. Rest Interval (abr. RI). Rest time after a swim of a certain distance. i.e., 4 x 200 on 10s RI. This means that after you complete the first 200, you immediately look at the pace clock and begin the second 200 exactly 10 seconds later. If you touch the wall at 2:53, you push off for the next swim at 3:03. Nearly all sets are done on either an interval or rest interval. Base Interval (abr. Base or B). This term is used for freestyle repetitions of 100 yards unless otherwise specified. It is the interval at which you can swim a sustained aerobic effort for a prolonged distance 1000-2000 yards. It is not necessarily the fastest interval you can make, but one which challenges you while allowing you to remain in control of your swims. -

Flatwater Kayak Safety and Rescue (Sample Skills Course)

Flatwater Kayak Safety and Rescue (Sample Skills Course) Course Overview: The Flatwater Kayak Safety and Rescue workshop introduces essential flatwater safety practices and rescue techniques that can be performed with a minimum of equipment, in the first few minutes of an emergency. Course Objectives: Understand that prevention is the key to a safe trip. Understand how to avoid potential dangers. Develop and practice key self-rescue skills. Learn to focus on fast, simple, low-risk rescue techniques. Develop the skills to manage minor in-water incidents. Essential Eligibility Criteria (EEC): ACA courses are open to all individuals who acknowledge the ability to perform the following essential eligibility criteria. 1. Breathe independently (i.e., not require medical devices to sustain breathing) 2. Independently maintain sealed airway passages while under water 3. Independently hold head upright without neck / head support 4. Manage personal care independently or with assistance of a companion 5. Manage personal mobility independently or with a reasonable amount of assistance 6. Follow instructions and effectively communicate independently or with assistance of a companion 7. Independently turn from face-down to face-up and remain floating face up while wearing a properly fitted life jacket* 8. Get on / off or in / out of a paddlecraft independently or with a reasonable amount of assistance* 9. Independently get out and from under a capsized paddlecraft* 10. Remount or reenter the paddlecraft following deep water capsize independently or with a reasonable amount of assistance* 11. Maintain a safe body position while attempting skills, activities and rescues listed in the appropriate Course Outline, and have the ability to recognize and identify to others when such efforts would be unsafe given your personal situation* * To participate in adaptive programs, participants must acknowledge only the first six EEC listed above. -

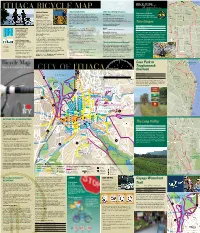

Bicycle Map Ithaca and Tompkins County 2016

ITHACA BICYCLE MAP BIKESuggestions RIDE Visitors Centers Bike-Friendly Events Other Local Biking Resources Finger Lakes Cycling Club What’s the best way to travel and enjoy your time in Bicycle Rentals East Shore Visitors Center Cue sheets for these suggested routes (800)284-8422 Ithaca and Tompkins County? By bike, of course! Check Contact the Visitors Center for information. and more available online at FLCycling.org 904 E. Shore Dr., Ithaca out all of these events around town that are bike-friendly and get ready for a fun filled ride around some of the city’s Cornell Bicycle and Pedestrian Website Our flagship visitors center is best music events, food festivals, fundraisers, and more! www.bike.cornell.edu, and the bike map is at your one-stop source for travel For complete event information, head to transportation.fs.cornell.edu/file/Bike_map_web-10.pdf information, activities, and events http://www.VisitIthaca.com Two Gorges in Ithaca, Tompkins County, the Bombers Bikes (Ithaca College) Finger Lakes Region and Spring www.ithaca.edu/orgs/bbikes Start: Taughannock State Park surrounding New York State. The self-service lobby, open Mileage: 28 miles Ithaca-Tompkins County 24/7, is stocked with maps and key information on accom- Streets Alive - StreetsAliveIthaca.com Way2Go www. www.ccetompkins.org/community/way2go Transportation Council modations, attractions and activities. Open year-round, Ithaca Festival - http://www.IthacaFestival.org Description: Moderate 121 East Court Street 6-7 days per week. Hours vary by season. Mountain Bike Information Summer This ride connects two of the outdoor jewels of our area Ithaca, New York 14850 Shindagin Hollow State Forest Phone: (607) 274-5570 Downtown Visitors Center –– Taughannock Falls State Park and Robert H. -

