Sharing Economy’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transportation Technologies, Sharing Economy, and Teleactivities: Implications for Built Environment and Travel

Transportation Research Part D 92 (2021) 102716 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part D journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/trd Transportation technologies, sharing economy, and teleactivities: Implications for built environment and travel Kostas Mouratidis a,*, Sebastian Peters a, Bert van Wee b a Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Landscape and Society, Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU), Ås, Norway b Transport and Logistics Group, Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This paper reviews how teleactivities, the sharing economy, and emerging transportation tech Emerging mobility nologies – components of what we could call the “App City” – may influencetravel behavior and Information and communications technology the built environment. Findings suggest that teleactivities may substitute some trips but generate (ICT) others. Telework and teleconferencing may reduce total travel. Findings on the sharing economy Urban form suggest that accommodation sharing increases long-distance travel; bikesharing is conducive to Smart cities Literature review more active travel and lower car use; carsharing may reduce private car use and ownership; Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic ridesourcing (ridehailing) may increase vehicle miles traveled; while the implications of e-scooter sharing, ridesharing, and Mobility as a Service are context-dependent. Findings on emerging transportation -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Sectoral Evolution and Shifting Service Delivery Models in the Sharing Economy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Mahmuda, S.; Sigler, T.; Knight, E.; Corcoran, J. Article Sectoral evolution and shifting service delivery models in the sharing economy Business Research Provided in Cooperation with: VHB - Verband der Hochschullehrer für Betriebswirtschaft, German Academic Association of Business Research Suggested Citation: Mahmuda, S.; Sigler, T.; Knight, E.; Corcoran, J. (2020) : Sectoral evolution and shifting service delivery models in the sharing economy, Business Research, ISSN 2198-2627, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 13, Iss. 2, pp. 663-684, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40685-020-00110-4 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/233176 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If -

The New England College of Optometry Peer to Peer (P2P) Policy

The New England College of Optometry Peer To Peer (P2P) Policy Created in Compliance with the Higher Education Opportunity Act (HEOA) Peer-to-Peer File Sharing Requirements Overview: Peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing applications are used to connect a computer directly to other computers in order to transfer files between the systems. Sometimes these applications are used to transfer copyrighted materials such as music and movies. Examples of P2P applications are BitTorrent, Gnutella, eMule, Ares Galaxy, Megaupload, Azureus, PPStream, Pando, Ares, Fileguri, Kugoo. Of these applications, BitTorrent has value in the scientific community. For purposes of this policy, The New England College of Optometry (College) refers to the College and its affiliate New England Eye Institute, Inc. Compliance: In order to comply with both the intent of the College’s Copyright Policy, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and with the Higher Education Opportunity Act’s (HEOA) file sharing requirements, all P2P file sharing applications are to be blocked at the firewall to prevent illegal downloading as well as to preserve the network bandwidth so that the College internet access is neither compromised nor diminished. Starting in September 2010, the College IT Department will block all well-known P2P ports on the firewall at the application level. If your work requires the use of BitTorrent or another program, an exception may be made as outlined below. The College will audit network usage/activity reports to determine if there is unauthorized P2P activity; the IT Department does random spot checks for new P2P programs every 72 hours and immediately blocks new and emerging P2P networks at the firewall. -

English Renaissance Dream Theory and Its Use in Shakespeare

THE RICE INSTITUTE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE DREAM THEORY MID ITS USE IN SHAKESPEARE By COMPTON REES, JUNIOR A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Houston, Texas April, 1958 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .............. 1-3 Chapter I Psychological Background: Imagination and Sleep ............................... 4-27 Chapter II Internal Natural Dreams 28-62 Chapter III External Natural Dreams ................. 63-74 Chapter IV Supernatural Dreams ...................... 75-94 Chapter V Shakespeare’s Use of Dreams 95-111 Bibliography 112-115 INTRODUCTION This study deals specifically with dream theories that are recorded in English books published before 1616, the year of Shakespeare1s death, with a few notable exceptions such as Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). Though this thesis does not pretend to include all available material on this subject during Shakespeare*s time, yet I have attempted to utilise all significant material found in the prose writings of selected doctors, theologians, translated Latin writers, recognised Shakespeare sources (Holinshed, Plutarch), and other prose writers of the time? in a few poets; and in representative dramatists. Though some sources were not originally written during the Elizabethan period, such as classical translations and early poetry, my criterion has been that, if the work was published in English and was thus currently available, it may be justifiably included in this study. Most of the source material is found in prose, since this A medium is more suited than are imaginative poetry anl drama y:/h to the expository discussions of dreams. The imaginative drama I speak of here includes Shakespeare, of course. -

