Stony Brook University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

Building Cold War Warriors: Socialization of the Final Cold War Generation

BUILDING COLD WAR WARRIORS: SOCIALIZATION OF THE FINAL COLD WAR GENERATION Steven Robert Bellavia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Andrew M. Schocket, Advisor Karen B. Guzzo Graduate Faculty Representative Benjamin P. Greene Rebecca J. Mancuso © 2018 Steven Robert Bellavia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This dissertation examines the experiences of the final Cold War generation. I define this cohort as a subset of Generation X born between 1965 and 1971. The primary focus of this dissertation is to study the ways this cohort interacted with the three messages found embedded within the Cold War us vs. them binary. These messages included an emphasis on American exceptionalism, a manufactured and heightened fear of World War III, as well as the othering of the Soviet Union and its people. I begin the dissertation in the 1970s, - during the period of détente- where I examine the cohort’s experiences in elementary school. There they learned who was important within the American mythos and the rituals associated with being an American. This is followed by an examination of 1976’s bicentennial celebration, which focuses on not only the planning for the celebration but also specific events designed to fulfill the two prime directives of the celebration. As the 1980s came around not only did the Cold War change but also the cohort entered high school. Within this stage of this cohorts education, where I focus on the textbooks used by the cohort and the ways these textbooks reinforced notions of patriotism and being an American citizen. -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

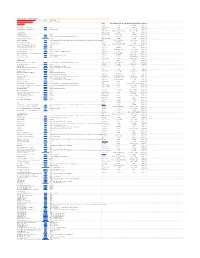

THANKSGIVING and BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always Do a Price Comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes

THANKSGIVING AND BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always do a price comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes KOHL's Coupon Codes: $15SAVEBIG15 Kohl's Cash 15% for everyoff through $50 spent 11/24 through 11/25 Electronics Store Thanksgiving Day Store HoursBlack Friday Store Hours Confirmed DVD PLAYERS AAFES Closed 4:00 AM Projected RCA 10" Dual Screen Portable DVD Player Walmart $59.00 Ace Hardware Open Open Confirmed Sylvania 7" Dual-Screen Portable DVD Player Shopko $49.99 Doorbuster Apple Closed 8 am to 10 pm Projected Babies"R"Us 5 pm to 11 pm on Friday Closes at 11 pm Projected BLU-RAY PLAYERS Barnes & Noble Closed Open Confirmed LG 4K Blu-Ray Disc Player Walmart $99.00 Bass Pro Shops 8 am to 6 pm 5:00 AM Confirmed LG 4K Ultra HD 3D Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $99.99 Deals online 11/24 at 12:01am, Doors open at 5pm; Only at Best Buy Bealls 6 pm to 11 pm 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed LG 4K Ultra-HD Blu-Ray Player - Model UP870 Dell Home & Home Office$109.99 Bed Bath & Beyond Closed 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung 4K Blu-Ray Player Kohl's $129.99 Shop Doorbusters online at 12:01 a.m. (CT) Thursday 11/23, and in store Thursday at 5 p.m.* + Get $15 in Kohl's Cash for every $50 SpentBelk 4 pm to 1 am Friday 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed Samsung 4K Ultra Blu-Ray Player Shopko $169.99 Doorbuster Best Buy 5:00 PM 8:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Blu-Ray Player with Built-In WiFi BJ's $44.99 Save 11/17-11/27 Big Lots 7 am to 12 am (midnight) 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Streaming 3K Ultra HD Wired Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $127.99 BJ's Wholesale Club Closed 7 am -