Coaching Swimmer with Disabilities

COACHING SWIMMERS WITH DISABILITIES Dave Denniston U.S. Paralympics Resident Program Coach [email protected] BRIEF HISTORY OF HOW I GOT INVOLVED MEMBER OF THE USA NATIONAL TEAM UNTIL 2004 ON FEBRUARY 6TH, 2005 I BROKE MY BACK SLEDDING STARTED SWIMMING AGAIN TO GET OUT OF MY WHEELCHAIR JIMI FLOWERS CONTACTED ME ABOUT COMPETING AGAIN I HAD SEVERAL MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT THE PARALYMPICS • No one competes for hugs • “Inspirational” and “Special” are dirty words • Competition is extremely intense EARNED A PLACE ON THE USA PARALYMPIC TEAM AND COMPETED IN BEIJING! JULY 10, 2009 JIMI FLOWERS DIES FROM CLIMBING ACCIDENT I APPLY FOR RESIDENT COACHING POSITION AND TAKE OVER WHERE JIMI LEFT OFF GETTING STARTED WITH A NEW ATHLETE • Learn everything you can about the athlete AND their disability • Parents are NOT always the best resource • Dive in!!! TRY EVERYTHING YOU CAN AS IF THEY WERE JUST ANOTHER SWIMMER • Then adapt for the disability FOCUS ON ATHLETICISM AND THE PERSON • NOT the disability • Try dryland exercises to develop athleticism in the water before they dry off and try them on land WRITE WORKOUTS AS YOU USUALLY WOULD, THEN MODIFY • Adjust intervals • Adjust distance • Similar exercise at same distance or speed (piston kick instead of scull) • Add equipment • With the right modifications a disabled swimmer will not hold the rest of the team back SEVERELY DISABLED ATHLETES WILL NEED MORE ONE-ON-ONE TRAINING AND COACHING • Make the time to make a difference • Very challenging, but equally rewarding • Make sure they are involved with the -

City of Lawrenceburg, Indiana Parks Department Pat O

CITY OF LAWRENCEBURG, INDIANA PARKS DEPARTMENT PAT O’NEILL MEMORIAL PARK SWIMMING POOL, SPLASH PARK, AND ICE SKATING RINK GUEST CODE OF SAFETY AND CONDUCT For your safety and enjoyment at our Park, please carefully read all of the text below. Failure to follow any of the regulations, conditions, or instructions set forth below may result in serious injury to yourself or other individuals. Individuals not following Park rules and safety instructions will be subject to immediate ejection from the Park without refund. Safety 1st! Safety is always #1 at the Park. Our goal is to accommodate all guests to enable them to fully enjoy our Park. Park Safety Standards – General Principles. Please understand that people may be excluded or removed from the Park in the interests of safety as determined by Park personnel. This may include, but is not limited to, concerns with sight-disabled people who need adequate eyesight to safely engage in an activity, height and weight restrictions, mobility and/or use and existence of all limbs in a stable and coordinated manner, a clear and alert mind which is unaffected by mental disability or other hindrance, being under the influence of any substances (whether legal or illegal, drugs or medications, alcohol, or any other chemicals and substances), signs of heat illness, any loose headwear or clothing or apparel which may damage property or pose a hazard to a guest or others, and whether or not a person may appear to be ill or injured or otherwise unable to safely participate. Swim and Skate at Your Own Risk! Although the Park has staff on site, including lifeguards for the swimming pool, any and all swimming, wading, diving, or other activity in or around the water, and any and all skating, walking, running, or activity on or around the ice rink is expressly AT YOUR OWN RISK. -

Report for Bainbridge Parks - Programs

Attachment D: Program Priorities Survey Responses Report for Bainbridge Parks - programs Response Counts Completion Rate: 100% Complete 78 Totals: 78 1 | Page | Attachment D 1 Attachment D: Program Priorities Survey Responses 1. What programs do you participate in? ResponseID Response 9 Discover Bainbridge walks Aqua exercise classes Tai chi chin class 10 Aquatic center swim lesson registration to earn swim licenses. Gymnastics (Rec Opt Team) Tennis @ BAC Summer camps (paddle camp, science, and forts) Adult Creative Writing with Margaret Nevinski 11 Aquatic center swim lesson registration to earn swim licenses. Gymnastics (Rec Opt Team) Tennis @ BAC Summer camps (paddle camp, science, and forts) Adult Creative Writing with Margaret Nevinski 12 n/a 14 Employee-Assistant MTB instructor 15 Avid mountainbiker and has done many mountain biking programs with park in the past 16 Volleyball Basketball Summer camps 19 Tennis, hiking, and mountain biking 20 Mountain Biking 21 We utilize our local parks, the pool, have rented various facilities and have utilized various park district programs especially for our daughter as she was growing up. Our most heavily utilized program is the gymnastic program which our daughter has been involved in since pre-school. 22 Our family participates in Hiking/Running/mountain biking on trails, tennis, basketball, softball, soccer, swimming in the Puget Sound off of the docks, beachcombing/hiking, and use of park boat ramps. 23 Youth Tennis 24 Tennis, swimming, sailing, golf, nature walks, biking. 25 Concerts in the park Adult education Youth education 26 pickle ball 27 Swim lessons, Family swim, open swim, lap swimming Gymnastics lessons Recreational soccer Kayaking Mountain biking Summer camps 28 Pickleball - almost daily and I am 69!! 29 Pickleball open play at Battle Point Park 6-10 hours/week 2 | Page | Attachment D 2 Attachment D: Program Priorities Survey Responses ResponseID Response 30 Pickleball at Battle Point.