Natural and Unnatural Selection in a Wild Goose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Snow Goose EN

Introduction This bird • has evolved a strong serrated bill and tongue to cut and tear the roots of bulrushes and sedges • often has a rusty orange face, because its feathers have been stained by iron in the earth where the bird feeds • is probably the most abundant goose in Canada • unlike most other waterfowl, usually nests in large colonies with densities of up to 2 000 pairs per square kilometre Description The Lesser Snow Goose Chen caerulescens caerulescens has two different appearances, white phase and blue phase. The plumage of white-phase geese is almost completely white, except for black wing tips. The blue-phase goose has a white head, a bluish colour on the feathers of the lower back and flanks, and a body that ranges in colour from very pale, almost white, to very dark. Both the white- and blue-phase snow geese frequently have rusty orange faces, because their feathers have been stained by iron in the earth where the birds feed. The downy goslings of the white-phase geese are yellow, those of the blue phase nearly black. By two months of age the young birds of both colour phases are grey with black wing tips, although the immature blue-phase birds are generally a darker grey and have some light feathers on the chin and throat, which can become stained like those of the adults. The goslings have mostly lost their grey coloring by the following spring; in April and May they may only show a few flecks of darker coloring on their head and neck, and a few grey feathers on their wings that distinguish them from adults. -

Homestead Poultry Feed Brochure

PREMIUM QUALITY NUTRITION ® Mankato, MN 56001 www.HomesteadPoultryFeed.com www.facebook.com/homesteadpoultryfeeds W5191 Formulated to Produce Top-Quality Birds DUCKS & GEESE Waterfowl need somewhat less heat than chickens. In their rst week of life, their environment should be heated to 90º F. This temperature can be lowered in ve-degree increments each week until their fth week, after which they are usually ready to live without supplemental heat. Bedding Do not use wood shavings for birds less than two weeks old, as they are more likely to consume the shavings and get blocked up. Try to avoid using slick surfaces like newspapers; if you must use them, spread paper towels over the newspapers for the rst few days. Since they are so unsteady at rst, goslings are prone to a condition called splay-leg, or spraddle legs, so it is important for them to have good footing immediately after hatching. During warm weather, spending some time walking on grass each day can be very good for their legs — plus, they'll begin eating grass. Water A constant supply of fresh water is necessary for ducklings and goslings. For the rst week, a chick waterer works well. After that, however, they are too large to submerge their heads and clean their faces in the water, which all waterfowl must be able to do. ® Avoid using a bowl of water. Here’s why: First, ducklings and goslings may walk in their drinking water and/or leave droppings in it. Second, if they stay wet, they may catch a fatal cold. Provide a waterer that is deep enough for older ducklings and goslings Homestead Poultry Feeds to submerge their heads in but not deep enough for them to get inside or tip over. -

Incubating and Hatching Eggs

EPS-001 7/13 Incubating and Hatching Eggs Gregory S. Archer and A. Lee Cartwright* hether eggs come from a common chicken Factors that affect hatchability or an exotic bird, you must store and incu- W Breeder Hatchery bate them carefully for a successful hatch. Envi- Breeder nutrition Sanitation ronmental conditions, handling, sanitation, and Disease Egg storage record keeping are all important factors when it Mating activity Egg damage comes to incubating and hatching eggs. Egg damage Incubation—Management of Correct male and female setters and hatchers Fertile egg quality body weight Chick handling A fertile egg is alive; each egg contains living cells Egg sanitation that can become a viable embryo and then a chick. Egg storage Eggs are fragile and a successful hatch begins with undamaged eggs that are fresh, clean, and fertile. Collecting and storing fertile eggs You can produce fertile eggs yourself or obtain Fertile eggs must be collected carefully and stored them elsewhere. While commercial hatcheries properly until they are incubated. Keeping the produce quality eggs that are highly fertile, many eggs at proper storage temperatures keeps the do not ship small quantities. If you mail order embryo from starting and stopping development, eggs, be sure to pick them up promptly from your which increases embryo mortality. Collecting receiving area. Hatchability will decrease if eggs eggs frequently and storing them properly delays are handled poorly or get too hot or too cold in embryo development until you are ready to incu- transit. bate them. If you produce the eggs on site, you must care for the breeding stock properly to ensure maximum Egg storage reminders fertility. -

