FGM Type IV and Other Forms of Female Genital Alterations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genital Piercings: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications for Urologists Thomas Nelius, Myrna L

Ambulatory and Office Urology Genital Piercings: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications for Urologists Thomas Nelius, Myrna L. Armstrong, Katherine Rinard, Cathy Young, LaMicha Hogan, and Elayne Angel OBJECTIVE To provide quantitative and qualitative data that will assist evidence-based decision making for men and women with genital piercings (GP) when they present to urologists in ambulatory clinics or office settings. Currently many persons with GP seek nonmedical advice. MATERIALS AND A comprehensive 35-year (1975-2010) longitudinal electronic literature search (MEDLINE, METHODS EMBASE, CINAHL, OVID) was conducted for all relevant articles discussing GP. RESULTS Authors of general body art literature tended to project many GP complications with potential statements of concern, drawing in overall piercings problems; then the information was further replicated. Few studies regarding GP clinical implications were located and more GP assumptions were noted. Only 17 cases, over 17 years, describe specific complications in the peer-reviewed literature, mainly from international sources (75%), and mostly with “Prince Albert” piercings (65%). Three cross-sectional studies provided further self-reported data. CONCLUSION Persons with GP still remain a hidden variable so no baseline figures assess the overall GP picture, but this review did gather more evidence about GP wearers and should stimulate further research, rather than collectively projecting general body piercing information onto those with GP. With an increase in GP, urologists need to know the specific differences, medical implica- tions, significant short- and long-term health risks, and patients concerns to treat and counsel patients in a culturally sensitive manner. Targeted educational strategies should be developed. Considering the amount of body modification, including GP, better legislation for public safety is overdue. -

Download the .Pdf File to Keep

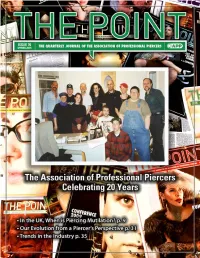

THE POINT THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSIONAL PIERCERS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Brian Skellie—President Cody Vaughn—Vice-President Bethra Szumski—Secretary Paul King—Treasurer Christopher Glunt—Medical Liaison Ash Misako—Outreach Coordinator Miro Hernandez—Public Relations Director Steve Joyner—Legislation Liaison Jef Saunders—Membership Liaison ADMINISTRATOR Caitlin McDiarmid EDITORIAL STAFF Managing Editor of Design & Layout—Jim Ward Managing Editor of Content & Archives—Kendra Jane Berndt Managing Editor of Content & Statistics—Marina Pecorino Contributing Editor—Elayne Angel ADVERTISING [email protected] Front Cover: Back issues of The Point with a photo of the original APP founders. Their identities appear on page 20. ASSOCIATION OF PROFESSIONAL PIERCERS 1.888.888.1APP • safepiercing.org • [email protected] Donations to The Point are always appreciated. The Association of Professional Piercers is a California-based, interna- tional non-profit organization dedicated to the dissemination of vital health and safety information about body piercing to piercers, health care professionals, legislators, and the general public. Material submitted for publication is subject to editing. Submissions should be sent via email to [email protected]. The Point is not responsible for claims made by our advertisers. However, we reserve the right to reject advertising that is unsuitable for our publication. THE POINT ISSUE 70 3 FROM THE EDITORS INSIDE THIS ISSUE JIM WARD KENDRA BERNDT PRESIDENT’S CORNER–6 MARINA PECORINO The Point Editors IN THE UK, WHEN IS PIERCING MUTILATION?–9 Thank You Kim Zapata! THE APP BODY PIERCING ARCHIVE–17 n behalf of the Board, the readership, and the new editorial team we would like to sincerely thank Kimberly Zapata. -