Vol. 3, ,2017-2018

Vol. 3, ,2017-2018 1 Page 1 From the Secretary’s Desk, Shri. S. Ravindran I am glad to know that the Department of Management Studies of our institution is bringing out the third volume of newsletter covering the events of the academic year 2017-2018. In addition to being a compilation of the events that took place in the department, it would be good if the Newsletter provides a platform for knowledge transformation among the faculty and the students. I wish the venture all success. From the Principal’s Desk Dr. D. Valavan Being distinctive in delivering Management Education for more than a decade, Department of Management Studies, Saranathan College of Engineering is perpetually imparting knowledge to Management aspirants for meeting new challenges which they face in Corporate Arena. Our distinguished Faculty members are transforming the Knowledge with our traditional Value Systems and Culture. Not only in academics, but also in educating the Management Professionals to manage themselves well and to conduct themselves well wherever they go to serve the needs of the industry and the society, to be ethical and morally responsible so that they become indispensable managers and administrators and an asset to the society. I am very happy that the Department of Management Studies is bringing out the third volume of newsletter for the period 2017-18, which will give a glimpse of the activities of the department in one fold. I wish the Department of Management Studies escalates to greater heights enlisting the utmost cooperation of the students whose growth is of paramount priority to us. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 603 7 December 2015 No. 83 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 7 December 2015 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2015 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 687 7 DECEMBER 2015 688 Mr Duncan Smith: By the way, I welcome the hon. House of Commons Gentleman back. It is good to see him back in his place; I understand he has had some difficulties with health treatments. Monday 7 December 2015 The hon. Gentleman would be right, if that were the trend and the direction in which we were going. It is interesting that there is a difference between us and the The House met at half-past Two o’clock United States. The vast majority of the jobs that have been created here are white-collar and full-time. That is PRAYERS important. Although we think that people being self- employed is excellent for those who choose to do it, we are seeing a huge trend in supported jobs with full pay [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] and full-time work. Dr Eilidh Whiteford (Banff and Buchan) (SNP): The Oral Answers to Questions selling point of the Government’s universal credit scheme was that it was supposed to increase work incentives. However, the reduction in work allowances in universal credit due to take effect in April next year will leave WORK AND PENSIONS around 35,000 working households with no transitional protection and thousands of pounds worse off. -

Effects of Generic Strategies on the Competitive Advantage of Firms in Kenya’S Airline Industry: a Survey of Selected Airlines

EFFECTS OF GENERIC STRATEGIES ON THE COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE OF FIRMS IN KENYA’S AIRLINE INDUSTRY: A SURVEY OF SELECTED AIRLINES BY RUTH MORAA OMWOYO UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY AFRICA FALL, 2016 EFFECTS OF GENERIC STRATEGIES ON THE COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE OF FIRMS IN KENYA’S AIRLINE INDUSTRY: A SURVEY OF SELECTED AIRLINES BY RUTH MORAA OMWOYO A Research Project Report Submitted to the Chandaria School of Business in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Masters in Business Administration (MBA) UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY – AFRICA FALL, 2016 STUDENT’S DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare this my original work and has not been submitted to any other college, institution or university other than United States International University-Africa for academic credit. Signed _________________________ Date: _________________________ Ruth Moraa Omwoyo (ID No: 645630) This project report has been presented for examination with my approval as the appointed supervisor. Signed ___________________________ Date: _________________________ Dr. Juliana M. Namada Signed: __________________________ Date: _________________________ Dean Chandaria School of Business ii COPYRIGHT © 2016 Ruth Moraa Omwoyo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Any unauthorized reprint or use of this research report is prohibited. No part of the study may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without express written permission from the author and the university. iii ABSTRACT The purpose of the study was to examine the effects of generic strategies on competitive advantage on firms in Kenya’s airline industry. It focused on selected airlines. This study aimed at establishing how cost leadership strategy affect competitive advantage, determining how differentiation strategy affect competitive advantage and examining how focus strategy affect competitive advantage of firms in Kenya’s airline industry. -

Case Study: the Uberisation of Supply Chain

ISSN (Print) : 2249-1880 SAMVAD: SIBM Pune Research Journal, Vol X, 26-31, June 2016 ISSN (Online) : 2348-5329 Case Study: The Uberisation of Supply Chain Venkatesh Ganapathy* Associate Professor, Presidency School of Business, Bangalore, India; [email protected] Abstract Uber, a technology company, provides a platform for customers who wish to source a taxi ride on their smart phones. This case study analyses the impact of Uberisation on supply chains and addresses the risk Uberisation entails for traditional necessitated innovations across the supply chain. firms that are unable to leverage the smartphone app technology. This development based on app technology has Keywords: Innovations, Supply Chain, Technology, Uber, Uberisation 1. Introduction 2. Literature Review Uber is a well-known taxi aggregator that is famous across The objective of this review is to trace the evolution of the globe for its path-breaking service process innova- technology based apps. tion. Uber, a technology company, provides a platform for The World Bank’s “ICT for Greater Development customers who wish to source a taxi ride on their smart Impact” strategy seeks to transform delivery of public phones. Due to digital matching of demand and supply, services, generate innovation and improve competitive- capacity utilization of the vehicle is optimum and this ness2. leads to an affordable pricing mechanism for the services. Software development has flourished along with the This creates a win-win situation for the taxi aggregator development of smart phone technology. Transportation services, customers and drivers. industry has benefited from this new smart phone app The Uber model has become so popular that it has technology. -