Than a Meal: the Turkey in History, Myth

More Than a Meal Abigail at United Poultry Concerns’ Thanksgiving Party Saturday, November 22, 1997. Photo: Barbara Davidson, The Washington Times, 11/27/97 More Than a Meal The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality Karen Davis, Ph.D. Lantern Books New York A Division of Booklight Inc. Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright © Karen Davis, Ph.D. 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data For Boris, who “almost got to be The real turkey inside of me.” From Boris, by Terry Kleeman and Marie Gleason Anne Shirley, 16-year-old star of “Anne of Green Gables” (RKO-Radio) on Thanksgiving Day, 1934 Photo: Underwood & Underwood, © 1988 Underwood Photo Archives, Ltd., San Francisco Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgments . .9 Introduction: Milton, Doris, and Some “Turkeys” in Recent American History . .11 1. A History of Image Problems: The Turkey as a Mock Figure of Speech and Symbol of Failure . .17 2. The Turkey By Many Other Names: Confusing Nomenclature and Species Identification Surrounding the Native American Bird . .25 3. A True Original Native of America . .33 4. Our Token of Festive Joy . .51 5. Why Do We Hate This Celebrated Bird? . .73 6. Rituals of Spectacular Humiliation: An Attempt to Make a Pathetic Situation Seem Funny . .99 7 8 More Than a Meal 7. -

Waterfowl Management in Georgia

WATERFOWL MANAGEMENT IN GEORGIA PREFACE & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Wildlife biologists serving on the Georgia Department of Natural Resources' Waterfowl Committee prepared the information found here. It is intended to serve as a source of general information for those with a casual interest in waterfowl. It also serves as a more detailed guide for landowners and managers who want to improve the waterfowl habitat on their property. The committee hopes this information will serve to benefit the waterfowl resource in Georgia and help to ensure its well- being for generations to come. Land management assistance is available from Wildlife Resources Division biologists. For additional help, contact the nearest Game Management Section office. Game Management Offices Region I Armuchee (706) 295-6041 Region II Gainesville (770) 535-5700 Region III Thomson (706) 595-4222 Region III Thomson (Augusta) (706) 667-4672 Region IV Fort Valley (478) 825-6354 Region V Albany (229) 430-4254 Region VI Fitzgerald (229) 426-5267 Region VII Brunswick (912) 262-3173 * Headquarters (770) 918-6416 We would like to express our appreciation to Carroll Allen and Dan Forster of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources for providing editorial comments. AUTHORS: Greg Balkcom, Senior Wildlife Biologist Ted Touchstone, Wildlife Biologist Kent Kammermeyer, Senior Wildlife Biologist Vic Vansant, Regional Wildlife Supervisor Carmen Martin, Wildlife Biologist Mike Van Brackle, Wildlife Biologist George Steele, Wildlife Biologist John Bowers, Senior Wildlife Biologist The Department of Natural Resources is an equal opportunity employer and offers all persons the opportunity to compete and participate in areas of employment regardless of race, color, religion, national origin, handicap, or other non-merit factors. -

Lesser Snow Goose

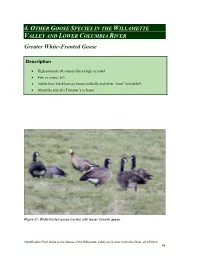

4. OTHER GOOSE SPECIES IN THE WILLAMETTE VALLEY AND LOWER COLUMBIA RIVER Greater White-Fronted Goose Description • High-pitched call, sounds like a laugh or yodel. • Pink or orange bill. • Adults have black bars on breast and belly and white “front” behind bill. • About the size of a Taverner’s or lesser. Figure 97: White-fronted goose (center) with lesser Canada geese. Identification Field Guide to the Geese of the Willamette Valley and Lower Columbia River, 2nd Edition 65 Figure 98: White-fronted geese (three in foreground) and cackling geese. Figure 99: White-fronted geese. Identification Field Guide to the Geese of the Willamette Valley and Lower Columbia River, 2nd Edition 66 Figure 100: White-fronted geese; adults have black markings on belly; juveniles lack marks. Figure 101: White-fronted geese in flight; they are similar to lesser Canada geese in size. Identification Field Guide to the Geese of the Willamette Valley and Lower Columbia River, 2nd Edition 67 Figure 102: Juvenile white-fronted goose (left) with adult white-fronts. Figure 103: Adult white-fronted geese in flight. Identification Field Guide to the Geese of the Willamette Valley and Lower Columbia River, 2nd Edition 68 History Populations of greater white-fronted geese, commonly known as specs or speckle bellies, found in the Pacific Flyway have fluctuated for the past several decades. Currently, the Pacific population is increasing and is above flyway management objectives. Most white-fronted geese winter in the Central Valley of California, but white-fronts are observed and harvested in the permit zone every year. Currently, they are not common in our region, but appear to be increasing. -