Online Piercing Studio Directory Studio Details for the Online Directory

Unit B2 · Phoenix Industrial Estate Rosslyn Crescent · Harrow · United Kingdom · HA1 2SP Tel: 020 8424 9000 · Fax: 020 8424 9000 Email: [email protected] Online Piercing Studio Directory We are creating an online directory of Body Piercing Studios is the UK. This will act as a resource for our visitors to find piercing studios around the country. We would like to list your studio in our directory and need some initial details about your studio to make an entry in our database. Once we have created an entry you will be able to update it yourself online or alternatively you can always contact us to assist you. We hope this service will be of great benefit to the piercing community and welcome your feedback and suggestions. Please complete this form and fax to 020 8424 9000. Studio Details for the Online Directory * Studio Name Contact Name Telephone Number * Email Address Website Address A link to your studio website will be shown once you have placed a link to the BodyJewelleryShop.com piercing directory. * Studio Address Post Code * Country Piercing Services gfedc Children's Piercing (Requires Consent) gfedc Body Piercing gfedc Female Piercers gfedc Earlobe and Cartilage Piercing gfedc Male Genital Piercing gfedc Piercing Scalpelling gfedc Facial and Oral Piercing gfedc Female Genital Piercing gfedc Unusual Piercing Other Services gfedc Tattooing gfedc Tattoo Removal gfedc Retail Outlet gfedc Tools/Equipment for Sale gfedc Temporary Tattoos gfedc Scarification gfedc Branding gfedc Custom Jewellery gfedc Cosmetic Tattoo Makeup gfedc Implants gfedc Suspension Studio Description Studio Description Opening Times Age Restrictions and ID Requirements. -

Piercing Aftercare

NO KA OI TIKI TATTOO. & BODY PIERCING. PIERCING AFTERCARE 610. South 4TH St. Philadelphia, PA 19147 267.321.0357 www.nokaoitikitattoo.com Aftercare has changed over the years. These days we only suggest saline solution for aftercare or sea salt water soaks. There are several pre mixed medical grade wound care solutions you can buy, such as H2Ocean or Blairex Wound Wash Saline. You should avoid eye care saline,due to the preservatives and additives it contains. You can also make your own solution with non-iodized sea salt (or kosher salt) and distilled water. Take ¼ teaspoon of sea salt and mix it with 8 oz of warm distilled water and you have your saline. You can also mix it in large quantities using ¼ cup of sea salt mixed with 1 gallon of distilled water. You must make sure to use distilled water, as it is the cleanest water you can get. You must also measure the proportions of salt to water. DO NOT GUESS! How to clean your piercing Solutions you should NOT use If using a premixed spray, take a Anti-bacterial liquid soaps: Soaps clean q-tip saturated with the saline like Dial, Lever, and Softsoap are all and gently scrub one side of the based on an ingredient called triclosan. piercing, making sure to remove any Triclosan has been overused to the point discharge from the jewelry and the that many bacteria and germs have edges of the piercing. Repeat the become resistant to it, meaning that process for the other side of the these soaps do not kill as many germs piercing using a fresh q-tip. -

Genital Piercing

Genital piercing (male) aftercare Key Advice Hand washing Do not use antibacterial products as Hand washing is the single most important they can kill the good bacteria that are The aftercare of body piercing method of reducing infection. Hands naturally present. is important to promote good must be washed prior to touching the Do not swim for the first 24 hours healing and prevent the risk of affected area, therefore reducing the risk of infection. following a piercing. infection. Wash your hands in warm water and liquid Do not pick at any discharge and do Healing times for piercing will soap, always dry your hands thoroughly not move, twist or turn the piercing vary with the type and position with a clean towel or paper towel. This whilst dry. If any secreted discharge has of the piercing and vary from should remove most germs and prevent hardened then turning jewellery may them being transferred to the affected area. cause the discharge to tear the piercing, person to person. allowing bacteria to enter the wound and A new piercing can be tender, itchy and prolonging the healing time. For the first few weeks it is slightly red and can remain so for a normal for the area to be red, few weeks. A pale, odourless fluid may Refrain from any type of sexual activity tender and swollen. sometimes discharge from the piercing and until the piercing has healed or is ‘dry’. form a crust. This should not be confused Always use barrier protection such as The healing time for a with pus, which would indicate infection. -

Comparison of Guidelines and Regulatory Frameworks for Personal Services Establishments

Comparison of Guidelines and Regulatory Frameworks for Personal Services Establishments Author: Karen Rideout Personal services establishments (PSEs) have been identified as a priority area by public health inspectors (PHIs) and provincial ministry staff in several provinces, as well as by people within the industry. There are a lot of gaps and conflicting information regarding public health issues associated with PSEs. Guidelines and regulations are often vague or impractical. In general, there is a lack of training and licensing of both practitioners and business owners within the personal services industry. The level of public health guidance for PSEs varies across jurisdictions within Canada and other countries. While guidelines for more common procedures such as aesthetics, tattooing, and body piercing vary in comprehensiveness, there is a general lack of guidance relating to more extreme forms of body modification. Because the personal services industry is constantly changing, it may be prudent to develop risk assessment procedures for infection prevention and control (IPAC) in these settings, as well as tools to assess risk from failure of IPAC procedures in any personal services setting. As invasive body modification grows in popularity and range of procedures, there is an increasing need to clarify when a procedure falls under the auspices of invasive surgery and whether it should be regulated as such. What follows is a summary of the regulatory frameworks, as well as highlights and gaps from existing guidelines/regulations, from select jurisdictions within and outside Canada. It is important to note that this is not an exhaustive summary of the guidelines; it highlights some key areas that may be particularly relevant, problematic, or those that vary most between jurisdictions. -