Sacred Music Volume 117 Number 3

SACRED MUSIC Volume 117, Number 3 (Fall) 1990 SACRED MUSIC Volume 117, Number 3, Fall 1990 FROM THE EDITORS Archbishop Annibale Bugnini 3 Copyright, a Moral Problem 4 The Demise of Gregoriana 5 CATHOLIC PRACTICES AND RECAPTURING THE SACRED 6 John M. Haas WILL BEAUTY LOOK AFTER HERSELF? 15 Giles R. Dimock, OP. THE TRAINING OF A CHURCH MUSICIAN 18 Monsignor Richard J. Schuler REVIEWS 21 NEWS 27 CONTRIBUTORS 28 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publications: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103. Editorial Board: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, Editor Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Rev. John Buchanan Harold Hughesdon William P. Mahrt Virginia A. Schubert Cal Stepan Rev. Richard M. Hogan Mary Ellen Strapp Judy Labon News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Musk for Review: Paul Salamunovich, 10828 Valley Spring Lane, N. Hollywood, Calif. 91602 Paul Manz, 1700 E. 56th St., Chicago, Illinois 60637 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Monsignor Richard J. Schuler Vice-President Gerhard Track General Secretary Virginia A. Schubert Treasurer Earl D. Hogan Directors Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Mrs. Donald G. Vellek William P. Mahrt Rev. Robert A. Skeris Membership in the CMAA includes a subscription to SACRED MUSIC. Voting membership, $12.50 annually; subscription membership, $10.00 annually; student membership, $5.00 annually. -

European Commission

6.1.2021 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Uni on C 4/1 II (Information) INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES EUROPEAN COMMISSION COMMON CATALOGUE OF VARIETIES OF AGRICULTURAL PLANT SPECIES Supplement 2021/1 (Text with EEA relevance) (2021/C 4/01) CONTENTS Page Legend . 3 List of agricultural species . 4 I. Beet 1. Beta vulgaris L. Sugar beet . 4 2. Beta vulgaris L. Fodder beet . 6 II. Fodder plants 5. Agrostis stolonifera L. Creeping bent . 8 6. Agrostis capillaris L. Brown top . 8 12. Dactylis glomerata L. Cocksfoot . 8 13. Festuca arundinacea Schreber Tall fescue . 8 15. Festuca ovina L. Sheep's fescue . 8 17. Festuca rubra L. Red fescue . 9 19. ×Festulolium Asch. et Graebn. Hybrids resulting from the crossing of a species of the genus Festuca with a species of the genus Lolium . 9 20. Lolium multiflorum Lam. Italian ryegrass (including Westerwold ryegrass) . 9 20.1. Ssp. alternativum . 9 20.2. Ssp. non alternativum . 9 21. Lolium perenne L. Perennial ryegrass . 10 22. Lolium x hybridum Hausskn. Hybrid ryegrass . 15 25. Phleum pratense L. Timothy . 15 29. Poa pratensis L. Smooth-stalked meadowgrass . 16 36. Lotus corniculatus L. Birdsfoot trefoil . 16 C 4/2 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union 6.1.2021 Page 37. Lupinus albus L. White lupin . 16 54. Pisum sativum L. (partim) Field pea . 16 63. Trifolium pratense L. Red clover . 18 64. Trifolium repens L. White clover . 18 71. Vicia faba L. (partim) Field bean . 19 73. Vicia sativa L. Common vetch . 20 75. -

Decoder Ring--Reprints and Refrigerators in "The American Comic Book (Critical Insights)" Jerry Spiller Art Institute of Charleston, [email protected]

Against the Grain Volume 27 | Issue 6 Article 43 2015 Decoder Ring--Reprints and Refrigerators in "The American Comic Book (Critical Insights)" Jerry Spiller Art Institute of Charleston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Spiller, Jerry (2015) "Decoder Ring--Reprints and Refrigerators in "The American Comic Book (Critical Insights)"," Against the Grain: Vol. 27: Iss. 6, Article 43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7256 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Decoder Ring — Reprints and Refrigerators in “The American Comic Book (Critical Insights)” Column Editor: Jerry Spiller (Art Institute of Charleston) <[email protected]> often lament that printed academic and schol- “Comic Fandom Through the Ages” sums up The essayists also note the lack of credit arly works lag behind online sources in time- changes in readership and the relationship and “larger than life” appeal afforded to even Iliness. To a degree, this is a simple necessity. between readers, creators, and the tone and positively portrayed female characters, as any I was pleasantly surprised in this regard subject matter and tone. The changes in both heroism or actual plot contributions they make when reading through the Salem Press volume fandom and creators detailed by Munson and are are often simply forgotten or overshadowed The American Comic Book, part of their Critical Helvie work well together to set up Katherine by the acts of male figures. -

The Mushroom

♥ STRAWBERRY ● THE QUEENDOM OF PLOMARI Published by The Cogan Dynasty, the country and queendom of Plomari www.artsetfree.com Awakening in Plomari was first began written in late 2017. It began to reach the internet on December 15, 2017, in unfinished format, updated as time went along. Copyright © William Bokelund 2o17- Fit for publication on gold and highly potent paper, as blessed by Jungfru Cecilia Mari Cogan To contact the authors go to their website www.artsetfree.com, or should the website for any reason be down, search the web. Loveletters to the authors are received with everwhelming joy Written by Cecillia Cogan, Spiros Cogan and th Butterflies of Plomari Spelling mistakes included for the magical benifit of the Queendom of Plomari and all Life, as the athors do not see these as mistakes but see them as magical messages from The Seamstress Who said we're not supposed to get excessive? 2 Go to the authors website at ArtSetFree.com For more books in the series 3 AWAKENING IN PLOMARI _______ You are a god, not a human being Cecilia Cogan Spiros Cogan & the Butterflies 4 CONTENTS SEX HERSELF IN HIGH PERSON 5 6 ike Cecilia, I now shut myself off from the evil world, with which I no longer want to have anything to do. I shall vanish. I will tell you of my L whereabouts in a Book of Love ~ King Spiros Cogan of Plomari 7 Bliss is the end, my Love. Come on now, comb home your victory. The mechanical human mind will never be satisfied anyway, only with Divine Love filling your heart will you ever feel satisfied. -

Hellboy in the Chapel of Moloch #1 (1 Shot) Blade of the Immortal Vol. 20 (OGN) Savage #1 (4 Issues) Soulfire Shadow Magic #0 (

H M ADVS AVENGERS V.7 DIGEST collects #24-27, $9 H ULT FF V. 11 TPB H SECRET WARS OMNIBUS collects #54-57, $13 collects #1-12 & MORE, $100 H ULT X-MEN V. 19 TPB H MMW ATLAS ERA JIM V.1 HC collects #94-97, $13 collects #1-10, $60 H MARVEL ZOMBIES TPB Hellboy in the Chapel of Moloch #1 (1 shot) H MMW X-MEN V. 7 HC collects #1-5, $16 Mike Mignola (W/A) and Dave Stewart © On the heels of the second Hellboy feature collects #67-80 LOTS MORE, $55 H MIGHTY AVENGERS V. 2 TPB film, legendary artist and Hellboy creator Mike Mignola returns to the drawing table H CIVIL WAR HC collects #7-11, $25 for this standalone adventure of the world’s greatest paranormal detective! Hellboy collects #1-7 & MORE $40 H investigates an ancient chapel in Eastern Europe where an artist compelled by some- SPIDEY BND V. 1 TPB thing more sinister than any muse has sequestered himself to complete his “life’s work.” H HALO UPRISING HC collects #546-551 & MORE, $20 collects #1-4 & SPOTLIGHT, $25 H X-MEN MESSIAH COMP TPB Blade of The Immortal vol. 20 (OGN) H HULK VOL 1 RED HULK HC collects #1-13 &MORE, $30 By Hiroaki Samura. The continuing tales of Manji and Rin. This picks up after the final collects #1-6 & WOLVIE #50, $25 H ANN CONQUEST BK 1 TPB issue #131. This is the only place to get new stories! Several old teams are reunited, a H IMM IRON FIST V.3 HC collects A LOT, $25 mind-blowing battle quickly starts and races us through most of this astonishing volume, and collects #7,15,16 & MORE, $25 H YOUNG AVENGERS PRESENTS TPB an old villain finally sees some pointed retribution at the hands of one of his prisoners! Let H INC HERCULES SI HC collects #1-6, $17 the breakout battle in the "Demon Lair" begin! collects #116-120, $20 H DAREDEVIL CRUEL & UNUSUAL TP H MI ILLIAD HC collects #106-110, $15 Spawn #185 (still on-going) collects #1-8, $25 H AMERCIAN DREAM TPB story TODD McFARLANE & BRIAN HOLGUIN art WHILCE PORTACIO & TODD H MS. -

