Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Executive Power Ofthe Commonwealth: Its Scope and Limits

DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY Parliamentary Research Service The Executive Power ofthe Commonwealth: its scope and limits Research Paper No. 28 1995-96 ~ J. :tJ. /"7-t ., ..... ;'. --rr:-~l. fii _ -!":u... .. ..r:-::-:_-J-:---~~~-:' :-]~llii iiim;r~.? -:;qI~Z'~i1:'l ISBN 1321-1579 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1996 Except to the extent of the uses pennitted under the Copyright Act J968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any fonn or by any means including infonnation storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using infonnation publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Parliamentary Research Service (PRS). Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. PRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members ofthe public. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1996 Parliamentary Research Service The Executive Power ofthe Commonwealth: its scope and limits Dr Max Spry Law and Public Administration Group 20 May 1996 Research Paper No. 28 1995-96 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the help given by Bob Bennett, the Director of the Law and Public Administration Group. -

Autumn 2015 Newsletter

WELCOME Welcome to the CHAPTER III Autumn 2015 Newsletter. This interactive PDF allows you to access information SECTION NEWS easily, search for a specific item or go directly to another page, section or website. If you choose to print this pdf be sure to select ‘Fit to A4’. III PROFILE LINKS IN THIS PDF GUIDE TO BUTTONS HIGH Words and numbers that are underlined are COURT & FEDERAL Go to main contents page dynamic links – clicking on them will take you COURTS NEWS to further information within the document or to a web page (opens in a new window). Go to previous page SIDE TABS AAT NEWS Clicking on one of the tabs at the side of the Go to next page page takes you to the start of that section. NNTT NEWS CONTENTS Welcome from the Chair 2 Feature Article One: No Reliance FEATURE Necessary for Shareholder Class ARTICLE ONE Section News 3 Actions? 12 Section activities and initiatives Feature Article Two: Former employees’ Profile 5 entitlement to incapacity payments under the Safety, Rehabilitation and FEATURE Law Council of Australia / Federal Compensation Act 1988 (Cth) 14 ARTICLE TWO Court of Australia Case Management Handbook Feature Article Three: Contract-based claims under the Fair Work Act post High Court of Australia News 8 Barker 22 Practice Direction No 1 of 2015 FEATURE Case Notes: 28 ARTICLE THREE Judicial appointments and retirements Independent Commission against High Court Public Lecture 2015 Corruption v Margaret Cunneen & Ors [2015] HCA 14 CHAPTER Appointments Australian Communications and Media Selection of Judicial speeches -

The State of the Australian Judicature

The 36th Australian Legal Convention The State of the Australian Judicature Chief Justice RS French 18 September 2009, Perth In his State of the Judicature address to this Convention in 2007 the former Chief Justice, Murray Gleeson, observed, not without pleasurable anticipation: Few things in life are certain, but one is that I will not be giving the next such address. And so it came to pass. In quoting my predecessor, I would like to acknowledge his lifelong contribution and commitment to the rule of law and particularly his decade as Chief Justice of Australia. Assuming my continuing existence and that of the Australian Legal Convention, I expect to deliver three more such addresses as Chief Justice. It will be interesting on the occasion of the last of them to reflect on change in the legal landscape which will have come to pass then but still lies ahead of us today. For there has been much change since the first of these addresses. And prominent among life's few certainties is more of it. 2 The State of the Australian Judicature address given at the Australian legal Convention is a task that each Chief Justice has accepted beginning with Sir Garfield Barwick in Sydney in July 1977. In his opening remarks he said he had agreed to give the address because, as he put it1: … it seems to me that Australia is slowly developing a sense of unity in the administration of the law, as it is to be hoped it is developing a sense of unity in the legal profession. -

Rules of Appellate Advocacy: an Australian Perspective

RULES OF APPELLATE ADVOCACY: AN AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE Michael Kirby AC CMG* I. ADVOCACY AND AUSTRALIAN COURTS Australia is a common law federation. Its constitution,' originally enacted as an annex to a statute of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, was profoundly affected-so far as the judiciary was concerned-by the model presented to the framers by the Constitution of the United States of America.2 The federal polity is called the Commonwealth, a word with links to Cromwell and American revolutionaries, a word to which Queen Victoria was said to have initially objected. The colonists were insistent; Commonwealth it became. The sub-national regions of the Commonwealth are the States. There are also territories, both internal3 and external,4 in respect of which, under the Constitution, the federal Parliament enjoys plenary law-making power. In the internal territories and the territory of Norfolk Island, a high measure of self-government has been granted by federal legislation. When the Commonwealth of Australia was established there were already courts operating in each of the colonies that united in the federation. They became the state courts. Generally * Justice of the High Court of Australia. Formerly President of the Courts of Appeal of New South Wales and of Solomon Islands and Judge of the Federal Court of Australia. 1. AUSTL. CONST. (Constitution Act, 1900, 63 & 64 Vict., ch. 12 (Eng.)). 2. Sir Owen Dixon, Chief Justice of Australia (1952-64), observed that the framers of the Australian constitution "could not escape" from the fascination of the United States model. Cf. The Queen v. -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

The Accountability of the Courts Year 12 Teacher Resource

Francis Burt Law Education Programme THE ACCOUNTABILITY OF THE COURTS YEAR 12 TEACHER RESOURCE This resource addresses the following Year 12 Stage 3 Politics and Law syllabus item: 3B: The accountability of the courts through the appeals process through parliamentary scrutiny and legislation through transparent processes and public confidence through the censure and removal of judges Part A: Introduction, Appeals and Legislation Possible Preliminary Discussion Points a) Discuss what the term ‘the accountability of the courts’ actually means. b) In what ways should judges be held accountable? c) What problems may occur if the accountability of the judiciary was the task of the executive arm of government? Introduction “The independence of the judiciary lies at the heart of the rule of law and hence of the administration of justice itself. The essence of judicial independence is that the judge in carrying out his judicial duties, and in particular in making judicial decisions, is subject to no other authority than the law.... In particular, the judiciary should be free from the control of the executive government or of any department or branch of it.”1 “No judge could be expected to carry out judicial tasks with impartiality if one side in the dispute had the power to dismiss that judge, move the judge out of office or reduce his or her salary or could cause its elected representatives to do so. The issue was put succinctly by Australia’s former Chief Justice, Murray Gleeson, in a Boyer Lecture in December 2000 when he declared: ‘The ultimate test of public confidence in the judiciary is whether people believe that in a contest between a citizen and government they can rely upon an Australian court to hold the scales of justice evenly.’”2 “That the purpose of judicial independence was not to provide a benefit to the judiciary but to enable the judicial system to function fairly with integrity and impartiality”3 was indicated by Western Australia’s Chief Justice, the Honourable Wayne Martin AC, at a conference in New Zealand in 2011. -

The Changing Position and Duties of Company Directors

CRITIQUE AND COMMENT THE CHANGING POSITION AND DUTIES OF COMPANY DIRECTORS T HE HON JUSTICE GEOFFREY NETTLE* In 1974, in the first edition of his Principles of Company Law, Professor Ford was able to say that directors’ duties were ‘not very demanding’. This lecture traces how the duties and standards of care demanded of company directors have increased since then. In doing so, it makes reference to the attenuated business judgment rule, comparing the positions in the United Kingdom and, briefly, South Africa. It then considers similarities and differences between the duties imposed on company directors, union officers and public officials. It suggests that, while the regulatory regimes that apply to company directors and union officers are strikingly different, there is little reason in principle why that should be so. For practical reasons, the same cannot be said of the differences between public officials and company directors or union officers. But it remains somewhat paradoxical that, although the actions of public officials may have far more broad- ranging effects on the nation’s wellbeing than the actions of any company director or union officer, public officials’ duties are much less onerous. CONTENTS I Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1403 II Directors’ Duties .................................................................................................... 1404 A The Development of Directors’ Duties in Equity ................................ -

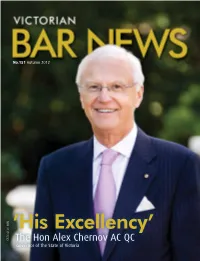

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

Alumni News2005v11.Indd

POSTCARDS AND LETTERS HONOURS DEATHS (August 2003 – July 2005) OBITUARIES Alumni News Supplement to Trinity Update August 2005 Trinity College 2004 AUSTRALIA DAY HONOURS Dr Yvonne AITKEN, AM (1930) REGINALD LESLIE STOCK, OBE, COLIN PERCIVAL JUTTNER JOHN GORDON RUSHBROOKE THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE Dr Nancy AUN (1976) 1909-2004 1910-2003 1936-2003 Hugh Wilson BALLANTYNE (1951) AC Reg Stock entered Trinity in 1929, studying for a Following in his father’s footsteps, Colin Juttner entered John Rushbrooke entered Trinity from Geelong Grammar in What a kaleidoscope of activities is reflected in this collection of news items, gathered since August 2003 from Peter BALMFORD (1946) Leonard Gordon DARLING (TC 1940), AO, CMG, combined Arts/Law degree. He was elected Secretary Trinity from St Peter’s College, Adelaide, in 1929 and 1954 with a General Exhibition. He completed his BSc in Alumni and Friends of Trinity College, the University of Melbourne. We hope this new trial format will help to Dr (William) Ronald BEETHAM, AM (1949) Melbourne, Victoria. For service to the arts through of the Fleur de Lys Club in 1932 and Senior Student enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine. He took a prominent 1956, graduating with prizes in Mathematics and Physics. rekindle memories and prompt some renewed contacts, and apologise if any details have become dated. vision, advice and philanthropy for long-term benefit Dr Garry Edward Wilbur BENNETT (1938) in 1933. As such he chaired the meeting of the Club part in student life, representing the College in cricket His Master’s degree saw him begin his work as a high to the nation. -

Judges and Retirement Ages

JUDGES AND RETIREMENT AGES ALYSIA B LACKHAM* All Commonwealth, state and territory judges in Australia are subject to mandatory retirement ages. While the 1977 referendum, which introduced judicial retirement ages for the Australian federal judiciary, commanded broad public support, this article argues that the aims of judicial retirement ages are no longer valid in a modern society. Judicial retirement ages may be causing undue expense to the public purse and depriving the judiciary of skilled adjudicators. They are also contrary to contemporary notions of age equality. Therefore, demographic change warrants a reconsideration of s 72 of the Constitution and other statutes setting judicial retirement ages. This article sets out three alternatives to the current system of judicial retirement ages. It concludes that the best option is to remove age-based limitations on judicial tenure. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 739 II Judicial Retirement Ages in Australia ................................................................... 740 A Federal Judiciary .......................................................................................... 740 B Australian States and Territories ............................................................... 745 III Criticism of Judicial Retirement Ages ................................................................... 752 A Critiques of Arguments in Favour of Retirement Ages ........................ -

2015-16 High Court of Australia Annual Report

HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2015–2016 © High Court of Australia 2016 ISSN 0728–4152 (print) ISSN 1838–2274 (on-line) This work is copyright, but the on-line version may be downloaded and reprinted free of charge. Apart from any other use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part may be reproduced by any other process without prior written permission from the High Court of Australia. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Public Information, High Court of Australia, GPO Box 6309, Kingston ACT 2604 [email protected]. Images © Adam McGrath Designed by Spectrum Graphics sg.com.au High Court of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 25 October 2016 Dear Attorney In accordance with section 47 of the High Court of Australia Act 1979 (Cth), I submit on behalf of the High Court and with its approval a report relating to the administration of the affairs of the Court under section 17 of the Act for the year ended 30 June 2016, together with financial statements in respect of the year in the form approved by the Minister for Finance. Section 47(3) of the Act requires you to cause a copy of this report to be laid before each House of Parliament within 15 sitting days of that House after its receipt by you. Yours sincerely Andrew Phelan Chief Executive and Principal Registrar of the High Court of Australia Senator the Honourable George Brandis QC Attorney-General Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 – PREAMBLE 5 PART 6 – ADMINISTRATION 31 Overview 31 -

KEYSTONE of the FEDERAL ARCH Origins of the High Court of Australia

KEYSTONE OF THE FEDERAL ARCH Origins of the High Court of Australia As the 19th century was drawing to a close the colonies of Australia were preparing to form a new nation. To lay the foundations for this emerging nation a new Constitution would need to be drafted. The delegates, who gathered, first in Melbourne, then in Sydney, to undertake the challenge of creating the Constitution also knew that a new court would be needed. As a matter of fact, the idea of an Australian appellate court had been considered as early as 1840. It was an idea which had been revisited many times before that first Federal Convention. In 1891, the delegates elected from the various States and New Zealand met in Sydney to work and to consider draft Constitutions. Presided over by Sir Henry Parkes, the grand old man of Federation, the Convention appointed a drafting committee to take the issues raised in debate and construct a blueprint for a new country, a new parliament and a new court. Some of those present – Griffith, Barton and Deakin – were to play a large part in the creation of the new court some 12 years later. Among those appointed to draft the new Constitution were the Tasmanian Attorney-General, Andrew Inglis Clark, Sir Charles Kingston, the Premier of South Australia and the Premier of Queensland, Sir Samuel Griffith. From the debates which took place, and using their knowledge of the United States and Canadian Constitutions, they produced a series of drafts which dealt with the matters thought to be necessary.