Genital Piercing Aftercare

Cleaning your new piercing During healing Before you do anything: WASH YOUR HANDS!!! You should never handle a fresh piercing Make sure to change your underwear daily and to with dirty hands. bathe regularly. Either a gentle, unscented baby soap or saline [store bought or homemade] can be used to clean Some people may experience bleeding during the your piercing. first couple of days, especially during arousal. For people with a vulva a saline is often Wearing a pantyliner or menstrual pad to absorb preferred as even the gentlest of soaps can irritate the blood and keep your clothes from becoming delicate tissue. stained can be a good idea for some. To clean the piercing, first soak the piercing in warm water to help soften any dried lymph that Depending on your anatomy and where your may be on the jewellery and then gently clean with piercing sits, you may want to avoid tight pants, either clean fingers or a wet q-tip. Rinse well and bicycles, stairs, or anything that causes excessive gently dry [either air-dry, paper towel, or hairdryer movement or pressure in the pelvic region. It’s set to cold] always best to go slow and listen to your body for what you can and can’t do. Saline [salt] Soaks Genital Piercings and sex Home-made saline (salt water) is only effective when the correct amount of salt is added. If you While your piercing is healing it is not necessary to would like the convenience, a sterile, isotonic abstain from sexual contact, but the longer you can saline solution [0.9% NaCl] can be purchased at hold off the better [this includes masturbation]. -

Aftercare Guide

AFTERCARE GUIDE 1624 64111 . • (816) 561-1802 he following is a collection of aftercare suggestions to help you to heal your new piercing. Everyone heals di erently, some faster, some slower. Be patient, listen to your body, follow these instructions and you and your piercing will have a long, happy life together. If you ever have any questions or concerns please contact us, we are more than happy to help you. DO NOT --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Do not use alcohol, peroxide, anti-bacterial gels/creams, Bactine® or witch hazel. All of these are not to be used on puncture wounds, your piercing is a puncture wound. Do not move, twist, rotate or turn your jewelry while it is healing. Your body will heal and adapt to your piercing much faster if you leave it alone. Do not let anyone touch your piercing or come in oral contact with your piercing. This includes children, pets, loved ones and curious people in general. Do not apply makeup, face creams or lotions to the immediate area of your piercing. Do not remove your jewelry to clean the piercing. It may close quickly without jewelry in the piercing. If you like your piercing always have jewelry in it. Do not pick at your piercing with your finger nails or scrub at it with a cotton swab. WHAT TO EXPECT DURING HEALING --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Swelling, bleeding and bruising is normal for a fresh piercing and can occur and reoccur for the first week or more. Soreness and redness is normal and can be expected if the piercing is bumped or pulled (snagged on your clothing, sleeping on it, etc). -

Complications Associated with Intimate Body Piercings

UC Davis Dermatology Online Journal Title Complications associated with intimate body piercings Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5gp333zr Journal Dermatology Online Journal, 24(7) Authors Lee, Brigette Vangipuram, Ramya Petersen, Erik et al. Publication Date 2018 DOI 10.5070/D3247040908 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Volume 24 Number 7| July 2018| Dermatology Online Journal || Review 24(7): 2 Complications associated with intimate body piercings Brigette Lee1 BS, Ramya Vangipuram2,3 MD, Erik Peterson3 MD, Stephen K Tyring2,3 MD PhD Affiliations: 1Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA, 2Center for Clinical Studies, Webster, Texas, 3Department of Dermatology, McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, Texas Corresponding Author: Brigette Lee, 1 Baylor Plaza, Houston, Texas 77030, Tel: 210-912-7885, Fax: 281-335-4605, Email: [email protected] years in places such as Cambodia, India, and Abstract Intimate body piercings involving the nipple and religious texts dating back to 1500 Before Common genitalia have increased in prevalence in both men Era (BCE), describe the goddess Lakshmi wearing and women. Despite this increase, there is a earlobe and nose piercings [2]. The Romans deficiency in the literature regarding the short and practiced infibulation by passing a ring through the long-term complications of body piercings, including prepuce of males, an early form of genital piercing, an increased risk of infection, malignancy, and although the purpose was to inhibit sexual structural damage to the associated tissue. Breast abscesses associated with nipple piercing can be excitement [1, 2]. -

Genital Male Piercings Mircea Tampa Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Tampa [email protected]

Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 3 2015 Genital Male Piercings Mircea Tampa Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, [email protected] Maria Isabela Sarbu Victor Babes Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, [email protected] Alexandra Limbau Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Monica Costescu Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Vasile Benea Victor Babes Hospital of Infectious and Tropical Diseases See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Tampa, Mircea; Sarbu, Maria Isabela; Limbau, Alexandra; Costescu, Monica; Benea, Vasile; and Georgescu, Simona Roxana (2015) "Genital Male Piercings," Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms/vol2/iss1/3 This Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Genital Male Piercings Authors Mircea Tampa, Maria Isabela Sarbu, Alexandra Limbau, Monica Costescu, Vasile Benea, and Simona Roxana Georgescu This review article is available in Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jmms/vol2/iss1/3 JMMS 2015, 2(1): 9- 17. Review Genital male piercings Mircea Tampa1, Maria Isabela Sarbu2, Alexandra Limbau3, Monica Costescu1, Vasile Benea2, Simona Roxana Georgescu1 1 Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Dermatology 2 Victor Babes Hospital for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Bucharest, Romania 3 Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Department of Microbiology Corresponding author: Mircea Tampa, e-mail: [email protected] Running title: Genital male piercings Keywords: genital piercings, sexual enhancement, infibulation www.jmms.ro 2015, Vol. -

Painful Pleasures Piercing Glossary

Painful Pleasures Piercing Glossary Whether you're an experienced piercer or someone just beginning to explore the world of body piercings and other body modifications, you're sure to learn something new by reading this piercing glossary. It's filled with common piercing terminology and definitions ranging from explanations of what different piercing tools are used for to piercing safety terms to types of body piercings, where they're placed and what types of body jewelry work best in them, and beyond. We've also included a few definitions related to extreme body modifications that some piercers perform, like scarification, branding and human suspension. If you ever read a word in one of our Information Center articles or piercing blog posts that's unfamiliar to you, pop on over to this piercing glossary to expand your piercing knowledge by looking up a specific piercing phrase and its definition. Just click a piercing term below to see its definition or read straight through the Basic Piercing Terminology and Types of Piercings sections in this glossary for a fairly thorough education on piercing terminology. Definitions are sorted alphabetically to make it easy to find a specific term when you want to look up just one piercing definition. When definitions include other terms from this piercing glossary, you can click an unfamiliar phrase to jump to its definition, too. Other links within this glossary will take you to actual products so you can see the body jewelry, piercing tools and other piercing supplies being referenced and shop for those items, as desired. Note: Some definitions have "learn more" links following them. -

Genital Piercing (Female) Aftercare Key Advice Hand Washing Do Not Swim for the First 24 Hours Hand Washing Is the Single Most Following a Piercing

Genital piercing (female) aftercare Key Advice Hand washing Do not swim for the first 24 hours Hand washing is the single most following a piercing. The aftercare of body piercing important method of reducing infection. Do not pick at any discharge and do is important to promote good Hands must be washed prior to touching not move, twist or turn the piercing the affected area, therefore reducing the healing and prevent the risk of whilst dry. If any secreted discharge has risk of infection. infection. hardened then turning jewellery may cause the discharge to tear the piercing, Healing times for piercing will Wash your hands in warm water and liquid soap, always dry your hands allowing bacteria to enter the wound and vary with the type and position thoroughly with a clean towel or paper prolonging the healing time. of the piercing and vary from towel. This should remove most germs Refrain from any type of sexual activity and prevent them being transferred to person to person. until the piercing has healed or is ‘dry’. the affected area. For the first few weeks it is Always use barrier protection such as A new piercing can be tender, itchy and condoms, otherwise you are at increased normal for the area to be red, slightly red and can remain so for a risk of acquiring a sexually transmitted tender and swollen. few weeks. A pale, odourless fluid may infection. sometimes discharge from the piercing The healing time for a and form a crust. This should not be Signs of infection genital piercing can be from confused with pus, which would indicate If appropriate aftercare is not followed infection.