Waterfowl in Iowa, Overview

STATE OF IOWA 1977 WATERFOWL IN IOWA By JACK W MUSGROVE Director DIVISION OF MUSEUM AND ARCHIVES STATE HISTORICAL DEPARTMENT and MARY R MUSGROVE Illustrated by MAYNARD F REECE Printed for STATE CONSERVATION COMMISSION DES MOINES, IOWA Copyright 1943 Copyright 1947 Copyright 1953 Copyright 1961 Copyright 1977 Published by the STATE OF IOWA Des Moines Fifth Edition FOREWORD Since the origin of man the migratory flight of waterfowl has fired his imagination. Undoubtedly the hungry caveman, as he watched wave after wave of ducks and geese pass overhead, felt a thrill, and his dull brain questioned, “Whither and why?” The same age - old attraction each spring and fall turns thousands of faces skyward when flocks of Canada geese fly over. In historic times Iowa was the nesting ground of countless flocks of ducks, geese, and swans. Much of the marshland that was their home has been tiled and has disappeared under the corn planter. However, this state is still the summer home of many species, and restoration of various areas is annually increasing the number. Iowa is more important as a cafeteria for the ducks on their semiannual flights than as a nesting ground, and multitudes of them stop in this state to feed and grow fat on waste grain. The interest in waterfowl may be observed each spring during the blue and snow goose flight along the Missouri River, where thousands of spectators gather to watch the flight. There are many bird study clubs in the state with large memberships, as well as hundreds of unaffiliated ornithologists who spend much of their leisure time observing birds. -

American Museum Novitiates 3885, 28Pp

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Number 3885, 28 pp. October 24, 2017 Polar bear foraging behavior during the ice-free period in western Hudson Bay: observations, origins, and potential significance LINDA J. GORMEZANO,1 SUSAN N. ELLIS-FELEGE,2 DAVID T. ILES,3 ANDREW BARNAS,2 AND ROBERT F. ROCKWELL1 ABSTRACT During much of the year, polar bears in western Hudson Bay use energy-conserving hunt- ing tactics, such as still-hunting and stalking, to capture seals from sea-ice platforms. Such hunting allows these bears to accumulate a majority of the annual fat reserves that sustain them on land through the ice-free season. As climate change has led to earlier spring sea-ice breakup in western Hudson Bay, polar bears have less time to hunt seals, especially seal pups in their spring birthing lairs. Concerns have been raised as to whether this will lead to a shortfall in the bears’ annual energy budget. Research based on scat analyses indicates that over the past 40 years at least some of these polar bears eat a variety of food during the ice-free season and are opportunistically taking advantage of a changing and increasing terrestrial prey base. Whether this food will offset anticipated shortfalls and whether land-based foraging will spread through- out the population is not yet known, and full resolution of the issues requires detailed physi- ological and genetic research. For insight on these issues, we present detailed observations on polar bears hunting without an ice platform. We compare the hunting tactics to those of polar bears using an ice platform and to those of the closely related grizzly bear. -

2019 Waterfowl Population Status Survey

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Waterfowl Population Status, 2019 Waterfowl Population Status, 2019 August 19, 2019 In the United States the process of establishing hunting regulations for waterfowl is conducted annually. This process involves a number of scheduled meetings in which information regarding the status of waterfowl is presented to individuals within the agencies responsible for setting hunting regulations. In addition, the proposed regulations are published in the Federal Register to allow public comment. This report includes the most current breeding population and production information available for waterfowl in North America and is a result of cooperative eforts by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), various state and provincial conservation agencies, and private conservation organizations. In addition to providing current information on the status of populations, this report is intended to aid the development of waterfowl harvest regulations in the United States for the 2020–2021 hunting season. i Acknowledgments Waterfowl Population and Habitat Information: The information contained in this report is the result of the eforts of numerous individuals and organizations. Principal contributors include the Canadian Wildlife Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, state wildlife conservation agencies, provincial conservation agencies from Canada, and Direcci´on General de Conservaci´on Ecol´ogica de los Recursos Naturales, Mexico. In addition, several conservation organizations, other state and federal agencies, universities, and private individuals provided information or cooperated in survey activities. Appendix A.1 provides a list of individuals responsible for the collection and compilation of data for the “Status of Ducks” section of this report. -