P2P Protocols

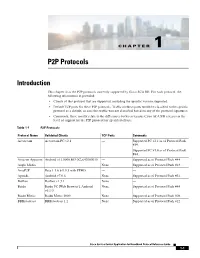

CHAPTER 1 P2P Protocols Introduction This chapter lists the P2P protocols currently supported by Cisco SCA BB. For each protocol, the following information is provided: • Clients of this protocol that are supported, including the specific version supported. • Default TCP ports for these P2P protocols. Traffic on these ports would be classified to the specific protocol as a default, in case this traffic was not classified based on any of the protocol signatures. • Comments; these mostly relate to the differences between various Cisco SCA BB releases in the level of support for the P2P protocol for specified clients. Table 1-1 P2P Protocols Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments Acestream Acestream PC v2.1 — Supported PC v2.1 as of Protocol Pack #39. Supported PC v3.0 as of Protocol Pack #44. Amazon Appstore Android v12.0000.803.0C_642000010 — Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. Angle Media — None Supported as of Protocol Pack #13. AntsP2P Beta 1.5.6 b 0.9.3 with PP#05 — — Aptoide Android v7.0.6 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #52. BaiBao BaiBao v1.3.1 None — Baidu Baidu PC [Web Browser], Android None Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. v6.1.0 Baidu Movie Baidu Movie 2000 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #08. BBBroadcast BBBroadcast 1.2 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #12. Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide 1-1 Chapter 1 P2P Protocols Introduction Table 1-1 P2P Protocols (continued) Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments BitTorrent BitTorrent v4.0.1 6881-6889, 6969 Supported Bittorrent Sync as of PP#38 Android v-1.1.37, iOS v-1.1.118 ans PC exeem v0.23 v-1.1.27. -

Collaborative Consumption: Sharing Our Way Towards Sustainability?

COLLABORATIVE CONSUMPTION: SHARING OUR WAY TOWARDS SUSTAINABILITY? by SAMUEL COUTURE-BRIÈRE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Political Science) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2014 © Samuel Couture-Brière, 2014 ABSTRACT Collaborative consumption (CC) refers to activities surrounding the sharing, swapping, or trading of goods and services within a collaborative consumption community. First, this MA thesis evaluates the factors contributing to the rapid increase of CC initiatives. These factors include technology, personal economics, environmental concerns, and social interaction. Second, the thesis explores the prospects and limits of CC in terms of sustainability. The most promising prospect is that CC seems to generate social capital and initiate a value shift away from ownership. However, institutional forces promoting growth limit this potential. The thesis concludes that CC itself is not enough to achieve sustainability, and therefore, more political solutions are needed. The paper ends with a critical discussion on the future of our growth-based economic model by suggesting that certain forms of CC could represent the roots of a “post- growth” economy. ii PREFACE This thesis is original, unpublished, independent work by the author, S. Couture-Brière. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................... -

My Children, Teaching, and Nimrod the Word

XIV Passions: My Children, Teaching, and Nimrod The word passion has most often been associated with strong sexual desire or lust. I have felt a good deal of that kind of passion in my life but I prefer not to speak of it at this moment. Instead, it is the appetite for life in a broader sense that seems to have driven most of my actions. Moreover, the former craving is focused on an individual (unless the sexual drive is indiscriminant) and depends upon that individual for a response in order to intensify or even maintain. Fixating on my first husband—sticking to him no matter what his response, not being able to say goodbye to him —almost killed me. I had to shift the focus of my sexual passion to another and another and another in order to receive the spark that would rekindle and sustain me. That could have been dangerous; I was lucky. But with the urge to create, the intense passion to “make something,” there was always another outlet, another fulfillment just within reach. My children, teaching, and Nimrod, the journal I edited for so many years, eased my hunger, provided a way to participate and delight in something always changing and growing. from The passion to give birth to and grow with my children has, I believe, been expressed in previous chapters. I loved every aspect of having children conception, to the four births, three of which I watched in a carefully placed mirror at the foot of the hospital delivery room bed: May 6, 1957, birth of Leslie Ringold; November 8, 1959, birth of John Ringold; August 2, 1961: birth of Jim Ringold; July 27, 1964: birth of Suzanne Ringold (Harman).