Full Speed Ahead for DVD Sales by JILL KIPNIS Increase Another 49% in 2003

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) II.L.II..I.JJL.1I.1I.II.LJII I ILIi #BXNCCVR ******* ************** 3 -DIGIT 908 #908070EE374EM002# * BLBD 880 A06 B0105 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT APRIL 5, 2003 Patriotism Lifts Pro -War Songs; Chicks Suffer A Billboard and Airplay Moni- Last week, the Chicks' "Travelin' tor staff report Soldier," a record that many thought With the war in Iraq now more would become an anthem for the than a week old and displays of sup- troops in the event of war, instead port for the war increasing, went 1 -3 on the Billboard Linkin Park Enjoys Meteoric Opening radio responded on several Some Acts Nix Hot Country Singles & fronts. The biggest victims International Tracks chart in the wake BY LARRY FLICK Show by Eminem, which sold 1.3 million copies in of the patriotic surge have Tours In Light of singer Natalie Maims' NEW YORK -Based on first -day sales activity for its its first full week of sales for the week ending June been Dixie Chicks, whose Of War: anti -war/anti -President new album, Meteora, Linkin Park could enjoy the 2, 2002, according to Nielsen SoundScan. Seven - tracks suffered major air- See Page 7 Bush comments (Bill- first 1 million -selling week of 2003. Early estimates day sales of more than 900,000 units would score play losses at their host for- board, March 29). -

Assessing Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, Lucky Dube and Alpha Blondy

humanities Article Political Messages in African Music: Assessing Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, Lucky Dube and Alpha Blondy Uche Onyebadi Department of Journalism, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX 76129, USA; [email protected] Received: 30 September 2018; Accepted: 30 November 2018; Published: 6 December 2018 Abstract: Political communication inquiry principally investigates institutions such as governments and congress, and processes such as elections and political advertising. This study takes a largely unexplored route: An assessment of political messages embedded in music, with a focus on the artistic works of three male African music icons—Fela Anikulapo-Kuti (Nigeria), Lucky Dube (South Africa), and Alpha Blondy (Côte d’Ivoire). Methodologically, a purposive sample of the lyrics of songs by the musicians was textually analyzed to identify the themes and nuances in their political messaging. Framing was the theoretical underpinning. This study determined that all three musicians were vocal against corruption, citizen marginalization, and a cessation of wars and bloodshed in the continent. Keywords: Political communication; African politics; African music; Fela Anikulapo-Kuti; Alpha Blondy; Lucky Dube; textual analysis 1. Introduction Music permeates significant aspects of African society, culture, and tradition. Adebayo(2017, p. 56) opined that “to the African, music is not just a pastime, it is a ritual” that describes the true essence and humaneness in being of African origin. Cudjoe(1953, p. 280) description of the place of music among the Ewe people in Ghana typifies this African musical heritage. He observed that “music has an important place in the social life of the Ewe people. There is no activity which does not have music appropriate to it: weaver, farmer and fisherman each sings in perfect time to the rhythmic movement of (one’s) craft .. -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 4-1-2008 SFRA ewN sletter 284 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 284 " (2008). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 98. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/98 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • Spring 2008 Editors I Karen Hellekson 16 Rolling Rdg. Jay, ME 04239 [email protected] [email protected] SFRA Review Business SFRA Review Institutes New Feature 2 Craig Jacobsen English Department SFRA Business Mesa Community College SFRA in Transition 2 1833 West Southern Ave. SFRA Executive Board Meeting 2 Mesa, AZ 85202 2008 Program Committee Update 3 [email protected] 2008 Clareson Award 3 [email protected] 2008 Pilgrim Award 4 2008 Pioneer Award 4 Feature Article: 101 Managing Editor Comics Studies 101 4 Janice M. Bogstad Feature Article: One Course McIntyre Library-CD PKD Lit and Film 7 University ofWisconsin-Eau Claire 105 Garfield