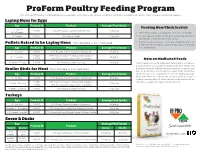

Proform Poultry Feeding Program

ProForm Poultry Feeding Program This ProForm® Poultry Feeding Program is available at Hi-Pro Feeds’ dealers in British Columbia excluding the Peace River and East Kootenay regions. Laying Hens for Eggs Age Product ID Product Average Feed Intake Feeding Hen/Chick Scratch 1st egg or 190481 18% All Purpose Laying Poultry Pellets 105 g/day 18 - 40 weeks • Hen/Chick Scratch is a mixture of corn, oats and wheat. 40+ weeks 190641 16% Laying Pellets 115 g/day • It is not a balanced diet, and birds may develop nutritional deficiencies if they are fed scratch alone. Pullets Raised to be Laying Hens (*also available in non-medicated) • Scratch can be used as a treat, but should be fed at no more than 5% of the bird’s daily diet (ex: max of 5-6 g/day Age Product ID Product Average Feed Intake for a mature hen). 0 - 6 weeks 190101 *22% Poultry Starter Crumbles (Medicated) 35 g/day 190461 18% Poultry Grower Crumbles (Medicated) or 6 - 14 weeks 65 g/day 190301 18% All Purpose Laying Poultry Crumbles Note on Medicated Feeds 14 weeks - 1st egg 190751 16% Poultry Grower Crumbles 75 g/day Poultry feeds containing medication help prevent coccidiosis, a disease which can cause lost productivity, poor health and Broiler Birds for Meat (*also available in non-medicated) mortality in your flock. Birds build immunity to coccidiosis over time so medication is not required in older birds. Medication Age Product ID Product Average Feed Intake should not be fed to laying hens that are producing eggs. Read and follow the instructions on your feed tag if you’re 0 - 21 days 190101 *22% Poultry Starter Crumbles (Medicated) 50 g/day feeding a medicated feed. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of Anseriformes Based on Mitochondrial DNA Analysis

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23 (2002) 339–356 www.academicpress.com A molecular phylogeny of anseriformes based on mitochondrial DNA analysis Carole Donne-Goussee,a Vincent Laudet,b and Catherine Haanni€ a,* a CNRS UMR 5534, Centre de Genetique Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Universite Claude Bernard Lyon 1, 16 rue Raphael Dubois, Ba^t. Mendel, 69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France b CNRS UMR 5665, Laboratoire de Biologie Moleculaire et Cellulaire, Ecole Normale Superieure de Lyon, 45 Allee d’Italie, 69364 Lyon Cedex 07, France Received 5 June 2001; received in revised form 4 December 2001 Abstract To study the phylogenetic relationships among Anseriformes, sequences for the complete mitochondrial control region (CR) were determined from 45 waterfowl representing 24 genera, i.e., half of the existing genera. To confirm the results based on CR analysis we also analyzed representative species based on two mitochondrial protein-coding genes, cytochrome b (cytb) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2). These data allowed us to construct a robust phylogeny of the Anseriformes and to compare it with existing phylogenies based on morphological or molecular data. Chauna and Dendrocygna were identified as early offshoots of the Anseriformes. All the remaining taxa fell into two clades that correspond to the two subfamilies Anatinae and Anserinae. Within Anserinae Branta and Anser cluster together, whereas Coscoroba, Cygnus, and Cereopsis form a relatively weak clade with Cygnus diverging first. Five clades are clearly recognizable among Anatinae: (i) the Anatini with Anas and Lophonetta; (ii) the Aythyini with Aythya and Netta; (iii) the Cairinini with Cairina and Aix; (iv) the Mergini with Mergus, Bucephala, Melanitta, Callonetta, So- materia, and Clangula, and (v) the Tadornini with Tadorna, Chloephaga, and Alopochen. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose